The Fed Is Not Fighting Inflation, But Causing It

Jay Powell Is Repeating The Policy Mistakes Of The Past

I am a geek and a nerd. As an accountant turned voice and data network engineer, it would be difficult for me to be anything but.

As a consequence, I have an eternal fascination for numbers.

In writing this newsletter, my constant challenge is giving numbers relevance to others, to explain the importance of various points of data and what they say about things that directly impact people’s lives—and to do so in a way that does not cause eyes to glaze over!

When discussing COVID-19 issues, the relevance is fairly easily intuited: people want to be healthy and not sick, and knowing what the data actually says gives them the best chance of accomplishing that.

When the time comes to address the economic consequences of government and societal responses to the pandemic, tying diverse facts together in a meaningful way becomes rather more challenging.

All of which is a long-winded way of saying “bear with me (please!)” as I turn my attention to the Federal Reserve’s new-found urgency on fighting inflation—the inflation it has demonstrably caused by its loose money policies both before and during the pandemic (causes which I have discussed at length before, for those desiring a fuller background).

Alas for the Fed, that anti-inflation urgency is an illusion. Far from confronting inflation, the Federal Reserve is making the situation worse.

The Fed Finally “Gets It”—Inflation Is Real, Not “Transitory”

We should perhaps be somewhat encouraged that Fed Chairman Jay Powell has finally dispensed with the “transitory” narrative on inflation and accepted its reality, and has committed to doing “something” about it.

The Federal Reserve on Wednesday said it is likely to hike interest rates in March and reaffirmed plans to end its bond purchases that month in what U.S. central bank chief Jerome Powell pledged will be a sustained battle to tame inflation.

"The committee is of a mind to raise the federal funds rate at the March meeting assuming that the conditions are appropriate for doing so," Powell said in a news conference, pinning down a policy statement from the central bank's Federal Open Market Committee that only said rates would rise "soon."

What gets lost in the newspeak, however, is the unfortunate reality that the Federal Reserve is itself the cause of the inflation it now has pledged to fight.

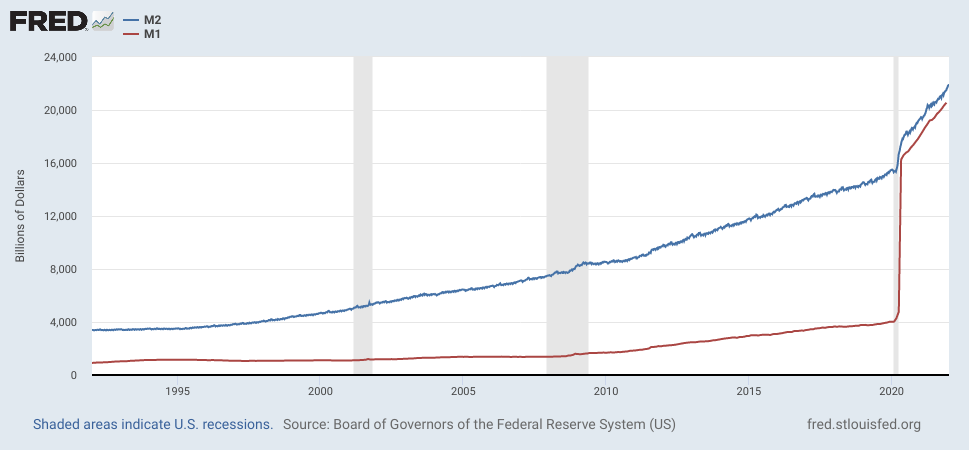

What the Federal Reserve refuses to admit is that asset price inflation within financial markets dates back to the 2008 financial crisis and attendant recession. When one looks at the trends among the major stock indices compared to movements in the M1 Money Supply, the correlation between the Fed’s “Quantitative Easing” programs and the rise in financial asset prices is immediately obvious.

