If there is one sector of the US economy that absolutely screams “RECESSION!” it is the US housing market.

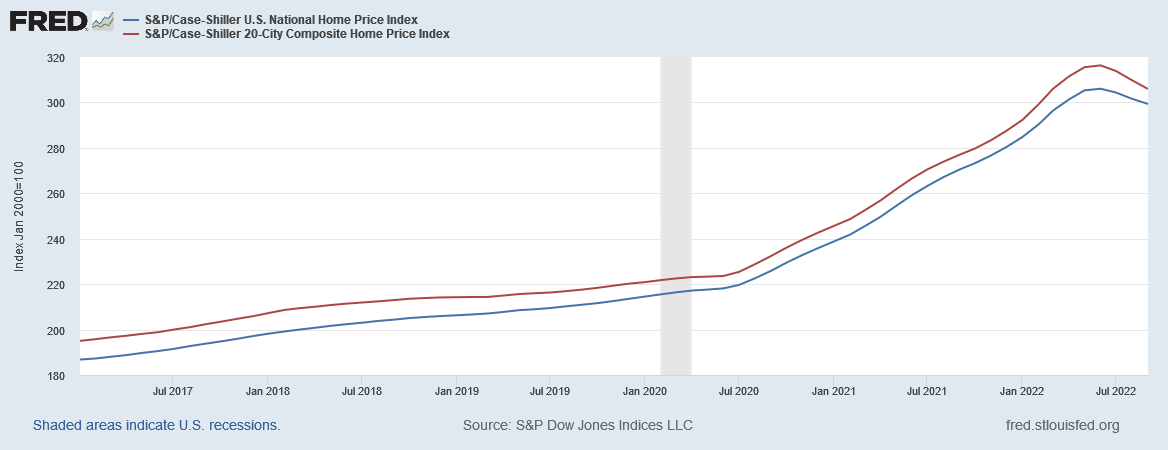

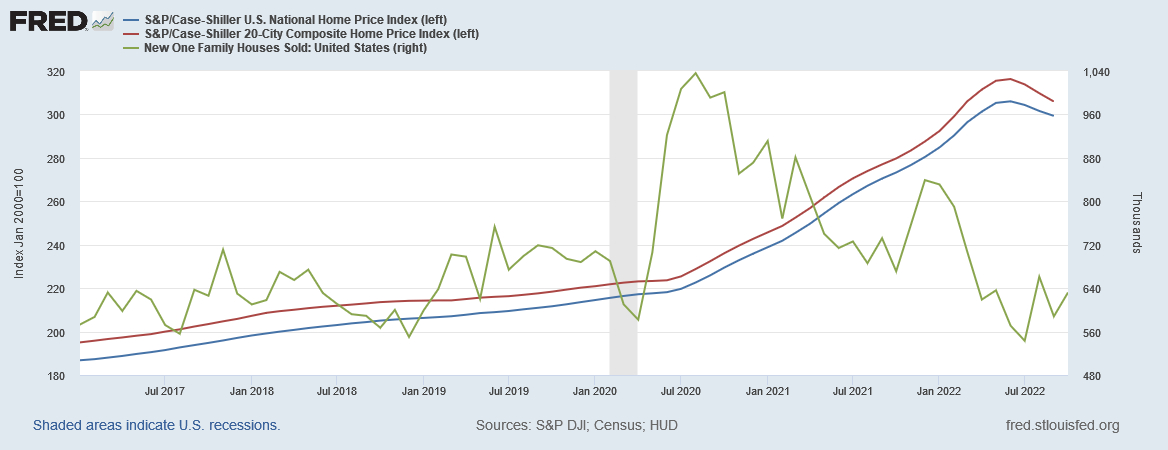

How bad is the housing market? Bad enough that in September the Case-Schiller Home Price Index declined for the third month in a row.

The S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. 20-city price index fell 1.2% in September, its third consecutive monthly decline.

The decline matches the forecast of economists were expecting a 1.3% decline.

Year-on-year appreciation rose 10.4%, but that reflects the stronger conditions in late 2021. The figure is down from 13.1% in August.

A broader measure of home prices, the U.S. national index, fell by a seasonally adjusted 0.8% in September.

