Fallout From China's Drought Is Getting Worse

The Autumn Harvest Will Fall Short. The Question Is How Short?

A picture is worth a thousand words.

In this instance, two pictures tell quite a story all on their own.

The first is a photo from China’s Guizhou Province last week, as officials inspect drought related damage to the region’s rice crop.

The second is a photo of a rice paddy in that same Guizhou Province just two years ago, with local farmers showing off the fish they were harvesting along with the rice crop that year.

From fish farming in rice paddies to dried up and cracked soil, as rice plants wither for lack of water.

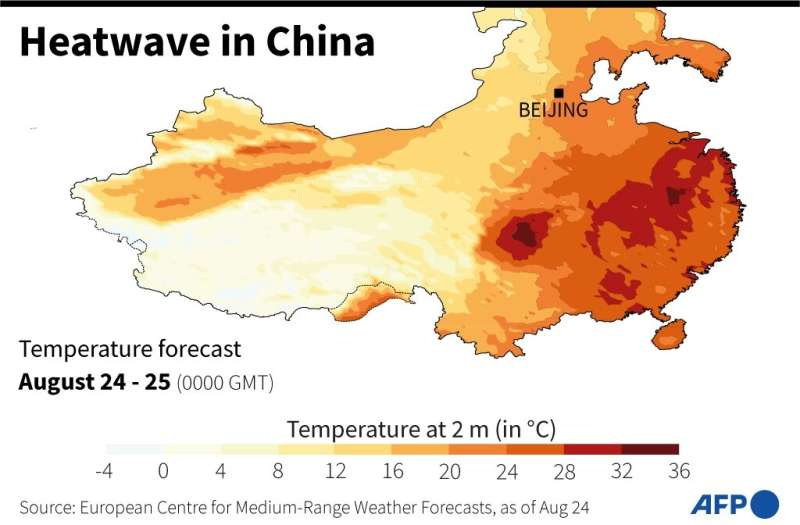

Similar images can be found throughout southern China, as the ongoing drought and month-long heat wave deprive China’s leading agricultural provinces of precious water.

That is the scale of drought in China today.

Not Just Guizhou Province

The list of provinces affected by China’s drought spans almost all of southern and central China. Dry conditions and record-setting high temperatures have been the norm for over 70 days across most of southern China, reaching even into the normally cool Tibetan Plateau.

While there has been some rainfall in Sichuan province, and the landfall of Typhoon Ma-On in Guangdong Province late last week is bringing much needed rain to some regions, high temperatures are expected to continue for a bit longer yet.

"High temperatures have basically been alleviated in the regions of south China, Jiangxi and Anhui," the meteorological administration said.

"But high temperatures will continue for the next three days in regions including the Sichuan basin and provinces surrounding Shanghai."

Just before the storm’s landfall, temperature records were being set throughout southeastern and central China.

Desperate Measures

Throughout the affected regions, local governments are in full crisis mode, resorting to a variety of measures to alleviate the drought crisis and get water to parched crops.

In central China’s Jiangxi Province, teams of drillers have been working up to 15 hours per day drilling new water wells.

Elsewhere, Chinese authorities have resorted to cloud seeding in an effort to force rainfall.

Amid record heatwave in China, authorities said at least ten provinces in central and southern regions used cloud-seeding planes to combat the heatwave.

Perversely, in some instances, the rain-inducing technology has proven almost too successful, as places such as Chongqing have had to issue flash flood warnings, as the sudden rainstorms produce more rain than the parched ground is able to quickly absorb.

It said that there will be five to eight rainy days, with precipitation 40-100 percent more than the normal level for the period, and isolated regions will see twice the rainfall typically seen.

"Therefore, residents in affected areas should prepare for flooding and landslide risks since the ongoing dry spell has left caked hillsides less able to absorb fast-moving waters."Zhang Yan, from the city's meteorological bureau, said that the ongoing heat wave in Chongqing is expected to ease, with daily highs in most parts of the municipality struggling to reach 35 C, and wide swathes of rainfall are forecast.

Overall, the drought-affected provinces are spending billions of yuan in emergency drought relief. Guizhou Province has issued an emergency subsidy of 65 million yuan for cloud seeding and water supply infrastructure. Henan Province, China’s largest grain producing region, had already allocated double that, 130 million yuan in drought relief. The Beijing government is spending 10 billion yuan on drought relief measures in addition to the provincial aid.