Where did the money go? Quite simply, the money went to the big banks and hedge funds--the engines of investment on Wall Street. We can see this in the convergence of money supply growth and stock market prices (represented by the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 index) that happened at the same time the CPI diverged from money supply growth.

As the chart clearly shows, before 2008 the stock markets moved independent of the money supply, but not after. In fact, if we zero in on events after 2008, we see that the M1 money supply imperfectly raised stock market asset prices, as the widening gulf between the M1 supply and the stock market indices indicates.

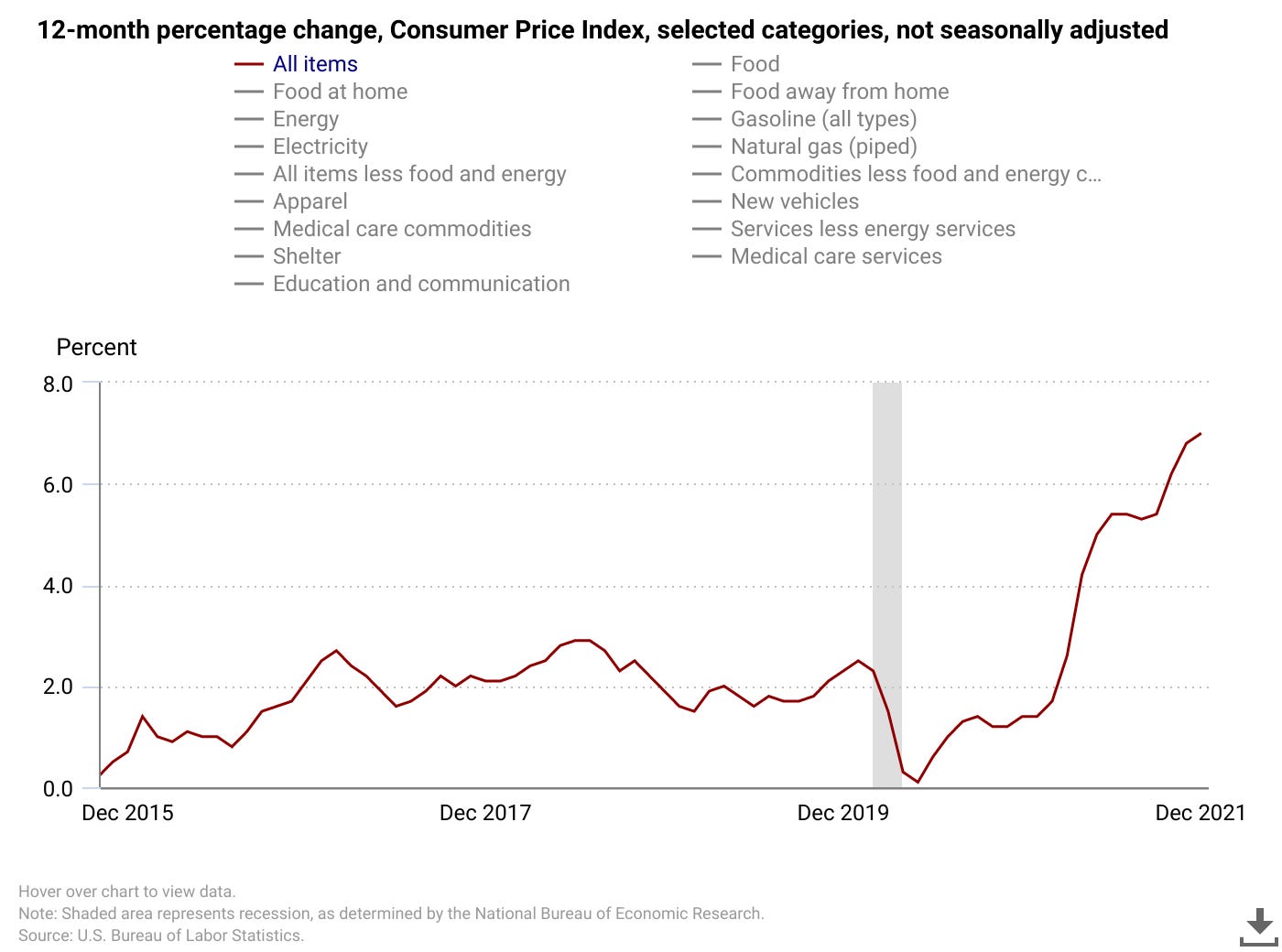

What has changed over the past 18 months is that this inflation has moved beyond the markets to the general economy. While inflation had been contained to just Wall Street, beginning in early 2020 inflation also began to affect Main Street, as illustrated by the rise in the Consumer Price Index.

Inflation Is The Fed’s Own Doing

Because the Federal Reserve has kept interest rates at or close to zero for years, the available supply of money has expanded by several orders of magnitude since 2008, and particularly since the pandemic lockdowns began in 2020, as the Federal Reserve’s own data on the M1 and M2 metrics for the supply of money in the US demonstrate.

This growth in the money supply has been deliberate, rationalized as a means to cushion the economic shocks that inevitably followed the government decisions to shut down whole portions of the US economy in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In response to covid-19 and in particular the lockdowns and other restrictions, central bank officials expected severe damage to the economy. The economy was expected to fall strongly below the path of stability. In this case, strong monetary pumping was considered as a welcome move. The strong monetary pumping is believed to have brought the economy onto the stable path.

Exactly why this was thought to be a good idea is a mystery, because increasing the money supply is by definition inflation, and increasing the money supply in response to an actual decrease in the quantity of goods and services available can only be even more so.

But monetary pumping cannot generate economic stability. The pumping sets in motion an exchange of nothing for something, or the diversion of wealth from wealth generators to the early recipients of the newly pumped money. This undermines the process of wealth generation and weakens the prospects for economic growth.

