China Is "Reopening", But Is It Too Late?

Is Economic Contraction And Collapse No Longer Avoidable?

As China shifts its Zero COVID message to the far more moderate tone of “Omicron is less dangerous”, China itself is having to contend with the impact of the easing of restrictions in places where lockdowns have long been the norm, including the shuttering of large portions of the Chinese economy.

For nearly three years the authorities have battled to keep Covid out of the country, using every tool of technology, mass mobilisation and repression at their disposal, regardless of the tragic costs to individuals and the terrible damage to the national economy.

China became a nation of vigilance, constantly on guard against the virus lapping at its shores. Xi Jinping, China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, was champion of this isolationist approach.

Now Beijing has decided to move on. Sun Chunlan, vice-premier and Covid chief, announced last week that the country’s health system had “withstood the test” of Covid-19 and China was in a “new situation”.

After years of telling its citizens that the only way to stay safe from Covid was to avoid it entirely, the policy pivot required a new message. Beijing has opted for presenting the prevailing Omicron variant as a less lethal version of the original disease.

While Zero COVID is still very much in effect, lockdowns are presumably to be of shorter duration and more targeted in nature—no more locking down entire cities over a handful of COVID cases (in theory).

This is, of course, the long-anticipated “reopening” of China’s economy. Thus comes the question, how stands the Chinese economy now?

And comes the answer: not very well. In addition to the disruptions and dislocations of the Zero COVID policy itself, China is being buffeted by the realities of a global economic recession and contraction, with diminishing demand abroad resulting in less economic activity within China itself.

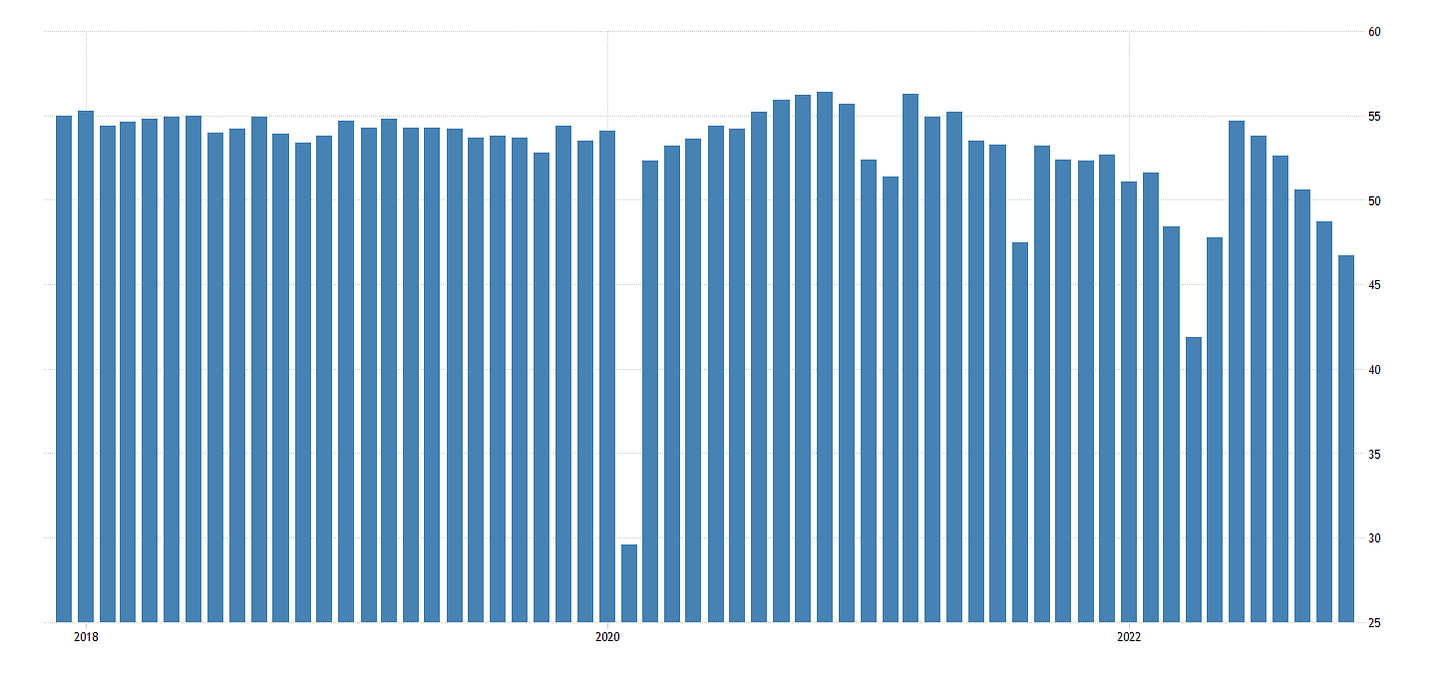

China’s own economic indicators tell the tale, with the manufacturing and non-manufacturing PMIs alike indicating contraction.

The official manufacturing purchasing managers index fell to 48 this month, the National Bureau of Statistics said on Wednesday, the lowest reading since April and worse than an estimate of 49 in a Bloomberg survey of economists.

The non-manufacturing index, which measures activity in the construction and services sectors, declined to 46.7 from 48.7 in October, also lower than the consensus estimate of 48. A reading below 50 indicates contraction, while anything above suggests expansion.

It’s not merely that the PMI indicators are registering economic contraction. The manufacturing PMI also declined month-on-month, highlighting the ongoing economic distress.

The non-manufacturing PMI has been contracting for even longer.

