As the Supreme Court finishes out the 2019-2020 term, it ruled on two small, barely noticed cases from the 2016 Presidential election. Indeed, the cases were noteworthy more for having received a unanimous vote from the Court than from any contentious debate over finer points of Constitutional law, and from the fact that the two cases were heard separately, as Justice Sotomayor had to recuse herself from one case but not the other.

However seemingly minor the cases appear to be, arising from two lawsuits over a state's authority to bind Presidential electors to a specific voting preference, the ruling reiterates an important aspect of Presidential elections that has all but disappeared from political discourse and debate in this country: A President is elected not by the people but by the States. In issuing their per curiam opinion in Chiafalo, et al, v Washington (591 U.S. ___ (2020), Docket 19-465), the Supreme Court laid down a legal reminder of the Constitutional order of things.

Ironically, reiterating that Constitutional principle was probably not uppermost in Justice Kagan's mind as she wrote for the Court. As Justice Thomas pointed out in his concurring opinion, Kagan's per curiam opinion was full of logical, Constitutional, and semantic flaws, yet still managed to achieve, quite by accident, a Constitutionally correct result. While Kagan misreads Article 2 of the Constitution as granting authority towards the states, the end result of the states possessing authority over Presidential electors is Constitutionally sound.

Justice Kagan: Taking The Long And Winding Road

Justice Kagan begins her opinion with a factual mis-statement about Presidential elections, which she immediately mostly corrects:

Every four years, millions of Americans cast a ballot for a presidential candidate. Their votes, though, actually go toward selecting members of the Electoral College, whom each State appoints based on the popular returns. Those few “electors” then choose the President.

While it stands at odds with the popular perception about Presidential elections, the first statement is simply not true. While the Presidential candidates are the names that appear on the ballot come election time, the votes cast are never for the candidate but rather for that candidates' slate of Electoral College Electors. Only the Electoral College ever actually votes on whom the next President should be, as is clearly laid out in the Twelfth Amendment.

The Electors shall meet in their respective states, and vote by ballot for President and Vice-President, one of whom, at least, shall not be an inhabitant of the same state with themselves; they shall name in their ballots the person voted for as President, and in distinct ballots the person voted for as Vice-President, and they shall make distinct lists of all persons voted for as President, and of all persons voted for as Vice-President and of the number of votes for each, which lists they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the seat of the government of the United States, directed to the President of the Senate;

The Electoral College votes for President and Vice President are the only actual ballots ever cast for either office. The referendum polls conducted by each state are merely the generally accepted means by which a state's electors are chosen.

After a lengthy but superficial--and wholly irrelevant--review of the history behind the Twelfth Amendment, Justice Kagan in an almost offhand fashion makes a crucial observation about Presidential elections and the Electoral College:

Within a few decades, the party system also became the means of translating popular preferences within each State into Electoral College ballots. In the Nation’s earliest elections, state legislatures mostly picked the electors, with the majority party sending a delegation of its choice to the Electoral College.

In other words, in the early Presidential elections there was no popular vote. The selection of Presidential electors was a task for the State legislature. South Carolina would not hold a popular vote for President until after the Civil War.

Justice Kagan ventures into some further factual errancy with her summation of Presidential voting through American history:

At first, citizens voted for a slate of electors put forward by a political party, expecting that the winning slate would vote for its party’s presidential (and vice presidential) nominee in the Electoral College. By the early 20th century, citizens in most States voted for the presidential candidate himself; ballots increasingly did not even list the electors.

This is at best an oversimplification of Presidential balloting, and at worst egregiously sloppy mis-statement. While the solidification of America's two-party system after the Civil War rendered the selection of a President to a choice between the Democratic and Republican nominees, and while ballots today mention only the Presidential candidates themselves, the structure of the Presidential election statutes in the several states still makes the vote for a slate of electors to the Electoral College.

In order to obtain a position on a state's ballot, a candidate (or, more properly, the candidate's political party) has to provide to the state the party's slate of electors. This certainly is the case in the State of Texas (Texas Election Code, Chapter 192, Subchapter B, Section 31(2)(B) and Section 32(2)). Moreover, the Texas Election Code specifically states that the votes are for the electors in Section 35:

A vote for a presidential candidate and the candidate's running mate shall be counted as a vote for the corresponding presidential elector candidates.