Rain Will Come Too Late

For many farmers, the rains expected over the next week or so will come too late, as their crops have already been largely lost to the drought. So many farmers are facing serious crop damage that China’s agriculture ministry is encouraging them to replant or switch to other crops that can be harvested later in the autumn.

In areas where the drought has already inflicted heavy damage, farmers are encouraged to switch to late-autumn crops like sweet potatoes, but that is no easy task.

“We can’t switch to other crops because there’s no land,” said Hu Baolin, a 70-year-old farmer in a village on the outskirts of Nanchang, Jiangxi’s provincial capital. He said his plants, including rapeseed oil and sesame, were far less developed compared to normal years, and his pomelos were just a third of their usual size.

As it stands, China is projected to import a record amount of rice over the next 12 months, to make up for the shortfall in rice harvests due to the drought.

For the average Chinese, the crop damage is already showing up in the form of higher food prices. Food price inflation ran 6.3% year on year in July, more than double June 2.9% year on year inflation rate.

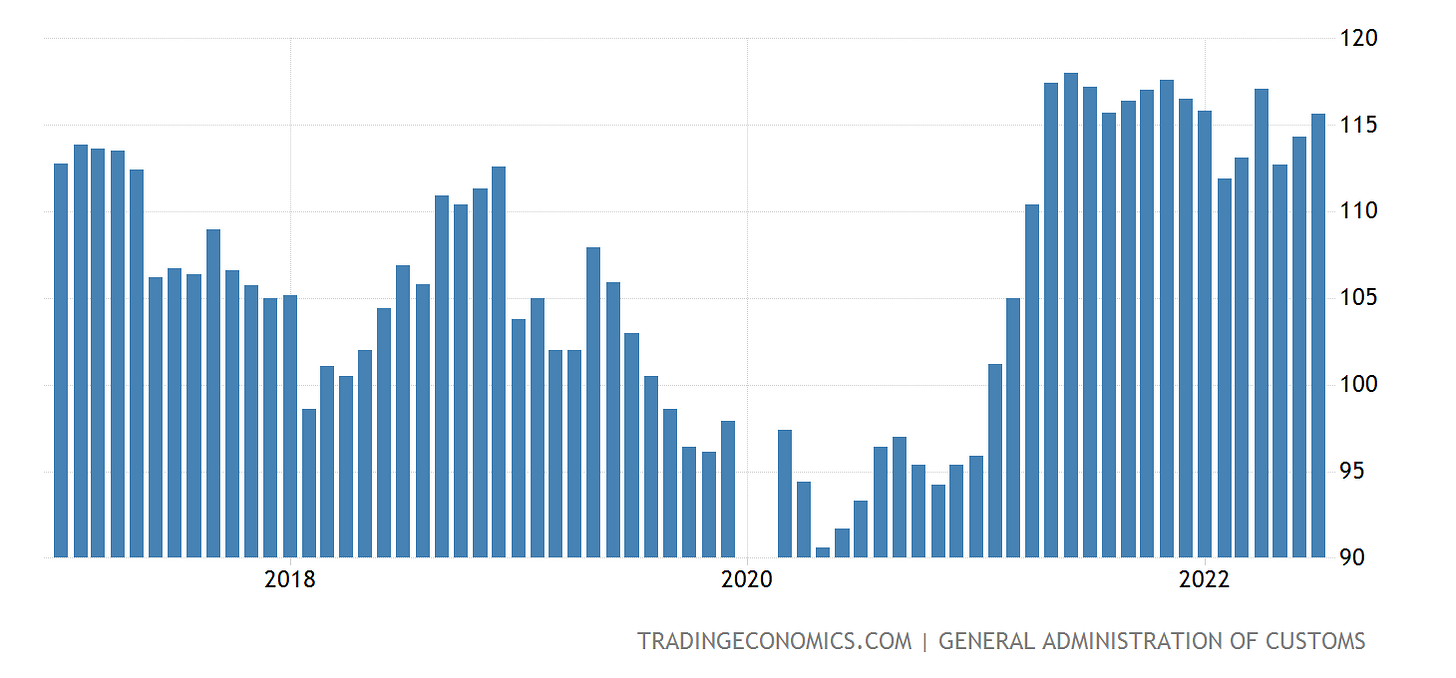

The rise in food price inflation is coming at a time when China’s import prices are also rising, making imported foodstuffs that much more expensive.