Moreover, the declining in manufacturing activity is likely to be fairly long-lasting, as the current contraction is also being matched by a decline in new orders for goods.

As regards new orders from the US, one of China’s primary export markets, the decline has been a veritable collapse.

U.S. manufacturing orders in China are down 40 percent, according to the latest CNBC Supply Chain Heat Map data. As a result of the decrease in orders, Worldwide Logistics tells CNBC it is expecting Chinese factories to shut down two weeks earlier than usual for the Chinese Lunar New Year — Chinese New Year’s Eve falls on Jan. 21 next year. The seven days after the holiday are considered a national holiday.

Whenever factories shut down for weeks at a time due to lack of business, that is never a good thing.

Yet it’s not merely the decline in export activity that is dragging China’s economy down. Domestic consumption, as measured by retail sales, has been declining for virtually all of the past twelve months.

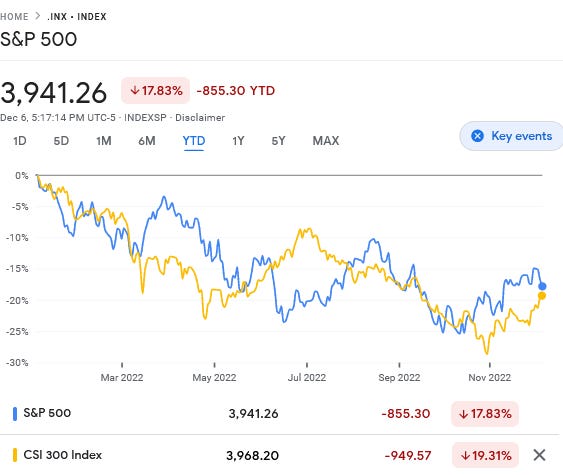

The across-the-board decline has pushed China’s stock markets into correction territory for the year, with all the major indices posting double-digit declines year to date.

Moreover, the decline has outpaced the stock market downturns in the US, with the CSI 300 index turning a worse performance for China than the S&P 500 index has for the United States.

With economies contracting the world over, China’s is leading the pack.

China’s real estate sector continues to show signs of collapse, with year-to-date new home sales in October posting their lowest reading in five years.

The dismal housing performance is in no small part due to the ongoing decline in new home prices, which have been contracting for the past six months.

The only reason the dollar-denominated bonds of China’s property developers—almost all of whom are under severe financial and liquidity stress—have shown positive returns recently is because Beijing has been walking back its policies towards the real estate sector, essentially unwinding the “Three Red Lines” debt deleveraging policy that helped to catalyze the sectors current collapse.

That builder-dominated bond market returned 20% overall in November, the best month since 2011 according to a Bloomberg index, after being battered for more than a year by a liquidity crunch that’s resulted in record defaults and an ongoing slide in new-home sales.

But moves to ease policy on the property and Covid fronts -- two key areas behind China’s slowed economic growth this year -- have resulted in a flip to market sentiment.

“Investors’ optimism toward still-standing names is on the basis that China’s ‘three arrows’ policy’” will bolster nondefaulters until home sales start recovering, said Zhi Wei Feng, a senior analyst at Loomis Sayles Investments Asia Pte. ANZ’s Meng expects quality developers to continue rebounding in early 2023, helped by “ample liquidity support from the government and commercial banks.”

China’s developers are surviving, not because of any improvement in housing markets, but because the government has thrown them not one but several lifelines, in the apparent hope that the developers will be able to return to significant growth once real estate finds its market bottom, wherever that should be.

While the Zero COVID policy has been a major contributor to China’s economic distress, it has not been the only contributor, and analysts estimate Zero COVID restrictions have negatively impacted at their worst roughly one-fourth of China’s economy.

As of Monday, the negative impact of China’s Covid controls on its economy fell to 19.3% of China’s total GDP — down from 25.1% a week ago, Nomura’s Chief China Economist Ting Lu and a team said in a report.

Last week’s 25.1% figure was higher than that seen during the two-month Shanghai lockdown in the spring, according to Nomura’s model. In early October, the figure was far lower, near 4%.

When the Zero COVID lockdowns take effect, their impact on the Chinese economy is undeniably broad, with nationwide infection waves reducing economic output in multiple cities simultaneously.

Yet, as the data shows, all of China’s economy is under duress, and has been even in between infection waves. Zero COVID has made the situation far worse, but even without Zero COVID China’s economy would still be in a state of contraction, as the impacts of a global recession and China’s real estate woes converge to drive the overall economy down.

The easing of lockdown rules and restrictions is allowing China analysts to talk of China “reopening”, but the economic reality is there is not much economy at the moment to greet that reopening. All the reopening ultimately accomplishes is setting an expectation that future economic activity will not be artificially suppressed by citywide and countrywide restrictions on people’s movements. The reopening cannot, by itself reverse industrial and property declines that are driven by forces that have nothing to do with the Zero COVID policy.

While the easing of the Zero COVID policy is an undeniable economic good, it is coming far too late to have much beneficial impact over the near term. The global economy is in recession, and China’s economy is leading the way. It will take far more than China’s government trying to get out of the economy’s way for China’s economy to exit recession and return to any significant level of organic economic growth. The window for easing Zero COVID to buffer the ongoing economic contraction has, at this point, closed.

China’s economy is reopening, but it is not going to resume growing any time soon, and hopes for economic improvement in the wake of Zero COVID’s easing are likely to be disappointed. The damage has been done, and it cannot be undone.

It's disheartening to consider that not only the dictators of the world, but most of its democratic leaders were oblivious to how social distancing has been like Kryptonite to national economies.