How The ILA Strike Might Drive Inflation

A Thought Experiment On Strikes And Logistics

At 12:01AM Eastern Time on October 1, 2024, the International Longshoreman’s Association went on strike as their 6-year contract expired without a replacement or renewal.

Billions in trade came to a screeching halt at U.S. East Coast and Gulf Coast ports after members of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) began walking off the job after 12:01 a.m. ET on October 1. The ILA is North America’s largest longshoremen’s union, with roughly 50,000 of its 85,000 members making good on the threat to strike at 14 ports subject to a just-expired master contract with the United States Maritime Alliance (USMX), and picketing workers beginning to appear at ports. The union and port ownership group failed to reach agreement by midnight on a new contract in a protracted battle over wage increases and use of automation.

Pretty much all freight traffic along the eastern seaboard—both the Gulf Coast and the East Coast—is effectively shut down for the duration of the work stoppage.

What happens now? And what are some of the likely impacts?

There is no great economic insight needed to understand that disruptions to supply chains and logistics will put a raft of new upward price pressures on all manner of goods. As I commented in one of my many Notes recently on the topic, “inflation is coming”.

How much could this impact consumer price inflation? What prices are likely to be most impacted by this strike? How will the particular price increases feed into the overall inflation numbers that will inform government policy in November and beyond?

These are the natural questions—and the right questions—to ask. Unfortunately, most of the answers are going to be some variation of “I don’t know.”

We can project many of the broad impacts, but none of these impacts takes place in a vacuum. The new price pressures are arising alongside a number of pre-existing influences that were going to push consumer price inflation in one direction or another regardless. That makes specific apprehensions of how much this will impact inflation an especially problematic exercise.

Still, to the extent we can understand how the dynamics of this strike will influence broader inflation, to that extent we can grasp the full significance of the strike itself.

(Note: I am going to refrain from commenting on the particulars of the ILA wage demands here. My thoughts on that aspect I will present separately).

Obviously, when a strike happens at a cargo facility, cargo stops moving through that facility.

What sorts of cargo moves through America’s eastern ports? Just about anything, from food to clothing to cars.

There are some early indications that pharmaceuticals might be among the products soonest impacted by the work stoppage.

Bills of lading, the digital receipts of freight containers, show that the delivery mechanisms for insulin and weight-loss drugs rely on East Coast ports for incoming trade.

“Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly are both heavily reliant on the Port of Norfolk,” said William George, director of research at ImportGenius, which tracks the customs data.

In the past year, Novo Nordisk has imported through Norfolk 419 twenty-foot equivalent unit, or TEU, containers worth of pharmaceuticals and injection devices that contain semaglutide, a compound in its branded weight-loss drugs, according to George. “Novo fine syringes commonly used for insulin injections come into the U.S. by ocean freight as well,” he said.

The impact of the strike largely depends on where in the world certain goods originate. Ports on the eastern seaboard primarily process freight from Europe and Africa as well as Latin America.

What many might not realize is the amount of food products which are imported into the US through ports on the eastern seaboard. For example, bananas, the most popular fresh fruit in the United States, is imported primarily from Ecuador, Guatamala, and Costa Rica, with 75% of of them being shipped to the east coast.

Other perishable items enter as well, and this presents an issue when a port is shut down for any length of time: what to do with the rapidly spoiling cargo?

Although bananas are relatively easy to ship, they require appropriate temperatures and humidity. Even under the best conditions, their quality deteriorates. Long delays will mean shippers will be trying to foist mushy brown bananas on consumers who might reject them.

Alternatively, banana growers may opt to find other markets. It’s reasonable to expect to find fewer bananas and much higher prices – possibly of a lower quality. Flying bananas to the U.S. would be too expensive to sustain.

Fresh meat and other refrigerated foods could spoil before they can complete their journeys, and fresh berries, along with other fruits and vegetables, could perish before reaching their destinations.

If there’s a port strike, tons of fresh produce, including bananas, that would arrive after Oct. 1 would end up having to be discarded. That is unfortunate, given the rising food insecurity rate in the U.S.

The time-sensitive nature of such cargo, however, also means that, to the greatest extent possible, shipments of such perishable items will get re-routed to the west coast, which ports are not out on strike at this time.

It is that impact of rerouting traffic to alternate ports which makes much of the inflation calculation problematic.

What is less problematic is that there will be some impact on consumer prices.

