Beijing Panics, Loads Stimulus Cannon

Clearest Signal Yet That "Recovery" Just Is Not Happening

China is getting desperate to engineer some sort of economic “recovery”, and it is reaching the stage of not caring much about how that gets done or what the knock-on effects will be. With a moribund economy and multiple debt crises unfolding even as I write this, China is rapidly running out of maneuvering room. If it is going to generate economic growth on part with its prior track record, it needs something to begin happening and soon.

The first sign of the growing desperation came two weeks ago when the National Administration of Financial Regulation began urging banks to loosen lending practices, in particular to goose purchases of durable goods such as cars.

The National Administration of Financial Regulation in a notice told lenders to relax application conditions for auto loans, lower down payments and extend loan terms to make cars more affordable. It urged lenders to simplify auto loan applications by promoting instant online processing. The regulator specifically called for increasing financing support for used cars to encourage consumers to upgrade their autos.

To bolster support for new-energy vehicles, it is necessary to develop and design exclusive financial products and services that meet the characteristics of the vehicles, the notice says. Lenders should also provide credit support to the construction of electric vehicle charging infrastructure in rural areas.

China is feeling pressure to take such steps because Chinese consumers just aren’t consuming. Households lack confidence in the future path of the economy as well as significant purchasing power to direct towards consumption.

At the same time, China’s local governments are facing an increasing amount of pressure servicing their debts.

As such, some local governments are facing increasing debt-repayment pressure after years of hefty spending on low-return infrastructure projects. The Politburo, the centre of power within the Communist Party, said in July that there would be a “comprehensive” plan to resolve local government debt risks, but no details of the debt-resolution plan have been officially announced.

A number of policy advisers to Beijing have been urging the central government to bail out indebted local governments, pointing to how a prolonged property market downturn could further weaken finances at local governments, which play a critical role in supporting the national economy.

With two of the largest private real estate developers, Evergrande and Country Garden, locked in a death spiral down into liquidation, not only have housing markets collapsed, but developers are not buying land from local government entities as in the past—thereby depriving those same local governments of a much needed revenue stream at a time when they have outsized debt loads to service.

No local government or local government financing vehicle (LGFV) has defaulted on a debt issuance…yet. However, absent major debt relief from some direction, it is likely only a matter of time before defaults happen.

Consequently, last week Xi Jinping began to load the stimulus cannon, preparing to resort to debt-financed stimulus spending to lift the economy out its seemingly perpetual doldrums.

President Xi Jinping signaled that a sharp slowdown in growth and lingering deflationary risks won’t be tolerated, making a series of rare policy moves to boost sentiment in the world’s second largest-economy.

Within a 24-hour window on Tuesday, China increased its headline government deficit to the largest in three decades, unveiled a sovereign debt package that marked a shift from its traditional growth model, and Xi made an unprecedented trip to the central bank — sending a powerful message about his focus on the economy.

The message Xi Jinping is sending can be summed up in one word: Panic!

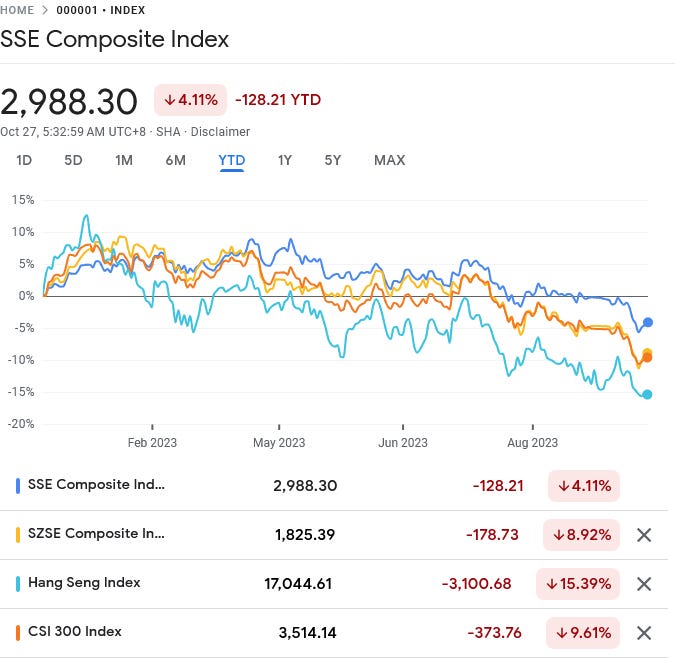

China’s economy is not firing well on any cylinder at the moment. Year to date all major stock indices are down significantly, with Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index deep into correction territory (down more than 10%).

At the same time, yuan loan growth printed at the lowest level in over a year.

Outstanding yuan loans in China rose 10.9% from a year earlier in September 2023, the least since April 2022 and missing market expectations of 11.1% growth. source: People's Bank of China

The lack of loan activity is having an unexpected consequence: money supply growth is constrained.