In other words, voters elect presidential electors.

Kagan continues to mis-state this aspect of Presidential elections, however, asserting that appointment is an event that takes place after voting:

After the popular vote was counted, States appointed the electors chosen by the party whose presidential nominee had won statewide, again expecting that they would vote for that candidate in the Electoral College.

This is simply not a fair reading of at least the Texas Election Code.

However, despite Kagan's numerous flaws of construction and fact, her erroneous reasoning does lead to a legal and factual reality: Presidential elections are a state action, not a popular one. Thus, even though her opinion is flawed, her conclusion is not.

Justice Thomas: Short and To the Point

With his usual clarity, Justice Clarence Thomas, in drafting a concurring opinion, sweeps away Justice Kagan's fallacious reasoning and establishes a more defensible Constitutional logic within the first paragraph of his concurrence:

The Court correctly determines that States have the power to require Presidential electors to vote for the candidate chosen by the people of the State. I disagree, however, with its attempt to base that power on Article II. In my view, the Constitution is silent on States' authority to bind electors in voting. I would resolve this case by simply recognizing that "[a]ll powers that the Constitution neither delegates to the Federal Government nor prohibits to the States are controlled by the people of each State."

Justice Thomas viewed the essential question of the case before the Court as one of states rights, and as the Constitution is silent as to the qualifications of electors (beyond disqualifying current members of Congress and others holding an office of trust or profit under the United States), the default presumption of the Constitution is that states are empowered to qualify and appoint Presidential electors as they see fit. Thomas correctly notes that the Constitution itself mandates this approach through the language of the Tenth Amendment:

This structural principle is explicitly enshrined in the Tenth Amendment. That Amendment states that "[t]he powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people." As Justice Story explained, "[t]his amendment is a mere affirmation of what, upon any just reasoning, is a necessary rule of interpreting the constitution. Being an instrument of limited and enumerated powers, it follows irresistibly, that what is not conferred, is withheld, and belongs to the state authorities."

The one point of reasoning on which Thomas and Kagan agree is that Presidential elections are an area of governance in which the States hold sovereignty. More precisely it belongs to the States as organized polities, acting through their respective legislatures. As the Constitution does not claim any regulatory power for the Federal government over the appointment of Electors, the states remain at liberty to choose whether to bind Electors to the outcome of the popular referendum vote in each state.

Justice Thomas goes on to point out that, while the Constitution does not claim any regulatory oversight of the appointment or conduct of Presidential Electors, both the manner of the appointment and the conduct of the Electors themselves must broadly conform to the mandates that do exist in the Constitution.

Of course, the powers reserved to the States concerning Presidential electors cannot "be exercised in such a way as to violate express constitutional commands." Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U. S. 23, 29 (1968). That is, powers related to electors reside with States to the extent that the Constitution does not remove or restrict that power. Thus, to invalidate a state law, there must be "something in the Federal Constitution that deprives the [States of] the power to enact such [a] measur[e]."

As Justice Thomas then concludes that the Constitution includes no such mandate which either compels Elector independence or prevents the states from binding the Electors to the states' respective popular votes.

While Thomas' concurrence differs dramatically from Justice Kagan's opinion in the substance of its reasoning, where it coincides with Kagan's opinion is the centrality of the several states and not simply the people of the states to Presidential elections. Without giving the principle any especial emphasis, both Justice Thomas and Justice Kagan acknowledge that Presidential elections are a matter for the states as distinct polities, rather than for the people of the United States as a whole.

The Constitution: The States Elect The President

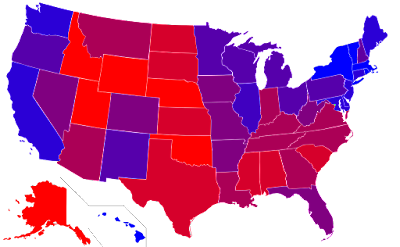

That the states and not the people of the United States choose the President every four years might seem to be a splitting of Constitutional hairs, but the Electoral College is an essential guarantor of federalism within the governance of the United States. State sovereignty in Presidential elections ensures state sovereignty overall, and acts to check the power of the Federal government.