Even if goods are simply re-routed to west coast ports or offloaded onto land in Canada or Mexico to be delivered overland into the US, these various intermodal adaptations in almost every instance raise the proximate cost of various goods, and thus push up their price as well.

That certainty that there will some pricing impact also sheds some light on some of the broader networking effects from the price hikes and thus from the strike. As prices go up, so too do the price indices—thus headline and/or core inflation is impacted.

A significant uptick in either the Consumer Price Index or the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (the latter being the Federal Reserve’s “preferred” measure of consumer price inflation) becomes a data point the Fed will have to assess when it meets in November to decide whether or not to trim the federal funds rate again.

A large uptick in inflation could pressure the Fed to postpone a much-anticipated further rate cut.

Will there be a large uptick in inflation?

Possibly.

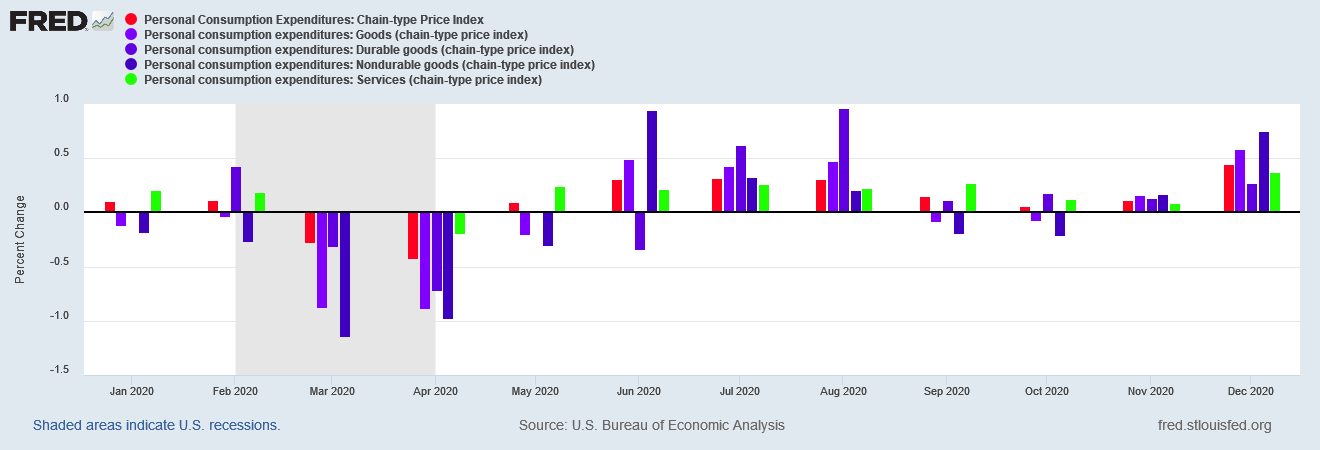

First, let’s define “large”. During 2020, in the immediate aftermath of the Pandemic Panic Recession and the ensuing lockdowns, durable and non-durable goods prices both displayed month on month increases of close to 1%.

These increases in goods prices quite naturally pushed up the overall PCE Price Index (I am focusing on the PCE Price Index for the remainder of this discussion because of its natural breakdown into broad categories goods and services, which makes simplifies the presentation somewhat).

How much of an increase to headline inflation a particular uptick in goods prices produces depends on the overall mix of inflationary pressures. In 2020, for example, there was much less service price inflation than we see today, and this presented as a buffer to overall price inflation. Thus when either durable or non-durable goods surged in 2020 to nearly 1% month on month, the overall PCE Price Index rose only about 0.3% month on month.

