With America’s quadrennial soap opera known as the Presidential election now in full swing, we need to establish an important context for framing the various policy promises and prognostications being made by both Kamala Harris and Donald Trump.

It helps that the Federal Reserve just concluded its annual Jackson Hole symposium, at which Fed Chair Jay Powell used his keynote address to declare Fed victory over inflation and hinted at the promise of interest rate cuts in the very near future.

The battle over inflation has been won, and the battle to avoid recession soon will be won…right?

Ummm….no. The battle to avoid recession has already been lost. A good argument can be made that the economy has been in a rolling recession since sometime in 2022.

Framing and context are essential to understanding, so we will begin by reviewing Powell’s Jackson Hole speech.

Powell opened by summarizing the Fed’s rate hike strategy to fight inflation, and then declaring victory in that fight.

For much of the past three years, inflation ran well above our 2 percent goal, and labor market conditions were extremely tight. The Federal Open Market Committee's (FOMC) primary focus has been on bringing down inflation, and appropriately so. Prior to this episode, most Americans alive today had not experienced the pain of high inflation for a sustained period. Inflation brought substantial hardship, especially for those least able to meet the higher costs of essentials like food, housing, and transportation. High inflation triggered stress and a sense of unfairness that linger today.1

Our restrictive monetary policy helped restore balance between aggregate supply and demand, easing inflationary pressures and ensuring that inflation expectations remained well anchored. Inflation is now much closer to our objective, with prices having risen 2.5 percent over the past 12 months (figure 1).2 After a pause earlier this year, progress toward our 2 percent objective has resumed. My confidence has grown that inflation is on a sustainable path back to 2 percent.

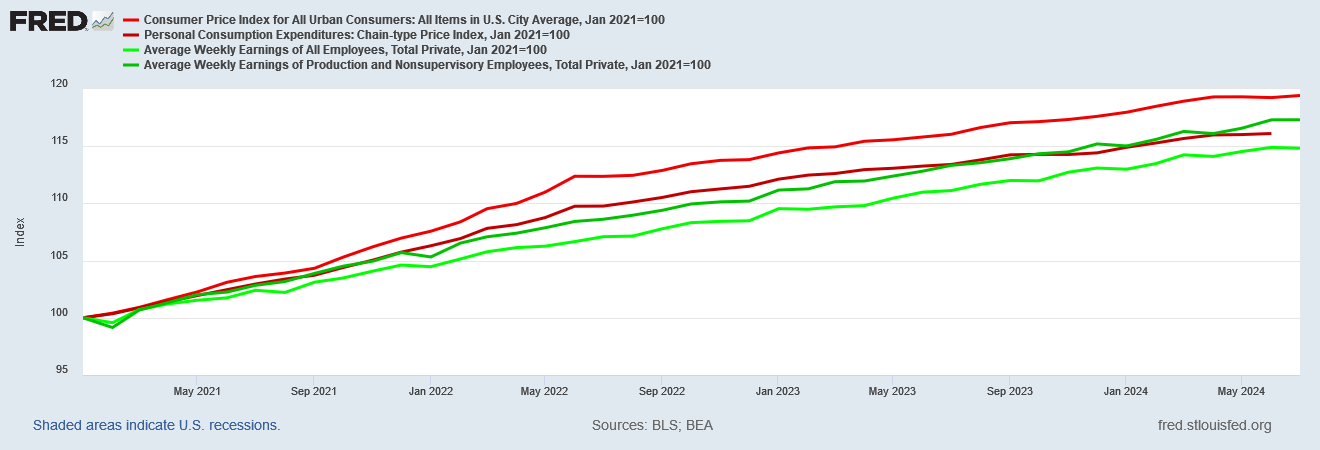

We must concede Powell correctly stated the basic facts about inflation. As measured by both the Consumer Price Index and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index, inflation has receded mightily from its 2022 hyperinflationary peak.

However, that Powell takes credit for the decline is at best a “generous” interpretation of the data. When we look at the timing of the Fed’s hikes to the federal funds rate relative to changes in inflation, it is mathematically impossible for them to have been all that impactful on inflation.

Inflation was already starting to peak by the time Jay Powell finally figured out that inflation was not going to be a short-term phenomenon (it only took him a little over a year!) and began pushing the federal funds rate up.

Even more damning is that the disinflationary trend that began in June of 2022 all but disappeared by June of 2023, with the CPI notching a meager 0.12 percentage point decline by July of this year, and the PCEPI coming down a bit more with a 0.68 percentage point decline.

From June of last year to June of this year Jay Powell’s rate hike strategy squeezed a whopping six-tenths of a percent out of the PCEPI. Wow.

Longtime readers will no doubt be unsurprised by the sarcasm, as I have maintained for quite some time that the Fed’s rate hike strategy was not impacting interest rates and prices the way Powell claimed it was.

Again, when we look at the historical interest rate movements for both corporate debt and treasuries, we see once again that the Fed was behind the curve throughout the rate hike period.

