The apocryphal “Chinese” curse “May you live in interesting times” is without a doubt well suited for the present day. As I observed last week, we live in a perilously “interesting” time, a time of wealth destruction on a global scale:

Wealth is being destroyed right before our eyes. That wealth destruction is continuing, and will continue to be both brutal and ugly.

While the aforementioned curse is almost certainly not of Chinese origin, the nexus of Chinese and Western cultures in what has been documented about the saying affords an interesting backdrop for looking at the relative states of the world’s leading economies—the United States and China—and the impacts their respective central banks (the Federal Reserve and the People’s Bank of China, or PBOC) have had.

The Financial Picture Is Grim

Certainly when one looks at both US and Chinese financial markets, there is zero doubt that both the US and China are having an horrible 2022.

However, over the past month, Chinese markets have fared better than their US counterparts.

Yet if the discipline of economics teaches us anything at all, it is the dangers of narrow, short-term perspectives. Not only should we not confined ourselves to just scrutiny of the financial market indices, we should not draw too many conclusions from just the 2022 data. Current market events are always the product of prior economic forces, in every economy.

The Pandemic Era

Given the COVID-19 pandemic, plus its attendant lockdowns and global supply-chain dislocations, the beginning of 2020 presents a natural starting point for evaluating recent Chinese vs US central bank economic and monetary policies.

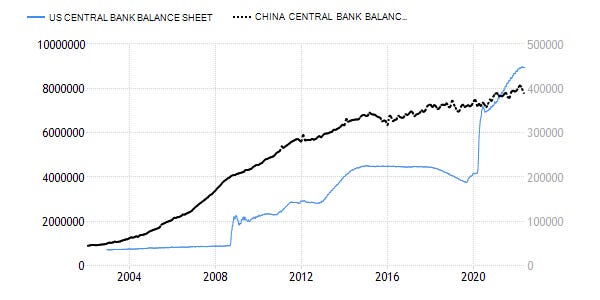

The most notable monetary event, particularly for the US, is the near doubling of the US Federal Reserve’s balance sheet in 2020, from just over $4 trillion to just under $8 trillion, with the Fed continuing to expand its balance sheet up to the present level of $8.9 trillion. Over the same period, the balance sheet for the PBOC has expanded as well, but far more chaotically, with a significantly slower long-term growth trend.

Of particular note, the PBOC balance sheet has declined sharply in recent months, while the Fed’s balance sheet has continued to creep upwards (meaning the Fed has not “yet” tightened monetary policy).

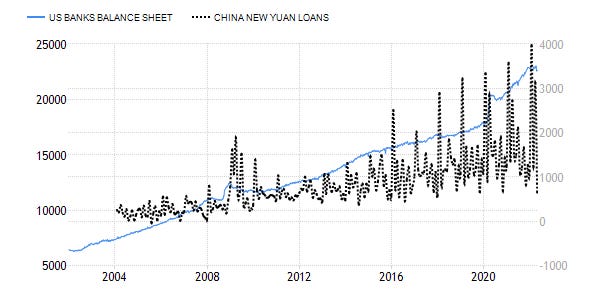

What is the impact of a central bank’s balance sheet? While ultimately such measures influence the overall money supply, a far more immediate effect appears when one looks at the state of private borrowing and debt creation. The Fed’s willingness to dramatically expand its balance sheet in 2020 was matched by expansions of loans and overall private debt.

The argument for promoting loans to the private sector is that such loans represent expansions of economic activity. However, even if one assumes this to be the case, one must also concede that such stimulative effect from the Fed’s own balance sheet expansions was strictly temporary, as US private loans rose sharply in 2020 and then trended down throughout the remainder of that year and most of 2021, before starting to trend up again in the latter half of the year.

Interestingly, the more chaotic pattern of balance sheet expansion by the PBOC has not produced a similar stimulative effect on private sector loans, as the trend throughout 2020 and 2021, accounting for China’s much greater volatility, is largely horizontal (meaning little or no growth), and the trend in 2022 is down.

