As the member nations of the European Union continue to debate the proposed sanction mechanism of capping the price for Russian oil, the realities of losing markets is restricting Russian oil prices even without a formal price cap.

In other words, the market is moving ahead of the government regulators. Again.

In its latest effort, the European Commission has (finally) agreed to a $60 per barrel price cap for Russian crude oil.

The European Commission, the European Union’s executive body, has asked the bloc’s 27 member states to approve a price cap on Russian oil of $60 a barrel, according to people familiar with the matter.

Senior officials from the bloc’s member states began discussing the proposal on Thursday afternoon.

The decision by the member states has to be unanimous—every EU nation has an effective veto on the price cap, which makes the probability of the cap actually being imposed rather low.

Even if the EU approves the price cap, both Austrailia and the G7 have to agree to the cap for it to hold.

The price cap is the West’s attempt to squeeze the Kremlin’s oil revenues while keeping global oil supplies steady and avoiding an increase in global energy prices. With it, the Group of Seven and Australia aim to ban the provision of maritime services for Russian oil shipments unless the crude is sold at or under the price.

The G-7 still needs to approve the price for it to go into effect, and the group might not immediately agree with the EU decision. Under the system, companies shipping Russian oil will still be able to access EU insurance and brokerage services if they sell the oil at or under the price-cap level.

Thus while the EU leadership itself knows the price cap it wants to set, it still faces a monumental task of herding the geopolitical cats to make the price cap a reality.

The current proposal is also timed to be implemented concurrent with a December 5 start date for an EU embargo on Russian crude delivered by ocean vessel, originally enacted back in June. The embargo is part of a larger set of restrictions on the sale and shipment of Russian hydrocarbons.

1. It shall be prohibited to purchase, import or transfer, directly or indirectly, crude oil or petroleum products, as listed in Annex XXV, if they originate in Russia or are exported from Russia.

2. It shall be prohibited to provide, directly or indirectly, technical assistance, brokering services, financing or financial assistance or any other services related to the prohibition in paragraph 1.

In addition to banning the purchase of Russian crude by EU member states, it will also be prohibitied to provide services such as the various forms of insurance required by oceangoing vessels, which gives the EU embargo a bit of global consequence. Countries such as China can still purchase Russian crude (the EU has no capacity to impose a legal embargo on non-member states), but will have to do so without ships reliant on EU financial services companies to provide all the necessary certificates of insurance required for a modern oil tanker.

A critical part of the sanctions package (Article 3n) concerns shipping insurance. After a six-month phase in period, EU companies cannot provide “technical assistance, brokering services or financing or financial assistance, related to the transport, including through ship-to-ship transfers, to third countries of crude oil or petroleum products” from Russia. The United Kingdom is expected to follow suit. Cutting off shipping insurance and reinsurance from the European Union and United Kingdom—the heart of the maritime insurance industry—will hinder Russia’s ability to redirect crude oil and petroleum products to other regions. Shipowners will be reluctant to lift Russian cargoes that cannot be insured or reinsured, and such vessels could even be barred from some ports.

While it is theoretically possible that China especially might agree to indemnify tankers filled with China-bound Russian oil, given that the size of the maritime insurance industry is $26.83 billion as of 2020, and is projected to grow to $33.9 billion by 2028 it is debatable if China has the economic heft to re-invent that particular wheel to encompass cargoes bound for nations besides China.

The irony of the price cap is that Russia’s benchmark Urals crude oil currently trading at $66.54 per barrel.

That puts Russian crude at a deep discount to Brent crude, which is currently trading at $87.929 per barrel.

The discounted price for Russian crude has been an immediate and proximate consequence of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and the attendant EU sanctions. Prior to the war in Ukraine, the Urals price tracked closely with the Brent crude price.

Why the discounted price? With EU actively working to prohibit any future purchase of Russian crude by EU member states, and with some other countries also banning Russian crude, Russia has lost export customers for its hydrocarbons. Thus, even with a general downward trend in the price of crude oil, the primary remaining buyers for Russian crude enjoy considerable leverage in setting the price—and use it.

But switching flows to Asia, where India has emerged as Russia’s second-biggest customer, has concentrated Moscow’s dependence on an ever-shrinking pool of buyers. China and India now purchase two-thirds of all the crude exported by sea from Russia; at least half of the crude exported by pipeline from Russia also goes to China.

That gives huge negotiating power to buyers in both countries, and it’s a power they have exercised. Russian crude is trading at a hefty discount to international benchmarks, and that is hitting the Kremlin’s war chest.

Countries are buying Russian crude because they are bargain hunting.

This is confirmed by China’s moves regarding another hydrocarbon, natural gas. Having signed long-term delivery deals first with QatarEnergy and then with BP, China is not showing Russia any preference as an energy supplier.

Additionally, economics could impose not just an effective price cap on Russian oil but a production cap as well in the future. With European and American energy firms having almost entirely pulled out of Russia, a period of underinvestment in Russian oil and natural gas fields is potentially looming.

