What Size Is The Next Shoe To Drop?

Commercial Real Estate Exposures Loom Large....But For Whom?

With First Republic Bank and Deutsche Bank still flirting with disaster, one question that invariably must be asked is “what’s next?”

What is the next economic shoe to drop, and who will have been wearing it?

As is always the case with future events, nothing will be known for certain until that next shoe does drop, but the dynamics of financial markets do tell us where vulnerabilities are increasing, and which could precipitate a next phase of financial and economic crisis.

One of the biggest vulnerabilities that is emerging appears to be in commercial real estate. Certainly Bank of America analyst Michael Hartnett seems to think so—and with reason.

The next domino to fall in the ongoing banking crisis could be commercial real estate loans, according to a Friday note from Bank of America.

A potential credit crunch in the sector, sparked by a wave of upcoming refinancings of commercial real estate loans at much higher interest rates than in the past, could send stocks spiraling and the economy into a recession.

"Commercial real estate [is] widely seen as next shoe to drop as lending standards for CRE loans to tighten further," Bank of America's Michael Hartnett said.

In what could be a replay of the 2007-2008 subprime mortgage crisis, commercial real estate debt could be facing a looming default risk as distressed CRE markets collide with 2023 interest rates.

There are two key factors that are driving up the potential for commercial real estate debt defaults in 2023:

Office occupancy rates suck. Prior to the COVID pandemic, office occupancy rates in the United States were hovering around 95% nationwide. Today, office occupancy rates are approximately half that. In the haste to “flatten the curve” as evangelized by the Pandemic Panic Narrative, companies large and small embraced a standard of “work from home” for many of their office staffs. Company meetings were replaced by Zoom videoconferencing, and company offices became ghost towns.

Before the pandemic, 95% of offices were occupied. Today that number is closer to 47%. Employees' not returning to downtown offices has had a domino effect: Less foot traffic, less public-transit use, and more shuttered businesses have caused many downtowns to feel more like ghost towns. Even 2 1/2 years later, most city downtowns aren't back to where they were prepandemic.

While the Pandemic Panic Narrative has collapsed and largely faded from sight (thankfully!), office workers have been reluctant to return to the office. A home office is apparently much more comfortable than a cubicle (shocking!), and workers have responded to calls by corporate management to return to the office with a general shrug and the question “why?” The result has been a drastic increase in vacant offices and vacant office buildings.

Not unlike how deindustrialization led to abandoned factories and warehouses, the pandemic has led downtowns into a new period of transition. In the 1920s factories were replaced by gleaming commercial high-rises occupied by white-collar workers, but it's not clear yet what today's empty skyscrapers will become. What is clear is that an office-centric downtown is soon to be a thing of the past. With demand for housing in cities skyrocketing, the most obvious next step would be to turn empty offices into apartments and condos. But the push to convert underutilized office space into housing has been sluggish.

Empty real estate is generally less valuable than occupied real estate, which all on its own is a stressor for commercial real estate financing.

The second factor is that corporate interest rates—just as with treasury yields, began rising even before the Federal Reserve began hiking the federal funds rate in March of last year. Effective yields on BBB-rated corporate debt (the lowest “investment grade” debt rating) are higher now than at any time since July of 2010 (with the exception of brief spike during the dislocations of the government-ordered 2020 recession).

These two factors combined present a major hurdle for refinancing of commercial real estate debt, which means that, as that debt matures, it must either be repaid or there will be a default.

