Coronavirus: The Latest Legacy Media "Epic Fail"

Be skeptical. Trust nothing. Verify everything.

Whoever said "better late than never" did not work in journalism. They certainly did not cover a fast-moving story such as the coronavirus epidemic sweeping China and threatening the rest of the world.

Yet the legacy media has been tardy if not downright derelict in covering several significant aspects of this ongoing event. It was alternative media and social media that first called attention to the existence of the virus, officially named 2019-nCoV (also referenced as nCoV2019). It has been the alternative media and social media that has highlighted serious shortcomings and outright deceptions by Chinese officials and the state-run media.

Legacy Media Ignored Early Reports

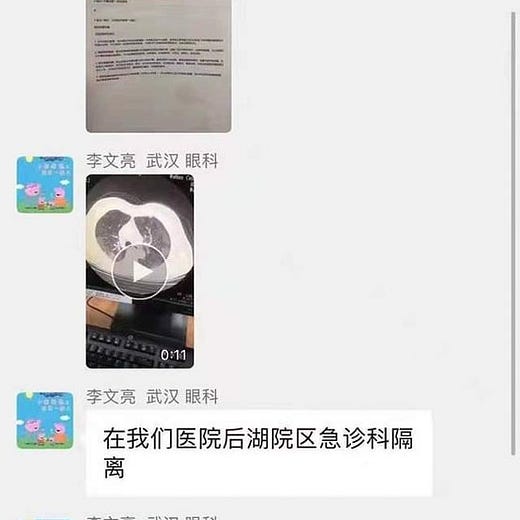

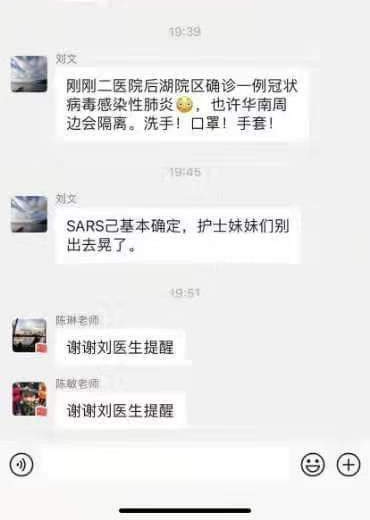

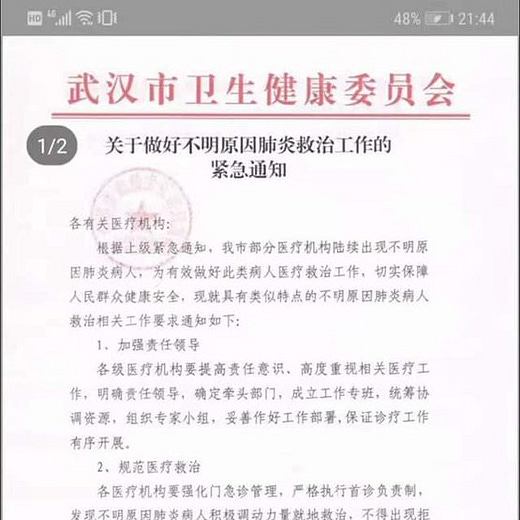

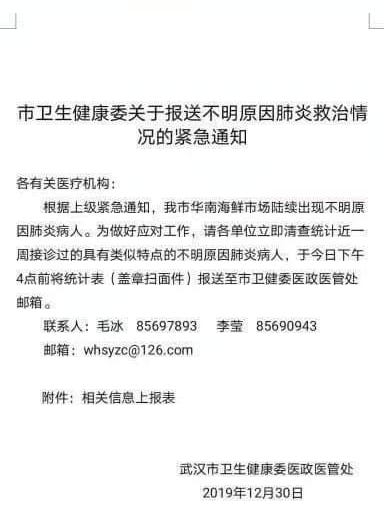

The earliest warning of the disease outbreak came on December 30, 2019, with the following tweet:

This was quickly picked up by Yaxue Cao of China Change.

Both tweets identified the association with SARS, the 2003 mini-pandemic that sickened some 8,000 people worldwide and killing almost 800.

The following day, the South China Morning Post reported on the Wuhan outbreak and the emergency measures being taken in Hong Kong. This article also noted a possible link to SARS. SCMP had a followup story on January 3rd, as Hong Kong escalated its response to the disease. On January 2nd, The John Hopkins Outbreak Observatory posted its initial advisory on what would become known as 2019-nCoV:

Reports emerged earlier this week about a series of unspecified pneumonia cases in Wuhan, in the Hubei province in central China. The circumstances of the outbreak have led to speculation that the outbreak is linked to SARS, but there is no evidence at this point supporting this assertion. At this point, details are still relatively sparse, but we will look briefly at what is currently known and attempt to provide some context for this emerging event.

In each of these initial reports, the link to SARS--a major global health crisis in 2003--was noted.

