Mexico Is Merely Doing Less Badly Than China

Import And Export Weaknesses Are Still Global

Perhaps the biggest economic news this week has been the revelation that, in 2023, Mexico, not China, was the top importer of goods into the United States.

After 17 years as the top source of imported goods in the United States, China will likely move into second place for 2023, ceding the first position to Mexico, according to data released by the U.S. Commerce Department this week.

The shift is the result of a yearslong trend that has seen a gradual decline in China's share of the U.S. import market, driven primarily by continued U.S. tariffs on a broad array of Chinese goods. However, other contributing factors include a broader reshuffling of global supply chains in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic and a push by the U.S. to diversify sources of important imports away from China and toward geopolitical allies, a process sometimes known as "friendshoring."

Indeed, the corporate media rather happily spins this as a triumph for Mexico and Mexican manufacturing especially.

In the depths of the pandemic, as global supply chains buckled and the cost of shipping a container to China soared nearly twentyfold, Marco Villarreal spied an opportunity.

In 2021, Mr. Villarreal resigned as Caterpillar’s director general in Mexico and began nurturing ties with companies looking to shift manufacturing from China to Mexico. He found a client in Hisun, a Chinese producer of all-terrain vehicles, which hired Mr. Villarreal to establish a $152 million manufacturing site in Saltillo, an industrial hub in northern Mexico.

Mr. Villarreal said foreign companies, particularly those seeking to sell within North America, saw Mexico as a viable alternative to China for several reasons, including the simmering trade tensions between the United States and China.

“The stars are aligning for Mexico,” he said.

While there is a definite trade shift away from China, Mexico’s climb into the number one importer position is not entirely due to growth in Mexican imports into the US. Rather, the trend is more accurately depicted as Mexican imports have declined less than Chinese imports.

Trade with the US is still softening, but at different rates for different countries. Trade with China is decelerating the fastest among the United States’ principal trading partners, and so it has fallen out of the top slot.

In other words, China is still leading the global race to the bottom.

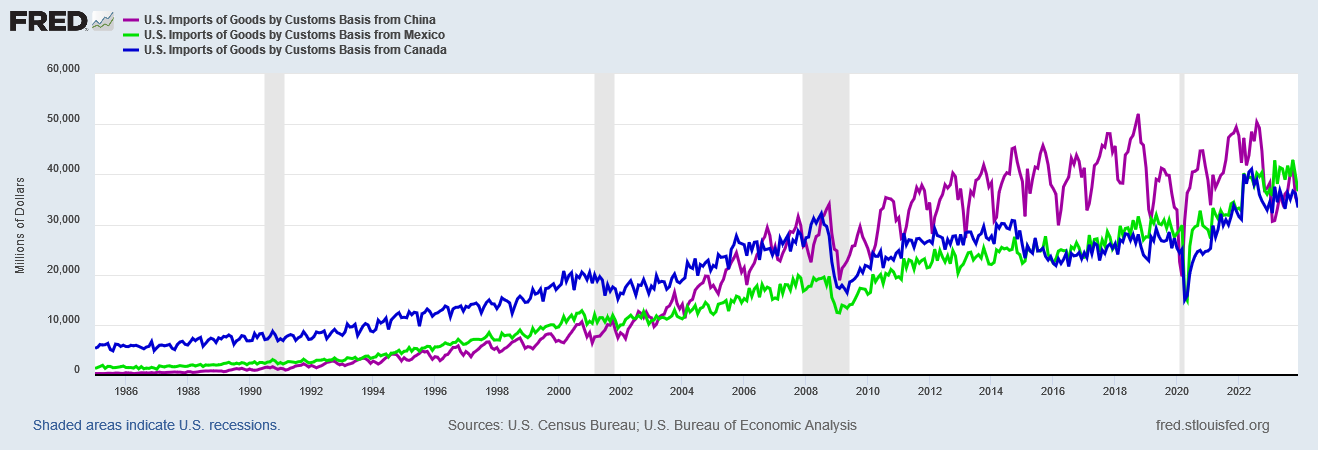

A bit of context is helpful to understand the shifting trade flows at play. For a number of years, the three principal sources of imports into the United States have been China, Mexico, and Canada. So significant are these trading partners that there is a major drop-off from the number three slot (currently held by Canada) and the next four importing nations.

However, China’s trade dominance is relatively recent, with Canada having been the number one importer up until the summer of 2006. China did not establish its dominant trade position with the US until after the 2008-2009 recession.

It was also during those years following the Great Financial Crisis that Mexico overtook Canada in terms of total value of US imports.