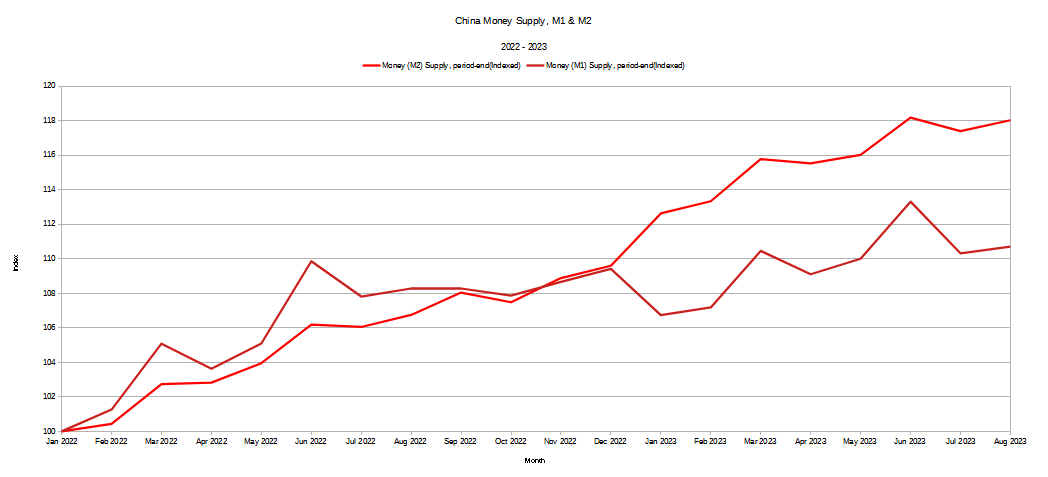

Beijing’s monetary policy has always been fairly loose, with steady growth of the M2 Money Supply stretching back several years.

However, as can be seen when the data is indexed to January of 2022, both the M1 and M2 Money Supply have plateaued somewhat in recent months.

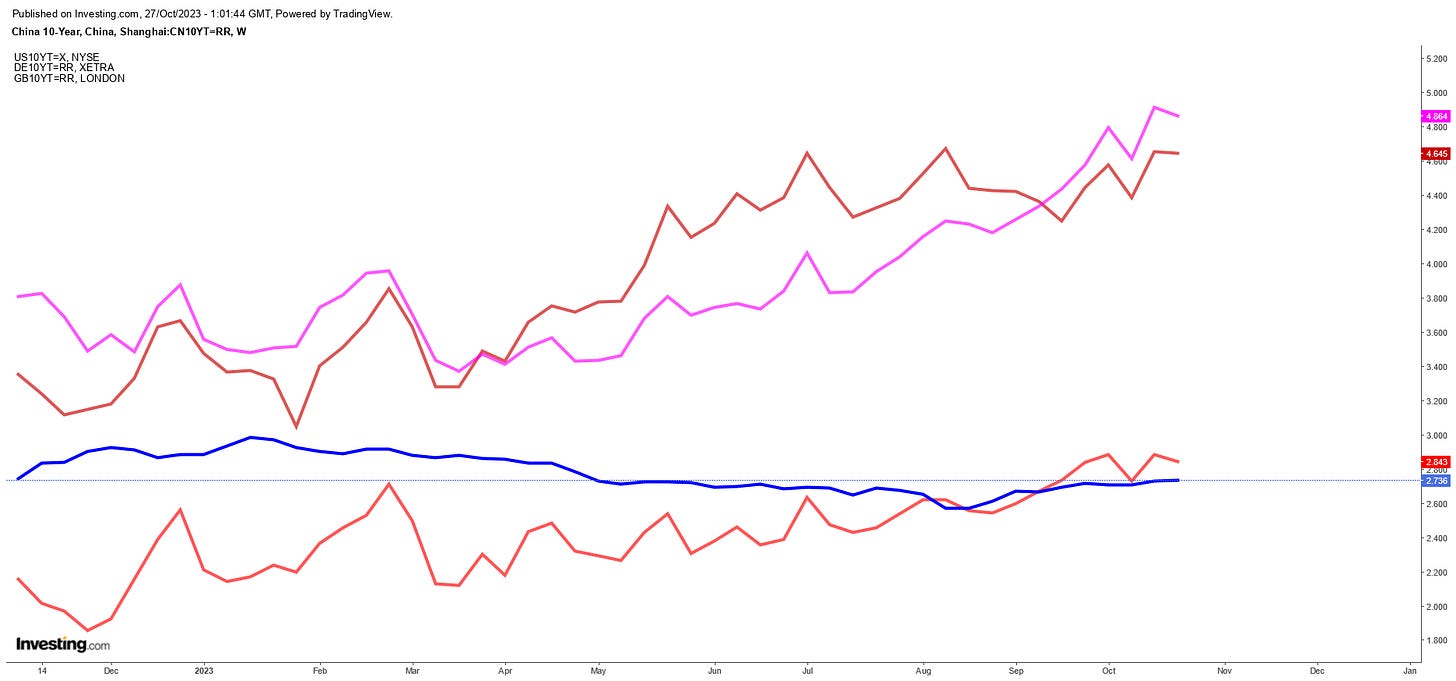

In the bizarro world of government stimulus, a constrained money supply makes the use of stimulus that much more difficult. While China is not facing the same rising yields that have become the norm in Europe and here in the US, declining yields are limiting the degree to which stimulus lending can lead to either increased investment or increased consumption.

