Diesel Data Tells A Different Story Than The Narrative

Always Follow The Data, Not The Narrative

In a rare moment of confluence, corporate media and alternative media agree on a story—that the US (and ultimately the entire world) is facing a crucial shortage of diesel fuel.

Bloomberg casts the issue in grim and even borderline apocalyptic terms.

Within the next few months, almost every region on the planet will face the danger of a diesel shortage at a time when supply crunches in nearly all the world’s energy markets have worsened inflation and stifled growth.

Bloomberg goes on to describe diesel prices as “surging”, highlighting diesel’s 50% rise this past year in the New York harbor spot market, considered to be a benchmark for diesel prices overall.

Newsweek joins in the chorus with a listing of the states with the largest price increases for diesel.

The price of diesel has shot up across the country amid a supply crunch which is raising concerns among analysts that a severe, continued shortage might cripple the U.S. economy this winter and send already high inflation soaring.

Even alt-media mainstay ZeroHedge is joining in on the gloom-and-doom narrative.

A perfect storm in global diesel markets is unfolding. Refining capacities are tight, and stockpiles are being depleted as the Northern Hemisphere cold season begins. Supply crunches could jeopardize critical transportation networks since the industrial fuel powers ships, trucks, and trains. The fuel is also used for heating homes and businesses, as well as a power generation source for utilities.

Alas for the media, the data tells a rather different story, and highlights far different risks to the global economy.

Prices WERE Surging. Now They’re Declining

As Newsweek grudgingly acknowledges even as it spins a story of rising fuel prices, the general trend for diesel prices in the US has, ever since the summer, been one of decrease, not increase.

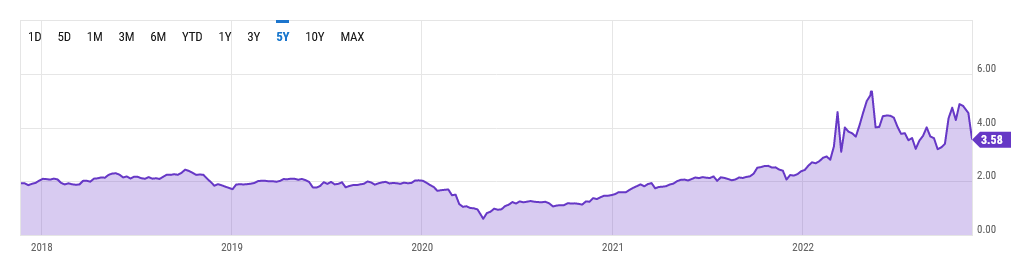

Diesel prices peaked in June of this year and have been moving down ever since.

Even the New York harbor spot prices are on the decline recently.

Which is not to say there was no surge in prices. Diesel prices did increase dramatically in February and March, and even the recent downward trend has not eliminated the impact of that increase. Viewed year-on-year, diesel prices are significantly higher, and represent a dramatic increase in fuel costs—and therefore transportation costs for almost every sort of good imaginable.

As the New York harbor spot prices for diesel illustrate, diesel prices are approximately double what they were in 2019, with half of that increase coming in just the past 12 months. The media is reporting that data point accurately.

Energy price inflation is very real, very significant, and very costly to all portions of the US economy.

But it is also important to recognize current pricing trends as well as the longer term trends. Particularly in fuel markets, prices are a measure of demand relative to available supply, and falling prices mean that demand relative to supply is easing. Regardless of the state of diesel inventories, the current trend for diesel demand relative to supply is lower demand, not greater demand. Falling prices admit of no other interpretation.

