If you only consumed China state-run media, you would think that China’s economy is doing well, and even growing stronger. And you would be wrong.

Xinhua, China’s official news outlet, tried to play up the July Purchasing Manager’s Index data, all but ignoring what the numbers themselves actually signify—that China’s manufacturing sector is still in decline.

China's manufacturing sector witnessed an improved business climate in July as a key indicator went up for a second straight month, while the service sector continued to see vibrant activities, official data showed Monday.

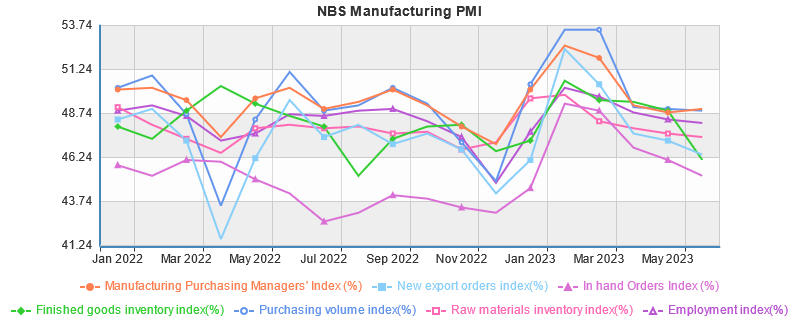

The purchasing managers' index (PMI) for the sector came in at 49.3 in July, up from 49 in June and 48.8 in May, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). A reading above 50 indicates expansion, while a reading below reflects contraction.

In typical spindoctor fashion, “improved business climate” translates into reality as “gets worse more slowly.” Which is what has been happening to China’s economy throughout 2023—slowly, steadily, it has been getting worse.

The sober reality of the Chinese economy is that it is underperforming, and has been underperforming for quite some time now.

Bloomberg, not being beholden to Beijing, offered up a more blunt and far less encouraging economic assessment than the state-run media.

Chinese consumers cut back on spending on everything but travel and restaurants this month, contributing to sluggish revenue growth in the country’s key economic sectors as the economy’s recovery loses steam.

Almost every major sector experienced a weakening in both revenue and profit margin compared with June, led by a steep slide in retail, according to China Beige Book, a US-based data provider. Sales in the travel and food and drinks businesses increased, defying the trend due to continued “revenge spending,” the firm said.

China’s manufacturing, which has showed signs of improvement in the previous months, also faces mounting headwinds. While output barely rose from June, domestic orders slowed, according to the survey.

Whatever recovery existed after the ending of Zero COVID last December has, by this point, well and truly gone, based on Bloomberg’s read.

As Reuters highlighted, China’s PMI data shows the manufacturing sector still very much in contraction.

China's manufacturing activity fell for a fourth straight month in July while the services and construction sectors teetered on the brink of contraction, official surveys showed on Monday, threatening growth prospects for the third quarter.

Construction sector activity for July was its weakest since COVID-19-related workplace disruptions dissipated around February, data from the National Bureau of Statistics showed.

What the media reports generally overlooked, however, is the extent to which China’s manufacturing sector has been contracting since at least the beginning of 2022.

While the headline Manufacturing PMI figure has only been declining February, when we look at the supporting indices going back to January of 2022, we see that for the bulk of that time, even the supporting indices have been flashing contraction signals for far longer.

The prevailing trend throughout the manufacturing sector since January, 2022, has been contraction. Long before Zero COVID ended, China’s manufacturing sector ran out of steam.

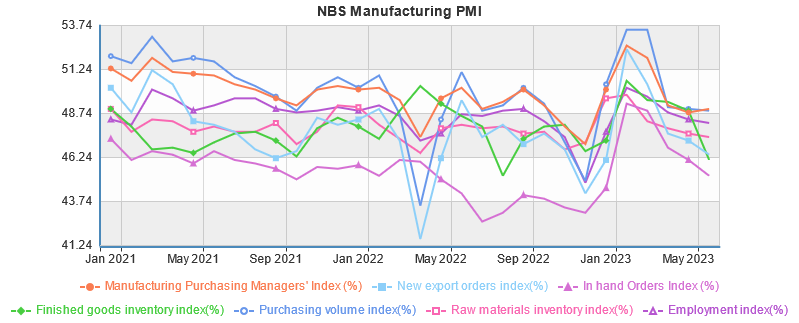

Moreover, even back in 2021, the official data showed that manufacturing had been weakening. China’s manufacturing sector has been deteriorating in terms of economic output for over two years at this point.

