What Happened? Labor Department Reports Weak Job Growth

Government Job Stats Nowhere Near ADP Report

Wednesday's ADP National Employment Report was undeniably positive, with some 800,000 jobs added to private sector payrolls.

Today's Employment Situation Report by the Labor Department fell far short of that mark, showing only 119,000 jobs were added last month, even as the unemployment rate dropped down to 3.9%

Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 199,000 in December, and the unemployment rate declined to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Employment continued to trend up in leisure and hospitality, in professional and business services, in manufacturing, in construction, and in transportation and warehousing.

What happened? How could the two numbers vary so widely?

New Jobs Or Just Job Churn?

One possible explanation for the discrepancy is simply job churn. To repeat the observation from Forbes magazine, the ADP numbers may have been pumped up by people leaving one job for another.

The JOLTS report also showed a decrease in job openings in November. The Great Resignation continues as the “quits” rate remained high. In the light of Wednesday’s ADP report, it may be that workers were simply quitting one job to take another job. Friday’s Employment Situation report could provide greater insights to these job market developments.

The comparatively weak Labor Department numbers would be in line with that happening.

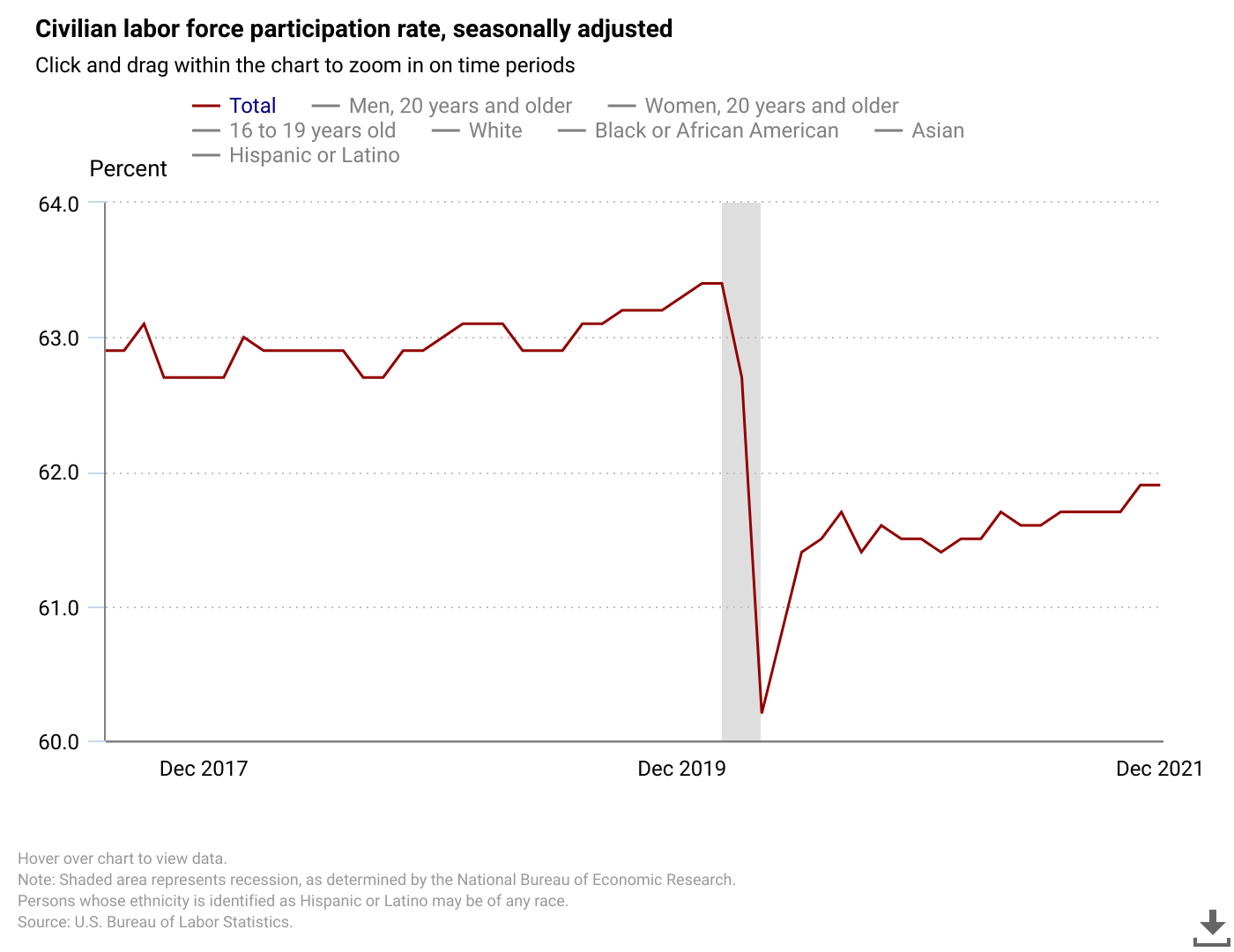

The labor participation rate seems to confirm this, as it remained unchanged at 61.9% (November's rate was revised up from 61.8%).

Once again, employers failed in December to bring substantial numbers of workers back into the workforce.

Top-level Number Hides Lack Of Growth

While the government numbers do show some incremental improvement in December, several subsets showed little or no improvement. In particular, several sectors were largely left out of December‘s jobs gains.

In December, employment showed little or no change in other major industries, including retail trade, information, financial activities, health care, other services, and government.

There was no improvement in the number of people not in the labor force who want a job.

The number of persons not in the labor force who currently want a job was little changed at 5.7 million in December. This measure decreased by 1.6 million over the year but is 717,000 higher than in February 2020. These individuals were not counted as unemployed because they were not actively looking for work during the 4 weeks preceding the survey or were unavailable to take a job.

Nor was there improvement in the number of “marginally attached workers”.

