Germany And Spain: Splitting The Eurozone Economy In Two

Divergent Economies Create New Headaches For The ECB

The EU is one of those delightfully and reliably schizoid institutions that never fails to deliver a teachable moment about the insanity of our governing institutions. This past week has been no exception.

On Thursday, inflation numbers for Germany—the largest economy in the eurozone—and Spain—the number four economy in the eurozone—were published.

Inflation is pushing in different directions in Europe, rising in Germany and falling again in Spain, official figures said Thursday.

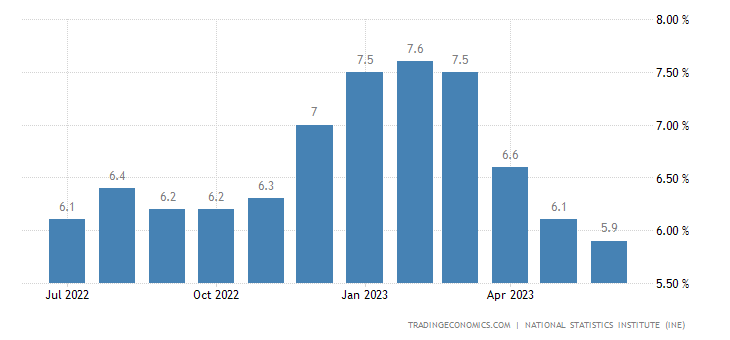

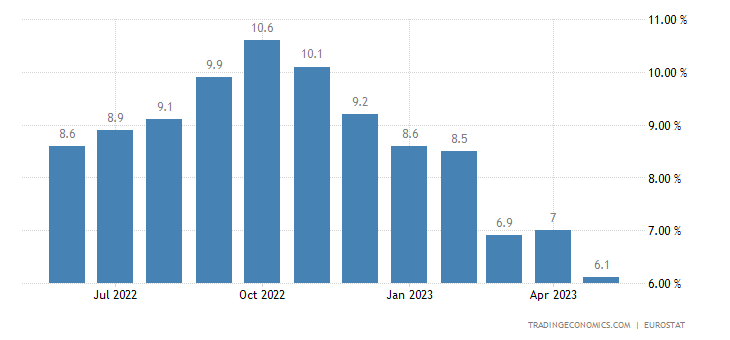

While Germany’s EU-harmonized inflation rate printed at 6.8%, half a percentage point up from May’s 6.3%, Spain’s harmonized inflation rate printed at the astonishingly low 1.6%.

One part of the EU has worse inflation than the United States. Another part has much better inflation than the United States. Somehow, Christine LaGarde and the ECB have to devise a coherent monetary policy for these increasingly divergent economies.

Even on its own, Germany’s economy would be a tough challenge for any central bank. Perversely fitting for the leading economy in the eurozone, Germany is already well along the path of stagflation, with rising inflation and falling output all at the same time.

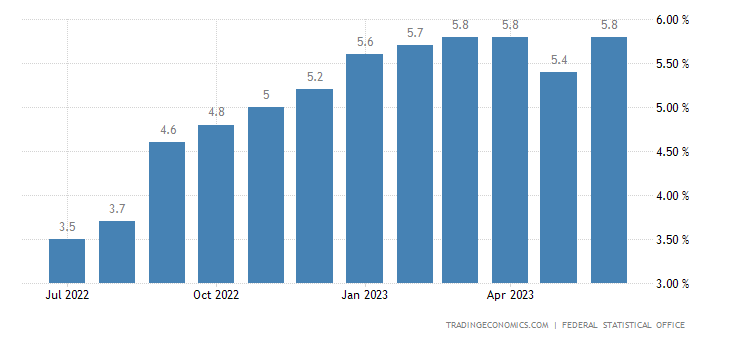

The inflation rise is an abrupt turnaround from the downward trend Germany has had in year on year inflation.

After 8 months of falling inflation, a 0.5% increase in a single month is quite the reversal. It is not a positive sign.

Making matters worse is that May’s reduction in core inflation turned out to be a one-off happening, with core inflation returning to the April level of 5.8%.

Since the beginning of the year, Germany has had the same problem with core inflation the United States has had since the beginning of 2021: core inflation is doggedly non-responsive to interest rate hikes. As with the Fed, the ECB’s rate hikes have had little or no influence on German core inflation.