Corporate rates as well as Treasury yields began rising well in advance of Powell’s first rate hikes, and plateaued long before Powell was done hiking rates.

On both inflation and market interest rates it is always possible for the federal funds rate to have a delayed impact. Arguably, it could take a few months for a rate hike to be fully digested by the marketplace. However, lagging effects can only go one way. It is not possible for the Federal reserve to influence market rates with an increase to the federal funds rate months before the federal funds rate is in fact increased. If anything, the Federal Reserve did little more than respond to market sentiments on interest rates.

Did Powell’s rate hikes have any impact at all? Yes, they did. They made capital more expensive for the consumer.

Market interest rates truly do not give a tinker’s damn about what the Fed (or any other central bank) does with benchmark rates. However, those interest rates are reserved for Big Business and Wall Street. Consumers—meaning ordinary working-class Americans, who pay the prime rate from their local bank if they are lucky, and who get soaked by whatever interest rate credit card companies want to charge—are impacted directly and immediately every time the Fed futzes around with the federal funds rate.

We can begin to gauge the impact inflation and Powell’s rate hikes have had on consumers when we consider how much credit card debt consumers have accumulated since inflation began rising.

Jay Powell may not have had much impact on inflation. He’s had a considerable impact on consumers’ wallets, and not in a good way.

The final indignity regarding inflation that ordinary Americans have had to bear has been on the flip side of the equation. Prices have risen, consumer debt has risen, but paychecks not so much. From the start of the Biden-Harris Administration, worker compensation has failed to keep pace with inflation, producing a significant drop in real incomes.

Recognizing that worker paychecks are also an issue allows us to segue to the other economic concern Powell highlighted in his speech: jobs and employment.

Today, the labor market has cooled considerably from its formerly overheated state. The unemployment rate began to rise over a year ago and is now at 4.3 percent—still low by historical standards, but almost a full percentage point above its level in early 2023 (figure 2). Most of that increase has come over the past six months. So far, rising unemployment has not been the result of elevated layoffs, as is typically the case in an economic downturn. Rather, the increase mainly reflects a substantial increase in the supply of workers and a slowdown from the previously frantic pace of hiring. Even so, the cooling in labor market conditions is unmistakable. Job gains remain solid but have slowed this year.4 Job vacancies have fallen, and the ratio of vacancies to unemployment has returned to its pre-pandemic range. The hiring and quits rates are now below the levels that prevailed in 2018 and 2019. Nominal wage gains have moderated. All told, labor market conditions are now less tight than just before the pandemic in 2019—a year when inflation ran below 2 percent. It seems unlikely that the labor market will be a source of elevated inflationary pressures anytime soon. We do not seek or welcome further cooling in labor market conditions.

It is an odd sort of economic victory that Powell is claiming here. Labor markets were “overheated” so the way to “cool” them down is for more people to be unemployed.

Yeah, that makes sense!

Again, we should note that Powell did get the data right. The ranks of the unemployed has been rising since early 2023 or thereabouts.

However, what Powell overlooks is that the number of people not in the labor force—the number of people who have quit looking for work—began rising in early 2022.

People who exit the labor force do not show up in the unemployment data, which means there has been rising joblessness in this country which the unemployment numbers simply ignore. There has been rising joblessness in this country since early 2022.

For most people, rising joblessness is a bad economic trend. For the Federal Reserve looking for ways to justify their clueless rate hikes, it’s a positive “cooling” trend in an “overheated” job market.

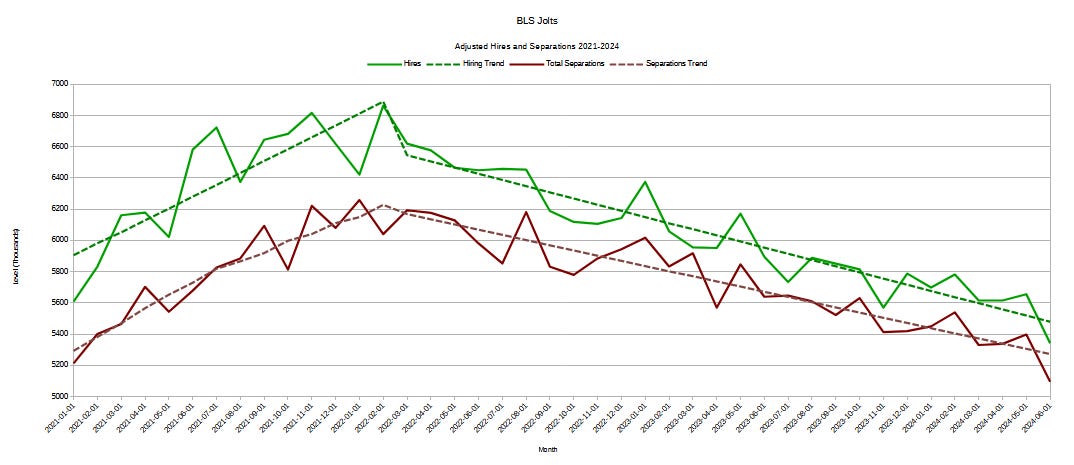

Powell also glosses over that hiring has slowed down. The pace of hiring in this country actually peaked in early 2022, and has been slowing down ever since.

