Untangling Interest Rate Hikes

Why The Fed Responds To Economic Challenge By Futzing With Interest Rates

This post comes courtesy of a comment one of my readers made on my last article, “The Technical Recession Cometh”.

Reader Jim Marlowe wrote:

Are we back to thinking the federal funds rate is directly correlated with long term mortgage rates? I remember reading articles over the last 25 years explaining why that was not the case. They weren't all that clear in any case. But I do tend to believe that the two aren't directly correlated in a "normal" functioning economy. They used to say that mortgage rates were more correlated with long term treasuries.

Rather than delve into the topic in a direct response to his comment, I am turning that response into a stand-alone article. Jim asks some very important questions, and understanding both the dynamics and the politics at play is an essential context to grappline with the Federal Reserve’s actions—and mistakes—in monetary policy.

Interest Rates Are All Correlated

The first point to address is that there is a fairly strong correlation between the 30 year fixed rate mortage and the 10-year US Treasury yield, as well as a somewhat less strong correlation between the 30 year fixed rate mortgage and the federal funds effective rate. There is also a correlation between the federal funds rate and the 10-year Treasury yield, albeit one that is less than the correlation between the 30-year mortgage rate and the 10-year Treasury yield as well as one that is less than the correlation between the 10-year Treasury yield and the federal funds effective rate.

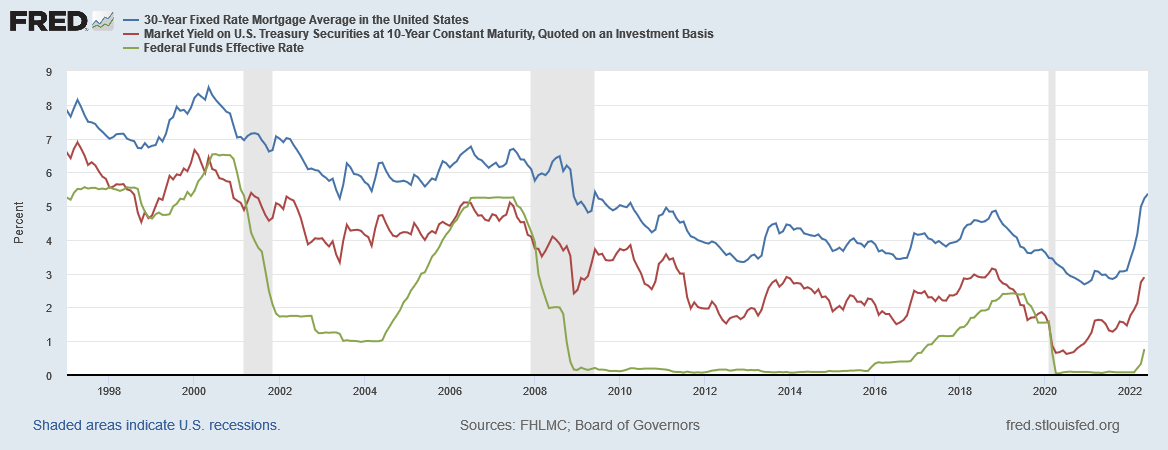

Looking at the Federal Reserve data on interest rates, we see that these three rates have varied since January of 1997 like this:

As the chart clearly shows, the 30-year mortgage rate and the 10-year US Treasury yield move almost in tandem, with the mortgage rate approximately 2-3 percentage points above the 10-year Treasury rate as a general rule of thumb. This near-constant variation illustrates the strong correlation between these two interest rates.

Yet there is also correlation between the 30-year mortgage rate and the effective federal funds rate: visually, we can see that mortgages decline when the federal funds rate declines, and rises again when the federal funds rate rises. Obviously, there a stronger correlation between 10-year Treasury yields and the 30-year fixed rate mortgage, but the interest rates broadly follow the same path.