Only after the second SCMP story did the Associated Press pick up the story. Even then, it was not the legacy media but alternative media news aggregator ZeroHedge that gave the story wider distribution, pulling together the narrative threads from the SCMP and AP articles, and highlighting the health risks posed by coronavirus infections.

On January 6, Newsweek (a legacy media ghost at this point in its history), ran a story ruling out the SARS virus as the pathogen behind the disease. Also on that date, Time Magazine ran a story on the two cases of the disease identified in the United States and Bloomberg offered up a "quick take" segment.

From that point forward, the legacy media began giving the story more attention albeit still sporadically, with Reuters as well as the Associated Press filing more frequent updates.

A Google search of news on "coronavirus" shows these are the earliest reports in the legacy media on this disease--a full week after the first report of the disease in Hong Kong. A full week was allowed to pass from the first report of the disease to the legacy media giving the story even a passing notice.

On January 7, The Epoch Times picked up the story, as concerns about the virus in other Asian countries. To its credit, The Epoch Times has run regular stories on the disease since then.

The CDC weighed in on January 8 with a health advisory of a "pneumonia of unknown etiology":

According to a report from the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, as of January 5, 2020, the national authorities in China have reported 59 patients with PUE to WHO. The patients had symptom onset dates from December 12 through December 29, 2019. Patients involved in the cluster reportedly have hadfever, dyspnea, and bilateral lung infiltrates on chest radiograph. Of the 59 cases, seven are critically ill, and the remaining patients are in stable condition. No deaths have been reported and no health care providers have been reported to be ill. The Wuhan Municipal Health Commission has not reported human-to-human transmission.

The CDC also noted that SARS had been ruled out as a culprit, thus confirming that the disease was a completely new pathogen.

While one might be tempted to argue that stories take time to develop significance, one must also note two signature aspects of this story: 1) it originated in Hong Kong, which has been very much on the front page of every news site last fall, owing to the civil unrest during the build up to last November's historic elections, when Hong Kong delivered a stinging rebuke to Beijing; 2) from the very beginning similarities to SARS were reported.

A major city in Asia, one which had been very much in a media spotlight for months, initiates a major public health response over a disease with clear and documented potentials to become epidemic and the legacy media does not pick up on the story until a week later.

The legacy media chose the worst possible moment to lose interest in Hong Kong.

Given that Thailand placed a coronavirus patient in quarantine on January 13, how much might the world at large have benefited from greater media scrutiny starting from the first report of the disease in Hong Kong on December 30? Would China have been incented to initiate quarantine measures on a more targeted scale at that time, rather waiting until nearly a month had passed before attempting a mass quarantine of the entire city of Wuhan?

How many people need to become sick with a new disease before the legacy media takes notice?

The Legacy Media Slow To Report The Potential Threat Of Coronavirus

On January 22 Paul Joseph Watson of Summit News published an article reporting on concerns that the new disease could have a mortality rate as great as if not greater than the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic.

A professor has warned that the new deadly coronavirus which originated in China has the same kill rate as the Spanish flu, which claimed the lives of 20-50 million people in 1918.

Another Google search "coronavirus as bad as spanish flu" covering that same week reveals the legacy media reached that same conclusion a few days later.

The legacy media has also been reluctant to share videos posted on social media with dramatic and even shocking footage from Wuhan: people collapsing in the street from the disease, surrounded by healthcare workers in hazmat gear.

another case of collapsing on street in Wuhan.

see the mefics gear?its probably #WuhanCoronavirus related#Wuhan #WuhanPneumonia pic.twitter.com/aT6k9aHMCs

— 巴丢草 Badiucao (@badiucao) January 23, 2020

In any disease outbreak, the news is going to be fluid and often frightening. Yet people are not well served by a media slow to call attention to the worst case scenarios and more dire projections for what an epidemic might bring. The practical wisdom of "plan for the worst and hope for the best" is short circuited when people are not told what the worst case might be.

Yet here, as with the initial reporting, the legacy media has been slow to report research findings and other bits of "bad news". Much of the legacy media was focused on the rather obvious challenges of enforcing a quarantine of tens of millions of people on January 23 and 24.

The Legacy Media Has Been Slow To Report On Chinese Underreporting Of Cases and Deaths

From the start of the Wuhan quarantine, the reporting on the disease has been afflicted with a singular anomalous mismatch between the number of cases being reported and the extremity of the situation in cities like Wuhan. When there were only 850 cases reported in Wuhan, the health care system was already collapsing under the load:

But as the epidemic has developed, with the city on lockdown, hospitals are starting to run short of medical supplies and hospital workers are feeling the strain.

As was noted in other reporting, Wuhan is a city of 11 million people, and yet an influx of 850 new patients to the city's hospitals was enough to tax their capabilities.

It takes neither a rocket scientist, an epidemiologist, nor a statistician to recognize the sheer illogic of such a situation. A healthcare system equipped to handle the routine needs of 11 million people is overwhelmed by a sudden influx of patients amounting to less than 0.01% of the population?

