Why Russia Can't Go To A Gold Standard Any Time Soon

There Is No Escaping The Realities Of The Money Supply.

It has now been more than a month since the Central Bank Of Russia announced its “gold peg”, whereby it was committing to buy gold from Russia’s banks at the fixed rate of 5,000 Rubles/Gram.

In order to balance supply and demand in the domestic precious metals market, the Bank of Russia will buy gold from credit institutions at a fixed price from March 28, 2022. The price from March 28 to June 30, 2022 inclusive will be 5,000 rubles per 1 gram. The established price level makes it possible to ensure a stable supply of gold and the smooth functioning of the gold mining industry in the current year. After the specified period, the purchase price of gold can be adjusted taking into account the emerging balance of supply and demand in the domestic market.

With continued interest, according to Google Trends, on Russia’s gold-related maneuvers with the ruble, it is worth investigating the latest events on the ruble front.

On April 26, roughly a month after its initial “gold peg” announcement, the Russian government stated it was planning to back the ruble with a mixture of gold and other commodities going forward.

Russian experts are working on a project to create a two-loop monetary and financial system in the country, Secretary of the Security Council Nikolay Patrushev said on Tuesday, in an interview with Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

He explained that the project involves the provision of the Russian currency with both gold and a range of goods representing a currency value. As a result, the ruble exchange rate would correspond to its real purchasing power parity, he said.

Without getting into the reliability of economic pronouncements made by a nation’s security apparatus, the reality of the ruble is that it is a long way away from being put on a “sound money” basis. A quick survey of Russia’s money supply shows the problem: Russia does not have enough gold—and is likely losing ground on the amount of gold reserves it needs to back the ruble.

Money Supply Basics

To understand the challenge of backing the ruble with gold, it is helpful to understand the basic metrics used to measure a nation’s money supply.

The most conservative metric, the M0 (also known as the Monetary Base), is the amount of actual hard currency either in circulation or held in central bank reserves.

The monetary base (or M0) is the total amount of a currency that is either in general circulation in the hands of the public or in the form of commercial bank deposits held in the central bank's reserves. This measure of the money supply is not often cited since it excludes other forms of non-currency money that are prevalent in a modern economy.

A more widely used metric is the more liberal M1, which adds to the M0 demand deposits (bank checking and savings accounts) and other instruments readily interchangeable with currency (e.g., traveler’s checks).

M1 money is a country’s basic monM2 is a calculation of the money supply that includes all elements of M1 as well as "near money." M1 includes cash and checking deposits, while near money refers to savings deposits, money market securities, and other time deposits (in amounts less than $100,000). These assets are less liquid than M1 and not as suitable as exchange mediums, but they can be quickly converted into cash or checking deposits.ey supply that's used as a medium of exchange. M1 includes demand deposits and checking accounts, which are the most commonly used exchange mediums through the use of debit cards and ATMs. Of all the components of the money supply, M1 is defined the most narrowly. M1 does not include financial assets, such as bonds. M1 money is the money supply metric most frequently utilized by economists to reference how much money is in circulation in a country.

The broadest metric commonly used is the M2, which adds “near money” financial assets which, while not interchangeable with currency, are highly liquid and readily convertible into currency.

M2 is a calculation of the money supply that includes all elements of M1 as well as "near money." M1 includes cash and checking deposits, while near money refers to savings deposits, money market securities, and other time deposits (in amounts less than $100,000). These assets are less liquid than M1 and not as suitable as exchange mediums, but they can be quickly converted into cash or checking deposits.

One way of looking at the M2 is to recognize it as the amount of currency that would be needed if the entire stock of “near money” assets captured by the M2 were to be converted into currency.

It is this M2 measure that shows the ruble’s current unsuitability for backing by Russia’s gold reserves, and comparison to the ruble’s M0 and M1 measures shows the challenge to be getting larger and not smaller.