Inventories WERE Dropping. Now They Are Rising

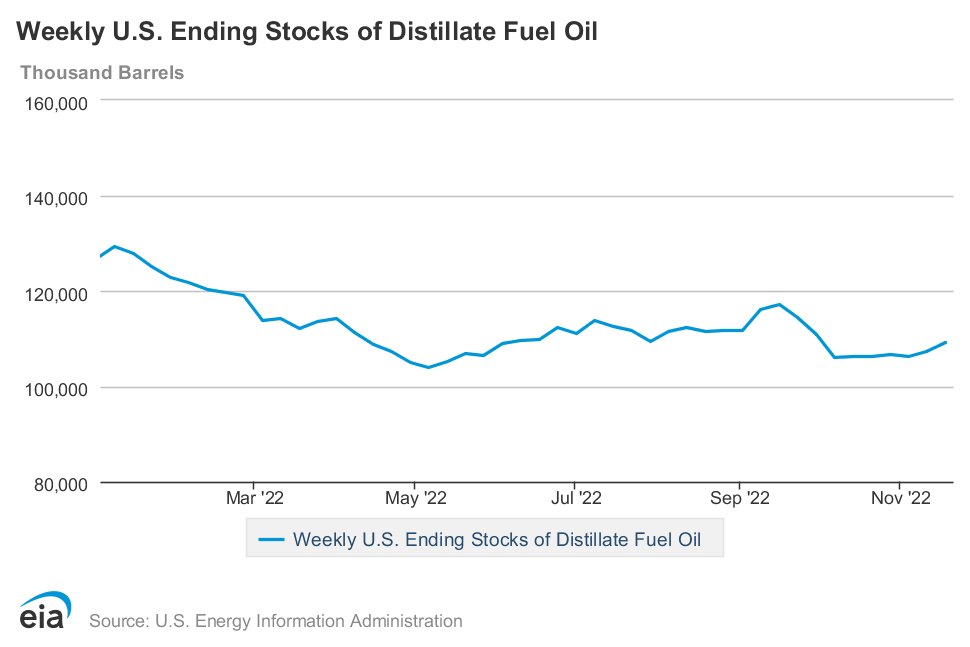

Just as diesel prices peaked, diesel inventories appear to have bottomed out.

At the beginning of October, US stocks of diesel were 106 million barrels, and have moved upward ever since.

The lowest inventory level for the year was back in May, at 104 million barrels, and until September, when there was a steep drop in inventories, the general inventory trend was increasing. That trend resumed after the October low.

Even when gauged by the number of days’ consumption represented by current inventories, the trend since October is up, not down. After reaching a low of 25.4 days’ supply in October, inventories have increased and now stand at 27.1 days supply.