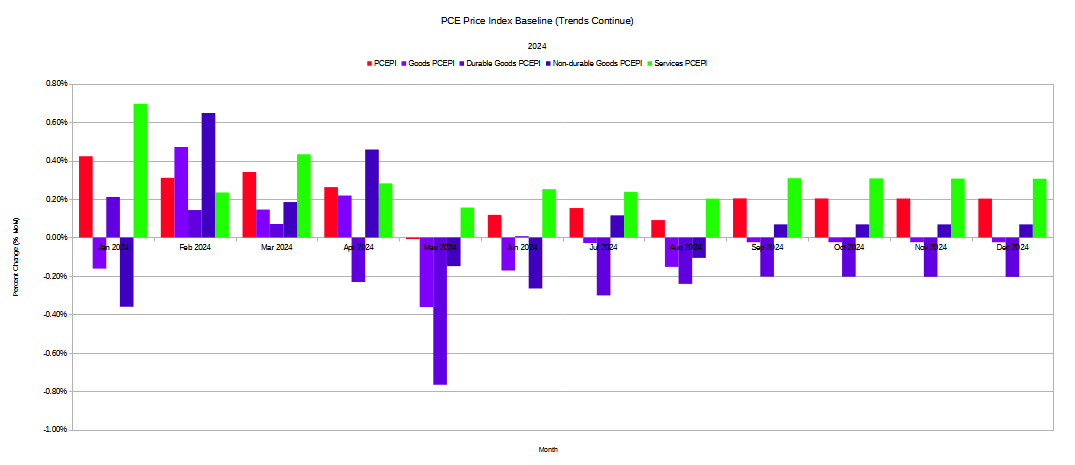

Thus far in 2024, we have seen a dramatically different inflation picture within the PCEPI.

In addition to having much more significant service price inflation, particularly earlier in the year, we also have had throughout most of the spring and summer goods price deflation—prices have been coming down, not merely rising more slowly.

Without the strike—if we assume that there is no change in the overall mix of pricing pressures—and we extended the current trends for the PCE Price Index and the broad subindices, we can extend the graph above out to the end of the year, which then looks like this:

If current trends held, what we would see is continued goods price deflation, and continued service price inflation.

Intriguingly, if we are merely extrapolating the current trends for each of the related indices, headline inflation per the PCEPI actually ticks up a bit for the end of the year, to about 0.2% month on month.

No matter what happened with the longshoreman, in other words, we were looking at a small uptick in consumer price inflation no matter what.

Since the longshoreman did go on strike, however, the one thing we know is that the baseline scenario is the one which absolutely will not happen. We have the strike, we have the disruption to flows of goods and services, so we know that there is going to be an impact different from the baseline trend.

There is no way to assess how particular prices will move specifically the longer the strike drags on. Even attempting to assess specific shifts in overall prices is little more than a guessing game.

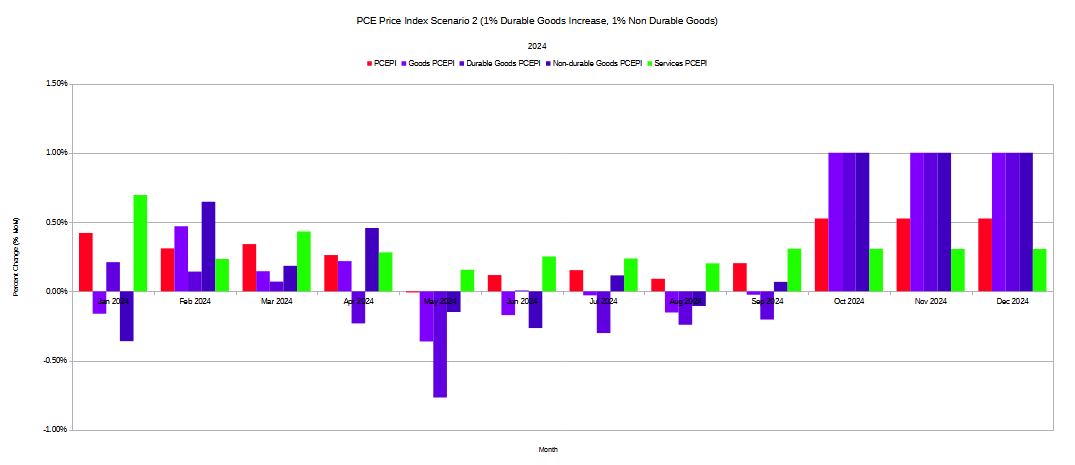

However, by making a few such “guesses”, we can see how various price impacts on specific goods might bubble up to the overall price index on goods and, in turn, on the headline PCE Price Index itself. In other words, we can assess what sort of inflation numbers we will see reported come November, December, and possibly January.

The structual logic of the PCEPI data set allows us to do this sort of thumbnail modeling. Because goods prices are broken down into durable and non-durable goods, and because goods are then aggregated with services to get the overall PCE Price Index itself, we can look at the Personal Consumption Expenditures data itself to gauge how to weight changes to the various subindices.

When we weight the price index for non-durable goods and the index for durable goods according to how much each category contributes to overall goods expenditures itself, we can aggregate the two indices to assess what the goods price index would be. By repeating that process with goods and services, we can assess what the overall headline PCE Price Index would be.

Thus it becomes possible to approximate how much overall inflation we would see in the PCEPI data if the strike produces a certain amount of price inflation for either durable or non-durable goods.