As a rule, because of the monetary pumping, individuals are going to have more money in their pockets, which they are likely to dispose of by buying goods and services. This means a greater amount of money is going to be spent on various goods and services. This means that the prices of goods and services are going to increase, all other things being equal.

In other words, the Federal Reserve, having caused inflation by artificially expanding the money supply, now proposes to conquer that same inflation by reducing the money supply, as Chairman Powell assures us the Fed knows how to contain inflation.

Chair Jerome Powell said at a news conference that inflation has gotten “slightly worse” since the Fed last met in December. He said raising the Fed’s benchmark rate, which has been pegged at zero since March 2020, will help prevent high prices from becoming entrenched.

Unfortunately for Jay Powell—and for the economy—the Fed’s proposed strategy for fighting inflation—incrementally raising interest rates—is almost certainly an inadequate response to inflation, if the Fed’s own history is any guide. Jay Powell might seem to be proposing the right medicine, but the dosage levels he's prescribing are not going to cure anything.

If all the interest rate hikes priced in by financial markets come to be, the Federal Reserve will raise base interest rates by maybe a percentage point, at most two.

The Fed held its key interest rate near zero Wednesday but said it will “soon be appropriate” to raise it, hinting that a rate hike in March is all but certain. The increase would be the first in more than three years and kick off what’s likely to be a flurry of three or more quarter-point increases this year aimed at reining in sharply rising consumer prices.

For inflation which is at 7% and rising, the Fed's own history suggests that is simply not enough of an increase.

The “Cure” For Inflation: Raise Interest Rates—A Lot

As those old enough to remember the last time the Federal Reserve had to tame significant inflation will recall, the conventional "cure" for rising inflation is to raise interest rates—a lot.

In general, as interest rates are reduced, more people are able to borrow more money. The result is that consumers have more money to spend. This causes the economy to grow and inflation to increase.

The opposite holds true for rising interest rates. As interest rates are increased, consumers tend to save because returns from savings are higher. With less disposable income being spent, the economy slows and inflation decreases.

