As I have observed on more than one occasion, perhaps the most important question when analyzing data is "does this make sense?". The data must completely explain an hypothesis or narrative, or there is more research yet to be done. The hypothesis or narrative must completely account for all the data (even if only to identify a data point as an outlier and not indicative of a broader trend) or it must be revised so that it does.

This is the basis of all scientific inquiry, the foundation of all diagnostic disciplines, including those that have informed my more than 25 years as a Voice and Data Network Engineer. If things do not make sense, the analysis is not yet complete.

When we attempt to assess the current state of the global CCPVirus pandemic, the data simply does not make sense.

Germany: Fun Is Banned Until 2023?

Our first entry in the list of things about CCPVirus that do not make sense comes from Germany, where Professor Hendrick Streeck suggests that house parties and large gatherings must be prohibited until at least 2023, as the number of CCPVirus infections is still far too high.

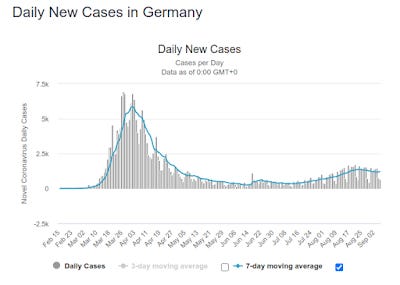

Professor Streeck asserts this even as CCPVirus cases in Germany peaked months ago and have been declining ever since, and are but a fraction of what they were:

Even Germany's "second wave" of infection has been minor compared to the original outbreak, and peaked around the middle of August.

'This virus is not disappearing. It has now become part of our daily lives,' he told the Daily Record.

'It will still be here in three years and we have to find a way to live with it.'

Yet, looking at Germany's case trends, at least that country has already found a way to live with it. If one looks at the mortality trend for CCPVirus in Germany, it seems even more apparent that an accommodation has been reached.

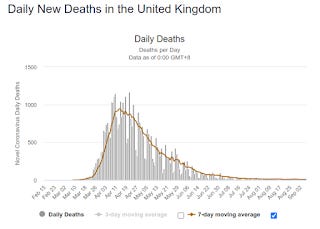

Even in the UK, where cases have recently begun to creep up, the mortality data so far continues to trend exceedingly low.

While no one ever wishes to be ill with so much as a cold, the lack of mortality in the UK even as case counts trend upwards begs the question of where the pandemic crisis lies. Depending on how much further the UK cases trend up, they are already arguably in the "post peak period" as defined by the World Health Organization. Germany would seem to be in the "post pandemic period," going by WHO metrics.

Yet Professor Speeck believes further lockdown measures are necessary?

How does that make sense? The extant data does not support that narrative.

Sturgis: The Super-Spreader Non-Event

As happens every year, the coming of August means only one thing to the residents of Sturgis, South Dakota: The Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, which can attract as many as 250,000 motorcycle enthusiasts from around the country. This year, naturally, the legacy media did the usual fretting over the rally's potential to be a "super-spreader" event.

This year’s festival may attract about 250,000 people despite an uptick in coronavirus cases across the state, city officials say, leading to fears it could become a super-spreader event.

Following the rally, the usual "experts" trotted out a study showing the rally was indeed a mecca for spreading CCPVirus, attributing an astronomical 260,000 cases to the rally.

The Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in South Dakota has been linked to more than 260,000 coronavirus cases in the U.S., according to a recent study by a group of economists.

However, the study did not use any form of genomic analysis of confirmed CCPVirus cases. Rather, the assessment by the study's authors was achieved by analysis of cell-phone location data, and correlating cell phone movements with various fluctuations in CCPVirus cases elsewhere in the United States.

While the cell phone data allowed the economists to get a sense of where rally-goers were coming from and what activities they participated in, data from local health officials and the CDC could help paint a clearer picture of how many coronavirus cases are likely connected to the Sturgis Rally, Sabia said.

Synthetic control models examining counties' COVID-19 trends before and after the rally ultimately showed that by September 2, nearly a month from when the rally began, cases increased both in Meade County and in counties that contributed the highest inflows of rally attendants, compared to ones that did not.

"Synthetic control models" is academic-speak for "we guessed". In other words, the "study" did not document a single actual case of CCPVirus infection occurring at Sturgis, merely argued that because people's cell phones had been at Sturgis and were then in a location with an uptick in CCPVirus cases, the cases must of have originated at Sturgis.

Does that argument make sense? Not in the slightest.

The Wall Street Journal Editorial Board made short work of ripping the study to shreds, pointing out that, in spite of the study's apocalyptic accusations, South Dakota still has one of the lowest mortality rates in the US.

South Dakota still has among the lowest per capita death rates in the country (19 per 100,000) and fewer deaths and cases per capita than its neighbors Nebraska and North Dakota. Covid patients currently occupy 3% of state hospital beds and 6% of intensive-care units. So it seems that attendees at least didn’t expose the society’s vulnerable to the virus even if they were putting themselves at risk.

