Oil Prices Prove Once Again You Can't Push A String

When Demand Is Soft No Supplier Has Leverage

When OPEC+ announced their surprise production cuts at the beginning of April, a number of analysts immediately jumped back on the “$100 a barrel” bandwagon.

Oil has the potential to reach $100 a barrel by late this quarter after OPEC+ announced steep crude output cuts, according to Amrita Sen, the chief oil analyst at Energy Aspects.

Her view has been that the second half of the year was going to “very bullish,” pushing oil to $100 as long as the global economy was resilient. Now, that move higher could happen sooner, including late in the second quarter, she said in an interview on Bloomberg Television.

Nor was Amrita Sen alone in this thinking. A prevailing viewpoint is that OPEC+ is flexing its market-making muscles with this production cut.

"One thing is for certain, OPEC is in control and driving price and U.S. shale is no longer viewed as the marginal producer," said James Mick, senior portfolio manager at Tortoise Capital Advisors.

"OPEC wants and needs a higher price, and they are back in the driver's seat to obtaining their wishes."

This viewpoint is bolstered somewhat by the fact that, immediately after announcing the production cuts, Saudi Arabia announced a rate increase in oil sold to Asian markets.

Saudi Arabia, the world's top oil exporter, has raised the prices of its flagship crude for Asian buyers for the third straight month.

The official selling price (OSP) for May-loading Arab Light to Asia was raised by 30 cents a barrel from April to $2.80 a barrel over Oman/Dubai quotes.

Similar rate hikes were imposed for Arab Medium and Arab Heavy blends as well.

Similarly, Amena Bakr of Energy Intelligence tweeted out that OPEC’s production cuts were strategic.

(Note: Substack and Twitter no longer play nice with each other so I am unable to embed tweets as I have in the past. I still link to them, however)

Her thesis is that a production cut was not necessary given that oil prices internationally were already at or near $80/bbl.

Yet the price movements since the production cut was announced do not speak to much in the way of market making power. If anything, the production cut appears to have stopped a price rise in oil dead in its tracks. The prices the benchmark blends are command in the open market have changed little since the day after the initial price increase.

If we look at two of the primary oil price benchmark blends, Brent Crude and West Texas Intermediate, we immediately see the plateau beginning right after the production cuts were announced.

Note that between January 13 and March 10, oil prices were largely stable, although trading in a somwhat wide band around $83/bbl for Brent Crude and around $77/bbl for West Texas Intermediate.

However, as we can see from looking at just the past 25 days, the upward trend in spot oil prices comes to around latest prices as of April 6 for both blends.

Much like the Red Queen in Through The Looking Glass, OPEC’s cuts at this juncture look an awful lot like running and running just to end up staying where you are. Cutting production and causing a stir in the financial media just to end up a week later with roughly the same price OPEC might have had otherwise is a curious display of market muscle or strategic thinking.

Nor is this plateau effect confined to Brent Crude and WTI. Both the DME Oman and Dubai blends—the two benchmark crudes that Saudi Arabia’s ARAMCO uses to calculate its oil price quotes to markets such as Asia—display the same phenomenon, as does Saudi Arabia’s Arab Light, Medium, and Heavy Blends.

While final conclusions might still be somewhat premature after a single week, it’s hard to see how a 1 million bpd+ oil cut is justified if oil prices only move up a few dollars. Barring a significant change in oil markets, however, OPEC conceivably has already received all the pricing benefit it is likely to get from the production cut.

Certainly if we look at the historical chart for either Brent or WTI, we see that a plateau is more likely the precursor to a price decline than a price increase.

Depending on how long the current plateau holds, the next significant price move in oil may be to trend down yet again.

Did OPEC mis-read the market? Certainly that is one possibility. However, if we consider the ramifications of a global recession on oil demand, the production cut may very well have been defensive in nature, and not merely a display of market making muscle.

Some analysts contend that an oil glut exists in the global oil market, which is holding down prices all around.

And now one analyst has predicted that the cuts will eliminate the huge surplus that had built up in the oil markets. Commodity experts at Standard Chartered have reported that a large oil surplus started building in late 2022 and spilled over into the first quarter of the current year. The analysts estimate that current oil inventories are 200 million barrels higher than at the start of 2022 and a good 268 million barrels higher than the June 2022 minimum.

