One Country's Food Price Inflation Is Another Country's Food Insecurity

The Dark Subtext Of Inflation: Hunger

As I observed in last week’s article assessing the dismal state of inflation in the US, there was a disturbing artifact within the CPI sub-component of food prices: the cost of eating at home is rising faster than the cost of eating out.

When we look at food price inflation over the past 20 years, this inflation inversion only happens sporadically. The long term trend has generally been that is it cheaper to eat at home than it is to eat out. That dynamic is changing.

This unusual inversion of the normal relationship between these two food price sub-components raises some disturbing questions regarding food price inflation and the potential for that inflation to become actual food insecurity.

Does this inversion indicate a future rise in food insecurity within the US? The possibility cannot be overlooked. As the prices of staple goods such as eggs, milk, chicken and beef rise, the capacity of consumers particularly in the lower income brackets to purchase enough food steadily declines. If the inflation trend continues, the number of Americans unable to afford adequate food is almost certain to increase.

Even as Americans grapple with the increasing challenge of putting enough food on the table, we should pause to realize that, in many parts of the world, that challenge is far greater, and the outlook is far more dire.

The consequences of inflation are not simply that goods and services are more expensive. Particularly for those near the lower end of the economic spectrum, the very necessities of life become increasingly dear—and sometimes unobtainable.

Food Price Inflation Is A Major Factor In Overall Inflation

The sobering reality for the United States is that food price inflation is, after energy items, the largest contributor to overall consumer price inflation.

After declining in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19-induced recession of 2020, in recent months food price inflation in the US has risen sharply, with food consumed at home incongruously increasing more than the cost of eating out.

Put simply, it is costing more and more just to eat.

At the same time, the pace of inflation is greater than the pace of wage growth in the United States.

Not only are people paying more to eat less, inflation means they are effectively earning less overall, making the impacts of food price inflation in the United States that much more pronounced. The higher food prices rise, the more difficult it becomes for people to afford food.

Food price inflation thus becomes food insecurity, thus becomes hunger—and in some countries, famine.

Part Of A Global Problem

As I have detailed previously, inflation is a problem around the world.

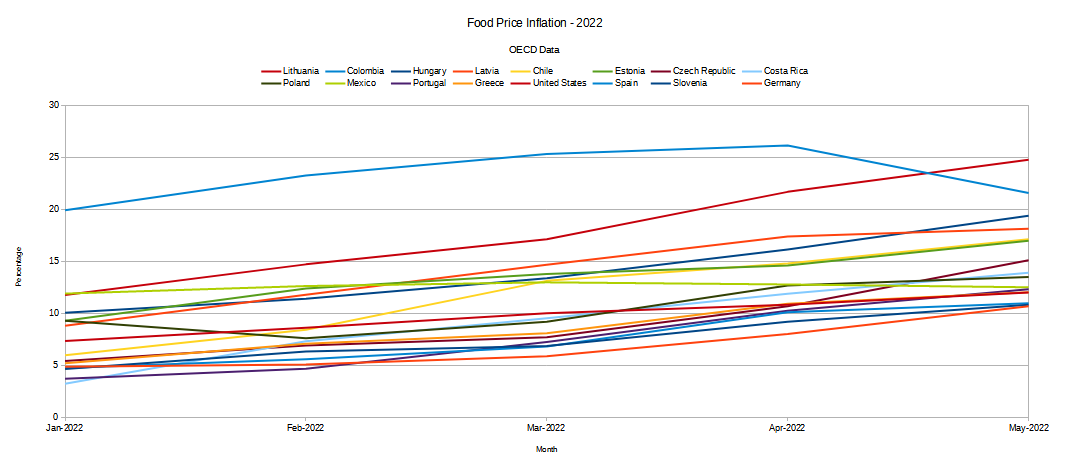

That is especially true for food price inflation. As data from the OECD illustrates, countries both richer and poorer are grappling with double-digit hikes in the price of a meal just this year alone.

While the United States is facing significant food price inflation, it is far from being at the top of the list—indeed, most other countries are faring far worse than the United States is.

Among developing countries especially, there is another word for food price inflation: hunger. According to the “Hunger Hotspots” report for May, issued jointly by the Food and Agriculture Organization and World Food Programmes agencies of the United Nations, approximately three quarters of a million people are already facing imminent hunger and potentially death from starvation.

According to the May 2022 Hunger Hotspots report, Ethiopia, Nigeria, South Sudan, and Yemen remain at ‘highest alert’ as hotspots with catastrophic conditions, and Afghanistan and Somalia are new entries to this worrisome class since the previous hotspots report in January 2022. These countries all have segments of the population facing IPC phase 5 ‘Catastrophe’ – or at risk of deterioration towards catastrophic conditions, with a total of 750,000 people already facing starvation and death in Ethiopia, Yemen, South Sudan, Somalia and Afghanistan.

As tracked by the FAO Food Price Index, food prices are rising globally and across all major food categories.