The inflection point is clear and unmistakable—and is a leading indicator that a recession looms large.

We should also note that throughout the Trump Administration, hiring was on the upswing—even with the lunatic lockdowns from 2020 that scrambled everything.

However, the impact of the softening hiring trend is magnified by a separations trend that is softening as well, but not as quickly.

With rising unemployment, rising joblessness, and a slowing hiring pace, these are not indicators that point to economic expansion. These are indicators which point to economic contraction—i.e., recession.

Nor is this merely the arcane analysis of one individual. Even notional “experts” are assessing the economy to be either in recession or unavoidably headed towards recession.

“Every single one of us now believes there’s a recession, and that’s exactly the opposite of what the market believes,” Garry Evans, BCA Research’s chief strategist of global asset allocation told CNBC’s “Squawk Box Asia.”

Evans pointed to signs of the economy slowing down, including what he called the “deteriorating” U.S. labor market. The U.S. Labor Department reported that the unemployment rate inched to 4.3% in July to its highest since October 2021, and a gauge for U.S. manufacturing activity fell to an eight-month low in the same month.

It doesn’t help that the Manufacturing PMI has been falling for most of the Biden-Harris Administration, and has been printing outright contraction more often than not over the past twelve months.

Nor is it a positive sign that consumer confidence has weakened significantly since the start of the Biden-Harris Administration.

Overall consumer confidence is down dramatically from where it was at during the Trump Administration.

The presence of these additional indicators is compelling notional “experts” who would otherwise argue the economy is not in a recession to acknowledge that many consumers are already behaving as if it is.

Chris Markowski, of Markowski Investments, told Fox News Digital that Americans should not buy into the hype or "fear" of recessions. Instead, they should look at it as a "housecleaning" opportunity where they can make necessary cutbacks and come out stronger than before.

"I think many Americans right now feel that they're in a recession already," Markowski said. "Their buying power has been, in essence — it's gone away, based upon inflation and money and what it can buy them, what they're paying for groceries or what they're paying for cars and what they're paying for the bare necessities of life."

When consumers believe the economy is in a recession, the economy is in a recession!

Moreover, the jobs numbers argue for a recession beginning in early 2022. That inconvenient truth lends a decidedly delusional aspect to Kamala Harris’ Joker-esque cackle that “Bidenomics is working!” Not only is Bidenomics not working, Bidenomics has not been working since early in the Biden-Harris Administration.

Will Powell actually trim interest rates in the near future? Probably. In his Jackson Hole address he stated “the time has come for policy to adjust.” Having telegraphed rate cuts to the markets he will have a Wall Street rebellion on his hands if he does not deliver at least a few rate cuts within the next few months.

Will those rate cuts stimulate the economy and stave off recession? That seems unlikely. To achieve any significant level of macro stimulus, particularly within a torpid and sluggish labor market, the rate cuts would have to be significant and sudden, and there would have to be incentives elsewhere in the economic outlook to encourage additional consumption. Until consumers are able to digest the growing pile of credit card debt, even the decline in credit card interest rates which would follow a reduction in the federal funds rate can only have limited impact on consumer spending. Consumers need to pay down debt before they can dramatically increase their debt loads with new consumption.

The one clear benefit that will emerge from any Powell rate cuts is that the cost of consumer credit will come down as well. Market interest rates are already largely divorced from the federal funds rate manipulations that have been the favored tool for monetary policy since the Volcker era. The market rates did not move dramatically in response to the federal funds rate going up, and so it is difficult to conceive of an economic scenario where market rates move dramatically in response to the federal funds rate coming back down again.

However, the overall inefficacy of the Fed’s rate hikes and therefore rate cuts leaves the next Administration’s fiscal policy in a catch-22. Any large increase in spending—which equates to fiscal economic stimulus—is almost sure to push price levels back up again. Kamala Harris’ pledge of Nixonian price controls would not hold inflation down, but by further straitjacketing consumers they would hold consumption down, creating a perfect stagflationary storm. Without spending in areas such as housing, other policy goals move out of reach.

The next Administration’s economic challenge will be to find policy tools besides spending and leaning on the Federal Reserve to goose the economy and lift it out of recession.

Regardless of which candidate wins in November, the next President of the United States will get no economic help from Jay Powell. Powell is powerless to prevent the next recession—not the least because that recession is likely already here.

But, “Prosperity is just around the corner”, right?

Right?

If a band does a hip-hop version of “Happy Days Are Here Again”, I’ll know we’re in big. trouble.

Suppose Trump begins his next term in office by inheriting a terrible and worsening recession. The good news is that he will then have strong reasons to implement serious, even drastic changes. We could end up with a more free-market economy, fewer government bureaucracies, strengthened manufacturing, and all kinds of positive incentives to produce. Other politicians will have a hard time opposing any of it. Vote Trump!