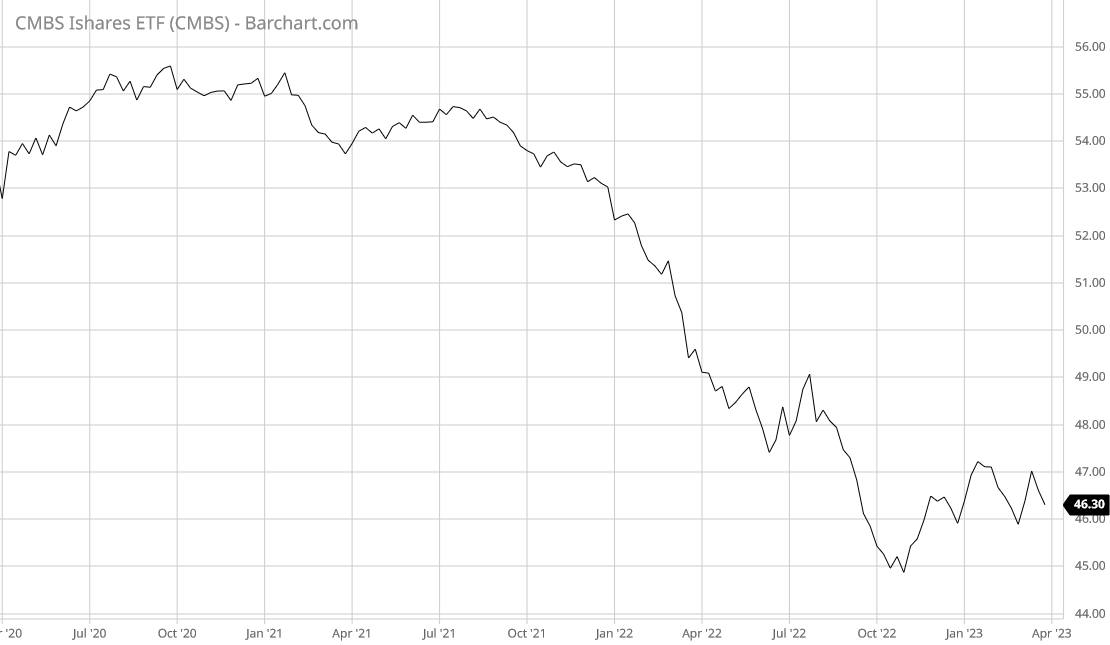

That commercial real estate as well as CRE debt has lost significant market value over the past year is easily seen in market data. The IShares CMBS Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) has been steadily shedding value since early 2021.

The decline in the overall value of real estate investments can easily be seen in the decline of the Dow Jones Equity All REIT Index (REIT is short for Real Estate Income Trust, a common market vehicle for investing in real estate). The DREI index peaked in late December of 2021 and has declined ever since.

With some $450 billion in commercial real estate loans maturing in 2023, these market forces present a powerful case for a rise in defaults on commercial real estate loans and mortgages.

There's nearly $450 billion in commercial real estate loans that are maturing in 2023, and about 60% of them are held by banks, according to a recent note from JPMorgan that cited data from Trepp.

Analysts at JPMorgan are projecting a substantial wave of CRE debt defaults beginning this year and extending through the next several years, as outstanding loans come due and are either paid off, successfully refinanced, or succumb to default.

"We expect about 21% of commercial mortgage backed securities outstanding office loans to default eventually, with a loss severity assumption of 41% and forward cumulative losses of 8.6%... Applying the 8.6% loss rate to office exposure, it would imply about $38 billion in losses for the banking sector," JPMorgan said.

With 60% of CRE loans held by (small) banks, and an 8.6% default rate for CRE loans, what is the impact on banks for 2023?

The short answer is “not good.”

Commercial Real Estate debt has long been a forte of the small banking sector in the US. At present, large banks in the US hold some $842 Billion in CRE loans, but small banks hold more than double that at $1.96 Trillion.

As of the latest data, 70% of commercial real estate loans are held by small banks.

Yet even if we look at just the 60% figure used by JPMorgan’s analysts, that still equates to some $270 Billion of CRE loans held by smaller banks which are maturing and coming due this year, with $180 Billion being held by larger banks. An 8.6% default rate on that $450 Billion of maturing CRE debt translates into losses to the small banking sector of $23 Billion, and $15 Billion to larger banks.

Is JPMorgan’s analysis reliable? Again, we mus consider the data.

Since the start of 2022, the CMBS ETF has lost 11.5% of its market value, which shows that investors are nervous about something, and a debt default would certainly qualify.

JPMorgan’s 8.6% default rate assessment is thus probably on the conservative side—arguably one can assess the market at pricing a default rate of 11% or higher.

The impact to smaller banks of a wave of CRE debt defaults would not be good. In recent years, CRE loans comprise more than 28% of smaller banks’ total assets, and while that percentage declined in 2020 and 2021, in 2022 that percentage reasserted itself.

An 8.6% default rate among an asset class that makes up 28% of the proto-typical “small bank’” total assets would be a substantial reduction in assets, in a year when investors and depositors are not likely to be forgiving about such things.

However, that is not the only exposure for rising CRE debt defaults. In fact, we may already have a preview of how these defaults might unfold.