We should also note that, as a result of President Trump’s trade policies (read “trade war”) with China, China’s imports to the US declined significantly during 2018-2019, although China remained in the number one importer slot.

In the aftermath of the Pandemic Panic Recession, China’s imports to the US recovered almost to the 2018 peak, before declining again.

In fact, for most of The Biden Regime, imports from China increased, and only began a major decline in July of 2022.

One point that should not be overlooked: Canada imports less into the US than China, but only just. It would not take a radical departure from the prevailing trends either for China imports or Canada imports for China to fall behind Canada into the number three position—which in fact happened from February through June of last year. If Canada’s export-oriented economic sectors pick up before China’s economy, and if US tariffs on China trade remain in place, China could very easily wind up in the number three position more or less permanently in the very near future.

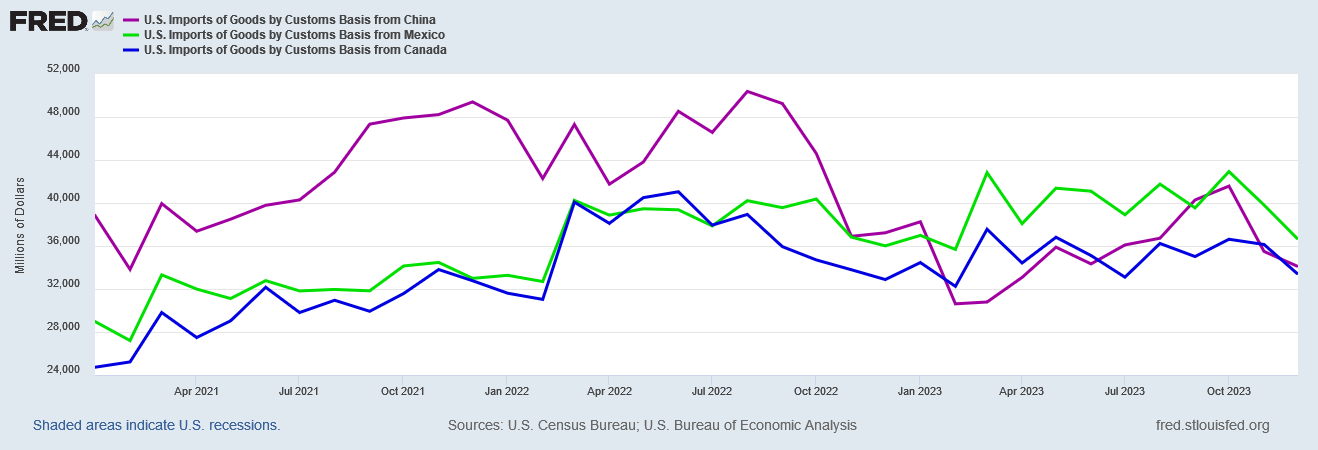

However, if we look closely at the import numbers for Mexico and Canada, we see that there is not a significant uptick in imports Quite the opposite: After a surge of imports in early 2021, the growth in imports has tapered off significantly, and actually declined not just for China but for Canada, with Mexico seeing minimal import growth in recent periods.

This is significantly different from the Trump pre-pandemic years, when China’s imports to the US declined while Canada and Mexico held up far better.

As much as the media likes to use the word “surge” to describe Mexico’s ascendancy to the top importer slot, in reality there has been no “surge” of imports at all by any country.

Quite the contrary: Canadian imports peaked before China imports did, and Mexican imports have remained relatively constant since March of 2022.

Even looking at just China imports, we see that, while there has been significant volatility (in part because the data is not seasonally adjusted), the longer term trend has been only slightly down.

China imports have declined most sharply from the summer of 2022, but that decline comes against a backdrop of more rises than falls from 2021 onward.

However, this relatively mild decline across the board on imports does not mean there are not trade shifts unfolding. At the same time that China imports have started declining only from the summer of 2022 onward, US exports have been increasing especially to Canada and Mexico.