China’s sovereign debt yields have even declined in recent months.

On the one hand, China’s relatively low debt yields minimizes the consequence to Beijing of additional stimulus lending—which may have played a role in Beijing’s decision to authorize an additional 1 trillion yuan in sovereign debt issuance.

Within a 24-hour window on Tuesday, China increased its headline government deficit to the largest in three decades, unveiled a sovereign debt package that marked a shift from its traditional growth model, and Xi made an unprecedented trip to the central bank — sending a powerful message about his focus on the economy.

The one-trillion-yuan budget boost and willingness to exceed a long-adhered to 3% debt-to-GDP limit displayed a determination by Beijing to shore up growth for 2024 and avoid complacency. That comes even after strong economic data published this month put the government on target for its 5% goal this year. China will next week hold a twice-a-decade financial policy gathering that may provide more policy clarity.

On the other hand, low yields in the offshore debt markets makes other nations’ sovereign debt issuances more attractive to investors, which has not helped alleviate China’s ongoing capital outflow.

It is difficult if not impossible to generate significant economic growth when investment capital is leaving the country—and investment capital has been fleeing China since the right after the start of the COVID-19 Pandemic Panic.

This creates additional headaches for Beijing, as China’s debt is already at eyewatering levels.

China’s debt-to-GDP ratio rose to a record in the second quarter, and concern is mounting over borrowing by local governments and their financing platforms. “Because Chinese debt is high already, totaling roughly 280% of GDP, so we cannot bring a huge, oversized generous stimulus,” Zhu said in the BTV interview.

Despite this, the People’s Bank of China has been steadily expanding its balance sheet since the pandemic—and is now planning to expand it even more.

China needs to unleash a significant blast of debt-financed stimulus in order to get the economy growing again, but lacks the headroom for an unlimited amount of debt.

China’s position is further exacerbated by its steadily weakening currency, which has been losing ground against the dollar since the beginning of the year.

With additional soveriegn debt on the way, Beijing will have its work cut out for it if it wants to keep the yuan below 7.5 yuan to the dollar—which would be a decline of more than 11% year to date.

Even Russia’s ruble has been gaining ground on the yuan over the past month.

This is coming at a time when the ruble has lost 42% of its value against the dollar.

China isn’t even gaining any benefit in improved exports from its depreciating currency.

As a general rule, a weaker currency makes a country’s exports more attractive to importing nations. However, as China’s yuan has weakened offshore, exports have by and large declined.

The weaker currency certainly has not helped its domestic consumption patterns either, which are still lagging prior years’ activity.

Flagging export demand and sluggish domestic demand equates to an economy stuck somewhere between deflation and stagflation, which is exactly where China’s economy has been stuck for quite a while now.

As much as China strives to keep the brave face about its economic situation, the reality is that China is increasingly stuck between a deflationary rock and an inflationary hard place. It cannot unleash dramatic amounts of sovereign debt-financed stimulus spending, even currency devaluation has failed to stimulate export demand, and Chinese consumer stubbornly refuse to consume.

While the overall impact of still more debt-financed stimulus remains to be assessed, at the levels Beijing is preparing to roll it out, it is not likely that Beijing will greatly alter the economy’s overall trajectory. This may prove to be a blessing in disguise, as it means that China may manage to avoid creating yet another asset bubble while attempting to boost its economy.

Xi Jinping did not want to go the sovereign debt-financed stimulus route. Since 2020 and his now-infamous “Three Red Lines,” Xi Jinping has tried to utilize almost every other mechanism for getting more capital and more spending into the economy—two prerequisites if there is to be any economic growth of any kind. None of them have worked.

Now Xi is choosing to give the old economic playbook a second chance. Beijing will issue 1 Trillion yuan in sovereign debt and hope that the resulting spending will lift China’s economy off the rocky shoals against which it has been flung repeatedly.

Will that 1 Trillion yuan be enough? Can China get the necessary economic boost from the related spending? If—or perhaps when—the stimulus spending fails to lift the economy, what does Beijing do then?

Beijing is running out options for getting its economy moving again. No wonder Xi is panicking.

Will it be, as Celente says, when all else fails, they take you to war? Or is the East different? Certainly Celente's dictum applied to Tojo's Japans in the 1930s so maybe this is a universal thing....

Three questions:

1) Does the Chinese data you’re analyzing break down by region or even by city? I ask because if there are huge differences in financial troubles between the different local governments (and their LGFVs) then socialism might require the more financially stable regions to bailout the ones in trouble. If so, resentment might build in the cannibalized regions enough to lead to a future political instability and maybe even revolt. On the other hand, if all regions have pretty much the same financial problems, then future revolt would likely have to come about through a different pathway.

2) Xi says deflationary results will not be ‘tolerated’. Does he actually have any mechanisms that would prevent this, without creating a new asset bubble, or draconian political measures?

3) You have previously written that deflationary problems in China would lead to some financial contagion in the USA. Do you still see that, and do you see it now being likely more severe, given the real estate and banking problems we currently have?

Thanks, Mr. Kust!