Russia Spiked Oil With Diesel Ban. It Didn't Last.

Prices Rise And Fall Because Of Supply Constraints, Not Demand Increases

Wall Street may not be worried about a government shutdown, but parts of its chattering class has been worried about oil prices, which have been spiking again of late.

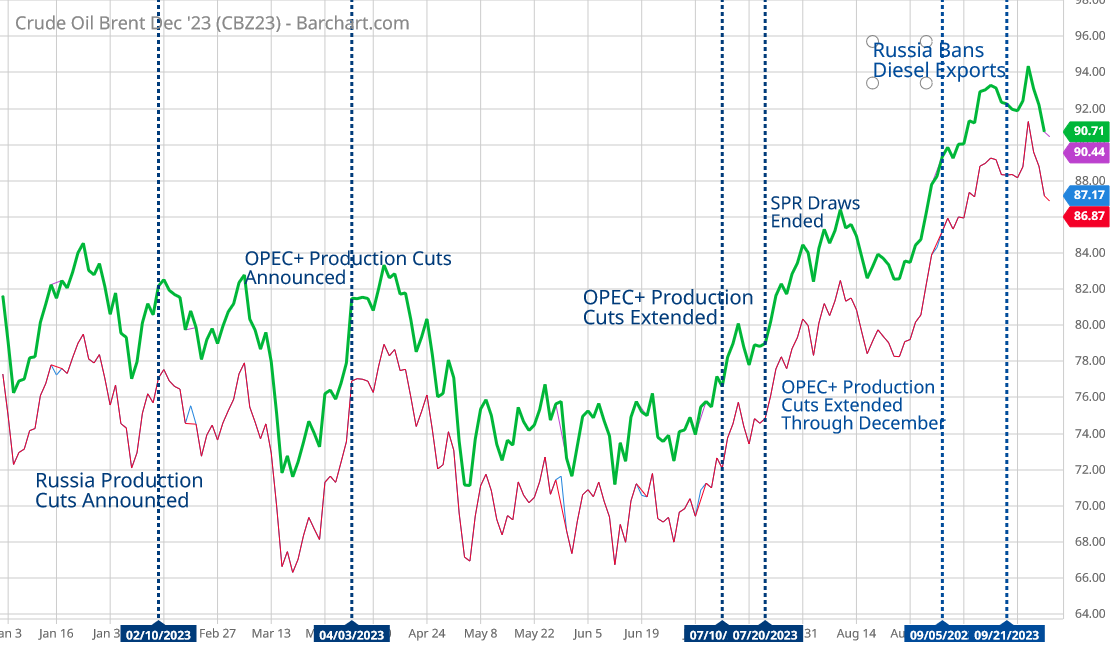

Oil prices (CL=F, BZ=F) have surged to their highest levels in over a year, with analysts suggesting the potential for oil to reach $100 per barrel is coming soon. This price action follows extensive production cuts from both Saudi Arabia and Russia, occurring in lockstep with the U.S. presidential election coming in 2024.

Unlike earlier prognostications, speculations of oil reaching $100/bbl is no longer an outlandish prediction, with Brent crude last week closing above $90/bbl and WTI right behind it at ~$88/bbl.

However, the recent price rises are very much like the previous price rises this year in one important respect: they appear to be driven primarily by artificial and arbitrary constraints to oil supplies, rather than any strengthening of oil demand. Specifically, the latest maneuver has been Russia’s recent decision to ban almost all exports of diesel (and presumably other refined products). This sudden tightening of diesel supply has naturally had a knock-on effect of pushing crude prices up yet again.

Yet the question remains how long can these arbitrary constraints keep oil prices elevated? Without organic demand pressures, supply constraints inherently have only a limited upward pressure on prices. They push prices up, but only so far and only for so long.

Even the analysts projecting $100/bbl oil acknowledge that the upward price pressures have been primarily on the supply side.

Supply cuts from heavyweight crude producers have helped drive oil prices near $100 per barrel — fueling some to consider the potential for future demand destruction.

Brent crude futures rose 63 cents per barrel from the Thursday settlement to $96.01 per barrel on Friday at 11 a.m. London time and sit well above prices observed in the first half of the year.

Without organic demand pressures to sustain price levels, the higher oil prices go the more likely price inflation will help to depress existing demand, which could cause prices to tumble rapidly as they return to previous levels. Too great a supply constraint can result in lower oil prices on a longer timeline.