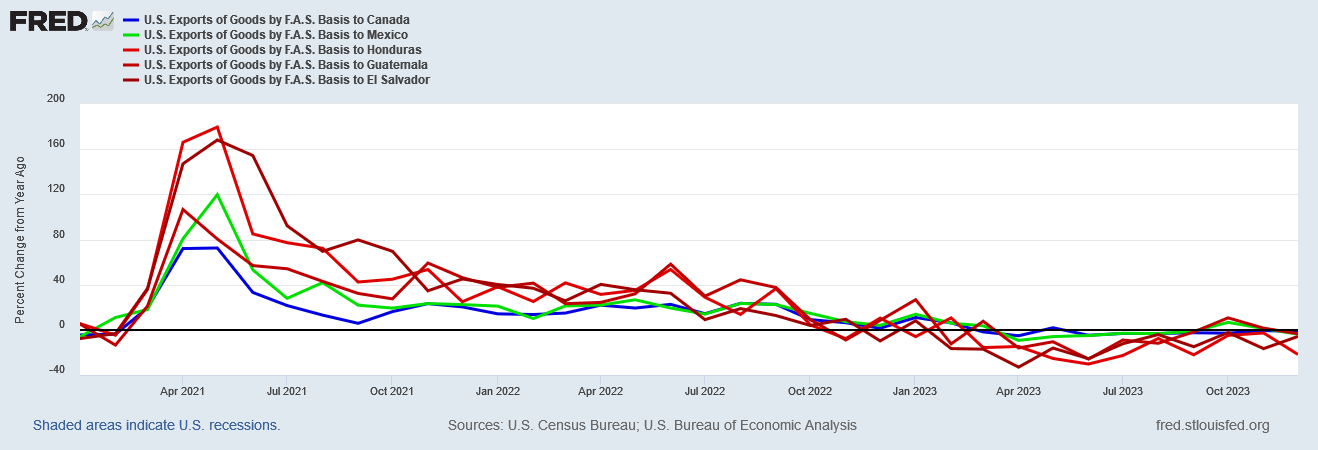

Indeed, US exports to Canada and Mexico have been steadily increasing relative to America’s other principal trading partners for decades—outpacing even China.

Exports to Canada and Mexico did especially well relative to China during President Trump’s first three years in office.

However, even at that, US exports began to soften and even decline from the spring of 2018 onward.

This was a clear case of China falling farther and faster than the other principal trading partners.

During The Biden Regime, even Canadian and Mexican exports have been largely on a decelerating trend after an initial burst of growth in 2021.

Whether we are talking imports or exports, the overall trajectory of either within the US economy has been one of weakeness, deceleration, and decline.

Nor is this a phenemonon isolated to just China, Canada, and Mexico. While US trade with Latin America is nowhere near the size of trade with China, Canada, and Mexico, the trends on both imports and exports have been relatively similar.

After a surge of growth during 2021, even to Latin America the prevailing trend since 2021 has been, once again, weakness, deceleration, and decline.

While it would be disingenuous to extrapolate US imports and exports to a projection of the entire global economy, these downward trends in both imports and exports, both among the principal US trading partners and US regional trading partners, unequivocally point not just to a softening and contracting US economy, but also to softening and weakening economies among US trading partners. When there is neither import growth nor export growth, economic growth immediately becomes suspect.

It is true that Mexico has moved into the top importer slot among US trading partners. It is true that China and Canada are currently neck and neck for which one comes in second and which one comes in third among importers.

Yet it is also true that, overall, import levels with all three countries are either largely flat or are decreasing. It is also true that the US is seeing similar declines among regional trading partners within Latin America. It is also true that export levels are weakening and declining as well.

Mexico is now the top US importer, but not because of any “surge” in Mexican imports. Mexico has moved into the top slot simply because its import levels have declined more slowly than China’s or Canada’s. China might be leading the global race to the bottom, but we should not forget that there demonstrably is a race to the bottom occurring.

A ‘race to the bottom’ says it all.

The older I get, the more I notice that KINETICS is instrumental in every process. (For those readers who are liberal-arts grads, kinetics is the RATE of reaction, and is usually determined by using differential calculus - so now you know what calculus is for!) If a weather system spins just a tiny bit slower, the weather ends up different from what was forecast, hundreds of miles away - the RATE of that spinning is crucial to the forecast. If the chemical bonding rate between two elements in a magma happens just a little bit faster than the bonding rate of two other elements, you end up with different minerals crystallizing from the magma than if the RATE of chemical reactions was different.

And this importance of RATE is crucial in macroeconomics as well. If China declines faster relative to other economies, if Mexico’s economy grows faster than Nicaragua’s, while 200 other national economies are also growing at different rates relative to each other, you get different international economic results. To make things even more interesting, most of the rates are constantly changing! This makes it almost impossible to predict the economic future.

Peter’s excellent graphs and data show us, amongst other things, the rates of economic processes. China IS declining. Now it’s going to be fascinating to watch the mash-up of the relative rates in different economies. Place your bets!

https://open.substack.com/pub/peternavarro/p/onward-and-upward-past-5000-as-communist?r=z3pgv&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post

Peter, the Authorities have denied Navarro his request to remain free awaiting appeal - it looks like he is actually going to prison!

Be careful out there; apparently neither logic nor law can save you. If anyone ever calls you ‘paranoid’, they’re wrong!