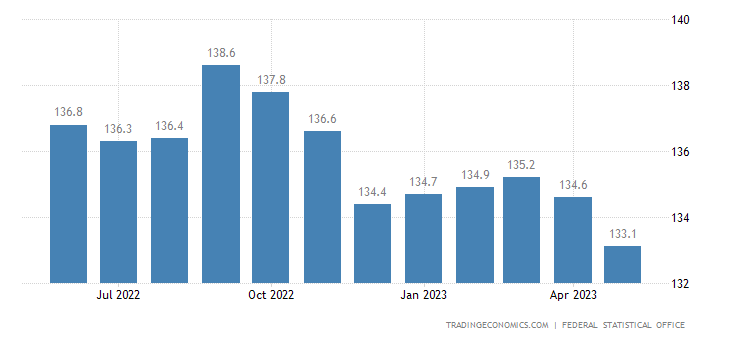

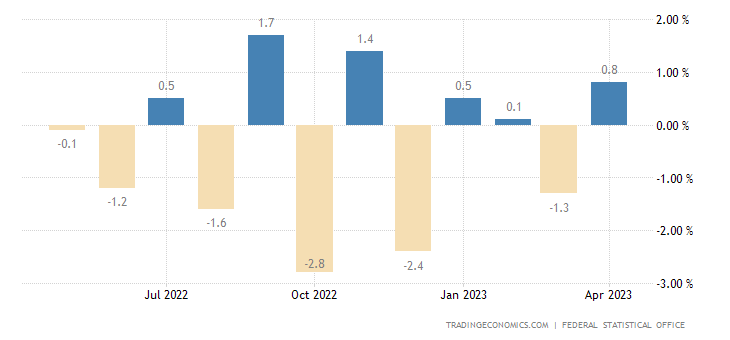

Ironically, while consumer price inflation has been rising, wholesale prices—a precursor to consumer prices—have been trending down.

Falling factory gate prices presumably should lead to falling consumer prices as well, yet consumer prices have moved steadily and determinedly in the other direction.

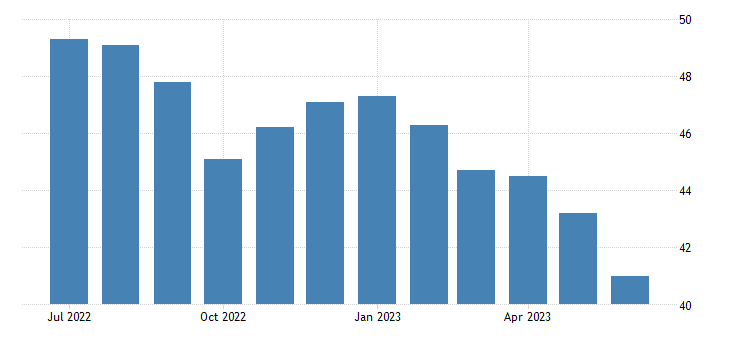

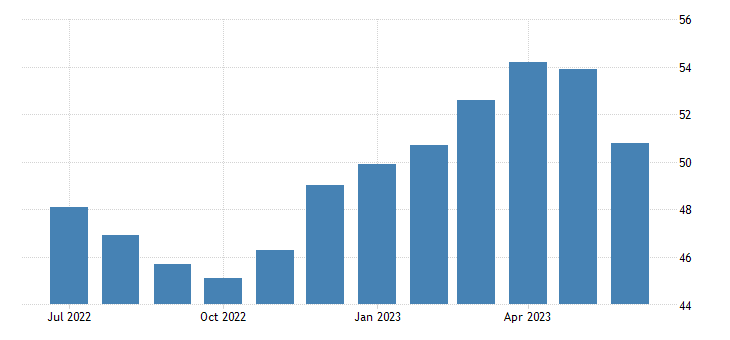

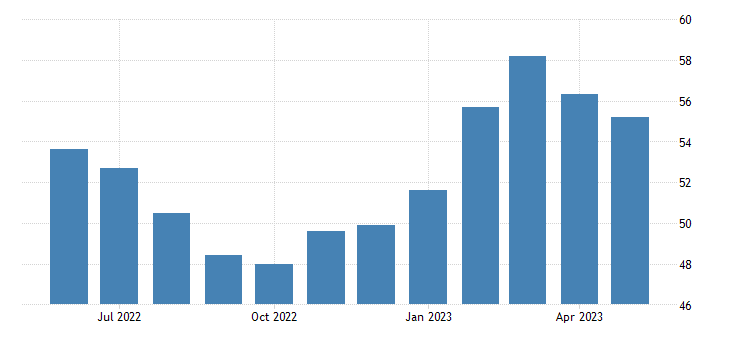

At the same time that prices have been rising in Germany, their Manufacturing PMI has been in a contractionary phase for the past eleven months.

Even their Services PMI abruptly declined by over 3 points, although it remained above the 50-point threshold between expansion (>50) and contraction (<50).

As a result of the twin declines, Germany’s Composite PMI softened as well, only just remaining above the 50-point threshold.

