Even The Houthis Can't Raise The Price Of Oil Much

Oil Markets Are Not Being Kind To Russia, Iran, Or Saudi Arabia

Historically speaking, wars in the Middle East tend to boost the price of oil worldwide. Whenever events threaten to disrupt the flow of black gold from the Persian Gulf, that stuff tends to get expensive.

It is quite remarkable, therefore, that despite repeated attacks on shipping in the Red Sea—on the other side of Saudi Arabia from the Persian Gulf—Iran’s Houthi proxies in Yemen have been unable to do much to push the price of oil up, scoring little more than marginal (and, so far, temporary) gains in the price of benchmark Brent Crude along with American West Texas Intermediate.

Shipping giant A.P. Moller-Maersk said Friday it will pause all container shipments through the Red Sea until further notice following a pair of attempted attacks on the Danish firm’s vessels and other maritime assaults by the Yemen-based Houthi rebel group against commercial shipping in the region over the last week.

Yet despite numerous missile attacks on Red Sea shipping, including attacks on US Navy ships patrolling the region, these obvious provocations by the Houthis—who are backed by Iran—have failed to widen the current conflict between Israel and Hamas in Gaza. More than that, there is little apparent sentiment among oil traders that the conflict will be widened, as evidenced by the downward trend in oil prices even in the immediate aftermath of the first Houthi missile attacks.

Oil traders did subsequently begin to reappraise the impact of the Houthi aggression in the Red Sea, but overall the impact of the missile attacks has been relatively muted.

Bearing in mind that the Houthi strikes come on top of Saudi and Russian production cuts, which briefly pushed up the price of benchmark Brent crude, one has to marvel at the glut of oil on the world market that must exist for these events not to discomfit oil traders, whose businesses hinge on at least some measure of stability in the Middle East.

As it stands, even the Houthi rebels are proving unable to do much to boost the price of oil, and barring significant change in the Red Sea situation, what impact they have had likely is only temporary.

Because the Houthis are backed by Iran, any discussion of their aggressions in the Red Sea must necessarily involve Iran. Indeed, from the very start of the Israeli-Hamas War there has been a certain amount of speculation that Iran has been something of a terror puppet master, manipulating its proxy terror groups and rebel militias across the region, including Hamas.

Does Iran benefit from such chaos? Potentially. Iran has ambitions regional hegemony among the Persian Gulf states. This could be the sort of muscle-flex that a power seeking to be seen as a Great Power might very well do. Moreover, so long as the fighting stays away from the Persian Gulf and the middle of the Red Sea, Iran can reap the benefits of higher oil prices, and perhaps even $100/bbl+ oil prices.

While there has been no real “smoking gun” providing a direct link between Iran and Hamas’ October 7th terror attack on Israel, Iran has long been the common denominator across the numerous terror groups and rebel militias in Gaza, in Lebanon, in Syria, and in Yemen with the Houthis. A presumption of an Iranian connection to the current violence in the Middle East is undeniably speculative, but it is not entirely unreasonable even so.

However, if we presume Iran is to some degree involved in instigating and sustaining the levels of conflict in the Middle East, in part at least to prop up the price of oil and thus help its own economy as well as that of other oil producing nations, current trends in the price of oil lead us to an inescapable conclusion: Iran’s meddlings are failing.

While events are continuing to unfold between Israel and Hamas, oil markets have assessed Iran’s saber rattling, as well as Saudi Arabia’s sabers, and concluded that there will not be a wider conflict.

Approximately one month after Iran first threatened to escalate the war, oil prices are back where they started before Iran made those ominous threats.

Eight weeks further on, and oil prices have moved even lower, and are now at levels last seen during the summer months, even after the price rises of the past week.

Applying a Great Power lens to the Middle East, it is not irrational to presume Iran has a hand in events currently unfolding. However, as already stated, looking at the price of oil, if Iran is attempting to manipulate the price of oil through an expansion of the Israeli-Hamas war, Iran is clearly not having much luck. Even if Iran is not directly focused on oil prices, falling crude prices still imply that Iran is not seen as having any success expanding the Israeli-Hamas war.