At the beginning of March, Blackstone, a private equity firm specializing in real estate and owner of the largest non-listed REIT, defaulted on a $562 Million bond secured by a portfolio of Finnish properties.

The private equity firm had sought an extension from holders of the securitized notes to allow time to dispose of assets and repay the debt, according to people with knowledge of the plan. Market volatility triggered by the war in Ukraine and rising interest rates interrupted the sales process and bondholders voted against a further extension, the people said, asking not to be identified as the sales process was not public.

Blackstone achieved some notoriety last fall when it limited redemptions from its REIT investment vehicle.

Blackstone Inc (BX.N) limited withdrawals from its $69 billion unlisted real estate income trust (REIT) on Thursday after a surge in redemption requests, an unprecedented blow to a franchise that helped it turn into an asset management behemoth.

The curbs came because redemptions hit pre-set limits, rather than Blackstone setting the limits on the day. Nonetheless, they fueled investor concerns about the future of the REIT, which makes up about 17% of Blackstone's earnings. Blackstone shares ended trading down 7.1% on the news.

However, much as was the case with Silicon Valley Bank, concern over Blackstone did not arise suddenly last fall, nor this month with the bond default. The real estate asset giant’s share price peaked near the end of 2021 and has been in decline ever since.

Redemptions from its REIT vehicle, much like runs on deposits at a bank like SVB, are indicative of a growing crisis of confidence in their real estate portfolio—and unlike a bank, REITs often have the option of blocking redemption requests, particularly if they exceed pre-determined amounts.

Bear in mind that a “liquidity crisis” occurs when cash to honor redemptions is not where it needs to be—i.e., when the bank or other institution does not have the cash on hand to process the redemption request. REITs blocking redemption requests lack the high drama of a bank run, but the fundamental dynamic is still very much in play: people can’t get at their money.

Bear in mind also that the Dow Jones Equity All REIT Index has been shedding value for approximately the same time frame that Blackstone stock has been declining. Regardless of how real estate prices may fluctuate, the overall trend for the market valuation of real estate investments has been one of extended decline—and continuing decline. This is not an investment sector that is well positioned for receiving significant flows of bad news.

At the time of the $562 million bond default, Blackstone still was limiting redemptions and curtailing outflows from its REIT.

Blackstone Inc (BX.N) said on Wednesday it had blocked investors from cashing out their investments at its $71 billion real estate income trust (BREIT) as the private equity firm continues to grapple with a flurry of redemption requests.

BREIT said it fulfilled redemption requests of $1.4 billion in February, which represents only 35% of the approximately $3.9 billion in total withdrawal requests for the month, the firm said in a letter to investors.

More than half of investors wanting to cash out of Blackstone’s REIT were summarily told “No”, while at the same time it stiffed creditors expecting their notes to be redeemed with cash.

No cash to investors, no cash to creditors…this does not sound at all good, does it?

Nor is BREIT unique. The $15 Billion Starwood Real Estate Income Trust (SREIT) also began limiting investor redemptions last December.

REITs are historically considered to be fairly illiquid investments, but in recent years alternative exchanges such as LODAS Markets have emerged as secondary exchanges where REIT investors can find alternate means of converting their investments into cash.

Starwood Real Estate Income Trust (SREIT) fund is now trading on the LODAS Markets platform, which was previously known as Realto and focuses on secondaries.

SREIT limited investor withdrawals in December 2022 and January 2023, leaving many investors scrambling for a way to convert their assets in the $15 billion fund into cash.

LODAS Markets began life as Realto, an alternative exchange which received SEC approval in January, 2022, as a means to provide liquidity to otherwise illiquid investments such as in REITs.

Realto’s aim has been to offer investors daily liquidity opportunities that to date haven’t existed via the secondary trading of real estate and other illiquid securities. In January, Realto received approval from the SEC to operate an Alternative Trading System (ATS), which allowed the firm to offer additional secondary trading opportunities via enhancements such as additional order types and two-sided quotes, according to officials.

However, a secondary exchange where investors can sell off notionally illiquid investments such as REITs for cash is merely an extended game of investing musical chairs. If REITs begin defaulting on their CRE loans, it does not take a rocket scientist to see that the value of individual REITs will decline, as will their assets. Whichever investor is the last one holding a REIT investment should the REIT portfolio suddenly lose value is exposed to huge losses.

While REITs like Blackstone and Starwood may not be publicly traded, it is most unlikely that even on a secondary market their valuation trend would be much different than those REITs which are publicly traded, and which we already know are generally losing market value.