As a real world case in point, we can see that the most recent spike in oil prices can be attributed to Russia’s late-September decision to keep its diesel and gasoline output for the home market rather than for export.

Moscow has banned diesel and gasoline exports from September 21st. The stated reason has been to stabilise the domestic market, which was seeing some shortages. The ban will remove 1 million barrels per day (mbpd) of motor fuel exports, 80% of which are diesel.

Although crude prices have been rising of late, for a few days prior to that announcement, there were signs of oil prices reaching another plateau as they have in the past. Shortly after Moscow announced the export ban, however, prices moved up again.

Yet as the chart indicates, what went up quickly came down again just as quickly. Which has been the general pattern surrounding all of the artificial supply constraints that have been introduced: Russia’s production cuts, Saudi Arabia’s production cuts, and now the diesel export ban.

Russia and OPEC may have succeeded in pushing prices up, but it is unlikely they will succeed in sustaining these elevated prices. Without organic increases in demand, eventually these prices will fall back down to Earth, and possibly farther.

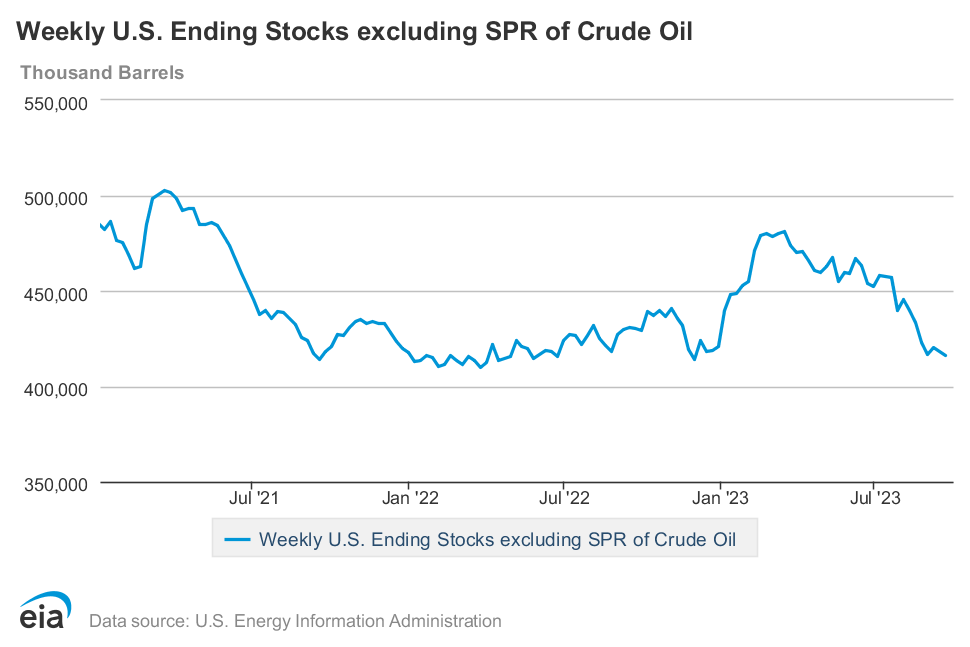

Russia certainly timed its export ban rather well. Although US crude oil stocks had been building earlier in the year, since about mid-March they have been trending down, and are now at their lowest level since December 2022—which in turn is the lowest level going back to at least 2021.

Coupled with the OPEC production cuts—Saudi oil is particularly suited for diesel refining—the loss of diesel supply means other countries have to step up their diesel refining operations, thus putting an upward pressure on crude oil prices.

However, we should not confuse this need for increased refining globally with global oil demand. Ultimately, the world’s diesel consumers are looking to replace supply that they previously could access. They are not looking for additional supply.

One indication we have this is the case is that US stocks of diesel have been rising in recent months.

So far, however, Russia’s diesel ban has had minimal effect on the US markets, primarily because diesel prices had already been on the rise even before the ban, as had gasoline prices.

In the week following Russia’s export ban, diesel and gasoline prices in the US actually dropped.

The drop was even more noticeable when one looks at the various spot prices around the country for diesel and gasoline.

It is not hard to fathom why Russia is pushing an export ban on refined products as well as cutting back on crude oil production—it is contending with the disruptions arising from the war in Ukraine as well as the attendant sanctions.