For example, if we posit the strike will produce a 1% increase in durable goods prices, and a 0.5% increase in non-durable goods (a 1% increase being what we saw during the dislocations from the lockdowns, which a strike approximates), while sustaining the current trend in service price inflation, we end up seeing a 0.67% increase in goods prices and a 0.43% in overall price inflation month on month.

If we posit that both durable and non-durable goods experience 1% of price increase month on month from the strike, that means overall goods inflation is 1% month on month, and headline inflation rises to 0.53% month on month.

If we posit an apocalyptic 2.5% increase in durable goods prices month on month, and a 2% increase in non-durable goods month on month, overall goods price inflation rises to 2.17% month on month, and headline inflation very nearly hits 1% month on month (0.91%).

In other words, depending on how much goods prices are pushed up by the strike, we could see a significant uptick in overall consumer price inflation.

Moving those monthly percentages to the year on year percentages we routinely see reported, these shifts in the PCE Price Indices result in year on year inflation of 3.2%, 3.5%, and 4.5% by December—assuming the strike and its impacts last that long.

In other words, depending on how this strike unfolds, we could see consumer price inflation move up by at least a full percentage point year on year by December. In an apocalyptic scenario, we could see year on year price inflation double from where it was reported for August.

Are these projections of how much inflation we will see? Not at all. These are scenarios, and the increases were picked out of thin air. I do not have data sufficient to allow me to predict that durable and non-durable goods prices will increase by any percentage, let alone the ones applied here.

But what this exercise does illustrate is the level of sensitivity within the overall price index to the particular price shifts this strike will eventually cause. When goods become scarce their price goes up. When supply chains get tangled the prices of goods goes up. This is the natural consequence of disruptions to available supply—a sudden shock of scarcity.

Nor are the prices themselves necessarily the result of a bottleneck at the eastern ports. Re-routing goods to the west coast may result in higher transport costs, and thus push prices up. If goods are re-routed to Mexico and Canada and then delivered overland into the United States that again would push costs and therefore prices up.

Even resolving the strike and granting the ILA members their sought-after wage increases, as an increase in overall port costs, could push prices up.

Now that this strike has begun, we are absolutely going to see at least some price increases, and the headline inflation number is itself going to rise. Even without the strike headline inflation was already set to rise incrementally no matter what.

We should also note that the PCEPI tends to be the more subdued of the two widely reported consumer price metrics. The CPI historically displays much greater volatility and both month on month increases as well as year on year. If a pricing scenario produces 1% month on month in the PCEPI, there is a better than even chance that same scenario will produce more than a 1% month on month increase in the CPI.

Will we see dramatic increases in prices and a return of consumer price inflation in a big way? It is far too soon to tell. If the strike is resolved in a few days the effects will obviously be less than if the strike drags on for several weeks.

Will we see dramatic increases in prices across the board? Yes and no. Not all goods are shipped primarily via the eastern ports and so not all goods are going to be equally bottlenecked. We will not see uniform dislocations among all goods even if the strike drags on for several weeks.

Will the inflation data that emerges in November and beyond dissuade the Fed from further rate cuts? Quite possibly. The greater the impact and the higher the inflation shock the less likely it is the Fed will cut in November.

At this juncture, no matter the outcome to the strike, we are on course to see some inflation increase in October. Depending on what other influences emerge, we may see a significant amount of inflation increase in October.

Corporate media might try to downplay the inflationary impacts of the strike, and Wall Street will no doubt continue to hope for another reduction in the federal funds rate, but be certain of this much fallout from this strike:

Inflation is coming.

Hypothetical for you. Supposing the strike lasts until Christmas or even beyond into first 1/2 of 2025. In your opinion would that cause potentially enough stress in the system, via either inflation to make the government discuss "protecting" private pensions, etc by transferring into government bonds or some such bond ? Ie protect the forced savings of the average workers, etc. Speculation I know but I'm following a trail of other signals as well, so I'm investigating a pattern I'm noticing.😉

Thanks for the helpful pricing scenarios, Peter. Politically, trump needs to hammer home that Harris ALLOWED this inflation to happen. Even more importantly, he needs to access which scarce items are going to affect voters’ holiday plans. Your kids can’t get this year’s most desirable toys for Christmas? You’ll gain back all the weight you lost because you can’t get Ozembic, and that means you’ll have to starve yourself this holiday season? Which now-unattainable or impossibly expensive items will trigger rage against HarrIs and a vote for Trump?