The publicly available data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics only allows one to go back 36 months, but if we review the macro data captured by Trading Economics, we can see that China's manufacturing PMI has been stagnating since sometime in 2018 at least.

The slight surge at the beginning of this year is proving to be just an outlier, and not a change in the larger trend. China’s manufacturing sector is in an extended multi-year decline, and is showing absolutely no capacity to reverse or pull out of it.

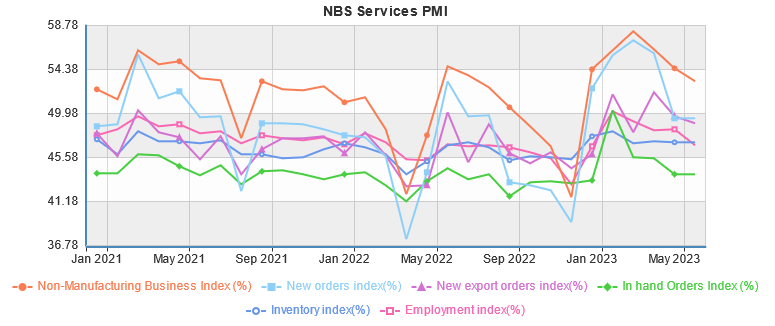

While China has been hoping that its domestic services sector would help buoy the poor performance of the manufacturing sector, even there the long-term trend has been one of gradual decline.

Ending Zero COVID provided a brief bounce, but that quickly faded, and the longer-term trend is beginning to reassert itself once more.

Significantly, while the headline Services PMI figure has been above the threshold of 50 which delineates expansion from contraction, since January of 2021, In Hand Orders has been significantly below that threshold. New Export Orders also has been in contraction for most of that time, with only a couple of momentary spikes above the expansion threshold. Service inventories have been in long-term contraction, and even New Orders has spent more time since January of 2021 below the expansion threshold than above it.

These are not positive long-term macro trends, but they have been the trend in China’s service sectors for well over two years now.

Nor is it merely the PMI data that points towards a long-term contraction for China’s economy. Even more telling than the PMI data are China’s factory gate prices. Factory gate prices, or producer prices—the prices Chinese manufacturing firms hope to obtain as goods leave the factory—have also been trending down over time.

Month on month, the headline Producer Price Index for industrial products has been trending down since January of 2022.

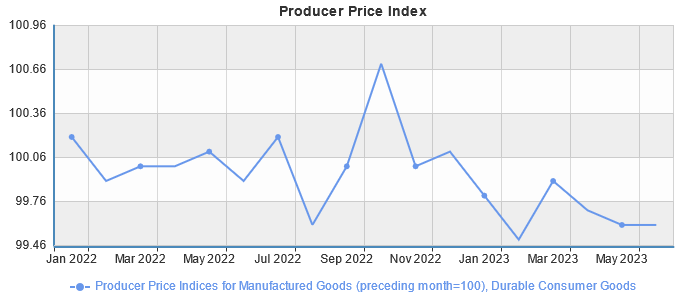

Factory gate prices for consumer goods, on the other hand, were actually trending up throughout most of 2022, but since around October, 2022, the PPI for consumer goods has been moving steadily down.

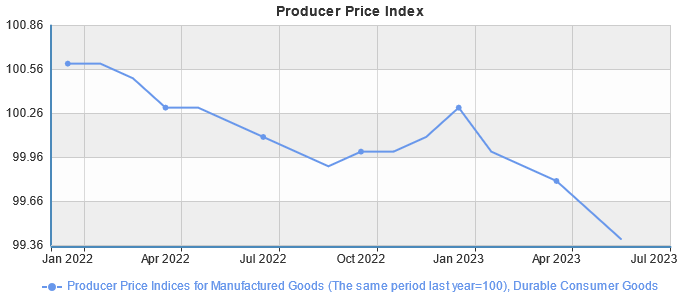

The price decline within consumer goods is fairly broadly based, with durable goods prices showing some of the most significant month on month declines over time.