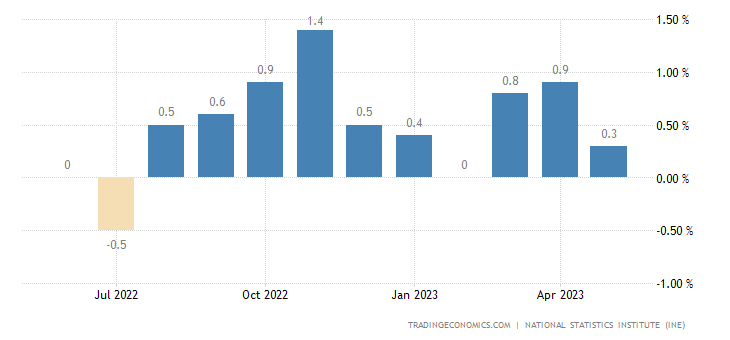

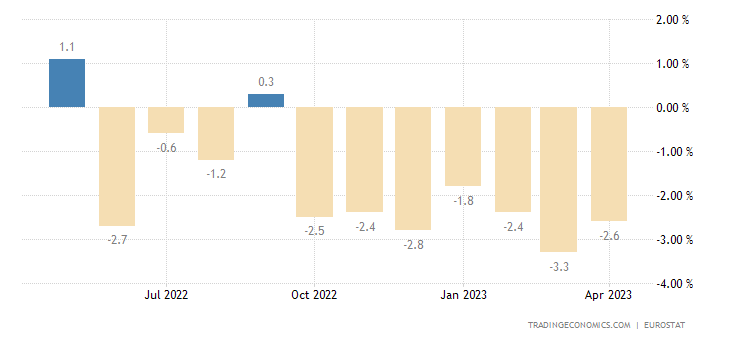

Compounding the irony of Germany’s stagflationary data is the continued decline of retail sales year on year, now having logged its twelfth consecutive month of decline.

Month on month retail sales actually improved, but show little sign of breaking out of the up-down pattern the numbers have been in for the past year.

That Germany is bogged down in a worsening stagflationary episode is reiterated by the PMI data, once again showing a shrinking manufacturing base while prices are trending up more broadly.

In addition to the macroeconomic data turning bad, Germany is also grappling with a rising number of business bankruptcies.

The number of corporate insolvencies continues to rise in Germany. In the first six months of this year, the credit agency Creditreform registered a total of 8,400 bankruptcies in Germany, as announced on Thursday. This means an increase of 16.2 percent compared to the first half of 2022. According to the experts, there was a higher percentage increase in the comparison period in 2002.

A trend which started last year as sanctions imposed on Russia as a result of the war in Ukraine started to bite (and bite back) has only continued and, with rising business failures, gotten worse.

At the same time Germany’s inflation problems are steadily getting worse, Spain’s are showing deceptive improvement.

Meanwhile, lower food and energy inflation meant Spain’s consumer price index increased only 1.6% in June from a year earlier, down from 2.9% in May.

Spain’s lower headline consumer price inflation figure comes despite food price inflation being in double digits.

With core inflation close to Germany’s at 5.9%, the greatly reduced headline number is due almost entirely to falling energy prices—like the US, Spain is experiencing energy price deflation, not just disinflation.

Strangely enough, Spain’s core inflation rate has until very recently been much higher than Germany’s, falling below 6% for the first time in twelve months just this past month.

Thus while on the surface Spain’s inflation woes are much less than Germany’s, peeling back the layers of the onion we find that their inflation data is divergent chiefly because Spain’s is more volatile.

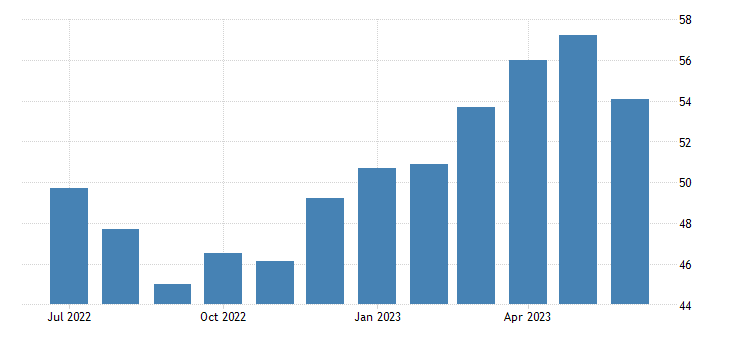

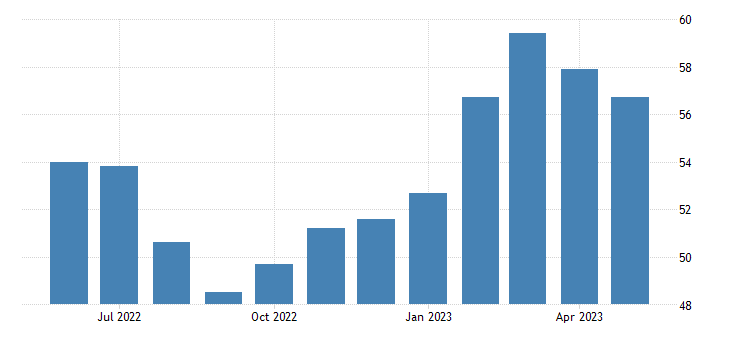

While Spain’s inflation problems have been more volatile, their economic performance has been in some regards more robust than Germany’s.