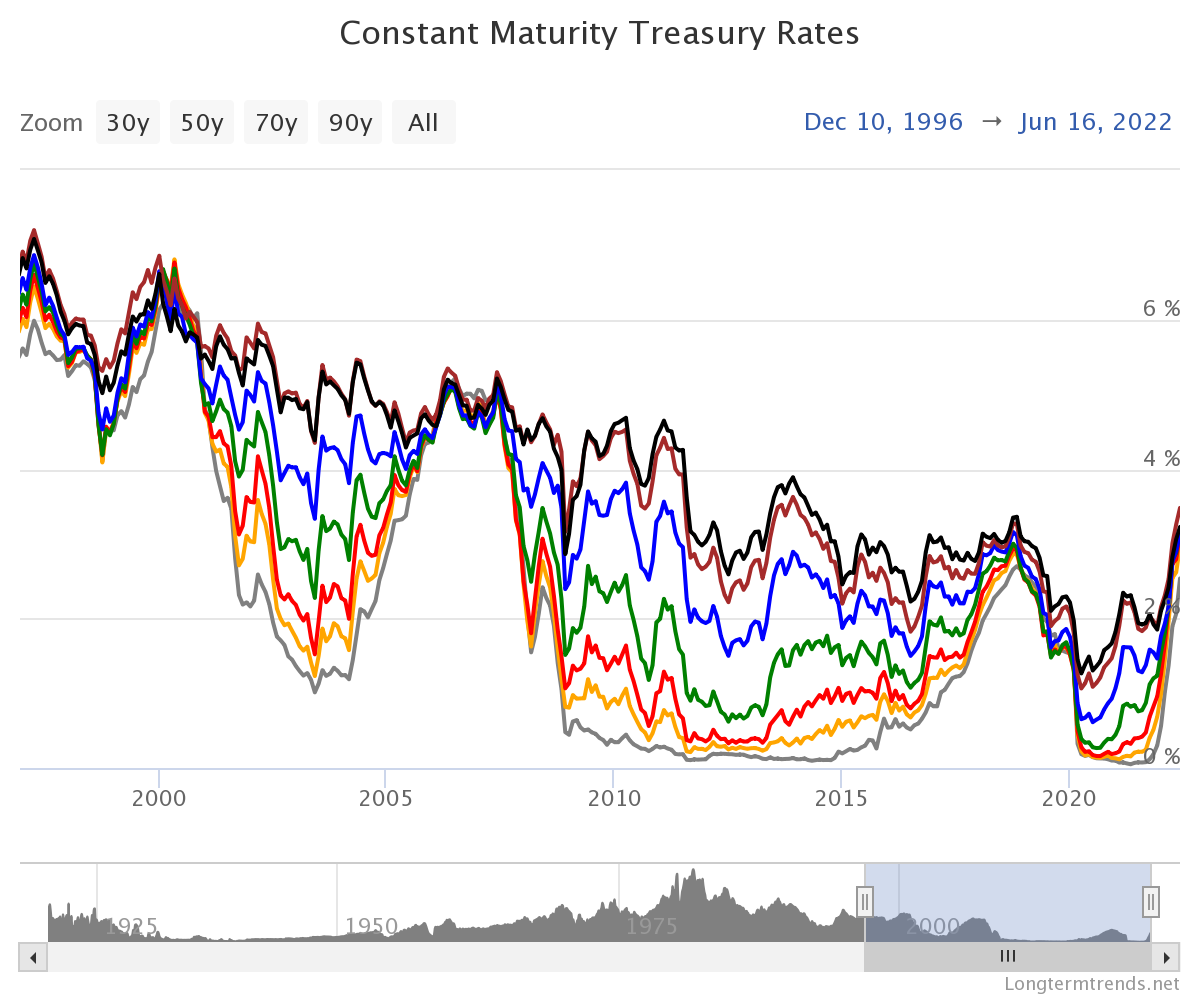

Given the patterns that we see on all Treasury yields, this interconnectedness is not at all unusual.

Broadly speaking, interest rates rise and fall in tandem. The magnitude of the shifts vary depending upon the underlying security, but the broad pattern is consistent across the whole range of US Treasury maturities.

Correlation Is Not Lockstep

However, while there is a strong broad correlation among the federal funds rate, the 10-year Treasury yield, and the 30-year fixed rate mortgage, correlation does not mean the rates move in lockstep with one another. Sometimes they diverge, which happened last week in the wake of the Federal Reserves 75 basis point (0.75%) hike in the federal funds rate.

Last week, the 10-year Treasury yield actually declined….

…while mortgage rates rose.

Why the divergence? The generic answer is simply “market forces”.

Ultimately, all of these interest rates with the exception of the federal funds rate—which the Federal Reserve manipulates more or less directly—are the result of securities markets at work. There are influences on all these rates outside of the federal funds rate, and it is the amalgamation of these forces that give us the rates we see tossed about in the financial media.