The Ruble’s Money Supply Metrics

During the month of March, the ruble’s M0, the quantity of physical rubles in circulation, actually declined, from 13913.40 billion rubles to 13834.30 billion rubles.

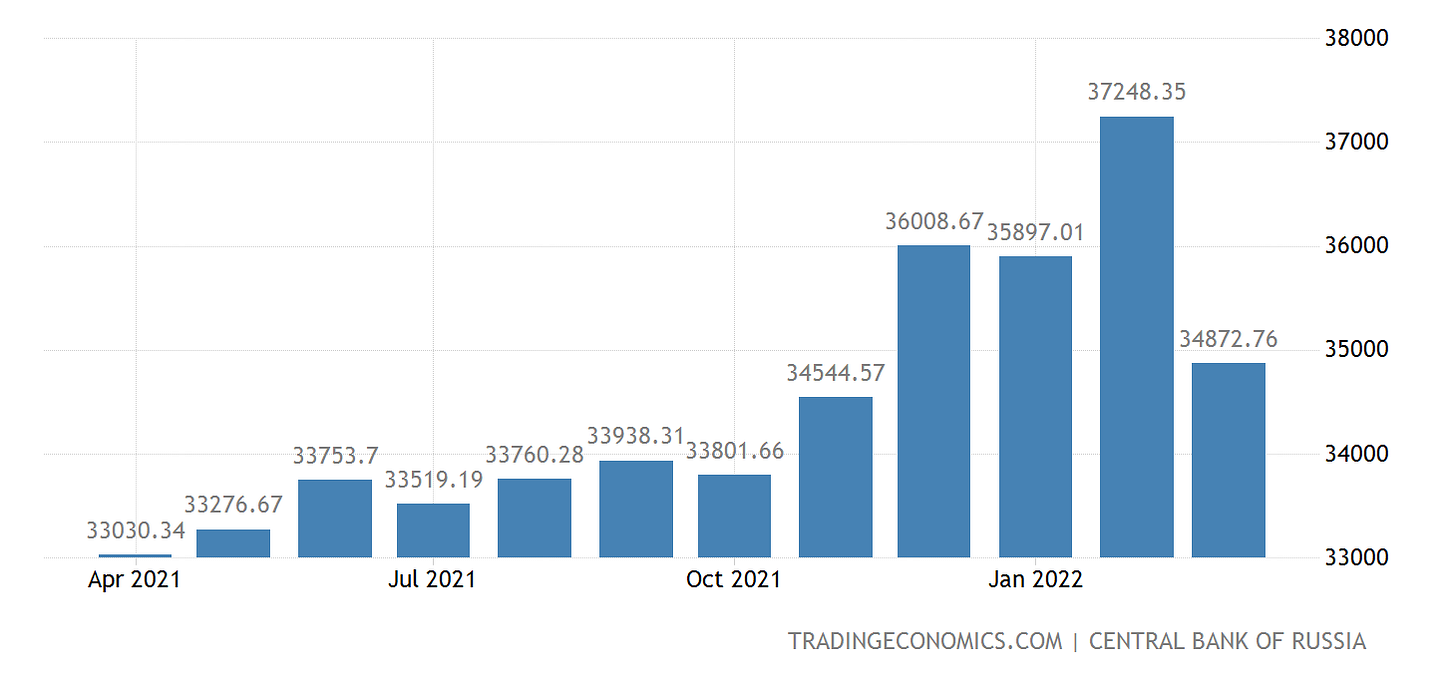

The ruble’s M1 metric had an even more pronounced decline, from 37248.35 billion rubles to 34872.76 billion rubles.