Sturgis rally attendees did not wind up in the hospital sick with CCPVirus--certainly not in South Dakota.

Moreover, the study's core methodology was to extrapolate from percentage increases in counties with rally attendees to derive a projected total of cases caused by the bike rally:

Where the study jumps off the rails is linking all of the relative increase in virus cases in counties with attendees compared to those without rally participants. The modelers multiplied the percent increase in cases for counties with attendees by their pre-rally cumulative cases to get a total of 263,708 additional cases—266,796 including South Dakota’s increase.

In other words, if people in an area with a recent uptick in CCPVirus cases had residents who were at Sturgis, the whole of that case increase was attributed to rally attendance, without regard for other sources of infection.

Does cherry picking a potential vector for disease transmission make sense? Never in any actual scientific study.

In reality, if people encountered CCPVirus at Sturgis (always a possibility), they did not wind up in the hospital in significant numbers--not in South Dakota nor any other state with residents who went to Sturgis.

The legacy media narrative on Sturgis makes zero sense.

Back To School? Not If You Test Positive

Across the country, colleges and universities are grappling with fresh outbreaks of CCPVirus among the student population, and now must decide whether it is safer to send the students back home or keep them on campus.

Many schools have made similar decisions, including James Madison University, North Carolina State University, Colorado College and the State University of New York in Oneonta. Public-health officials worry that dispatching students to their hometowns, often without testing them before departure, could lead to new outbreaks around the country.

Yet in these four states (James Madison University is in Virginia), the state hospitalization trends for CCPVirus are all declining. In Colorado and New York especially, the decline has been taking place for multiple months.

Even if we do not call into question the test results themselves (test accuracy is always a question but falls outside the scope of this particular analysis), we still must address the fact that these positive test cases do not appear to require hospitalization.

Are these "asymptomatic" patients? Are they simply getting mild cases of the disease that require little more than bed rest and fluids, much the way ordinary influenza like illness is managed?

If these students who test positive are not sick or not all that sick, and if they are not winding up in hospital, how is it that school officials conclude there is major risk either to keeping them on campus or sending them home?

“Shipping the problem back to the community, where they can further spread, just doesn’t seem like the right answer,” said A. David Paltiel, a professor at the Yale School of Public Health. “Just because a kid is asymptomatic doesn’t mean it’s safe to send that kid home. They could be exposed and incubating. They could be in fact a ticking time bomb.”

How do these students become a "ticking time bomb" if they are not sick?

The dichotomy between school response and underlying data is a recurring phenomenon. At Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois, administrators have sent freshman and sophomore students home literally within days of their arrival on campus. Many are have not even been tested, as the school is responding to an apparent outbreak of CCPVirus in the surrounding Cook County.

According to a report by the Daily Northwestern, Northwestern University has announced that freshmen and sophomore students will be required to leave campus. The decision was prompted by a spike in coronavirus cases in Cook County, Illinois, where the university is located.

Yet, as with the other states, Illinois shows no recent increases in CCPVirus hospitilizations.

How severe is the outbreak, if people are not winding up in hospital?

The hospitalization data does not fit the crisis narrative.

Part Of A National Trend

Nor can we presume that students are merely returning to their home states and taking sick there. According to CDC data, hospitalizations for CCPVirus are down nationwide, and have been trending down for a number of weeks.

People might be testing positive for CCPVirus, but they are not getting sick, and certainly not getting sick enough to require hospital care.

Hospitals Matter

When gauging the severity of a disease, the frequency of hospitalization is an essential metric, for the obvious reason that people who do not require the close medical care found in a hospital are by definition not that sick. People who are not in hospital do not strain the healthcare system. People who are not in hospital are not on ventilators--and presumably are among the least likely to die from disease (one hopes that as a patient's condition deteriorates he or she would go to the hospital before it was too late).

In the United States at least, and in the individual states, people are not going to hospital even if they test positive for CCPVirus. That is not an observable trend.

Does this mean they are not really sick? Does this indicate that perhaps they are not in fact positive for CCPVirus? We cannot make those conclusions from the hospitalization data itself. Such inferences are not valid based just on the hospitalization data.

We can infer that, regardless of the number of new positive cases either in a school, a community, or a state, the current severity of those cases appears to be not that great. It certainly is less than it has been in the past, when hospitalizations were much greater.

Where actual outbreak severity is less than mere case totals might suggest, it follows that less draconian measures are needed to contain the outbreak. Much as with the fiasco of the lunatic lockdown itself, the reflexive academic response to CCPVirus of sending students back home appears to be an overreaction that will do little to inhibit the virus itself, while greatly damaging students' educations.

School policies on CCPVirus, just as community policies, should be based on the actual empirical data at hand.

With the empirical data at hand, school policies on CCPVirus simply do not make sense. That is a problem, one that will not merely vanish as CCPVirus eventually will.