Both the 20-city index and the broad national index have dropped by several points, indicating that home prices are on the decline across the country.

Put simply, housing markets in the United States are collapsing. Housing markets are not merely cooling off, which would be an apt description if the rate of price growth in the index was the substance of the decline, but are contracting everywhere, leading to the absolute decline within the index itself.

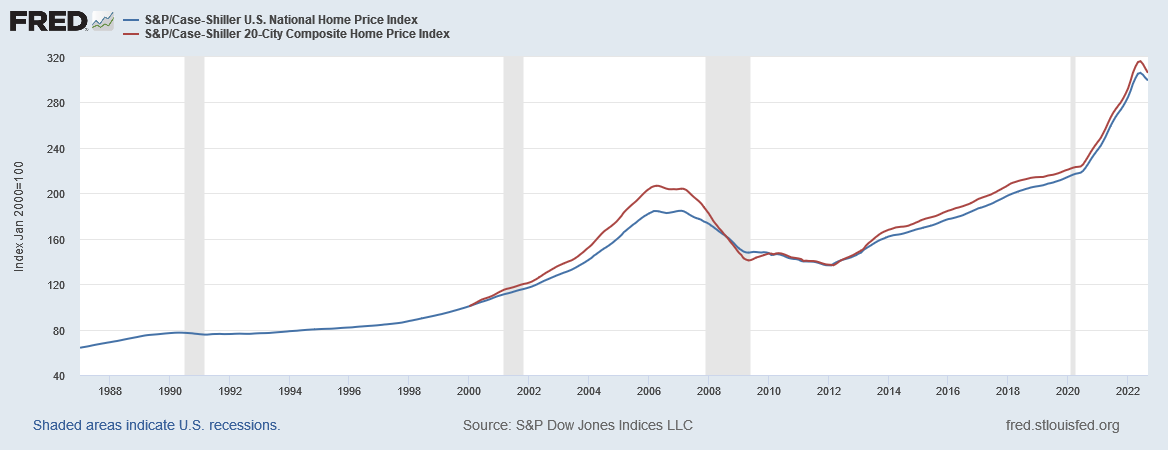

The summer drop in the Case Schiller index is the first decline in the index since the aftermath of the 2008-2009 recession, and only the second one since the index began in 1987.

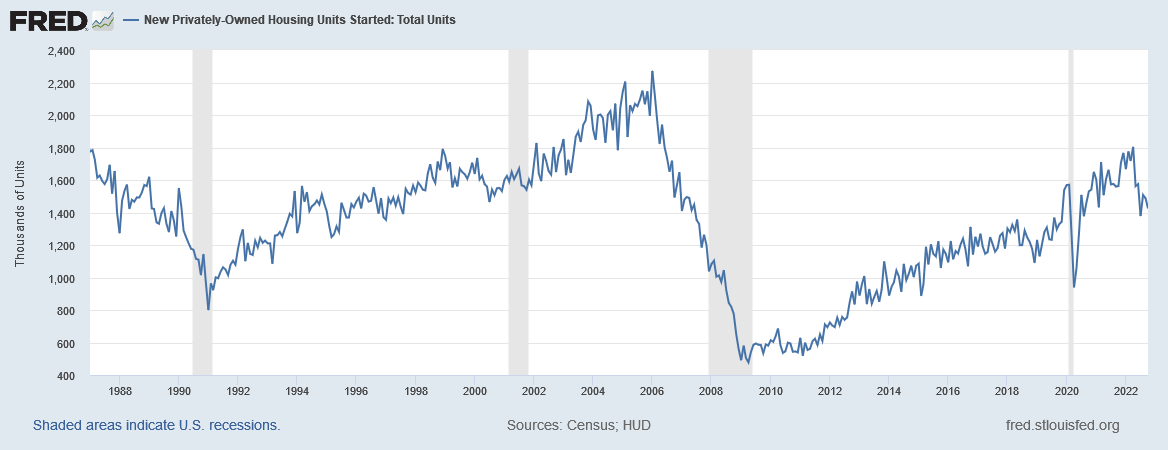

Nor is it merely the housing prices themselves that are in decline. Privately-owned housing unit starts are dropping as well, even though housing starts had yet to reach the same levels as before the 2008-2009 recession.