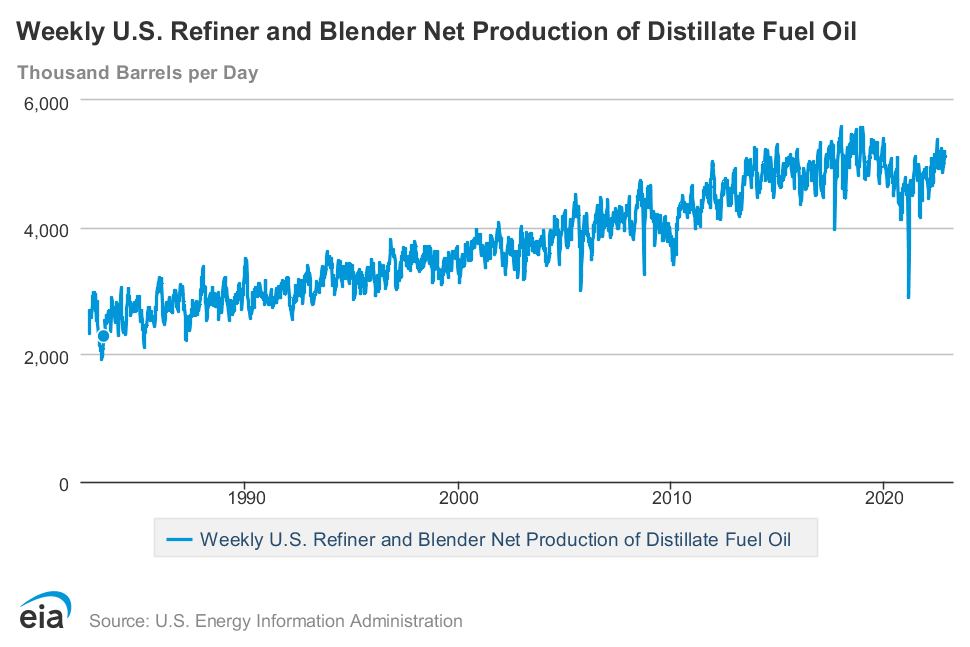

Moreover, diesel production in this country is currently also increasing, and is in the same range of output as this time of year in 2019, before the pandemic lockdowns upset every apple cart known to man.

Even the long-term trend for diesel is one of increasing production.

With falling demand and (for now) rising supply, a shortage of diesel becomes a mathematical impossibility.

Whither Future Demand?

The current reality of diesel demand in the United States is that demand is declining, at least relative to supply. As pointed out above, the recent downward trend in diesel prices does not admit of any other interpretation.

However, demand can and does vary, and the current decline is no assurance that future demand will also be in decline.

Indeed, with the Atlanta Federal Reserve projecting fairly robust economic growth during the fourth quarter, one could reasonably expect diesel demand to increase, as the overall demand for goods increases—and thus a greater need to transport goods to market.

The GDPNow model estimate for real GDP growth (seasonally adjusted annual rate) in the fourth quarter of 2022 is 4.3 percent on November 23, up from 4.2 percent on November 17. After recent releases from the US Census Bureau and the National Association of Realtors, the nowcast of fourth-quarter real gross private domestic investment growth increased from 0.4 percent to 1.0 percent.

However, that optimistic projection stands in stark contrast to what retailers and consumers are reporting as the holiday shopping season commences.

The National Retail Federation forecasts sales rising by 6% to 8% in November and December, well below last year’s record 13.5% increase. Retailers may have to discount deeply to attract shoppers, threatening profitability at a peak period.

Black Friday, the informal start of the peak shopping season, comes this week amid the muted backdrop. A Goldman Sachs survey of 1,000 US consumers found that nearly half plan to spend less this holiday season than they did in 2021.

Anticipated reduced retail sales and anticipated reduced buying by consumers indicates that future diesel demand will also be reduced relative to supply, and that any increase in relative demand will be, in the near term, marginal.

Beware Falling Demand

This decline in demand is by far the greater threat to the economy than any anticipated shortage. For a shortage to arise, demand has to greatly exceed supply. This would be preceded by a sharp rise in diesel prices, and a sharp decline in diesel inventories and days’ supply. Price and inventory trends are, at least for the time being, moving exactly opposite to what would produce a shortage of diesel.

But the decline in demand is, by definition, economic contraction. A decline in demand, particularly of a transportation mainstay resource such as diesel, is the very essence of a recession—and declining prices even as the days’ supply of diesel declined until recently means that diesel demand is declining, and declining by a significant amount.

Diesel prices are very much a red flag for the economy, as are diesel inventory metrics. However, the red flags are not of a looming shortage, but of a continued economic decline, of continued recession, and of a deep and getting deeper recession. Diesel prices are warning us that things are likely to get much worse before they get any better.

Diesel shortage is not the proximate threat here. A worsening economic contraction very much is.

Diesel prices alone do not mean the US is heading into another Great Depression—but they do indicate the US is getting closer to that outcome. That is the economic threat that should worry us all.

Diesel prices on the east coast this year have had a strong regional component to them as well, considerably more than can be explained by the difference in state taxes. Here in SE PA right now, it's difficult to find diesel for less than $6.00, and the price at many retailers is pushing $6.50. Yet I bought diesel in South Carolina last Sunday for $4.89 and in Florida a few days earlier for $5.09. Tax in PA is $0.75/gallon, South Carolina: $0.27, and FL $0.36. So $0.40-$0.50 if the price difference can be explained by taxes, and up until this year, prices were in line with taxes, but this year there's another $0.50-$0.60 regional difference that I can't account for.