Additionally, Pavel Molchanov, managing director for private investment bank Raymond James, suggests that even if $100/bbl is reached, it would not be the long-term equilibrium price range.

However, while $100 per barrel may be within the horizon, the higher price point may not stay for long, said Molchanov, adding that it’s not going to be “the permanent plateau.”

“In the long run, prices could be more kind of in line with where we are today” — in the region of about $80 to $90 or so, he said.

If that assessment is accurate, OPEC presumably is planning oil production cuts that would be almost precisely calibrated to the actual state of oil demand so as to establish almost immediately the equilibrium price. That would be either the most amazing stroke of luck or an impressive bit of market and economic analysis by OPEC.

Yet it was just in January that OPEC cut its prices to Asian markets in response to weak oil demand, particularly from that region.

Saudi Arabia cut oil prices for its main market of Asia and for Europe, signaling that demand remains sluggish as economies slow and coronavirus cases in China surge.

A price cut followed by a production cut is not exactly a vote of confidence in future sales, to Asia or to anywhere. If anything, the production cut comes as an acknowledgement that sales will be lacking for the foreseeable future, particularly from China.

While there are signs that China’s overall oil demand is rising, there are also many signs that China’s overall economic “reopening” is not quite as dramatic as many have hoped.

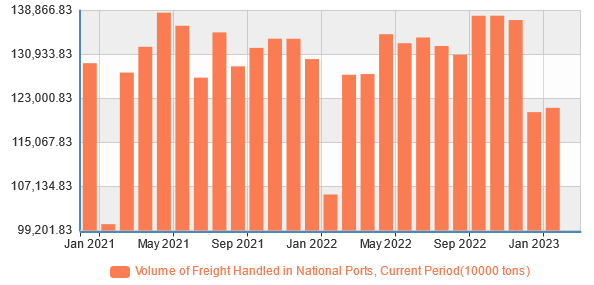

Freight traffic did not actually begin to recover until February (China’s data for March is largely not yet available).

At China’s ports, freight volumes dropped at the end of 2022 and have yet to recover.

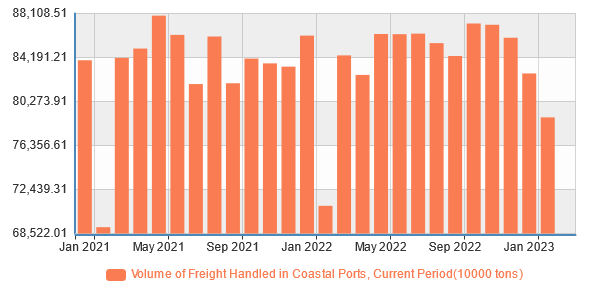

The coastal ports, where China’s exports are handled, have fared no better.

Without meaningful increases in both interior freight traffic and export traffic, how much actual demand China will have for oil is problematic, which makes the projections for increased production and throughput by Sinopec, China’s leading oil refiner, dubious at best.

Sinopec, China's leading consumer of imported crude, has set a target for their processing capacity in 2023. The company is aiming to process 250 million metric tonnes, or 5.03 million barrels per day (b/d) - an increase of 3.2% from the 4.88 million b/d they realized in 2022 and lower than the 5.14 million b/d processed in 2021.

Nor is China alone in the Asian economic doldrums.

Certainly India’s economy appears to be in less than rude health. Unemployment has been rising on the subcontinent for the past three months, and has been stubbornly above 7% for the past six months.

Headline labour market metrics of March 2023 turned out to be disappointing. The unemployment rate climbed from 7.5 per cent in February 2023 to 7.8 per cent in March; the labour participation rate fell from 39.9 per cent to 39.8 per cent and the employment rate dropped from 36.9 per cent to 36.7 per cent in the same months.

Electricity production in that country—a common high-frequency indicator for the health of an economy—plummeted during COVID and has remained low ever since.

Meanwhile, India’s foreign trade has been steadily shrinking since last summer.