This correlation deserves particular notice. Borrowing gives people more money becuse more money is created, not because overall economic output has increased. This is an inevitable byproduct of borrowing and debt.

As a heavily simplified demonstration of the money supply grows, suppose that when someone deposits $100 into the bank, they maintain a claim on that $100. The bank, however, can lend out those dollars based on the reserve ratio set by the central bank. If the reserve ratio is 10%, the bank can lend out the other 90% (which is $90 in this case). A 10% fraction of the money stays in the bank vaults.

As long as the subsequent $90 loan is outstanding, there are two claims totaling $190 in the economy. In other words, the supply of money has increased from $100 to $190.

When people borrow money to increase spending, they are not increasing their own economic output in the process: they are not working more hours, nor producing more goods, nor delivering more services. In other words, by borrowing to spend, people are using more dollars to purchase the same overall quantities of goods and services—which is the functional definition of inflation.

Surprisingly, this is well accepted and understood within economic and financial circles.

In economics, the quantity theory of money states that the supply and demand for money determine the rate of inflation. If the money supply grows, prices tend to rise. This is because each individual unit of currency becomes less valuable.

Just as lower interest rates leads to increased borrowing which leads to an increased money supply, higher interest rates leads to decreased borrowing and a decreased money supply. As price inflation is the result of an expansion of the money supply, curing inflation involves reducing the money supply.

It was this understanding of the linkage between the supply of money and the rate of inflation that was led to former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker’s 1979 proposal to tackle “the Great Inflation” with dramatic interest rate hikes.

However, some members of the Federal Open Market Committee remained concerned about the level of inflation, and Volcker made a dramatic move to attack the problem. During a rare press conference on the evening of October 6, 1979, the Saturday before Columbus Day, Volcker announced the results of an unscheduled FOMC meeting held earlier that day.

In front of reporters who had rushed to the Eccles Building to cover the unexpected announcement, Volcker explained the FOMC would shift its focus to managing the volume of bank reserves in the system instead of trying to manage the day-to-day level of the federal funds rate (Lindsey et al. 2005). It was an approach that would lead to more fluctuation in rates and, Volcker hoped, rein in inflation.

The “Great Inflation”: Fed Policy Failure

Volcker’s solution to inflation is relevant because, just as is the case today, the runaway inflation of the 1970s was the accumulated result of repeated Fed policy errors which allowed for a rapid expansion of the money supply to fund government largesse aimed at stimulating the economy.

Motivated by a mandate to create full employment with little or no anchor for the management of reserves, the Federal Reserve accommodated large and rising fiscal imbalances and leaned against the headwinds produced by energy costs. These policies accelerated the expansion of the money supply and raised overall prices without reducing unemployment.

While the proximal motivations are slightly different, the reality of Federal Reserve policy since 2008 has been a similar accommodation of large fiscal imbalances (federal budget deficits) in order to stimulate the economy. The result of these policies has been an increase in the money supply and a general rise in prices, just as happened in the 1960s and 1970s.

In short, we've been here before. We are facing today the same problems of inflation caused by the same expansion of the money supply in pursuit of the same hope for economic stimulus as was the case 40 years ago. The Federal Reserve is faced with the same challenge of reining in money supply growth.

Even the economic and political risks are the same.

With interest rates high in the Volcker-led fight on inflation, the attacks came from both political parties. “We are destroying the small businessman. We are destroying Middle America. We are destroying the American dream,” conservative Congressman George Hansen said during a 1981 hearing (Todd 2012). During the same hearing, Democrat Frank Annunzio shouted and pounded his desk, accusing the Fed of favoring big business, and Texas Congressman Henry Gonzalez threatened to introduce a bill to impeach Volcker and most of the Fed’s other governors.

A couple of weeks later, Treasury Secretary Donald Regan directly criticized the Fed’s position during an interview with a New York Times reporter.