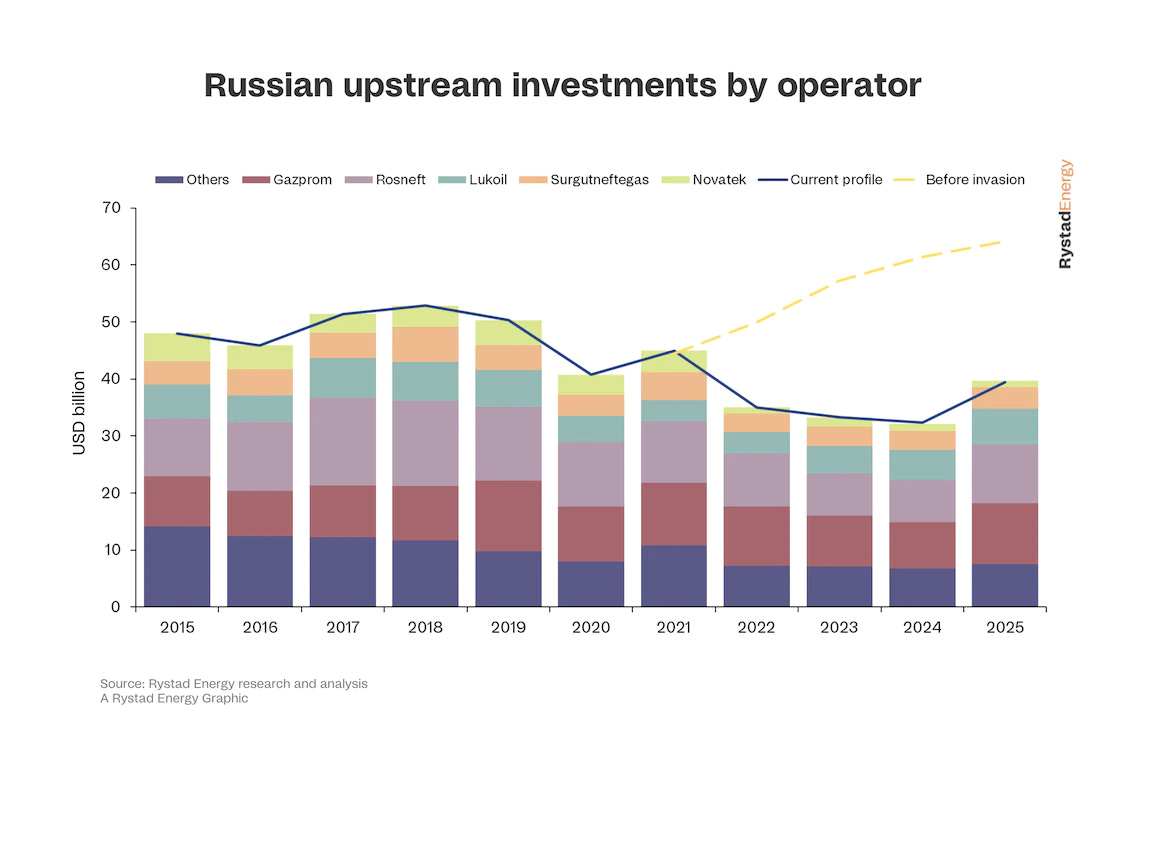

Energy research company Rystad Energy is forecasting total upstream investments in Russian oil and natural gas will drop by $15 billion this year, and will decline even further in 2023 and 2024, before recovering in 2025.

Investments in Russia’s upstream sector totaled $45 billion last year, rebounding from Covid-19-induced lows of $40 billion in 2020. But as Russia becomes increasingly shut off from the global energy market, investments have sunk well below levels seen in the pandemic-affected years of 2020 and 2021 and will remain subdued until at least 2025. The stagnation in investments will lead to a drop in project final investment decisions and force operators to make hard decisions on spending. While domestic giants Gazprom and Rosneft will be able to keep spending around 2021 levels, other players will see a significant drop in investments.

The most notable sign of underinvestment is that no projects are on deck.

No significant new projects are expected to be sanctioned in Russia next year, but activity will resume in 2024 with the Gazprom-operated Chayandinskoye (Phase 2) gas-condensate field – a resource base for the Power of Siberia-1 gas pipeline to China – and the Payyakhskoye oilfield, part of Rosneft’s huge Vostok Oil project in the north of the country.

Without ongoing investments in oil and natural gas fields, their production quickly tapers off. With the development and discovery of new oil and gas fields, Russia’s oil production will not merely be reduced in the short term, but will remain reduced in the long term as well.

Thus, even if the EU price cap comes into effect, it will have only minimal effect. It will not suppress prices for Russian crude much (if at all). It will not inhibit the production of Russian crude. Long before the price cap can have a chance to function at all, other forces are in play which are constraining Russian oil production and export far more than the price cap is likely to accomplish. The price cap would help sustain those pressures to suppress Russian oil production, but that appears to be the only practicable benefit the price cap is likely to have.

Which makes the EU price cap overall an extended geopolitical exercise in futility.