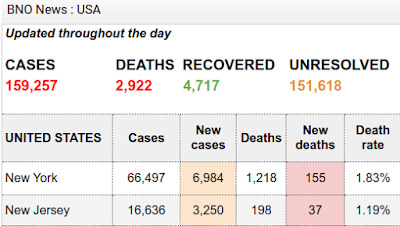

At the end of March there were reported approximately 159,257 confirmed cases of COVID-19 (more properly known as CCPVirus, as it comes to us courtesy of the Chinese Communist Party) infection in the United States. 2,922 people were reported to have died from the disease.

Delving into the data further, we find that 66,497 of those March cases were in New York, while 16,636 cases were in neighboring New Jersey. These two states, together, accounted for 52.2% of all confirmed CCPVirus cases in the US at that time. New York by itself accounted for 41.7% of all confirmed CCPVirus cases at the end of March.

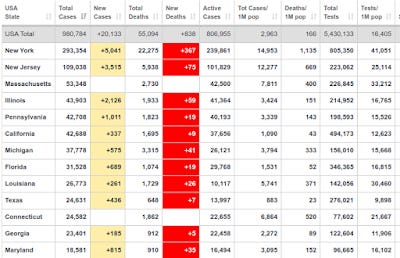

By April 26, the reported number of CCPVirus cases in the United States was 980,784, with 55,094 reported deaths. New York State had 293,354 cases, New Jersey had 109,038 cases, followed by Massachusetts, Illinois, and Pennsylvania in the top five states by case count.

We should pause to note that these are the numbers as reported in the media. As I have noted before, there are significant discrepancies and data integrity questions regarding the actual death toll from CCPVirus. The death tolls are included here merely to present a complete data set.

These are staggering numbers of cases. New York in particular has is a shockingly large number of cases for a single state. New York's case counts are a sobering reminder that the typical US state is, in terms of geographic expanse, population size, and economic size, the equal of many fully sovereign nations, and also a compelling argument for evaluating each US state singly rather than collectively when comparing US CCPVirus statistics to the rest of the world.

It is also not the total number of CCPVirus cases we have in the United States, in New York, or in New Jersey, or in any other state. In spite of all the testing that has been done, significant numbers of cases have managed to go undetected. The precise number of undetected cases is unknown, just as the actual number of influenza cases each year is unknown and must be estimated.

Why has testing not provided better data? Morover, with countries such as South Korea being lauded for their mass testing programs, why has the US not been able to establish the true size of its CCPVirus patient population? Why was South Korea so much more successful than the US?

The short answer is simple: they weren't. The legacy media just tells you they were. The legacy media is wrong (of course), and I will leave it up to the reader to decide if that error is the product of malice, stupidity, or ignorance.

What The Legacy Media Gets Wrong About Testing

When we look at the testing regimes of other countries, South Korea in particular, the first thing we must acknowledge is how few cases of CCPVirus were uncovered. By mid-March, South Korea had administered some 290,000 tests, resulting in approximately 8,000 confirmed cases of CCPVirus. In other words, only 2.7% of the tests administered were of people infected with the CCPVirus.

We must also acknowledge how few tests were actually administered relative to the population. Those 290,000 tests amounted to roughly 0.5% of their population.

By April 26, South Korea had tested 598,285 people, finding 10,728 cases of CCPVirus (a 1.7% positive test result rate).

By comparison, as of April 26, the United States had administered 5,439,388 tests, yielding an 18% positive test result rate. The United States had administered 16,433 tests per million people, while South Korea had administered 11,669 tests per million people. The United States has tested approximately 1.6% of its population, while South Korea has tested 1.1% of its population.

We do not have precise breakdowns between the number of tests administered to symptomatic vs asymptomatic individuals, but even if one assumes an even distribution between symptomatic and asymptomatic people being tested, either one must concede that South Korea never had many CCPVirus cases with which to contend, or their testing regime did not identify all carriers of the virus. Given the uptick in new cases for South Korea at the end of March, subsequent fears of a second wave of infection, and current case counts, it is certain that not all cases of CCPVirus were identified.

Thus, not only does South Korea not have a "mass testing" program (testing only 1.1% of the population hardly qualifies as "mass" anything), but it has not revealed all hidden reservoirs of the disease. Their apparent success in containing the disease must be primarily attributed to the willingness of South Korean citizens to follow protocols of "social distancing" and quarantine. Testing, "mass" or otherwise, has not been a relevant factor in their mitigation efforts.

