It has now been a full two weeks since the EU imposed its price cap on seaborne Russian oil exports.

At the present time, the price cap appears to be holding. Is it having the desired effects of limiting Russian oil revenues? Trade data suggests that it is.

Despite Putin’s vows not to abide by the price cap, market forces have called him on that promise, and there are no signs as of yet that Russia is refusing to sell under the price cap.

As of this writing, Russia’s flagship Urals crude oil blend is trading at a spot price of $54.47 per barrel.

Urals crude declined sharply after the price cap took effect, and while there was a brief price rally a few days later, the rally did not hold, sending the price lower again.

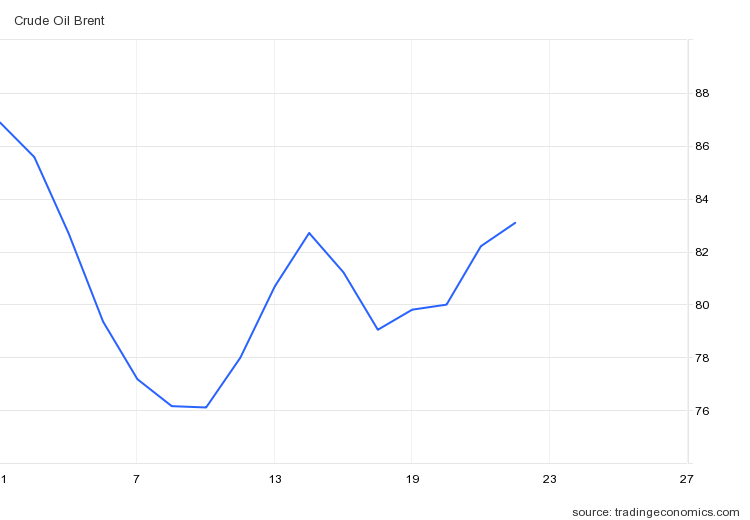

At the same time, Brent crude—the benchmark oil price for Europe—has also declined, and as of this writing trades at a spot price of $83.63 per barrel.

It’s worth noting that, while Brent and Urals crude have shown similar price fluctuations, in recent days Brent crude has risen, although still significantly below the spot price from just before the price cap took effect.

One consequence of Brent’s rise and Urals fall is that the discount for Urals crude has increased to over $29 per barrel. That discount by itself limits Russian oil revenues.

The discounts have increased for Russia’s ESPO and Sokol blends as well.

ESPO in particular has declined by over $12 per barrel to $66.23, widening the discount on that blend to $17.4, a considerably greater discount than the approximately $4 per barrel that was occurring when the price cap was imposed.

In addition to falling prices for Russian oil, oil exports have also declined for Russia.

After a brief uptick in oil leaving Russian ports, last week shipping volumes declined to previous levels.

Lower volumes at lower prices makes Russia’s oil revenues are overall lower. Even at higher volumes and prices, such as existed before the price cap, the market-enforced discount to Urals crude was already cutting in to Russia’s oil revenues, according to the International Energy Agency's December Oil Market Report.

Russian oil exports increased by 270 kb/d to 8.1 mb/d, the highest since April as diesel exports rose by 300 kb/d to 1.1 mb/d. Crude oil loadings were largely unchanged m-o-m, even as shipments to the EU fell by 430 kb/d to 1.1 mb/d. Loadings to India reached a new high of 1.3 mb/d. Export revenues, however, dropped $0.7 bn to $15.8 bn on lower prices and wider discounts for Russian-origin products.

Russia sold more oil in November but saw less money from the sales.

With prices falling further since November, and the discount widening, Russia’s export revenues for December are certain to be even lower.

As a matter of pure market dynamics, the price cap is achieving its goal of reduced Russian oil revenue without limiting Russian oil supply.

There are even indications shippers are reluctant to accept ESPO blend oil at the far eastern port of Kozmino, near Vladivostok. Since the price cap took effect, loadings at Kozmino have dropped by half.

Since Dec 5, buyers of cargoes from Russia have been allowed to access industry standard insurance and an array of trade-critical services only if they pay US$60 (S$81) a barrel or less. Shipments from the Asian port of Kozmino are about US$10 above that, meaning they need to make alternative arrangements.

But there are signs they might be struggling to do that. In the 10 days since the measures began, 4.4 million barrels have been loaded onto tankers at Kozmino, tanker tracking compiled by Bloomberg shows. That is exactly half the month-ago level and there is nothing due to load on Thursday.

Additionally, there are reports that ESPO sellers are having difficulty finding tankers willing to take the oil at the market’s above-cap price.

