There's A Recession...We Need More Stimulus!

Never Mind That Recession Is Exactly What The Fed Wants

With the formal recognition of the recession we’ve been in for a while is now just a matter of time, the corporate media is almost reflexively hyping the government’s “tried and true” solution to recession: “stimulus”.

These days, a growing number of experts are sounding warnings about a potential recession. Now the reality is that we can't say with certainty if economic conditions will worsen substantially in the near term, and when a recession might hit. But there's reason to think we could be headed for a downturn in the not-so-distant future.

That's the bad news. The good news, however, is that if a recession does hit, lawmakers may fall back on a solution they've long employed -- stimulus checks.

Yep, whenever the economy contracts, the “experts” always think the solution is the same: print and pump more money.

After all, stimulus checks always goose demand….right?

Do Stimulus Checks Really “Stimulate”?

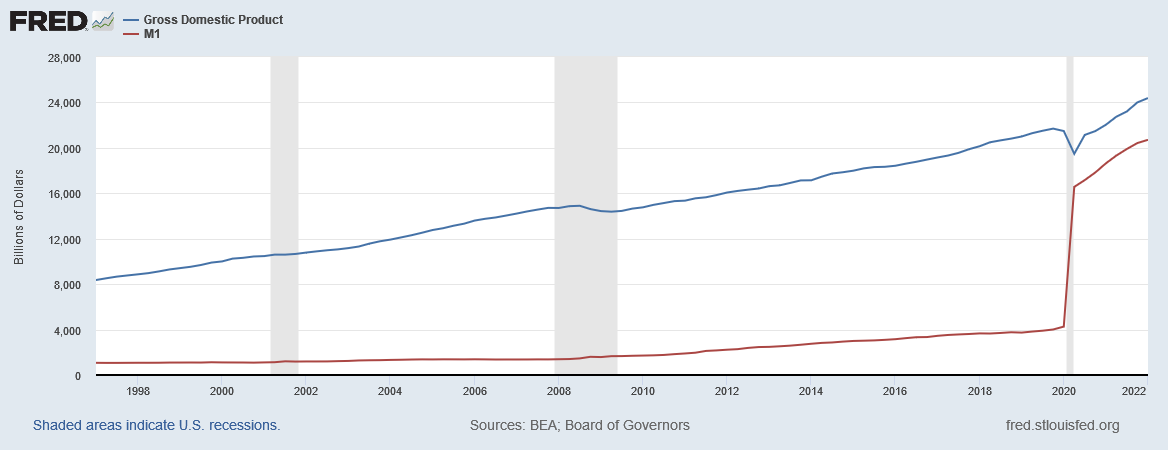

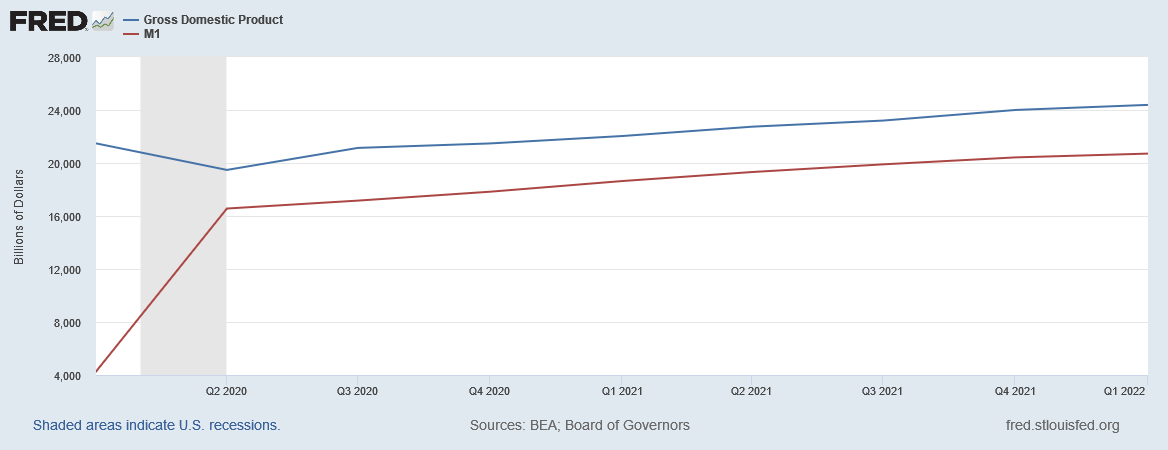

The actual efficacy of direct transfer payments to consumers is problematic at best. In 2020, the Federal Reserve dumped a massive amount of magically created money into the economy, but without a spike in nominal GDP to match the M1 money supply growth

One could argue that the economy responded somewhat to the post-recession “stimulus” (as represented by the continued growth in the M1 money supply), as the growth rates for both nominal GDP and the M1 are more or less the same.

Given the parallel tracks for nominal GDP and the M1 money supply after the 2020 recession, one could argue that had the M1 been reduced, in order to “drain” the massive infusion of money back out of the economy, nominal GDP would have crashed, sparking a new pandemic era recession.