India’s merchandise exports have been on a declining trend since its peak in March 2022. Exports have fallen from USD 44.5 billion in March 2022 to USD 33.9 billion in February 2023. As a result, exports in February 2023 were 8.8 per cent lower than they were in February 2022. The decline in February was on account of a fall in POL as well as non-POL exports.

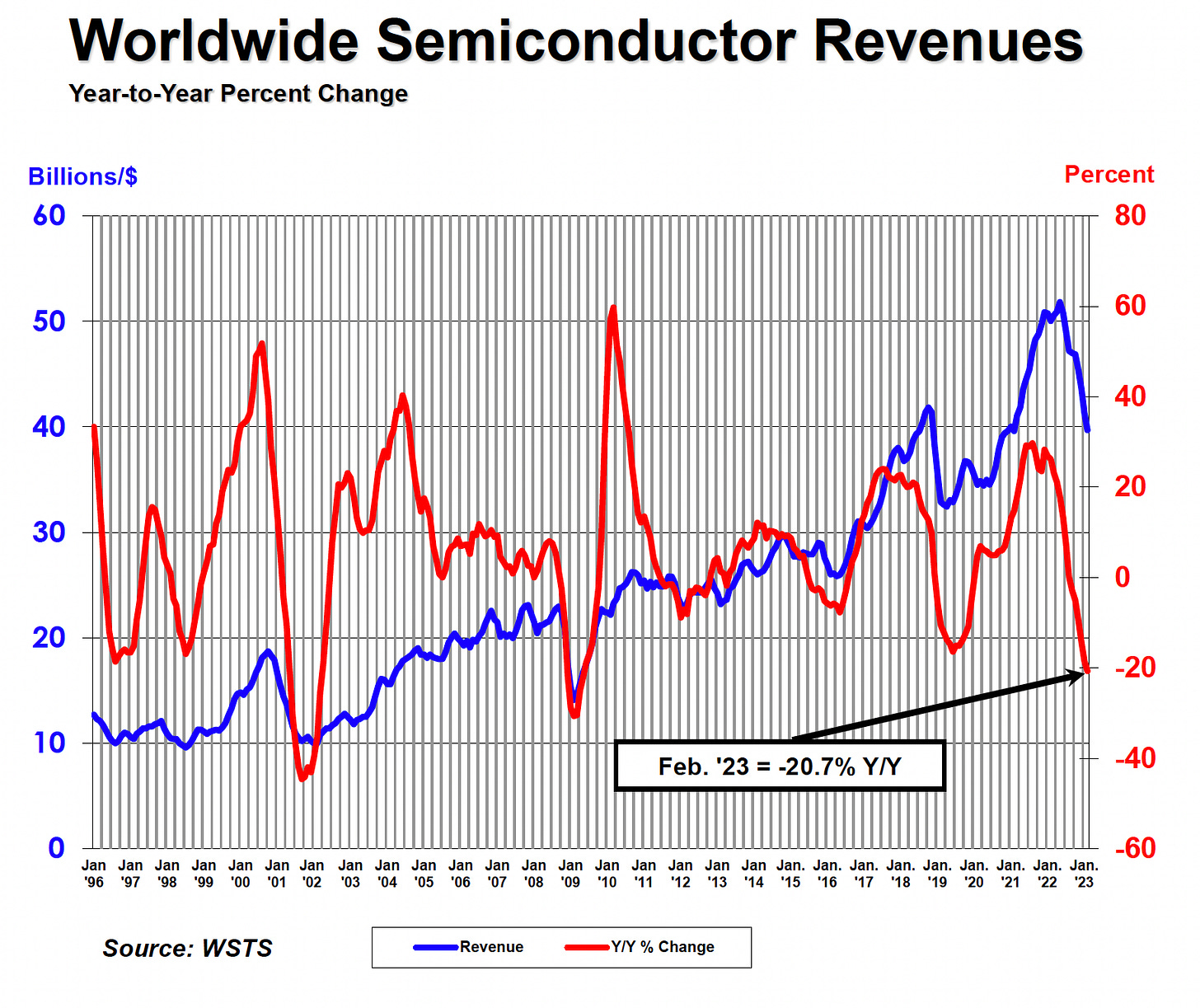

Moreover, semiconductor sales during February across the Asia Pacific region dropped year on year by 22.1%, the second largest regional decline behind China’s 34%.

The Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) today announced global semiconductor industry sales totaled $39.7 billion during the month of February 2023, a decrease of 4.0% compared to the January 2023 total of $41.3 billion and 20.7% less than the February 2022 total of $50.0 billion. Monthly sales are compiled by the World Semiconductor Trade Statistics (WSTS) organization and represent a three-month moving average. SIA represents 99% of the U.S. semiconductor industry by revenue and nearly two-thirds of non-U.S. chip firms.

Semiconductor sales globally have been so bad that Samsung recently announced significant production cuts after profits virtually collapsed for the Korean chipmaker.

Samsung Electronics said Friday it was cutting its chip production to a “meaningful level” after reporting a worse-than-expected 96 percent plunge in its quarterly operating profit estimate amid the global chip downturn.

“We’re adjusting to lower memory production to a meaningful level centering on products that have secured enough inventory to respond to future demand, in addition to optimizing line operations that are already underway,” the company said in a statement.

A 96% drop in quarterly profit at a flagship company in a mainstay of the modern economy is a performance more in line with an economic depression than economic recovery.

Nor is the US without a constant cacophony of negative economic indicators, the most recent being the Commerce Department’s reporting that factory orders declined 0.7% in February, following a record 2.1% plunge in January.

New orders for manufactured goods in February, down three of the last four months, decreased $3.9 billion or 0.7 percent to $536.4 billion, the U.S. Census Bureau reported today. This followed a 2.1 percent January decrease. Shipments, also down three of the last four months, decreased $2.8 billion or 0.5 percent to $542.8 billion. This followed a 0.3 percent January increase. Unfilled orders, down following twenty-nine consecutive monthly increases, decreased $1.1 billion or 0.1 percent to $1,155.6 billion. This followed a virtually unchanged January increase. The unfilled orders-to-shipments ratio was 6.10, up from 6.09 in January. Inventories, down two consecutive months, decreased $0.8 billion or 0.1 percent to

$806.3 billion. This followed a 0.1 percent January decrease. The inventories-to-shipments ratio was 1.49, up from 1.48 in January.

Not to be outdone as a harbinger of bad economic news, the housing sector in the US is continues to experience a collapse of housing prices.

Existing home prices fell 12% to $363,000 in February from $413,800 last June.

Don’t expected a rebound soon, say analysts from Moody’s Investors Service. “Likely increases in unemployment and a U.S. recession later this year will additionally pressure sales and prices,” they wrote in a report.

The sures sign of global economic recession is this steady “drip, drip, drip” of bad economic news and worse economic data.

With signs of global economic contraction quite literally everywhere, in every part of the globe, OPEC+ can certainly be forgiven for thinking that oil production might not be quite as needed in the coming months and perhaps years as many have hoped (and continue to hope).

If the current pricing trends among leading benchmark crude oil blends hold, oil prices will have proven once again that you cannot push a string. Production cuts will not ever result in increased demand; at most they align future output with future demand. By their very nature that is all they can hope to accomplish.

This makes pontifications such as Amena Bakr’s only half right. OPEC+’s strategy very much is about price, but it is also about price on a longer horizon. Production cuts in the face of declining global demand in just about every major economic sector and across all parts of the globe arguably are a reasoned response to economic recession. If current prices and production levels are producing a glut of oil on the world market, then less production is absolutely in order. The centrality of oil to so much of the modern economy is such that a glut at any price inherently a symptom of a lack of demand at all prices—which means that once a glut forms a price cut alone will not clear it. A glut of oil means production is outpacing demand at all levels, and if demand is not showing any indications of imminent recovery, the only means left to rebalance supply and demand is to reduce production—which is exactly what OPEC+ has done.

OPEC+’s production cuts are looking more and more like a strategic retreat from a global oil market that is not showing any signs of robust growth either now or in the near future. It is the inevitable consequence of a global recession that continues to get worse even as the “experts” strive ever harder to deny its existence.