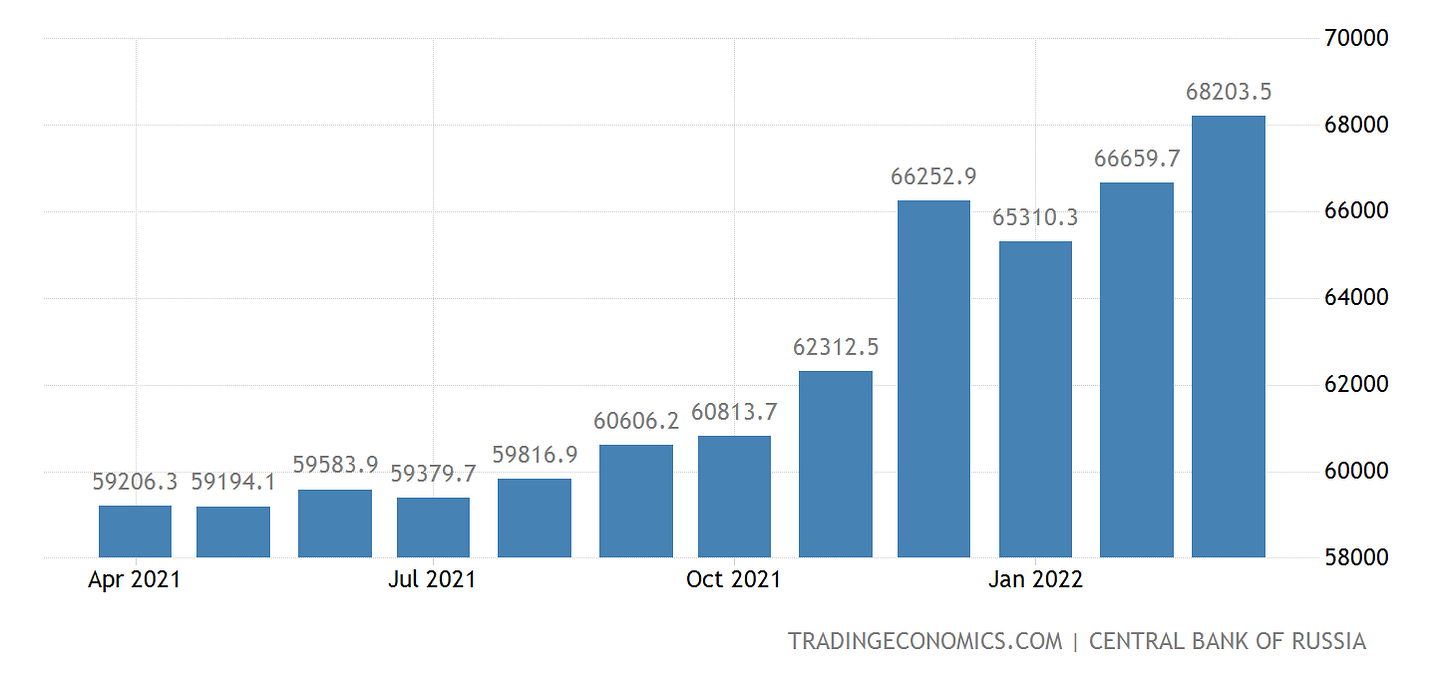

However, the ruble’s M2 metric shows an expansion rather than a decline, from 66659.70 billion rubles to 68203.50 billion rubles.

At a time when the foundations of the ruble are shrinking, Russian banks are expanding the amount of liquid financial assets reliant on the ruble monetary base. From the perspective of backing the ruble with gold, to put the ruble on a gold footing with this dynamic in place risks recreating the currency dynamics that led Nixon to end the gold standard for the dollar in 1971.