Nor can we overlook Russia. Whether Russia is involved in instigating Hamas’ October 7th attack or is merely a coincident beneficiary of events in the Middle East, even they are a potential player in the regional geopolitical melodrama.

There is little doubt that Russia would be a beneficiary of the US having its attention and resources redirected away from Ukraine. US munitions and missiles have greatly altered the trajectory of the war in Ukraine. How long could Ukraine fend off Russia should Western aid stop flowing? It is difficult to conceive of the answer being of any great length.

Further, Russia was a clear beneficiary of Hamas’ initial attack on Israel, as in the immediate aftermath the price of Russia’s benchmark Urals crude arrested its decline and recovered nearly all of its previous pricing—only to begin plunging again.

As of this writing, Urals crude has recovered somewhat and is now trading just above the EU/G7 price cap of $60/bbl, closing the other day at $61.82/bbl. This decline is not plausibly attributable to efforts by the EU or the G7 to enforce the price cap, which functionally collapsed back in the spring.

This decline in Urals crude means Russia is simply losing oil revenue, and the market pressures are no longer present which would incent Russia’s oil customers to circumvent the cap.

Should the Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping succeed in widening the Israeli-Hamas conflict, and thus push up the price of oil globally, Russia would be a clear beneficiary regardless of whether they were involved in either the initial Hamas attack or the various drone and missile strikes that have happened since. Similarly, if oil prices continue to decline, Russia will continue to see their oil revenues decline as well, and that will not bode well for Russia’s wartime economy.

Perversely, another beneficiary of Houthi efforts to expand the Israeli-Hamas conflict is Saudi Arabia, the longtime adversary of the Houthi rebels. Between soft oil demand, falling oil prices, and Saudi efforts to prop up the price of oil through production cuts, the Saudi oil economy has taken it on the chin over the past several months.

What has not been marginal, however, has been the consequence of oil price weakness and the Saudi production cuts on the Saudi economy. Saudi Arabia has been taking it on the chin with respect to its oil economy this year.

According to the flash estimates by the General Authority for Statistics (GASTAT), the real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Saudi Arabia decreased by 4.5% in Q3/2023 compared to Q3/2022. This result was due to the decrease in oil activities by 17.3%, while non-oil activities and government activities grew by 3.6% and 1.9% respectively, on an annual basis. (Figure1)

A 17% year on year decline for any economic sector in any country is significant. When it is the oil sector in Saudi Arabia, that decline borders on outright collapse, yet that is what happened to Saudi Arabia in the 3rd Quarter.

We should note also that the third quarter washout numbers came after a 3.8% drop during the second quarter—this decline is no fluke.

Even though Saudi Arabia is a regional rival of Iran and a competitor of Iran for regional hegemony in the Persian Gulf, an Houthi-Iranian effort to boost oil prices would be a clear economic benefit to the Saudis as well.

While there has been no indication of the Saudis taking any actions to support Hamas or disadvantage Israel, there is no ignoring the economic realities of oil and its significance to the Arab world. Virtually all of the major players in the Middle East with the exception of Israel would reap at least some economic benefit from rising oil prices, and if Iran were seen as the culprit behind the rise the Saudis might even stand to gain some geopolitical leverage from a possible renewed geopolitical isolation of Iran as a pariah state.

What the Saudis have been doing to prop up the price of oil has been to press forward with its Oil Sustainability Program—an initiative derided by some as a scheme to “artificially” increase oil demand in Africa especially.

A recent U.K. investigation by the Centre for Climate Reporting and Channel 4 News showed officials from Saudi Arabia’s Oil Sustainability Programme (OSP) admitting that the Saudi government is planning to boost demand in Africa and Asia for petrol, oil and diesel products, as part of a public program by the Ministry of Energy. In a recording, an undercover reporter asks, “My impression is that with issues of climate change, there’s a risk of declining oil demand and so the OSP has kind of been set up to artificially stimulate that demand in some key markets?” The Saudi official responds, “Yes. It is one of the aspects that we are trying to do. It’s one of the main objectives that we are trying to accomplish.” The official goes on to say that the plan is supported by the Saudi ruler Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The plan includes a fleet of power station ships off the coast of Africa, using heavy fuel to generate electricity. It also aims to develop technologies to launch ‘supersonic’ commercial aviation, which would require around three times more kerosine than conventional air travel. Saudi Arabia also plans to increase the number of combustion engine vehicles in the Asian and African markets to drive up fuel demand. Meanwhile, officials stated that they aim to counter market incentives and subsidies for electric vehicles at a global level, to maintain the international reliance on fossil fuels, particularly in emerging markets such as Africa.