Durable consumer goods in China have also been posting declining prices year on year since January of 2022.

Even producer prices for food have been showing a downward trend month on month since the fall of 2022.

The month on month declines in food prices mean that food price inflation, which had been rising in China year on year, as abated significantly with the disinflationary trend edging ever closer to outright deflation since the last fall.

Declining factory gate prices, whether on goods consumed domestically or goods produced for export, are indicative of only one thing: declining demand. The demand for Chinese goods, in both the domestic and international markets, has been steadily declining since at least the beginning of 2022.

Even more worrisome for China is that these pricing declines have been occurring even as the yuan has been depreciating against the dollar. Since January of 2022, the yuan has dropped by more than 11% against the dollar.

A weaker currency is generally considered to make a country’s exports more price competitive abroad, yet demand for Chinese goods has declined even as the yuan has weakened—which suggests that, absent currency arbitrage, the demand for Chinese goods has actually declined even more than the nominal data indicates.

Closer to home, the yuan has declined by just under 1.5% against the Australian dollar over the same period.

The one clear exception to this weakening trend has been against the Japanese yen, where the yuan has posted a 9.75% gain since January 2022.

That the yuan has been losing strength internationally is a complicating factor for Beijing. When export-oriented economies encounter downward demand pressures, one maneuver that can be used to stimulate export growth is to devalue the currency, and a recent report from the Institute of International Finance is reported to be advocating China do just that.

A recently published report by the Institute of International Finance (IIF) argues that currency devaluation could bring major economic benefits and spur China and others in and beyond Asia to experiment with this controversial weapon at a time of economic warfare.

China did in fact devalue the yuan back in 2015, ostensibly as a “free market reform” but in actuality in response to a significantly strengthening yuan, which had risen significantly against the Australian dollar as well as the yen by August of that year.

The 2015 devaluation produced some significant ripples throughout global financial markets, roiling commodity prices worldwide.

China has shocked global financial markets by devaluing its currency for two days running. August 11 saw a record 1.9% fall in value, followed by another 1% decline on August 12. The move by the Chinese central bank marks the yuan’s largest devaluation in two decades, sending a ripple effect across the regional Asian market and global financial markets.

Stocks, currencies and commodities came under heavy pressure as money managers feared it could ignite a currency war that would destabilise the global economy. Both the Nikkei stock market index in Japan and Hang Seng in Hong Kong were down more than 1%. Meanwhile the Singapore and Taiwan dollar both hit five-year lows on the news. It was a similar story for Indonesia’s rupiah, the Philippine peso, South Korean won and Malaysian ringgit.

The Australian dollar, which is often seen as a proxy for China’s currency, fell to a fresh six-year low of US$72.25, having been sold off heavily on Tuesday. Oil was hit, too, as well as key industrial and construction materials including nickel, copper and aluminium.

Presumably, a major devaluation by Beijing now would have similarly disruptive effects, although Beijing has recently offered assurances after the People’s Bank of China’s latest quarterly monetary policy meeting that it is committed to following through with what it terms “market-oriented reforms”.

The central bank has tried to assure the market that it is equipped with the necessary toolbox to maintain stability, and it emphasised the deepening of market-oriented reforms in the exchange rate system.

“The exchange rate of the Chinese yuan fluctuates in both directions, while remaining fundamentally stable at a reasonable and balanced level, serving as a stabilising force for the macroeconomy,” the meeting summary said.

With China’s economy showing multiple signs of deepening deflation across the board, the temptation to make a further devaluation of the yuan is almost assuredly significant, but any expectations for a dramatic shift on levels of global or domestic demand following such a move must be tempered by the reality that global financial markets are already devaluing the yuan, without producing any stimulation in either exported or domestic demand.

That China is facing a deflation scenario has been all but confirmed by recent reports of new stimulus measures all intended to boost consumption and demand.

China said it will announce new measures to boost consumption in the government’s latest effort to steer a revival in the economy after its post-Covid recovery at the start of the year fizzled.