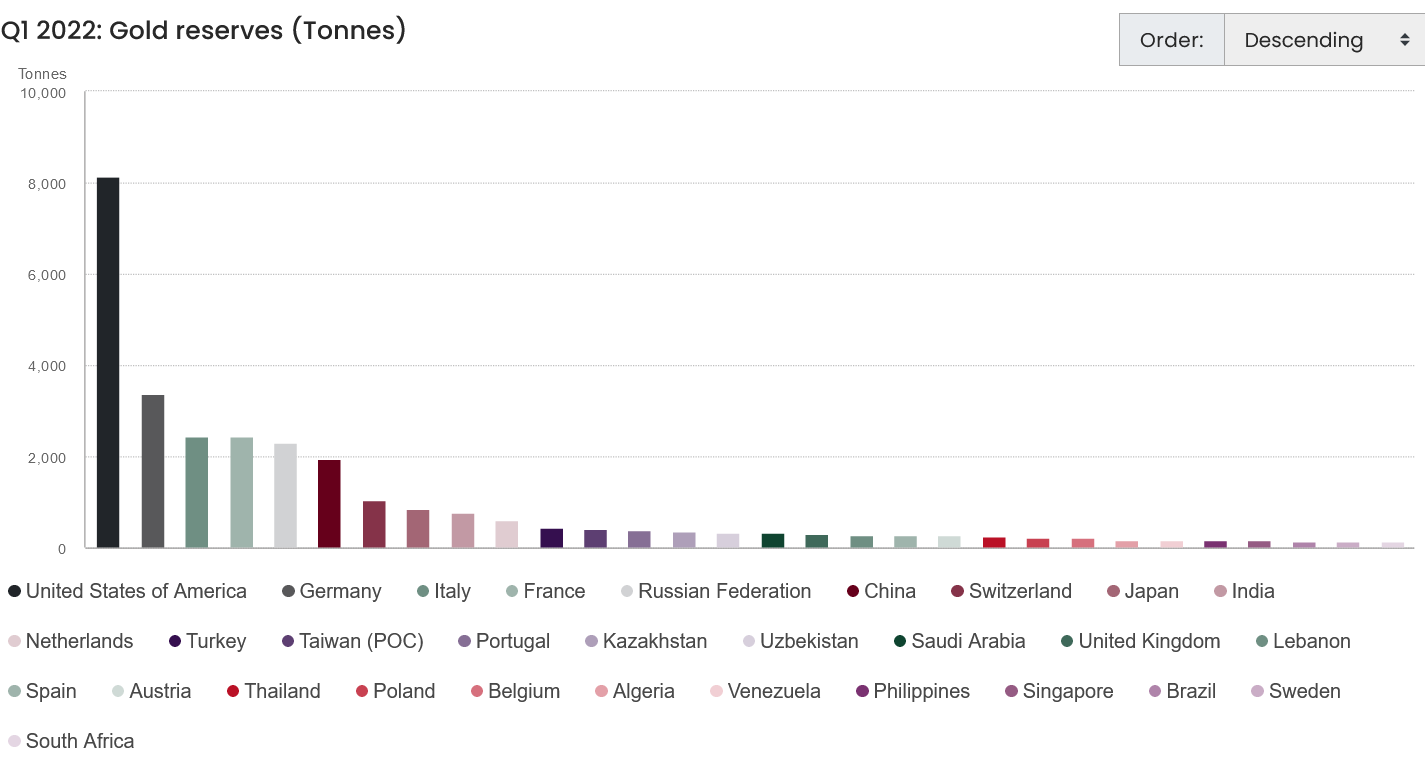

In part this is because, going by the announced CBoR gold peg, Russia’s gold reserves are not nearly enough to back the even the M0 physical currency, despite having the fifth largest gold reserves in the world.

Although the Central Bank of Russia increased its gold reserves in the first quarter, the shortfalls I detailed in my previous exploration of this topic are still very much in place. Russia simply does not have enough gold reserves to credibly back the ruble.

One problem Russia is likely to have in sustaining the gold peg is that it does not have enough gold—an ironic problem since the CBoR is currently buying and not selling gold.

However, if the gold peg is to be a true linkage between the ruble and gold, following Ronan Manly’s analysis, the price must be bi-directional, and the CBoR must be willing to sell gold at the fixed price. Indeed, the proper understanding of a gold standard for any currency is that the currency is redeemable in gold at the set standard rate.