To put it another way, as I did in A Voice Of Liberty's Minds Channel on January 24, "how badly is China fudging the numbers?"

ZeroHedge also highlighted the anomaly, and the cynical way China was gaming the release of updated statistics:

As we suspected, the virus has been claiming more victims. But the local authorities, who promised 'transparency' in everything virus-related, apparently felt the need to wait until 4 am local time to drop this massive bomb: Another 15 people have died in Hubei as hospitals struggle with severe shortages of nearly everything, including doctors and nurses. That brings the total number of casualties to 41. In addition, another 180 cases have been discovered in Hubei, bringing the total number of cases over 1,000.

Yet on the same day that ABC News was quoting French doctor Yazdan Yazdanpaneh saying that 2019-nCoV was less serious "than, for example, SARS", the South China Morning Post was demolishing both the initial timeline and the origin of the disease, revealing a patient had contracted the coronavirus as early as December 1, and had not had any prior contact with the Wuhan market initially cited as the origin.

The "less serious" version of SARS had been around for a month longer than earlier reported and the Chinese did not get around to revealing that little tidbit until a month after the outbreak was first recognized by Hong Kong. That surely qualifies as the Mother Of All "Oops".

Despite such errors and omissions, the media was filled with praise as late as January 29 for how China has handled the outbreak, with the WHO giving Chinese officials special mention for their efforts.

[WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus] was lavish in his praise of Chinese President Xi Jinping and other senior officials for their commitment to transparency during their “very candid discussions” in Beijing.

“I was very encouraged and impressed by the president’s detailed knowledge of the outbreak and his personal involvement in the outbreak. This was for me a very rare leadership,” said Tedros, a former Ethiopian health and foreign minister.

Not until January 31 did the Daily Mail publish an article recounting claims by people in Wuhan that the Chinese government was systematically underreporting the number of deaths in Wuhan, and covering their tracks by secretly cremating the bodies of the victims. At the same time, a doctor in Huanggang, a city of 6 million near Wuhan, released a video clip on Twitter alleging the government was underreporting the severity of the disease even there.

One day earlier, January 30, the Epoch Times posted a tweet with a video interview of a Wuhan resident disputing the official narrative of the progression of the disease in Wuhan.

It does not require a serious exercise of logic to see that these anecdotal stories match more to the measures the Chinese government is taking than the official narratives and statistics. As these photos from Wuhan illustrate, China is literally sealing the city off from the outside world:

Unknown Unknowns: We Do Not Know What We Do Not Know

The result of the shortcomings of the legacy media (and much of the alternative media as well) is that, more than two months into this disease outbreak, people still do not have a clear sense of how serious the disease is, how lethal it can be, how easily it will spread. To borrow from Donald Rumsfeld's pithy pontification on epistemiology, we do not know what we do not know.

We have had a month of reporting and we still do not know with certainty where 2019-nCoV originated. The Wuhan seafood market may have helped spread the disease, but if Patient Zero did not visit the market before he contracted the disease, it is far more likely a human brought the disease to the market, and not some bat or other animal.

We have had a month of reporting and we still cannot be sure what the actual mortality rate is. It might be a serious but not apocalyptic ~2% of cases, or it might be more lethal than the Spanish Influenza.

We have had a month of reporting and no one has explored the odd dispersion of cases--over ten thousand infections in China, but fewer than 150 outside of China. By way of comparison, during the SARS outbreak in 2002-2003, of 8,422 cases world wide, only 5,327 cases were in China. Given that the disease was in the wild at least a month earlier than initially reported, and given the large numbers of international flights between China and the US, as well as between China and Africa, it is surprising there are not more cases beyond China--the reasons behind that disparity might offer insight into effective quarantine and other containment strategies, yet this is not seriously being explored by the media.

Against disease, the only sure weapon any of us has is information. Had the legacy media elected to be a font of information and solid reporting, the coronavirus outbreak could have been the their golden opportunity to recapture some of the credibility it has lost due to its other more memorable journalistic missteps. Instead, they have merely managed to remind us just how untrustworthy they really are.

Trust Nothing. Verify Everything.

For better or worse, the inability of the legacy media to be a reliable information source on the coronavirus compels us all to look to our own information-gathering sources. We have to be our own newspaper, our own evening news. We have to take everything we see and read about the virus with a grain of salt, being fully prepared to be wrong about anything and everything,.

As people make plans and preparations for the disease they are well advised to always be mindful that the facts--especially the statistics--on the disease are going to be fluid. Numbers are not merely going to change, they are likely out of date by the time we read them, assuming they were accurate in the first place.

What the legacy media will not do, what many in the alternative media still have to learn how to do, people must now do for themselves: ask their own questions, do their own research. Glean facts from as many sources as possible.

Be skeptical. Trust nothing. Verify everything.