“What I am suggesting is that if (money supply growth) stays here, you’re going to have a severe recession,” said Regan, who then went on to suggest how the money supply needed to be adjusted going forward (Todd 2012).

Donald Regan's assessment then is almost identical to the assessment now from financial news outlet Bloomberg: too much monetary tightening risks an unexpectedly severe economic contraction.

Indeed, as Bloomberg put it, “A predictable normalization path should help engineer an easy landing, but if financial conditions tighten too sharply between now and then, particularly in the credit markets, the Fed risks inducing a sharper economic slowdown than they may deem desirable.”

Despite the challenges, Paul Volker pushed the benchmark federal funds rate to 20% by the fall of 1980 to overcome inflation that peaked at around 14.6%.

Inflation today is at 7% and rising, making it every bit as bad as inflation back then. Jay Powell is proposing pushing the federal funds rate to maybe 2%, assuming he sticks to his guns and does not get bullied by the markets into reversing his tightening efforts, as happened in 2019.

Given the broad parallels between 1979 and 2022, between the causes of inflation then and now, as well as the impacts, it is not unreasonable to conclude that interest rates today need to rise to a similar level as in 1979-1980. That suggests interest rates need to rise to at least 7-10% and possibly more if inflation is to be beaten back. That rise needs to happen now, not twelve months from now.

The Federal Reserve is not even discussing anything remotely like this. Volcker's successful anti-inflation strategy is being ignored.

There Will Be Blood

One lesson from the Great Inflation seems unavoidable: taming inflation involves economic pain and economic contraction. Paul Volcker quite deliberately catalyzed the 1981-1982 recession in his quest to tame inflation; if Powell means to replicate Volcker’s success, he must be willing to replicate it all, the good as well as the bad. If consumers want inflation tamed, we must understand there will be consequences.

We should understand that, prior to the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession, the 1981-1982 recession was worst economic downturn since the Great Depression, with unemployment rising as high as 11%. Throughout the contraction Volcker faced considerable pressure to ease his strong anti-inflation policies. He resisted, even in the face of calls by House Democrats for his resignation, and by 1982 succeeded in reducing inflation below 5%.

Of particular relevance to today is one of the claimed “lessons learned” from Volcker’s campaign against inflation: the gradual, incrementalist approach to managing monetary policy was discredited, becoming viewed as the sort of policy error that made inflation and the economic disequilibrium of the 1970s even worse.

If we apply that logic to the current Fed plan to increase interest rates in 0.25% increments spread out over the coming year, the conclusion must be that such a plan is a mistake—it is exactly the sort of gradual incrementallist approach that Volcker rejected. Micromanaging the money supply and interest rates in this fashion merely kicks the proverbial can down the economic road, making inflation and the inevitable reckoning that much worse.

This much is certain: inflation is real, and it's a real problem. Inflation is already stealing the wage gains workers have achieved, and then some; simple math shows that the 2.6% average increase in weekly wages over the last quarter of 2021 is obliterated when official inflation runs at 6.7% over the same period. Working men and women are losing money to inflation, and will continue to lose money the longer inflation remains unchecked. Unlike the unemployment that results from a recession, losses to inflation are permanent.

Far from confronting inflation, the Federal Reserve is repeating the policy mistakes that caused inflation in the 1970s, and made recession not only inevitable, but worse than it otherwise might have been. The Fed is not providing a solution, but is itself the problem.

The Fed is repeating its own history. History tells us how that will end…badly.

The Fed can't raise rates to "at least 7-10% and possibly more" like it did 40 years ago. The US Government has $30T in debt now, and most of it is short-term, meaning it needs to rolled over, on average every few months to a year or so. Look at what would happen to the FedGov's budget if interest rates rose to that level. The FedGov and Federal Reserve painted themselves into a corner back in 2008-2009, and I see no way out. What they've done in the last two years just made things worse.