South Korea's low positive test rates have been largely replicated here in the US. In mid-March, Washington State had a marginally higher positive test rate at 7%, a percentage that has remained fairly stable. Only New York has had a sizable fraction of tests come back positive; the current positive result rate is 35.7%.

The conclusion to be drawn from this is that testing, while an invaluable diagnostic tool, is simply unsuitable for any sort of epidemiological tracking. This is also the somewhat belated conclusion of the "experts", who have at last concluded that, for tracking purposes, confirmed case numbers are "meaningless". It was similar logic that led Los Angeles in March to alter its testing protocol to focus it on diagnosing patients for whom the positive diagnosis would impact the course of treatment.

Why Not Test?

I shall be clear: testing as a diagnostic tool is invaluable, and I am hardly going to challenge doctors on how to treat the sick patient.

However, as important as diagnostic testing is to patient care, neither it nor any other tool is fit to accomplish all things. Tests have their uses, and therefore they have their limitations; we should be mindful of those limitations and not push a tool to a purpose for which it is not fit.

Drawing on my own background of over a quarter century of experience in technology management, I am keenly aware of the limitations of various tools, tests, and metrics for gaining understanding about various phenomenon. In fact, the challenge of identifying the proper metrics has been one of the enduring tasks of technology managers the world over, leading to noted technology author and commentator Bob Lewis to coin "The First Law of Metrics": You get what you measure. There is a corollary to the First Law as well: what you mismeasure, you mismanage.

In the case of CCPVirus testing, attempting to extrapolate from testing to model disease spread was the mismeasurement that led, in multiple instances, to the curious presumed phenomenon of "cryptic transmission." In Washington State, the curious 6-week lag between the first positive test and the second positive test, with both tests showing the viral strain to be related (meaning both patients were on a common chain of transmission), led doctors to quite naturally wonder where the transmission had been occurring, and how had they failed to miss it.

The answer it both simple and brutal: they missed the transmission because, contrary to their presumptions, they were not actually looking for it.

Syndromic Surveillance: Going "Old School"

In assessing the utility of testing, we must remember one thing: illness does not wait on diagnostic tests. CCPVirus infection will work its will on the patient with or without a diagnostic test.

It comes as no surprise, therefore, that even for normal seasonal influenza, only 1.3 million lab tests for influenza have been performed through week 13, despite the CDC estimating at least 39 million cases of influenza and influenza like illness. As a further depiction of the limitation of testing beyond its diagnostic purpose, only 18% of lab tests for influenza yield a positive result; 82% of tests reveal the illness to be something other than influenza.

Yet these numbers illustrate how unnecessary testing is for disease surveillance. Consider: 1.3 million tests is at most 3.3% of all influenza and influenza like illness cases this flu season. For influenza we are not even attempting to use testing as a tracking tool. Yet we have very complete and precise statistics about influenza.

Enter what is known as "syndromic surveillance". Every hospital in every health district in every state in the country reports both numbers if patient visits for influenza like illness and hospitalizations. With or without a test, people who feel sick are going to go to the doctor, and if they are sick enough they are going to be hospitalized. Because so many of the symptoms of CCPVirus are also that of seasonal flu, with or without diagnostic testing, cases of CCPVirus severe enough to warrant a trip to the doctor are going to be capture via syndromic surveillance.

In the case of Washington State's mystery "cryptic transmission", scrutiny of that state's Weekly Influenza Report revealed that, from mid January until mid February, patient visits for influenza like illnesses actually declined. Thus, there was no "cryptic transmission"--the disease quite literally was not spreading in the state during that period.

While it may be "old school", syndromic surveillance is a better method for tracking disease spread for the simple reason that it does not encounter the challenges of estimating how many cases are missed. Where patient visits and hospitalizations rise, it is intuitively obvious that something has made them sick. As epidemiologist Eric Feigl-Ding belatedly noticed about California, using the Weekly Influenza Report to measure levels of infectious disease in California was a viable means of tracking CCPVirus without testing.

Nationally, using the CDC's FluView tracking data, we can easily quantify the severity of the CCPVirus outbreak. The Pneumonia and Influenza mortality data (which includes all Influenza Like Illnesses including CCPVirus) shows an extreme spike to 14% of cases in mid-April, before dropping down to around 11% as of April 23. P&I mortality above approximately 7% is considered an epidemic level of disease, and in recent weeks the United States has been almost double that.