A quick reading of Federalist 68 confirms the primacy of the states in Presidential elections. As Alexander Hamilton points out, the mechanism of the Electoral College compels the selection of a President able to speak to the concerns and desires of all of the states, and not merely a few influential interests.

The process of election affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications. Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union, or of so considerable a portion of it as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States. It will not be too strong to say, that there will be a constant probability of seeing the station filled by characters pre-eminent for ability and virtue. And this will be thought no inconsiderable recommendation of the Constitution, by those who are able to estimate the share which the executive in every government must necessarily have in its good or ill administration. Though we cannot acquiesce in the political heresy of the poet who says: "For forms of government let fools contest That which is best administered is best,'' yet we may safely pronounce, that the true test of a good government is its aptitude and tendency to produce a good administration.

By ensuring the states as organized polities have a role in the election of a President, the Electoral College thus acts to prevent the states from being permanently subordinated to the Federal government.

The Electoral College is also a constant debunking of the myth within the legacy media of the "national popular vote" for President. Simply put, the Electoral College is proof the "national popular vote" does not exist--and cannot exist. The "national popular vote" canard was given particular prominence, one will recall, in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 Presidential election, when even presumed Constitutional scholars such as Lawrence Lessig erroneously asserted a fundamental illegitimacy in an Electoral College outcome that did not comport to this non-existent "national popular vote."

The Chiafolo decision, without taking the issue on directly, establishes clear legal precedent against a "national popular vote" as a concept, and undermines the ongoing efforts of some to explicitly align the Electoral College outcome with this fiction. In both Kagan's per curiam opinion and Thomas' concurrence, a clear jurisprudential marker is laid down confirming that Presidential elections are indirect elections, and that in every state one is not voting for a Presidential candidate per se, but is instead voting for that candidate's chosen slate of electors. As the Presidential ballot in each state is clearly established as a state election for a state office--that of Presidential Elector--the notion of a "national popular vote" can be immediately seen as not merely a fiction but an outright impossibility.

One inevitable consequence of Chiafolo is that any arrangement among the states to align their Electoral College votes with this fictional "national popular vote" is a redefinition of the role of the Presidential Elector away from the state office defined in the Constitution. By affirming that Presidential votes are in fact votes for Presidential Electors, the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact becomes a mechanism whereby people in various states are in effect electing Presidential Electors for other states. Far from being merely a compact among states--which in all cases requires the consent of Congress per Article 1 Section 10--such an arrangement is a new political alliance which is categorically forbidden in Clause 1 of that same section of the Constitution:

No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation; grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal; coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts, or grant any Title of Nobility.

For the voters of one state to choose electors for another state would be as irrational and as Constitutionally impermissible as voters in one state electing Congressmen and Senators for another state.

All States Matter

As Thomas noted in his dissent from 1995's US Term Limits, Inc. v Thornton (514 US 779) the essence of federalism within the Constitutional order of things is the power of the people within each of the several states, not the people as an amorphous whole across the entirety of the United States:

Our system of government rests on one overriding principle: All power stems from the consent of the people. To phrase the principle in this way, however, is to be imprecise about something important to the notion of "reserved" powers. The ultimate source of the Constitution's authority is the consent of the people of each individual State, not the consent of the undifferentiated people of the Nation as a whole.

The Electoral College system is an important expression of this relevance of the several states. By requiring the states to select Presidential Electors, the Constitution makes permanent the proposition that the several states are sovereign entities. Making the states acting as sovereign entities central to the selection of the President makes the quadrennial election of the President a recurring affirmation of the Constitutional structure best articulated in Federalist 45, that, beyond select powers ceded to the national government, the states themselves retained their fundamental sovereignty:

The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the federal government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State governments are numerous and indefinite.

The Electoral College ensures and reminds us that all of the states are important, and that all of the states matter.

While a seemingly small, trivial, and even trite case, Chiafolo is an important reminder that our country is as it has always been--a federation of sovereign states united by common fidelity to the Constitution of The United States.