Two months have passed since the WHO issued its first Disease Outbreak News bulletin on cases of acute hepatitis in children, and the outbreak is still as muddled, uncertain, and confusing as it was initially. The answer to the question of cause remains the eternally frustrating “we do not know.”

However, the “experts” are convinced they know what is not the cause: COVID.

“Long COVID Liver”

The source of this outburst of scientific certitude on the basis of little or no evidence was an Israeli retrospective study published in the Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition of five pediatric post-COVID-19 patients who developed subsequent liver injury.

We report five pediatric patients who recovered from COVID-19 and later presented with liver injury. Two types of clinical presentation were distinguishable. Two infants aged 3 and 5 months, previously healthy, presented with acute liver failure that rapidly progressed to liver transplantation. Their liver explant showed massive necrosis with cholangiolar proliferation and lymphocytic infiltrate. Three children, two aged 8 years and one aged 13 years, presented with hepatitis with cholestasis. Two children had a liver biopsy significant for lymphocytic portal and parenchyma inflammation, along with bile duct proliferations. All three were started on steroid treatment; liver enzymes improved, and they were weaned successfully from treatment. For all five patients, extensive etiology workup for infectious and metabolic etiologies were negative.

After excluding all other known causes, the study’s authors concluded that post-acute COVID, also known as “long COVID”, was the probable cause of the liver injury.

We report two distinct patterns of potentially long COVID-19 liver manifestations in children with common clinical, radiological, and histopathological characteristics after a thorough workup excluded other known etiologies.

Researchers and health officials on both sides of the debate have been quick to seize on the study, either to celebrate it as confirmation of their darkest suspicions of COVID-19 or to condemn it as a small, underpowered study standing as a classic example of confirmation bias.

Experts accused of stoking fears throughout the pandemic jumped on the academic paper, accusing health agencies of covering up the long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 on children.

But now infectious diseases experts have dismissed the findings of the study, based on just five children.

While a study of just five patients is almost certainly too small to draw any meaningful conclusions about the hepatitis outbreak overall, even the WHO has considered post-acute COVID-19 conditions as possible causative agents for the hepatitis cases.

The main stumbling block to possible “long COVID” explanations for the hepatitis outbreak remains the reality that proven COVID infection is not documented among a majority of cases (althouh 11 of 12 Israeli hepatitis patients had contracted COVID-19 in the months prior to developing acute liver injury).

Still, a number of public health experts are quite certain that the study’s conclusion of “long COVID liver” is simply not the case at all.

But now infectious diseases experts have dismissed the findings of the study, based on just five children.

Dr Jake Dunning, of Oxford University, tweeted: 'Whatever the cause of unexplained hepatitis in children, this tiny uncontrolled study doesn't provide an answer as to the cause.'

He added: 'One can not simply will Covid to be the cause, just because it supports broader agendas and campaigns.'

And Dr Dunning said hepatitis was only being branded long Covid liver by scientists who 'really should know better'.

Dr. Alasdair Munro of the University of Southampton criticized the study’s design.

A series of five patients, some of whom had hepatitis more than three months after their initial infection, does not establish causality.

'This case series does not look similar to the cluster under investigation in the UK, and does not provide any evidence that the current exceedance of acute, severe hepatitis is due to Covid.'

At the same time, however, Dr. Munro acknowledged that hepatitis can be caused by potentially any viral infection—which means that, despite the high dudgeon some clinicians have over the study and its findings, COVID itself remains very much a possible causative agent.

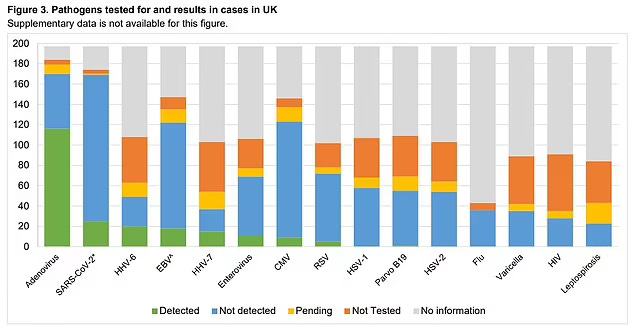

Indeed, one of the major challenges to identifying the causative agent for the hepatitis cases is that no single pathogen has been found to predominate among identified cases.