Unlike Germany, which has been experiencing manufacturing contraction for over a year, Spain’s Manufacturing PMI only dropped below the 50-point threshold in April.

The Services PMI figure, however, shows the same softening as Germany’s.

Unsurprisingly, the Composite PMI figure has followed suit.

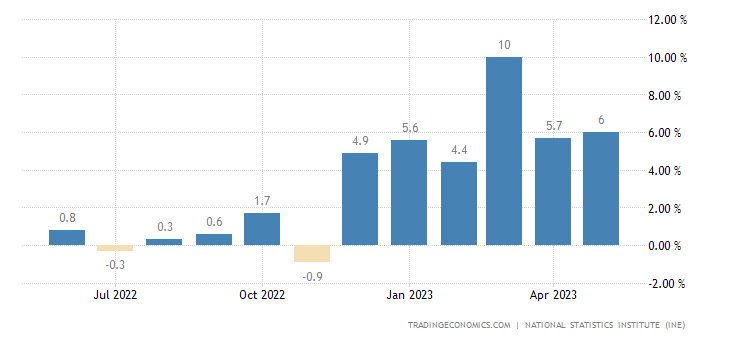

Where Spain’s economy is doing much better than Germany’s is in the area of retail sales. While Germany has been seeing its retail sales shrink steadily for the past year, Spain’s retail sales are actually growing year on year.

Even the month on month retail sales figures are better in Spain than in Germany.

Spain’s economy is far from healthy, yet it is considerably better off than Germany’s at the moment—an odd role reversal between the two countries, as Germany has been the traditional economic powerhouse providing much of the EU’s overall economic momentum.

This presents a distinct dilemma for Christine LaGarde and the European Central Bank. Spain’s economy is merely struggling, but Germany’s economy is sinking deeper and deeper into crisis.

Which situation should guide ECB monetary policy? How does a singular ECB monetary policy encompass the economic disparities brought into sharp relief by the divergent inflation statistics of Spain and Germany?

At the present time, the inside baseball thinking on what the ECB does next is that it intends to avoid considering country-level economic data, focusing exclusively on the eurozone inflation data.

Adrian Prettejohn, Europe economist at Capital Economics, said the low Spanish rate was unlikely to influence ECB decision-making “as country-specific factors are taking Spanish inflation much lower than in other countries.”

The prevailing opinion is that the ECB is betting on core inflation shifting substantially down during the second half of the year.

ING economist Carsten Brzeski said the disinflationary trend is likely to gain stronger momentum and core inflation starts to drop after the summer.

"The ECB will not change its tightening stance until core inflation shows clear signs of a turning point and will continue hiking until then," the economist added.

However, if the ECB bet is that core inflation is about to come down, it may very well be because the eurozone is tipping from inflation into deflation. Currently, the eurozone year on year inflation rate is below that of Germany’s—6.1% in May.

However, eurozone retail sales is only slightly better than Germany’s having posted declines in only ten of the past twelve months.

While the ECB has doubled down on its anti-inflation rhetoric, signaling that it will continue to raise its key interest rates until inflation finally comes down, increasing signs of economic contraction across the eurozone may force its hand.

With the economic impact of the Russian sanctions continuing to be felt—a situation that will endure for some time yet—how much economic contraction and decline can the ECB shrug off before it is forced to backtrack? How long before circumstances force it to cut interest rates rather than raising them?

While the ECB may want to take the economic high road and not have its decisions dictated by “country-specific factors”, the divergence taking place among the eurozone countries means that, regardless of the decisions the ECB makes next, ECB policy will increasingly help some eurozone countries and harm others. That in turn means that those “country-specific factors” are almost assuredly going to return to haunt the ECB no matter what it does.

The challenge facing the ECB is containing the economic divergences taking place within Europe, preventing that divergence from becoming disintegration. The reality facing the ECB is that there is no “one size fits all” strategy available given the growing disparities among the euro states.

Can the ECB hold the eurozone together in the face of an impending “lost decade” of stagflation? Over the last half of 2023, we may very well learn the answer to that question.