These are not merely signals of a looming housing recession, but confirmation of it. These are indicators of the depth of the contraction US housing markets are undergoing—and they do not indicate that the contraction is at all finished.

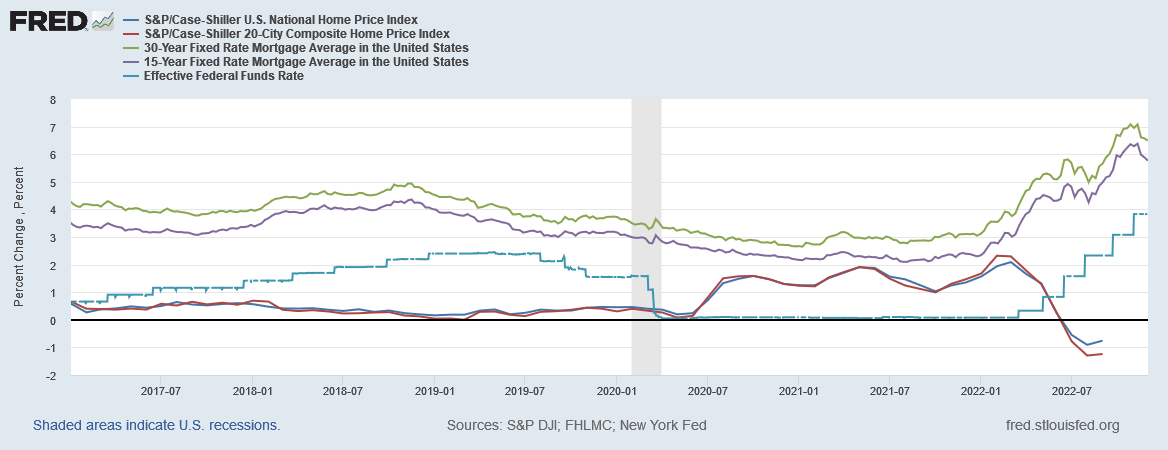

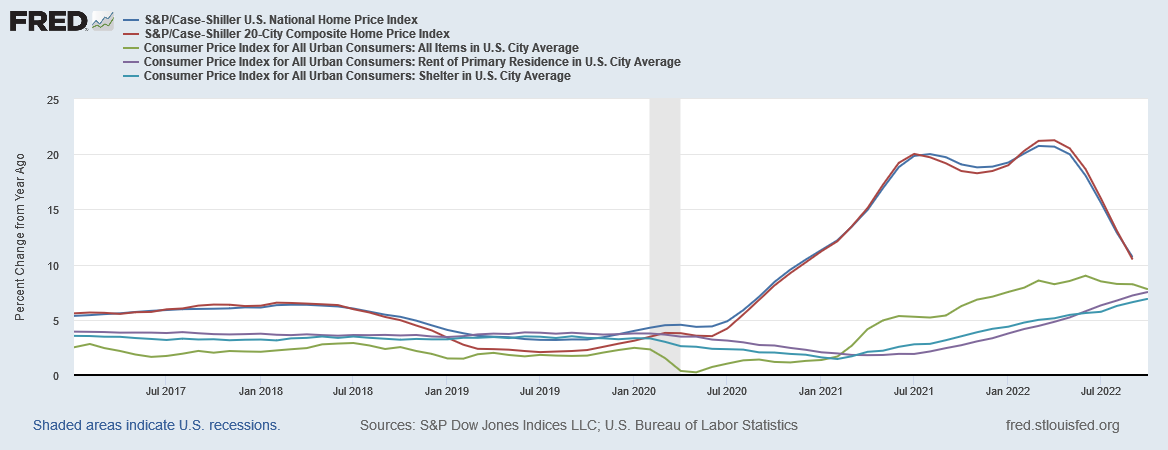

Nor do we need to look far to find the catalyst for this contraction: the alignment among the percentage decline in the Case Schiller index, mortgage interest rates, and the rise of the Federal Funds rate gives a very clear signal that the decline is almost entirely attributable to the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes.

Mortgage rates have been far more responsive to the Fed’s rate hikes, and as mortgage rates have risen, the monthly percent change in the Case Schiller index has dropped, eventually moving negative—the Case Schiller index began declining—as mortgage rates exceeded 5%.