Li Chunlin, vice chairman of the National Development and Reform Commission, and officials from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the Ministry of Commerce and the State Administration for Market Regulation will hold a press conference at 3 p.m. Monday in Beijing, according to a statement from the State Council Information Office.

These latest measures followed closely on the heels of a plan pushed out by China’s Ministry of Commerce to promote domestic consumption.

China released a plan to boost household spending on everything from electric appliances to furniture as economic growth slows, without providing specifics on the scale of support.

Local authorities should encourage residents to refurbish their homes, and people should get better access to credit to buy household products, according to the plan on boosting consumption released jointly by 13 government departments.

The measures come a day after China posted weaker-than-expected economic growth for the second quarter as retail sales cooled, the property market downturn deepened, and youth unemployment hit a new high.

The 11-point package is aimed at “unleashing the potential of household consumption,” according to the statement issued on the Ministry of Commerce website. The plan offered few specifics on the potential for direct cash support that many investors have been hoping for.

The latest stimulus package from the NDRC includes 20 various measures intended to promote consumption of “big ticket” items—essentially, homes and durable goods—and generally boost domestic consumption.

An important focus of the 20 measures released on Monday is stabilizing consumption of big-ticket items such as houses and cars. In terms of houses, the NDRC reiterated support for those buying their first homes and those seeking to upgrade their living standards. Specifically, the NDRC vowed to improve the basic mechanisms and support policies for housing security, expand the supply of affordable rental housing, and focus on addressing the housing problems of new urban residents, young people and other groups with housing difficulties.

How much impact the stimulus measures will have is debatable, however. As Michael Pettis, professor of finance at Peking University, tweeted out after the measures were announced, none of the stimulus measures do anything to expand household budgets, which limits how much overall demand stimulus is possible.

The reality of China’s economy is that the major economic actor is still the state—a phenomenon very much at odds with strategies to grow the economy by increasing household consumption.

The biggest reason for China’s anaemic consumer spending, if measured by the share of household spending in national GDP, is the country’s wealth distribution system, which favours the state.

Few countries in the world can rival China when it comes to throwing magnificent parties and erecting breathtaking architecture, but the nationwide per capita disposable income remained relatively low at 36,883 yuan in 2022.

If Beijing is unwilling to open its purse strings to increase consumption, it is highly likely there will be little or no increase in consumption—and in the wake of Zero COVID and a bursting housing bubble, Chinese consumers are considerably more nervous than before about consuming at any level, thus China’s household savings increased by 17.8 trillion yuan in 2022.

There is no escaping the mathematics of these economic variables. When savings increases, consumption and therefore demand must decrease, all else being equal. Decreasing demand is by definition economic deflation and contraction.

Beijing might want Chinese households to spend more, but it has been Beijing’s own policies over the past three years which has incented Chinese households to spend less.

The current economic slowdown unfolding in China is not merely a case of the post-Zero COVID “recovery” sputtering out. Rather, it is the reality of China’s economy having steadily deteriorated over time, in some regards extending back even before the COVID pandemic in 2020. The currency devaluation of 2015 itself was a major indicator of growing weakness in China’s economic model—reliance on housing markets and exports to push economic growth had reached its practical limit well before the first COVID case in Wuhan. What has occurred since has not had any good impact on the overall economy.

What Beijing is already too late in realizing is that Japan-style deflation and stagnation—a so-called “lost decade” of minimal growth and price declines—has already started. State-driven stimulus has succeeded in temporarily obscuring the realities of declining demand but has been unable to reverse them.

Can China stimulate its economy and return to earlier periods of heady GDP growth? Beijing certainly wants the world to believe that it can, and it is telling the world that it has the tools and the capacity to do just that.

However, the data is telling quite a different story. The data is warning the world that deflation is not merely coming to China, it is already there. The data is also warning that deflation is likely to take up residence in China for quite some time to come.

Unless China can find a way to reverse its current underperforming economic trends, it is facing at least one “lost decade” of minimal growth, deflation, and general economic stagnation.

And it was entirely self inflicted by the totalitarian technocrats in charge.

Time to short the renminbi!