Among those not in the labor force who wanted a job, the number of persons marginally attached to the labor force was essentially unchanged at 1.6 million in December. These individuals wanted and were available for work and had looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months but had not looked for work in the 4 weeks preceding the survey. The number of discouraged workers, a subset of the marginally attached who believed that no jobs were available for them, was also essentially unchanged over the month, at 463,000.

The number of people forcibly sidelined due to COVID-19 was also unchanged.

Among those not in the labor force in December, 1.1 million persons were prevented from looking for work due to the pandemic, little changed from November. (To be counted as unemployed, by definition, individuals must be either actively looking for work or on temporary layoff.)

While these people are technically not in the labor force, and thus technically not unemployed, they are still people who want to work; they are simply encountering obstacles to employment. Many have grown discouraged and simply given up finding a regular job.

An economy which is not bringing these people back into labor force is an economy showing at best uneven and problematic growth. Given that the majority of such sidelined workers were thrust out of the labor force during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns, until they are restored to employment, the extent to which the economy can claimed to have recovered is equally problematic and uncertain.

Economies Need Workers

In every economic system imaginable, the more that people are working, the less stress there is on the social safety net. More workers with paychecks means more people able to support themselves without government assistance, and more people paying taxes to help fund that assistance. More people with incomes means more people able and willing to buy and consume goods and services. These things were true when Adam Smith wrote Wealth of Nations and they are true today.

Moreover, as I have pointed out in the past, recession and economic privation carry their own mortality burden. As has been recently reported, all cause mortality is up a staggering 40% from pre-pandemic levels among those age 18--64.

While it would be extravagant to ascribe all that excess death to the aftereffects of the pandemic-induced 2020 recession, it would be equally absurd to pretend such aftereffects are not a likely contributing factor to the mortality rise among working age people.

The United States needs people to be working. There is no avoiding that basic economic and social truth.

As the COVID-19 pandemic winds down, people in this country are returning to work, but not nearly as fast as they need to be.