Adenovirus type 41F has been found in a majority of the cases, but even the adenovirus hypothesis still leaves a large contingent of cases unexplained.

Is There Even An Hepatitis Outbreak?

Strangely enough, perhaps the most notable challenge to the Israeli study comes unintentionally from the CDC, which has not been able to document any significant increase in hepatitis-related emergency room visits as compared to before the pandemic.

Compared with a pre–COVID-19 pandemic baseline, no increase in weekly ED visits with hepatitis-associated discharge codes was observed during October 2021–March 2022 among children aged 0–4 or 5–11 years.

Simply put, the CDC is not certain there is even an hepatitis outbreak to study. While hepatitis of unknown etiology is always disturbing and even scary, it is quite possible that there is no specific syndrome involved in these cases.

However, the CDC is also quick to note that its analysis of relevant electronic health data is itself subject to limitations, and the lack of a clear treatment signal for hepatitis in ER/ED visits does not rule out adenovirus or other viral infection (including COVID-19) as a possible cause for these cases of pediatric hepatitis.

The findings in this report are subject to at least seven limitations. First, although liver transplants are well-documented, cases of hepatitis of unknown etiology are not reportable in the United States. This analysis assessed trends using electronic health data on pediatric hepatitis of unspecified etiology as a proxy, but the exact baseline remains unknown, as does the accuracy and completeness of the diagnostic codes used for identification. Second, data on hospitalizations and liver transplants have up to a 2–3-month lag between outcome and report; March 2022 data might be underreported. Third, the COVID-19 pandemic likely affected observed patterns during the analysis period because of its effects on health care–seeking behavior (9) and infectious disease epidemiology during 2020–2021, and these patterns might still be normalizing. Prepandemic data are limited to 2017–2019, and it is not known whether these data represent a reliable baseline. Fourth, although NSSP and PHD-SR capture a large number of ED visits and hospitalizations, respectively, they do not cover the entire U.S. population, nor do they represent the same catchment areas. Similarly, Labcorp data represent only one large laboratory network and are not deduplicated to the patient level. The extent to which changes in testing volume might be due to changes in laboratory market share or test-ordering practices could not be determined, although the percentage of positive test results should not be substantially affected. Fifth, although the Labcorp assay cannot distinguish between adenovirus types 40 and 41, nearly 90% of adenovirus detections in U.S. children with gastroenteritis are type 41 (10). Sixth, cases of acute hepatitis of unknown etiology are generally rare; thus, small changes in incidence might be difficult to detect and interpret. Finally, these results are intended to provide an overview of trends in pediatric acute hepatitis of unspecified etiology and adenovirus types 40/41 in the United States and cannot be used to infer or disprove a causal link between these two illnesses.

That being said, the CDC is still investigating reports of pediatric hepatitis, and as of June 15 was looking into 290 such cases.

Even the WHO is not entirely sure there is an actual syndrome at issue in the hepatitis cases under investigation.

However, globally the incidence of pediatric hepatitis does appear to be increasing, according to WHO reports.

Most recently, in the months leading up to the Summit, some 700 cases of sudden and unexplained hepatitis in young children have come under investigation in 34 countries. Symptoms of this acute hepatitis come on quickly leading to a high proportion of children developing liver failure with a few requiring liver transplants.

Certainly in the UK, which has the highest number of reported hepatitis cases, the perception among healthcare workers is that the severity of these cases is unusual.

“The severity of this is obviously very concerning, […] you wouldn’t normally see this kind of progression of the disease for sure,” Cary James, chief executive at The World Hepatitis Alliance, told EURACTIV.

Philippa Easterbrook, technical lead of the incident team at World Health Organisation headquarters told a summit on hepatitis that while some cases of hepatitis of unknown origin are reported every year, “in terms of how worried we should be about this outbreak, it’s the first time so many cases of severe acute hepatitis have been seen”

In Europe at least, the reports of adenovirus infection in young children have been higher this year than in the previous five years, indicating that “something” is occuring.