With cereals and various oils rising faster than overall food price inflation, people everywhere are under increasing pressure just to afford basic staples.

What’s Driving Food Price Inflation?

2022 is shaping up to be a veritable “perfect storm” of inflationary shocks and pressures, particularly on food prices.

Weather events are a significant driver of food price inflation. As the FAO/WFP Hunger Hotspot report details, a number of weather events have converged to produce significantly below-average harvests around the world.

Recurrent La Niña events since late 2020 have impacted agricultural activities, causing crop and livestock losses in many parts of the world including Afghanistan and Eastern Africa. The latest forecast indicates that La Niña conditions will continue through August–October 2022, with the probability of 58 percent and increasing slightly through the end of 2022. This could drive above-average rainfall across the Sahel and increase hurricane intensity in the Caribbean, and could, along with a forecast negative Indian Ocean Dipole, negatively affect the next Deyr/short rainy season in the Horn of Africa

Moreover, much of the globe is still grappling with the after-effects of the COVID-19 pandemic-inspired lockdowns, and the supply chain dislocations those lockdowns precipitated.

Economies of developing countries, many of which are still struggling with the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, could be further destabilized by the current slowdown of the global economic recovery. During the pandemic, some governments introduced significant fiscal stimuli to support household incomes and stabilize economies. These large public expenditures – during a period when tax receipts fell and foreign-exchange reserves declined – have increased the risk of debt distress. Moreover, the tightening of monetary policies in advanced economies to address the rapid increase of inflation rates have complicated access to credit and debt refinancing for developing economies since the end of 2021. This has led in some cases to the adoption of austerity policies that are having adverse impacts on household incomes. Furthermore, countries heavily reliant on global markets for hydrocarbons and food might have to pay larger amounts for their imports. This could lead to difficulties financing imports of essential needs and further increase the risk of currency depreciation and debt distress.

Not only are poorer harvests making food more scarce generally, economic conditions globally are threatening the abilities of countries to sustain necessary food imports.

This already bleak global situation has been further impacted by the Russo-Ukrainian War. Russia and Ukraine are both major food exporters as well as major exporters of fertilizers. The war has disrupted exports from both nations, threatening not only current food supplies but potentially next year’s food supply as well.

The war in Ukraine has already caused immense destruction of livelihoods, supply chains, infrastructure and contamination with explosive ordinances in the country, as well as large-scale displacement in the country and regionally. Ukraine being a major global food supplier, current supply disruptions are aggravating already high international prices, which complicates access to food and could result in localized shortages. With hostilities likely to persist in some regions and affect agricultural activities, together with supply chains disrupted, also food availability could become a challenge in Ukraine and globally if export supplies from other exporters fail to fill the gap.

Any one of these events would have significant impact on food prices and food availability around the world. Their convergence in 2022 is threatening to produce food shortages on a potentially Biblical scale.

At The Core Of Every Recession: Human Suffering

When discussing economic matters, it is distressingly easy to forget, amidst the myriad numbers and statistics that get tossed back and forth, that economic privation is, in every instance, an example of human suffering.

Recession, job loss, supply shocks—all these economic events translate into a basic scarcity of goods and services. There is simply less of everything available to buy—and sometimes there are simply no goods whatsoever.

Food price inflation is the grim reminder that food—a necessity for us all—is never immune from the impacts of economic contraction. The more that food prices rise, the fewer people there are who can afford to buy food—and thus the more people there are who are faced with the prospect of going hungry.

When the COVID lockdowns were first being implemented in 2020, I posed a simple question: “Who Counts The Deaths From Recession?”

Then, as now, the reality of recession is that it invariably produces its own mortality risks. Then, as now, a major component of that mortality risk globally is access to food—or the sudden lack of access to food.

It is far too soon to assess the ultimate consequences of food shortages, fertilizer shortages, and the prospect of reduced harvests even past 2023.

It is not too soon to assess that rampant food price inflation is already outright hunger for some people.

It is not too soon to assess that rampant food price inflation will result in a measure of death we would not otherwise witness.

It is not too soon to pause to remember that every recession by definition is an increase in human want.

The recession unfolding here in the United States is part of a global economic slowdown. Likewise, the food price inflation unfolding here in the United States is part of a global pattern of food price inflation. Food price inflation, producing food insecurity and ultimately hunger, is happening everywhere.

Such is the grim reality of the “interesting times” in which we currently live.

Wow, grim indeed. I will be praying for solutions and provision, with gas and food prices I don’t know how people are making it. My stomach is in a knot every time I shop for food as staples cost double.

The inflation measured by CPI is no doubt worse than is being reported. The CPI is rigged and manipulated just like all the Covid data is.

For example, food CPI does not adequately capture "shrinkflation" and "substitution" - substituting cheaper ingredients to camouflage price increases.

Whatever our government says "food inflation" is - you can add X percent to that figure. Overall inflation - recorded the way it was decades ago - would be at least 2X higher than the 8.5 percent "official" figure.