No data beyond this is necessary to establish that CCPVirus is a serious epidemic in this country. Syndromic surveillance is non-controversial because it has been in place for years, giving us a wealth of historical information for comparison and analysis. It is beyond bizarre that "experts" and legacy media alike ignore this data, even as it makes the severity case for them.

With proper measurement comes proper management, and by monitoring the pace of hospitalizations in various parts of the country it is possible for both epidemiologists and crisis management teams to assess which hospital systems are being strained, which ones need resources, and which ones may be plausibly placed on a lower priority.

Contrary to the fears of some doctors, lack of testing does not mean lack of options, nor lack of information. The alternatives are in some regards superior to testing.

How Many Cases?

Without testing, a question invariably arises: how are we to know how many cases of CCPVirus are out there? The answer, of course, is to estimate, in much the same fashion the CDC already does with influenza and influenza like illnesses. Much of the groundwork for building these estimates has already been done. In studying cases of CCPVirus in China, and their proximal origins, researchers have concluded that as many as 86% of new infections came from persons not previously identified as being infected. Viewed another way, 14% of all CCPVirus cases in China were likely documented. Whether that same percentage holds true for the United States is problematic, but if we assume that percentage holds (not unreasonable, given that 20% of all cases of influenza like illness are actually influenza, with the rest being something else), then the confirmed cases amount to 14% of all CCPVirus infections in the country. The 159,257 figure mentioned at the beginning translates into a probable 1.1 million cases of CCPVirus nationwide at the end of March.

To put that number into historical perspective, on June 25, 2009, the CDC estimated there were at least 1 million cases of H1N1 "Swine" flu in the United States. This was 2 months and 10 days after the first H1N1 infection was reported in the US on April 15. With the first case of CCPVirus having been detected on January 19, March 31 is 2 months 12 days after the first detected case. In terms of broad case totals, the size of this outbreak within the United States was on par with the 2009 H1N1 pandemic at the end of March.

The 980,784 reported case total as of April 26 at a 14% detection rate amounts to just over 7 million total cases overall.

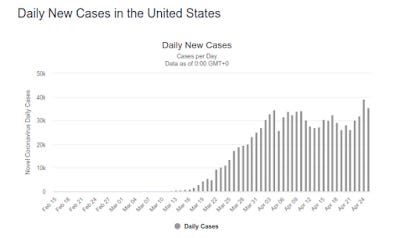

Throughout the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, the CDC estimates the United States had a total of 60.8 million cases. Given that the daily case totals for the United States have largely plateaued since early April, we are quite some distance from the 8.5 million cases we would need to have confirmed at a 14% detection rate to reach 60.8 million CCPVirus cases in the United States.

New York City, the main epicenter of the outbreak here in the United States, had unquestionably peaked by early April.

There is an additional perspective to consider. As we look at the increasing numbers of cases across the country, we should pay special heed to what has been said multiple times and in multiple places: as more testing is done, more cases will be found. Buried in this statement is an important acknowledgement about case numbers: rising case totals indicate the rate of detection far more than they indicate the rate of spread.

As matter of basic statistics, in order for the rate of detection to approximate the rate of spread one would have to randomly sample a population without regard to whether they were symptomatic or not. With testing criteria that seek to weight testing outcomes towards positive results, the rate of detection only broadly hints at the actual rate of spread. It is entirely possible that New York's CCPVirus outbreak peaked as early as late March, even though the new case totals continued to climb into April, simply because increasing testing has been increasing case discovery (and lowering the number of undocumented cases).

Looking Ahead

While there has been a considerable increase in the availability of test kits for CCPVirus, including a 5-minute rapid test from Abbott Labs, reliance on testing for disease tracking will remain problematic for all the reasons already described. Regardless of testing, syndromic surveillance remains the best data analytical tool for epidemiologists and crisis management personnel at both state and federal levels to assess the levels of infectious disease in various regions, and to gauge the burdens placed on hospitals in those regions over time.

A main priority in crisis management is to follow all the available data, to make maximum use of all the information that is available. When it comes to information, too much is never enough, particularly in a crisis. Numbers of confirmed cases is a valuable data point, and no one should ignore those totals. Similarly, no one should ignore hospitalization rates and influenza like illness patient visits in a particular area.

What no one should do, epidemiologists in particular, is focus on diagnostic testing to the exclusion of all other information. For disease tracking, diagnostic testing should be given secondary importance, with primacy placed on the far more comprehensive (and already captured) syndromic surveillance data. In the final analysis, the real concern is not what disease sends people to the hospital, but how many people are being sent to the hospital.

Testing does not answer that question, nor will it.