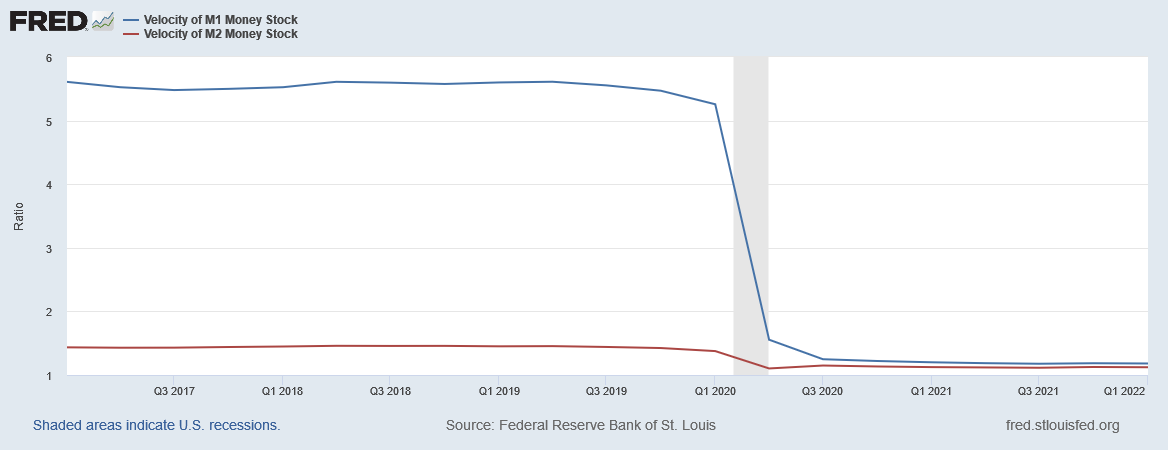

Why did the economy as measured by growth in nominal GDP not respond to the spike in the M1 money supply (the pandemic “stimulus” writ large)? Remember, as I outlined in “Modern Monetary Insanity, Part 2”, during the 2020 recession M1 money velocity crashed to near zero, thus largely negating any capacity of “stimulus” direct infusions of money to boost GDP.

Money supply velocity crashed and stayed crashed, thereby negating any capacity of money supply infusions to stimulate anything (even, perversely enough, inflation).

Consequently, there is little reason to believe that any monetary stimulus will work at this point. Until money supply velocity is restored, stimulus checks will be largely a waste of money.

Stimulus Checks Don’t Stimulate. They Also Don’t Help Those Who Need The Money The Most

Compounding the economic inefficacy of direct stimulus payments under current circumstances is the sobering reality that the payments themselves arguably do not even help improve the fortunes of those who need the money the most—the poor.

A recent study by Harvard University behavioral scientist Ania Jaroszewicz indicates that direct unconditional cash transfers (UCTs) to people living in poverty had little to no beneficial effect, either economically, physically, cognitively, or psychologically.

While the cash transfers increased expenditures for a few weeks, we find no evidence that they had positive impacts on our pre-specified survey outcomes at any time point. We further find no significant differences between the $500 and $2,000 groups. These findings stand in stark contrast to the (incentivized) predictions of both experts and a nationally representative sample of laypeople, who---depending on the treatment group, outcome, and time period---estimated treatment effect sizes of +0.16 to +0.65 SDs. We test several explanations for these unexpected results, including via two survey experiments embedded in our trial. The data are most consistent with the notion that receiving some but not enough money made participants’ needs---and the gap between their resources and needs---more salient, which in turn generated feelings of distress.

While we should always be careful of leaning too heavily on a single study, the lack of demonstrable benefits to the individual do line up with the lack of demonstrable efficacy at the macro-economic level.

The pandemic era stimulus checks didn’t stimulate much of anything, either for the individual or for the economy.

Nor is there any good reason to believe future stimulus checks from the Federal government would have any different outcome. While the Federal government only issued three UCT payments to individuals in 2020 and 2021, fourteen states have, on their own initiative, authorized and implemented their own UCT programs (i.e., “stimulus checks”) to various demographics within their borders.

The lack of efficacy of these payments is reasonably inferred from the same lack of upswing in nominal GDP seen in the graphs above.

Are These Stimulus Payments Producing Inflation?

A frequent criticism of direct UCT payments—especially from Congress—is that they increase inflation and incent workers to remain outside of the labor force.

McConnell opposed President Joe Biden's stimulus law, which passed with only Democratic votes in March 2021 after two previous rescue packages approved by the Trump administration. Republicans have long blamed that $1,400 direct payment to Americans for worsening inflation and helping keep people out of the workforce.

Is the inflation charge justified? This much is certain: the growth of the CPI since the 2020 recession largely occurred soon after the stimulus payments were made,

The rounds of stimulus UCT payments occurred in April of 2020, December 2020-January 2021, and in March of 2021. The initial burst of inflation began in May of 2020, and the major jump in inflation began in February, 2021, and continued on through that June. The timing of the payments and the rises in inflation do support the thesis that the payments in fact stimulated inflation rather than economic growth.

The notion that the stimulus payments have kept workers out of the labor force is a far more problematic proposition, although it is an enduring one, as Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell demonstrated this past Tuesday.