Jay Powell has apparently succeeded in destroying the demand for new housing.

This particular demand destruction has been a mixed blessing. The year on year percent rise in the Case Schiller index shows there has been a definite bubble in housing that has finally burst, and now housing prices are returning back to more normal levels.

The existence of a housing bubble is confirmed by the decline in new home sales as the Case Schiller index surged.

Given the bubble’s contribution to overall consumer price inflation, deflating the bubble is ultimately an economic positive.

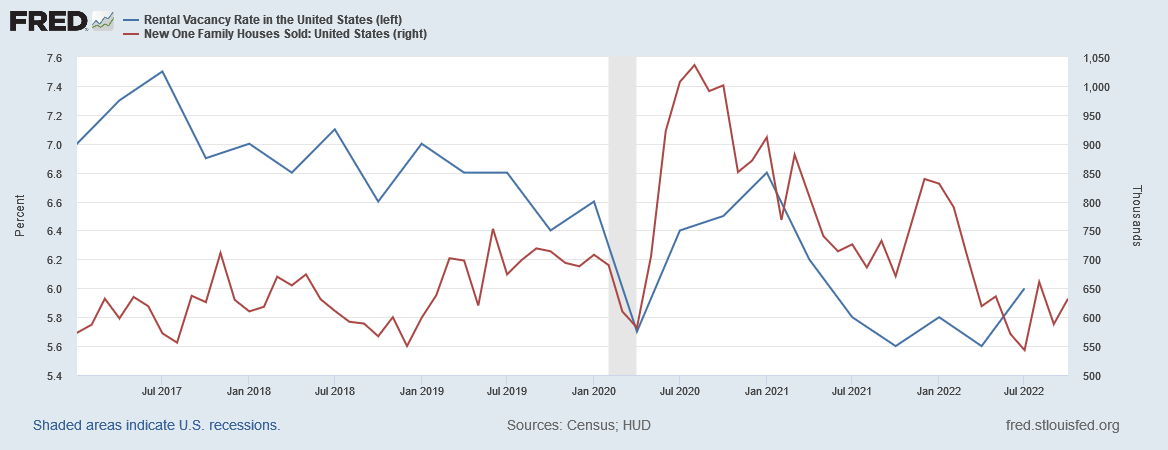

However, until there is clear recovery in housing starts, the decline in housing sales means more people are still renting rather than purchasing. The contraction of the housing market is still producing sustained upward pressure within the shelter price component of the CPI—people have to live somewhere.

The contribution of the housing market’s contraction towards rising shelter price inflation is confirmed by the post-pandemic alignment between the declines in new home sales against the declines in rental vacancy rates.

Shelter price inflation is thus not ending or even peaking just because the Case Schiller index has peaked and is moving back towards a sustainable long term trend.

Because the contracting housing market is not bringing any relief to shelter price inflation in the US, the housing market recession is leading the overall economy deeper into recession. The lack of housing demand is placing supply-side pressure on rental properties by reducing vacancy rates, effectively diminishing the supply of available rental properties.

Paradoxically, given the responsiveness of mortgage rates to hikes in the Federal Funds rate, the Fed’s rate hikes are likely to keep mortgage rates high and may even push them higher, reversing their recent declines, which in turn will suppress new home sales—and thus contribute to a continued lack of supply of rental properties, meaning the upward pressures in shelter price inflation are not merely not remedied by interest rate hikes, but may even be aggravated by them.

Over the short term at least, the Fed is actually causing shelter price inflation, rather than ending it.

WIth the Fed not set to end its rate hikes any time soon, it is unlikely the housing market will find its bottom any time soon and begin moving into a recovery. Rather, the housing markets will continue to slide into a deeper recession, and continue to both push shelter price inflation (and potentially overall consumer price inflation) higher, continuing to lead the overall economy into an even deeper recession as well.

Things are likely to get worse before they get any better.

Case-Shiller is still at ~300. IMO, anything over 200 is bubble territory, meaning we have a long way down. It wouldn't surprise me if we hit 150 before this is over, but it will take a number of years to get there.

Why do you think we had such a dramatic increase in house prices during the covid "pandemic" period from 4/20 through 6/22? Is some of the reduction now just a correction?