As the press announcement from when the Starwood REIT began trading on LODAS indicates, the reason it is trading on this alternative exchange is because investors are not being allowed to pull their money out. LODAS itself acknowledges this is the reason for its very existence.

LODAS is an online marketplace where your clients can trade alternative investments – including non-traded REITs – similar to how they would a company stock.

The marketplace operates like an exchange where investors can buy when they want to buy and sell when they want to sell. They don’t have to wait for a sponsor’s redemption program to come through. Sellers set the share price they’re willing to accept from another buyer.

It’s liquidity on demand and on their terms.

On the one hand REITs are raising funds, taking in cash, while denying redemption requests. On the other hand, at least one REIT has already stiffed creditors, and if, as JPMorgan anticipates, this becomes a trend, we have an industry wide phenomenon where there’s no cash to investors and no cash to creditors.

Gee, what could possibly go wrong?

Here’s a hint, also from the LODAS press materials (emphasis mine):

There are about 30 active funds on LODASMarkets.com – including BREIT and SREIT. With millions of dollars of institutional buy-side interest, it’s a potential liquidity lifeline for all investors – especially those stuck in a months-long redemption cycle.

It’s just a hunch, but I’m guessing all that “institutional buy-side interest” has other funds sitting elsewhere….like in a bank (large or small). Funds that will have to be tapped to deal with whatever fallout emerges from a failed REIT investment or two.

That REITs are headed into rough financial waters is conceded even by the optimists regarding the state of commercial real estate investment.

“I expect a major correction in commercial real estate is already under way,” said Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

The expectation of economists such as Posen is that the inevitable correction in commercial real estate will have limited macroeconomic effects, because the bulk of the immediate effects would be contained to REITs and similar non-bank financing vehicles.

A disproportionately large share of the lending in commercial real estate went through so-called shadow banks. That these private-equity lenders aren’t banks may make the situation less threatening to the entire economy.

However, this view ignores the immediate contagion effect already identified by JPMorgan in the CRE loan portfolios which are a substantial at-risk investment by smaller banks in the US. That there are contagion effects beyond that are a virtual certainty.

We can see the shape of the likely contagion effects by looking at the established trends between the publicly traded REITs and various exchange traded funds for Mortgage-Backed Securities, including the State Street SPDR ETF in addition to the CMBS ETF mentioned previously. Broadly, they are all declining along the same trend lines, with largely matching rises and falls.

The trend for one is the trend for all. REITs are losing value faster than ordinary MBS funds, but a collapse in the value of REITs is likely to entail further decline in the market value for ordinary mortgage-backed securities, which are a significant asset class even for large banks.

We should note that mortgage-backed securities are a larger portion of the asset base for larger banks now than even in the run-up to the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, while being a smaller portion of the asset base for small banks.

Not only are long-dated treasuries a problem for banks in terms of declining market value, but it is almost guaranteed that mortgage-backed securities as well are poised to become an even larger problem for banks, especially if the predicted wave of CRE defaults comes to pass in even a small degree.

Which means that the network effects of a wave of CRE debt defaults is not going to be limited to small banks, but is going to ripple through all banks. The liquidity issues that would arise from a series of REIT setbacks almost certainly would not be contained to just the banks involved in the defaulted loans. The stage is set for a rampant contagion effect across the banking industry.

Just as in 2008, when rising subprime mortgage defaults were revealed to be just the tip of a large iceberg, rising CRE debt defaults are likely also to prove to be the tip of a very large iceberg, one which will hit more than just small banks.

Compounding this huge problem is crime. The pandemic years plus the leftist activism has resulted in empty commercial real estate in many downtowns, now plagued with drug-addicted homeless and associated crime. Everyone has heard about the tens of thousands of homeless in San Francisco, with their drug needles scattered everywhere, right? The same situation is now in many US cities, to a lesser extent, but just as entrenched. The cities’ governing bodies have been taken over by left-leaning people who will need to address crime before being able to revive the downtowns - but they are philosophically loath to take any of the hard measures necessary to end this crime! So any remedy is likely to take a long time, and meanwhile, all of the problems of devalued REITs you discuss will come true. I think we’re in for a long long recession.

As always, I so appreciate your efforts to give us hard data and sound analysis, Mr. Kust...

Indeed, barring a literal miracle of miracles, we are in for a very rough ride and a very hard landing in the very near future.