"You've got a whole lot of people sitting on the sidelines because, frankly, they're flush for the moment," the Kentucky Republican said. "What we've got to hope is once they run out of money, they'll start concluding it's better to work than not to work."

There is some data to support this proposition. The Moody’s Analytics “Weekly Market Outlook” from January 13, 2022, asserted that pandemic-era stimulus programs had resulted in some $2.6 trillion in “excess savings” by American households, which savings has to be spent for it to work through the economy.

Excess savings is expected to be gradually reduced over time, but it will end this year north of $2 trillion. Excess savings is currently around $2.6 trillion and is forecast to drop to $2.2 trillion by the end of the year. Reminder, excess saving is on top of what households would have saved if the pandemic had not occurred and their saving behavior had been the same as in 2019, before the pandemic. As a result, it is potentially available for spending.

With that much extraordinary savings in reserve, Senator McConnell’s statement about workers sitting on the sidelines is arguably plausible. However, there is a catch: most of that excess savings is held by people in the highest income brackets, not by people at or below the poverty line.

It is unlikely that huge amounts will be spent this year since much of the excess saving has been by high-income, high net worth, and older households. Many of these households are approaching retirement, or are already there, and having lived through the pandemic and the financial crisis may believe they have under saved, especially in the years leading up to the financial crisis. Hence, they are likely to treat the saving more like wealth than income. Wealth, even newfound wealth, is mostly held, not spent.

Also, the bulk of the excess savings is held by higher-income, older, more educated individuals with homes. More specifically, more than 70% of the excess savings is held by the top 20% of the income distribution and a similar amount is held by the college educated. Those aged 55 and older hold nearly 60%, with baby boomers holding almost half. Finally, homeowners are in possession of almost 90% of excess savings, with close to 85% among those without existing home equity lines of credit.

As is so often the case, one has to delve into the statistics to understand their true significance. Looking at the Moody’s Analytics top-level numbers, with a $2.6 trillion nest egg, it would not be at all surprising for savings of that magnitude to discourage workers from returning to the labor force. However, when one considers the demographics of whom is holding that $2.6 trillion, that narrative quickly vanishes. The consumers holding those excess savings are also the ones least likely to be in the workforce at all—wealthy and older individuals, including a number of retirees, who would not be in the labor force even without the pandemic-era lockdowns.

This is a significant argument against stimulus payments. In addition to their potential for encouraging inflation, it is essentially impossible for the government to target those payments with sufficient precision to ensure the monies flow to the people most in need of such assistance.

Moreover, it is not merely a question of direct assistance in the form of unconditional cash transfers that raises the specter of inflation. One of the concerns about the White House’ efforts to wipe out student loan debt is that, by removing large chunks of individuals’ debt burden, student loan forgiveness becomes the equivalent of a massive UCT payment program, with all the inflation-causing potential inherent in such a program.

But with the US facing 40-year-high inflation, that potential burst of new spending power from consumers who'd instantly see their net worth jump by thousands of dollars could send the cost of common goods and services even higher. Prices soared 8.6% in the year through May, powered by an abundance of consumer demand and woefully insufficient supply.

Regardless of the precise vehicle used to provide direct or indirect assistance to American households—UCT payments or debt forgiveness— the utility of such assistance in ending a recession is essentially nil, with the added complication of also stimulating inflation, something the US economy most certainly does not need!

Contrary To The Fed’s Plan For Inflation

While the idea of providing a measure of economic assistance to those in dire economic circumstance can be wrapped in all manner of good intentions, the unavoidable reality of such assistance is that it runs counter to the Fed’s plans for squelching consumer price inflation. Never forget that the Fed’s strategy for reducing inflation is to first suppress consumer demand.

Whether UCT payments will or will not cause further inflation, stimulating demand is the polar opposite of what the Federal Reserve intends to accomplish, which is demand destruction. That is their stated policy and their explicit objective.

Whether the current economic contraction is the specific result of the Fed’s interest rate hikes to date any effort to reverse that contraction would work to frustrate that objective. There can be no reduction in overall demand if the government is working to stimulate that demand. There can be no slowing down in hiring if the government is working to incentivize hiring. There can be no emphasis on saving when government is attempting to motivate spending instead.

Consequently, the government, much like the Federal Reserve, is caught between a fiscal rock and an inflation hard place.

The government can allow the Fed strategy for fighting inflation to play out—at the expense of a technical economic recession, rising unemployment, and reduced consumer demand.

Alternatively, the government can frustrate the Fed policy, work to stimulate demand and cut short a technical economic recession—at the expense of continued inflation.

The government cannot simultaneously support the Fed’s inflation-fighting strategy and stimulate the economy. The two objectives are, by the Fed’s own rhetoric, mutually exclusive.

The options for the Fed on fighting inflation: Heads the Fed doesn’t win. Tails the Fed simply loses.

The options for the government on fighting off recession: Heads the people don’t win. Tails the people simply lose.

“Winning” is not an option—for anybody.

That pension money sitting just out of their grasp must be killing them.

But, legislation inbound!

Any thoughts on this, Peter.

And, as usual, Superb work.

That stimulus research is interesting, I need to research this further.