Exactly how these measures would be an “artificial” stimulation of demand and not a structural expansion of it is rather unclear, but there is little doubt that Saudi Arabia recognizes that its near term economic future very much depends on a healthy price for oil worldwide. To that end, Saudi Arabia would much rather see that price rise because of increased demand rather than constrained supply. It has already done the constrained supply route, and the results have been far from kind to the Saudi economy.

With the number of major oil suppliers in the world who would benefit from rising oil prices, it is remarkable that oil prices have not staged a sustained increase in the aftermath of the October 7th attacks.

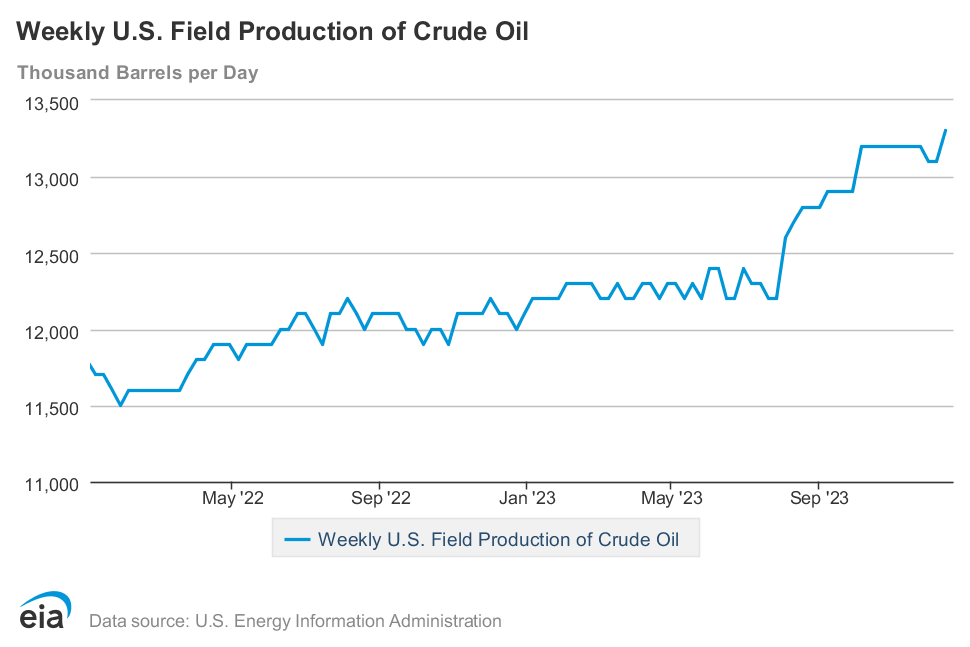

Surprisingly, a key factor in oil’s sustained price declines has been surging US production.

Crude oil production from the U.S. reached a new all-time high of 13.2M bbl/day in September, according to data released last week, outpacing expectations and causing a big problem for OPEC+, which agreed last week to further output cuts in an effort to prop up faltering prices.

The U.S. accounts for 80% of the expansion in global oil supply this year, according to the International Energy Agency, and its production is expected to grow by 850K bbl/day, well below the pace reached earlier in the shale revolution but much faster than analysts had forecast.

Despite the falling prices for West Texas Intermediate Crude—the other global benchmark oil price after Brent Crude—US oil production has been steadily increasing since late summer.

The US production increase since July 28 of 1.1 million barrels per day means the US has largely replaced the oil production withdrawn during the summer by Russia and Saudi Arabia. As a consequence, we are seeing the softness of global demand relative to global supply being highlighted.