Context is also key to understanding the association between exposures and disease. For example, understanding the current levels of viral infection in the community by different age groups can help investigators understand if infection rates, particularly with adenovirus, are above what would typically be expected. As of April 29, the ECDC reported that the number of positive adenovirus tests in young children (ages 1-4) is currently higher than in the previous 5 years. Between November 2021 and March 2022, 200-300 cases were reported per week, whereas 50-150 were reported per week in the pre-pandemic period.

However, while there appears to be an elevated number of cases at least globally, there is still no clear signal of a specific cause or agent. Indeed, the data suggests that there may be more than one causative agent or factor involved.

The outbreak data collected to date demonstrate that the current cause of acute hepatitis in children may be more complicated than just 1 infectious agent. While the hypotheses of outbreak investigations are subject to change as new data are collected, forming a working hypothesis is critical to the investigation.

This makes the reaction of doctors who reject the Israeli study claiming to show cases of “long COVID liver” rather remarkable. While a study of only 5 patients is an extremely small patient cohort for making any broad determinations regarding disease, the Israeli study at a minimum suggests that post-acute COVID-19 infection—what has been colloquially termed “long COVID”—can cause liver injury and hepatitis. COVID-19 has not been shown to be the exclusive causative agent, but the Israeli study is evidence that it has the potential to play a role in pediatric hepatitis.

Keeping It Simple

As I have observed previously, the guiding principle to be followed is one of simplicity.

While we should always seek to identify the origins and causes of disease, we should not be quick to conclude that a cluster of disease cases represents a distinct outbreak. Hepatitis is caused by a number of pathogens and conditions, and while the cases of pediatric hepatitis being investigated globally cannot be traced to the common causes, that in and of itself does not prove a singular cause among those cases.

The simplest and best understanding of these cases therefore comes back to what I have stated before: people are simply sicker now than before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Exactly why there is a broad decline in general health is itself a question. However, the COVID-19 responses, both the non-pharmaceutical interventions and lockdowns as well as the mRNA inoculations, as the most significant alterations to the overall delivery of healthcare throughout the world in the past two years, deserve strong criticism here. As broad defenses of people’s health, these measures have simply failed.

The lockdowns have failed to protect general health.

The inoculations have failed to protect general health.

Big Pharma has not delivered on improving general health.

The global incidence of pediatric hepatitis is thus a dramatic signal that what we’ve been doing in the pandemic era to protect our health and fight disease is simply not working—and certainly not working as well as it must. Measures which leave people less healthy than before are not good health measures to take, yet the hepatitis cases tell us that is exactly what has happened during the pandemic era; across the board, the COVID-19 measures have left people less healthy.

The lesson to be learned from these pediatric hepatitis cases is to remember what is and is not good medical practice.

Focusing on a single disease is simply not good medical practice.

Restricting treatment options is simply not good medical practice.

Locking down and quarantining entire populations with no symptoms of disease is simply not good medical practice.

Injecting personal opinion and ideology into the delivery of healthcare is simply not good medical practice—and is demonstrably unscientific as well.

Throwing caution to the wind and pushing experimental and dangerous mRNA inoculations is absolutely not good medical practice.

There may not be a single causative agent at play in these hepatitis cases, but there is a single response that is being indicated: we need to stop what we’ve been doing and change direction.

Because $cience?

This is really the culmination of years of catastrophic COVID policies that have come to a head. We've conflated so much of the data because so many factors are likely to have contributed to what we are seeing. Could it be SARS-COV2 infection of the liver, or really any other pathogen because we decided that sterility was more important that antifragility. Are the rises in cancer from the vaccines, or maybe a combination of lack of cancer screening for well over 2 years? The answer to all of these can really boil down to "all of the above" and we really can't discern what some of the causative agents are because everything has been absolutely catastrophic.

The messaging from the CDC is strange, but I suppose it's worth watching out for in the coming days or weeks. I would assume that lingering viral infection or some type of liver tropisms would be weaponized as an argument to get kids vaccinated. Either way we may just have to wait and see.