Russia announced in September a ban on most diesel exports from its western ports in an effort to stabilize fuel prices at home, but later lifted the ban on low-quality diesel. Russia is eagerly pursuing measures that would stave off a repeat of the 2018 fuel crisis. In November 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin saw his approval ratings drop to a low not seen in six years, mainly due to higher prices at the pump, which saw a 7% increase since May. The government’s response was to have oil companies and independent fuel refiners hold wholesale prices at June 2018 levels until the end of the year. Russia then agreed to allow fuel prices to increase in line—but only in line—with inflation.

The move was largely seen as a political, populist, and short-term stop-gap measure.

With the war in Ukraine, Putin is unlikely to tolerate fuel shortages that could influence the approval of the populace.

While Russia is undoubtedly benefiting from the collapse of the EU/G7 price cap, which has allowed Urals crude to rise in price well above the cap of $60/bbl, Russia is also benefiting from having relatively cheaper crude. Because of the lower price, India has emerged as a major consistent buyer of Russian crude.

Cheaper Russian crude compared to Middle Eastern alternatives has prompted Indian refiners to import more crude from Russia in September compared to a seven-month low in August, according to preliminary tanker-tracking data.

India’s crude oil imports from Russia rebounded amid tighter market and more expensive crude from the Middle East, including from Saudi Arabia, which has been raising its contractual selling prices for Asia.

India, the world’s third-largest oil importer, welcomed around 1.55 million barrels per day (bpd) of Russian oil in September, up by 16% compared to August, per LSEG data cited by Reuters.

Indian purchases are undoubtedly part of what has pushed Urals crude above $80/bbl recently.

Still, India’s purchases are mostly replacing previous sales to places such as Europe. India and China are buying more Russian crude, but that also means they are buying less from the Middle East. Aggregate demand is not being increased.

As China doubles down on developing its native electric vehicle industry, oil demand may actually be about to decline from China. Several Chinese energy firms are forecasting peak demand for China either next year or the year after.

Earlier this year, Sinopec and PetroChina saw gasoline demand in China peaking in 2025, driven down by rising sales of electric vehicles. The IEA and Rystad Energy saw the peak in 2024. From there, peak oil demand is only a short step.

But last month, the head of CNOOC went further, suggesting that oil demand in China may have already peaked this year. This is, of course, only a suggestion based on the expected slowdown in demand during the second half of the year, but it does indicate that the industry is preparing for the peak.

If China is reaching peak demand, then the future for Chinese oil purchases is all downhill.

Despite the dramatic rise in oil prices over the summer, OPEC and Russia are still caught in the same dilemma: constraining supply will raise the per barrel price for oil, but it also means less oil gets sold, which in turn limits oil revenue. There is an upper limit to how far OPEC and Russia can use supply constraint gimmicks like production cuts to push oil prices up, after which higher per-barrel prices diminish oil revenues.

But even more challenging is the reality that supply constraints are inherently short-term price pressures. Once OPEC takes a few hundred thousand barrels off the market, prices will invariably recalibrate, and in short order the supply reduction will be fully priced in, and whatever the market price dynamic was before the constraint will likely still be the dynamic after. If oil prices have reached a dynamic equilibrium oscillating around a mean price, once a supply cut get priced in, oil prices will likely oscillate around a new (presumably higher) mean price. If the long term trend in prices is down, a supply cut will raise prices for a time, but the downward price pressures will likely remain even after the supply cut is priced in. If the long term trend in prices is down, pricing in a supply cut may even accelerate future declines in price.

To sustain prices at any level takes a level of demand. Sustainable upward price pressures necessarily come from the demand side. As China’s forecasts of peak oil demand demonstrate, there’s not a lot of demand relative to existing supply. Artificially boosting prices at some point begins to reduce aggregate oil demand.

“Sometimes high oil prices can become a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Indian Energy Minister Hardeep Singh Puri warned in August. “The self-fulfilling prophecy means that at a particular point of time comes a tipping, and then there’s a fall of demand.”

OPEC and Russia have succeeded in pushing the global price of oil up, high enough that $100/bbl for Brent Crude is not out of the realm of possibility. What is out of the realm of probability is that $100/bbl can be sustained for any length of time. For that we will need to see an increase in global aggregate demand, and so far that just has not happened.

Russia pushed the price of oil up close to the magic $100/bbl boundary. What is it going to do to push oil above that boundary? What can it do to push oil above that boundary?