The net effect of these patterns, however, puts China’s private sector loans in a better position than the US during the last half of 2021, where the relative levels clearly favor China. Only in recent months has the situation reversed, as China’s private sector loans have nosedived.

A similar pattern for the US plays out when examining US bank balance sheets in aggregate (bank balance sheets are a proxy for total levels of debt and credit in an economy). The 2020 Fed expansion resulted in a similar expansion of US bank balance sheets, again indicating an expansion of business and commercial activity. Notably for China, over the same time frame bank balance sheets have actually shrunk.

Also of note, bank balance sheets in China have decline sharply during the first part of 2022, while their US counterparts have more or less held steady.

A final comparison between China and the US is to consider the performance of the US dollar vs the Chinese yuan since the start of 2020. Whatever else might be concluded from US and Chinese private sector loan growth and bank balance sheet expansions, one thing is certain: the yuan strengthened against the dollar throughout the latter portion of 2020 and nearly all of 2021, only to reverse and weaken in 2022.

The drop in the value of the yuan correlates to a decline in the PBOC central bank balance sheet, Chinese bank balance sheets overall, as well as private sector loans.

Overall, an argument can be made that, while bank balance sheet growth was higher in the US than in China, the net impact of the central bank balance sheet has been more favorable to China than to the US up until the past few months, when the situation has sharply reversed—a shift that is not likely to be healthy for China’s economy overall.

The Historical Pattern

Yet if central bank balance sheet growth has favored China through most of the Pandemic Era, a period when central bank balance sheet growth was actually greater in the US, the longer historical view paints a dramatically different picture.

If we pull back to a twenty-year timespan, looking from the start of 2002 to the present day, one thing immediately is clear: The PBOC’s balance sheet has greatly outpaced the Federal Reserve’s right up until the start of the Pandemic Era.

The Pandemic Era effects on private sector loans and overall bank balance sheets are seen on the historical scale, but similarly reversed.

Overall, private sector loan growth has trended higher in the US than in China since 2002, and in particular since around 2010 (the aftermath of the 2008 Great Financial Crisis).

The same is true for bank balance sheets in general.

If a sustained growth in private sector loans and bank balance sheets is indicative of sustained expansion of business investment and business activity, the historical trend is quite clear: the US has outperformed China. That alone makes a compelling case that the US economy, for all its faults, flaws, and problems, is in better shape than its Chinese counterpart.

Interventions Fail

Yet there is an interesting object lesson to be derived here: Expanding the central bank balance sheet is not all that helpful in either the short or the long term. When the PBOC had less balance sheet growth than the Fed, expansionary loan growth favored China. When the Fed had less balance sheet growth than China, expansionary loan growth favored the US.

Far from stimulating the US economy, the Fed’s interventionist policies and willingness to expand its balance sheet arguably has had the reverse effect, and has hindered rather than encouraged business and economic growth.

Likewise, the PBOC’s willingness to put its thumb on the economic scale has not helped China’s economy.

Paradoxically, if there is indeed a causal relationship between the PBOC’s balance sheet contraction, private sector loan contraction, and bank balance sheet contraction in China, as well as with the decline of the yuan, a similarly deleterious impact might potentially ensue from a central bank reducing its balance sheet. While this is admittedly counterintuitive, the unavoidable reality of a central bank reducing its balance sheet is that the reduction is just as interventionist as the expansion—and the fatal flaw of such policies is that any intervention by a central bank in the economy is inherently counterproductive.

In other words, neither the Federal Reserve nor the PBOC have any way to shrink their balance sheets without negatively impacting their respective economies, and both central banks are effectively hoist by their own petard. No matter which way either institution turns, their next moves are almost sure to have significant negative consequences.

Both the Federal Reserve and the People’s Bank of China have failed in their fundamental mission of shepherding the national economy for their respective countries. The relevant question going forward is going to be which central bank has failed the most and done the greatest damage.

These are definitely “interesting times”!

I'm no economist, unfortunately, neither is anyone at either of these two central banks.

I have a saying, "The Chinese didn't invent 'bathtub manufacture' but they may have perfected it."

I suspect the same is true about 'Wealth Destruction.'