When assessing oil price movements—or the price movements of any global commodity—it is important to recognize that demand is always going to be “strong” or “soft” relative to current supply. If supplies are reduced—such as after the Russian and Saudi oil production cuts—relative demand will generally become stronger and prices will rise. If supplies are reduced and prices do not rise, that is an indication that demand relative to supply is softening.

At the same time the US has been increasing production and thus global oil supply, China, a primary source of global oil demand, has been seeing its thirst for oil dwindle.

The oil demand outlook in China, the world’s biggest importer, isn’t offering much inspiration to bulls as the end of the year approaches.

Refining margins are falling, crude and fuel stockpiles are building and a hoped-for sharp jump in air travel still hasn’t eventuated. That’s mirroring the situation in the wider economy, where business and consumer confidence remain low despite government efforts to juice growth.

“Domestic demand has lost steam following the Golden Week holiday in October, and we don’t see any major supporting factors through winter,” said Mia Geng, an analyst at FGE. Gasoline and diesel consumption typically drop in the last couple of months of the year, and there could be additional downside risk as revenge travel seems to be wearing off in China, she said.

China’s crude imports did manage to increase by 7% in October from the previous month, customs data showed on Tuesday, but that came after a 13% drop in September.

Nor is China forecast to see the same levels of demand growth for oil in 2024 as it has in recent years.

China will see oil demand growth slowing next year, casting a pall over an already disappointing global picture for 2024, as the impact of pent-up appetite for travel and consumption following a three-year pandemic begins to fade away.

The world’s top crude importer will consume an additional 500,000 barrels a day next year, according to the median of estimates from 11 industry consultants and analysts surveyed by Bloomberg — less than a third of the increase seen in 2023. Petrochemical feedstock such as naphtha, and liquefied petroleum gas, or LPG, should account for most of the rise, along with jet fuel. Transport fuels such as gasoline, by contrast, are expected to become less significant as the electric-vehicle fleet grows.

The prospect of less-impressive Chinese consumption is already casting a long shadow. The International Energy Agency, in its November monthly report, said oil demand growth had been supported by “a narrow set of non-OECD countries, led by China” in 2023 — but it projected a sharp deceleration for the world in 2024 with a market surplus on the horizon, even with deeper production cuts from OPEC and its Russia-led allies.

With China leading a softening of global supply demand and the US leading a surge in global oil supply, it apparently is going to take more than a few missile attacks by the Houthis against Red Sea shipping to reverse the current downward trend in global oil prices.

US success in boosting oil production and the global softening of oil demand even in the face of a constant threat of expansion of the Israeli-Hamas conflict serve to highlight the fundamental weaknesses and fault lines being exposed in the overall global economy.

With the Chinese economy facing an extended period of consumer price deflation, with the US demonstrably mired in a recessionary stagflation in spite of the increase in oil production, with Europe ever on the brink of recession, the global economy is facing a near perfect storm of recessionary forces from literally all directions. There is not, at present, a major economy that has the upward trajectory necessary to prevent a recession and economic contraction from taking hold globally.

Without economic expansion somewhere within the major economies of the world, the only place for oil prices to go from here is down. Economic contraction worldwide invariably means less oil demand worldwide, which invariably means lower oil prices worldwide.

How weak is the global economy? So weak that even the Houthis’ best efforts to trigger a wider Middle Eastern war cannot significantly boost the price of the global economy’s most vital commodity—oil.

Lower gas prices, at least in some respects, is a nice Christmas present to those of us in the West dealing with high food prices. The prospect of the Houthis failing at expanding war in the Mideast is an even better present!

As for China, I read an interesting article in the Wall Street Journal’s 12/19/23 edition. (It’s behind a paywall, so I can’t link it here. I read it at the library.) Anyway, the ‘lying flat’ youth movement of China has now evolved to what is being called ‘let it rot’. Chinese young people, disgusted with their life prospects, are completely dropping out, moving to hippie-like rural villages, and having parties to celebrate their decision to ‘let it rot’. NOT a good sign for China’s economic future!