In the case of the 10-year Treasury yield, the declining yield indicates an increased demand for that particular security among investors (yields on debt instruments always moves in opposition to the instrument’s price: rising yields are declining prices and declining yields are rising prices). One possible explanation for last week’s decline in Treasury yields is investor approval of the Fed’s rate hike. If investors see the Fed’s moves as being broadly beneficial for US Treasury debt, it follows they would respond by buying more Treasuries.

Mortgages, on the other hand, arguably reacted to the tighter credit and money supply conditions the Federal Reserve is creating with its rate hikes, which in turn pushes up mortgage rates.

Why Futz With Interest Rates At All?

Recognizing the interconnected correlations among interest rates helps illuminate the Federal Reserve’s foundational logic for raising interest rates in response to rising inflation. Whether that logic is completely sound or appropriate to the current situation is a topic worthy of an article unto itself (and probably will be an article in the not too distant future!). For now, we will simply explore the prevailing thinking on interest rates and how they are believed to impact inflation.

While the reasons for inflation itself are varied and can be fairly complex, the phenomenon itself has a fairly simple description: current demand is exceeding current supply.

The Federal Reserve can do little to directly influence supply, of course, but it presumably can influence demand through interest rates. The logic here is twofold.

By pushing interest rates up, borrowing becomes more costly, thus less attractive, and thus borrowing becomes more limited the higher interest rates rise.

When interest rates are higher, saving money becomes more attractive. Thus, at higher interest rates, consumers are incented to postpone expenditures, which in turn reduces current demand.

As a consequence, the Federal Reserve uses interest rates to, in its view, “slow down the economy.”

But how do higher interest rates reel in inflation? By slowing down the economy.

“The Fed uses interest rates as either a gas pedal or a brake on the economy when needed,” said Greg McBride, chief financial analyst at Bankrate. “With inflation running high, they can raise interest rates and use that to pump the brakes on the economy in an effort to get inflation under control.”

Some economists also propose that interest rate hikes can address some supply chain issues through rate hikes. By moderating inflation in general, production and logistics costs within various supply chains in theory are also moderated, thus relieving some of the cost pressures producers are experiencing currently.

There could also be a secondary effect of alleviating supply chain issues, one of the main reasons that prices are spiking right now, said McBride. Still, the Fed can’t directly influence or solve supply chain problems, he said.

“As long as the supply chain is an issue, we’re likely to be contending with outside wage gains,” which drive inflation, he said.

The influence of interest rates on supply chains is problematic, however. Most economists are far more certain about the influence of interest rates on the demand side of the economy.

Thus, by raising interest rates, the Federal Reserve is attempting to push current demand down until it matches current supply for most goods and services, at which point inflation should abate.

Is The “Logic” Sound?

Given my assertions in previous articles that rampant inflation is actually a reduction in overall economic output, I wish to reiterate that this is the “prevailing wisdom” on the subject of inflation and interest rates. I will be dissecting this “wisdom” in future articles, but right now the point is to establish what the thinking actually is.

However, as a prelude to future explorations of this topic, it is worth contemplating broadly the validity of the Federal Reserve’s logic on inflation.

Is inflation actually an expression of “too much” economic activity—i.e., is the economy really growing at too fast a rate? Does GDP growth over the past three years—starting before the significant rise in inflation per the Consumer Price Index—show elevated growth in recent quarters? You tell me.

Alternatively, as a growing economy presumably is pulling workers back into the workforce, has there been a significant increase in the labor force participation rate recently? You decide.

Suffice it to say, the data invites certain challenges to the prevailing logic behind the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes.

Which leads me to an observation another of my readers made:

So there is a recession, but they don't admit it & raise interest rates until they decide to admit it & lower interest rates again.

While Mary’s description is perhaps somewhat of an oversimplification, it must be noted that her assessment—and her cynicism—have more than a little merit. If the Fed’s logic is unsound (again, look at the graphs above to see if their logic fits what their data shows about the economy), then their approach is almost certainly unsound as well.

Sound or unsound, however, this is the Federal Reserve’s approach to stopping and ultimately reducing inflation. How well this approach will work under current economic circumstances is a tale that is being told even now. What the costs—and the unforeseen consequences will be—we can somewhat project, but even those are still unfolding before us.

Rate hikes are the path the Federal Reserve has chosen. Regardless of whether the Fed has chosen well, the consequences of that choice will unfold however they will. We shall soon see if those consequences constitute good news or bad.

> The generic answer is simply “market forces”.

Except that actions like QE and QT (if the Fed ever really does the latter) are major market distortions. Interest rates have been artificially low since 2008/2009, and arguably since 2001.