Shipbrokers and traders also said there are signs that ESPO sellers are struggling to secure tankers for cargoes purchased at more than US$60 a barrel.

At least two large and well-known shipowners, China Cosco Shipping Corp and Greece-based Avin International, have stepped back from moving ESPO crude since Dec 5, according to shipbrokers.

This may account for the widening discount on ESPO oil.

Adding to the revenue reduction from the price cap is the steep drop in production on Sakhalin Island, the source of Russia’s Sokol blend.

Oil production at Russian Pacific island of Sakhalin is expected to fall by 44% this year to around 9 million tonnes (180,000 bpd), Interfax news agency cited a local official on Monday.

Oil output at Sakhalin, which produces Sokol grade for exports to Asia, collapsed after the U.S. energy major Exxon Mobil left Russia following the start of Moscow’s special military operation in Ukraine on Feb. 24.

While the drop in production on Sakhalin pre-dates the price cap, it still increases Russia’s recent oil revenue losses.

An additional indicator of the price cap’s impact on Russian oil exports is the decision by one of Russia’s top insurers, Ingosstrakh Insurance Co., not to expand its insurance coverage of Russian oil tankers.

“Ingosstrakh does not plan to expand its P&I portfolio by offering P&I policies to new clients, who may lose coverage from international P&I clubs after new restrictions came into force on December 5,” the firm said in a statement.

So long as shippers need European insurers to cover oil tankers, the price cap is going to be effective, as lack of insurance can bar a ship from many of the world’s ports, as well as waterways such as the Suez Canal and the Turkish straits connecting the Black and Mediterranean Seas.

This lack of insurance options may mean that Putin’s vow not to sell under the constraints of the price cap may prove to be a bluff. Certainly at the present time, indications are that it is a bluff, as even India, which has generally refused to play along with sanctions on Russian oil, is apparently receiving its oil on tankers properly insured by western insurers—carrying oil that is of course being sold under the price cap.

Russian crude oil is being shipped to India on tankers insured by western companies, in the first sign Moscow has reneged on its vow to block sales under the G7-imposed price cap.

At least seven Russian crude oil cargoes have been loaded on to western-insured tankers since the price cap started on December 5, according to Financial Times analysis of shipping and insurance records, despite President Vladimir Putin’s claim that Moscow would not deal with any country observing the cap.

As a result of EU sanctions on Russian oil, India, along with China and Turkey, has emerged as one of the major purchasers of Russian oil, with nearly 90% of Russian crude being shipped to Asia instead of Europe.

European nations took in approximately half of Russia's crude supplies before the war in Ukraine began, but that's all but halted, with the exception of a small volume of imports to Bulgaria. Russia is diverting most of that crude to Asia, with 89% of all Russian shipments — about 3 million barrels a day — heading there in the week ending December 9, according to Bloomberg.

Russia shipping oil to India on tankers insured under price cap guidelines means that Russia was in fact bluffing when it threatened not to do business under the price cap. Certainly India, nor China, nor Turkey, are going to pay more than market price for Urals crude.

Russia had even gone so far as to offer to aid India in obtaining large tankers of its own, which would presumably aid it in circumventing the price cap.

At a meeting Friday, Russia's deputy prime minister, Alexander Novak, welcomed India's decision not to go along with the price cap and put forward its offer of help to Pavan Kapoor, the Asian country's ambassador to Moscow.

"In order not to depend on the ban on insurance services and tanker chartering in the European Union and Britain, the Deputy Prime Minister offered India cooperation on leasing and building large-capacity ships," the Russian Foreign Ministry said in a statement.

Developing its own tanker fleet is a measure Russia has been implementing for quite some time in anticipation of the cap.

Yet even such measures, or aiding other countries in expanding their own tanker fleets, will do little to aid Russia’s efforts to circumvent the price cap when the price of oil is remaining under the cap. With the spot price for Urals crude currently below the price cap, all sales of Urals crude complies with the price cap. While ESPO and Sokol blends are currently still above the cap, their volumes are far less than for Urals crude, and so do little to alter the oil market reality for Putin: he can sell oil under the price cap or he can not sell oil at all.

That the price cap is apparently increasing the discount on ESPO crude serves to empahsize the cap’s impact on Russian oil markets.

The real test of the cap will of course be when market forces push Brent crude up, taking Urals crude along for the ride. So far that particular day of reckoning has not happened, and while that time may come—perhaps as early as next year—for now the price cap is holding.

With Russia’s oil revenue reduced by $700 billion in anticipation of the cap, and oil prices holding where they are, promising further reductions, Europe’s price cap on Russian oil is so far achieving its stated objective.