That the yuan has weakened against the dollar the most in nearly two years serves to further exacerbate import pricing, which means China will be paying more for imported rice and other foods during this coming winter.

Adding To Global Food Price Inflation

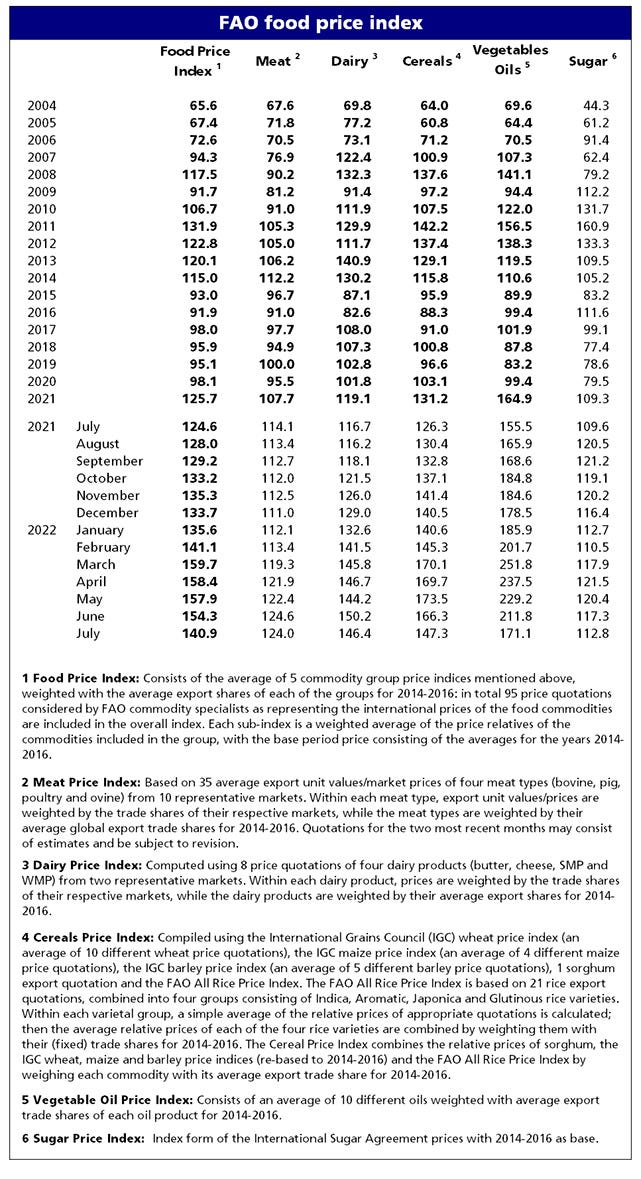

China’s need this coming winter for increased food imports is certain to exacerbate already significant global food price inflation. Although the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Price Index has declined in recent months, food prices globally are still running well above 2021 levels.

The FAO Cereal Price Index is 21 points higher than in July 2021, and the Dairy Price index is nearly 30 points higher over the same period. With the exception of sugar, every FAO food price category is up at least 10 points year on year.

A failed autumn harvest in China will push these numbers higher still.

Moreover, China’s drought is part of a global pattern of drought, and with the world facing an unprecedented third year of the “La Nina” phenomenon, where the equatorial waters of the Pacific cool, producing dramatic weather shifts around the globe, the agricultural outlook for 2023 is uncertain at best.

The future risks to Chinese agriculture from drought are best typified by the reality that the Yangtze River, which is normally at flood stage this time of year, is running at levels lower than it does during an average dry season.

China needs a lot of rain soon, or its agricultural output for next year as well as this year will be threatened.

No Famine…Yet

For now, there are no predictions of famine in China. China and famine have a lengthy history together, and so the CCP has made grain storage one of their ongoing priorities over the years.

Still, in China as in the rest of the world, food price inflation today means food insecurity tomorrow, with famine and hunger just one bad harvest or blighted crop away. With food price inflation already on the rise in China, and already elevated throughout the world, while China may not starve this winter, food insecurity is certain to be a rising concern for many, and if poor rain conditions continue into next year, China’s food outlook will only become increasingly grim, to where hunger and famine are no longer wild improbabilities, but eventual certainties.

Which is quite the turnaround from 2020’s celebratory photos of rice farmers harvesting fish as well.