If the CBoR is unwilling to redeem rubles at the stated rate of 5000 rubles per gram of gold, then there is no actual linkage between the ruble and gold, and it is only a matter of time before arbitrage forces within the marketplace force the CBoR to abandon the gold peg. It is in this hypothetical gold-selling scenario that the lack of sufficient gold reserves comes into play.

Where The Gold Fans Get It Wrong

Several precious metals analysts such as BullionStar’s Ronan Manly have rather swooned over Russia’s words and deeds in furtherance of a gold-backed ruble. However, Ronan’s analysis is not only factually flawed, but it ignores the growth of the M2 money supply in Russia.

Ronan’s factual problem lies in his view of the CBoR gold peg as a “floor” price for gold.

In late March when the Bank of Russia offered to buy gold from Russian banks at a fixed price of 5000 rubles per gram, this was the first step in linking the ruble to gold. That move also put a floor price under the ruble and acted as a catalyst for the ruble to re-strengthen ground against the US dollar that had been lost in late February / early March.

The markets have all but ignored Ronan’s “floor price”, as the mid-market price for gold in rubles went below the floor last week and has remained there.

Clearly, the CBoR gold peg is not a “floor price”.

The movement of the exchange rate between gold and rubles merely compounds the existing obstacles facing a transition of the ruble to “sound money”. A declining exchange rate means fewer rubles are needed to purchase a troy ounce of gold—which is the exact opposite of what the CBoR needs to see if it is to use its gold reserves to back the ruble. To move to a gold-backed ruble the CBoR needs to be able to exchange rubles for gold—to sell gold—and right now the amount of gold reserves Russia needs is growing as the ruble price for gold falls.

The Central Bank Of Russia Is Making The Problem Worse

The principal reason for the drop in the ruble’s M0 and M1 money supply is the interest rate measures the CBoR enacted immediately following the institution of sanctions by the west against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine.

The Central Bank had cut the interest rate to 17% earlier this month. The reduction followed an emergency hike to 20% in late February, four days after the start of the military operation in Ukraine. The key interest rate stood at 10% before the launch of the military operation.

Interest rate rises tend to decrease the money supply, and interest rate decreases tend to increase the money supply. Thus, the CBoR’s rate hike to 20% in late February is the likely proximate cause for the ruble M1 money supply to shrink as it did.

However, the 20% interest rate level has not held, and the Central Bank of Russia is now lowering interest rates to 14%, after having reduced them from 20% to 17% just a few weeks ago.

The Central Bank of Russia lowered the key rate to 14% from 17% as it looks to mitigate the impact of international economic sanctions introduced against the nation over the military operation in Ukraine.

The ruble’s rebound from sharp losses in the days immediately following February 24 had slowed the surge in consumer prices during the subsequent weeks, the regulator said in a statement announcing the reduction.

This reduction in interest rates comes even as inflation in Russia continues to rise, having reached 17.6% as of April 22, and is forecast to rise even higher by year’s end.

Russian inflation reached 17.6% as of April 22 and the central bank said on Friday that it expects annual inflation of between 18% and 23% this year, before slowing to between 5% and 7% in 2023 and returning to its 4% target in 2024

Thus, at a time when falling gold prices are reducing the extent to which the CBoR’s gold reserves can back the existing ruble money supply, the CBoR, by reducing interest rates, is allowing that money supply to likely expand still further—the M2 is almost certain to continue its expansion, while the M1 may see a reversal of the March decline.

Despite what other Russian government organs may state, the CBoR’s deliberate policy choice is to move the ruble ever farther away from a “sound money” basis.

Narrative Is Theory, Data Is Reality

The cautionary lesson to be had from the Central Bank of Russia’s policy choices vis-a-vis the ruble is to remember once again that any media narrative, whether in the mainstream media or the alternative media, is often not much more than theoretical wishful thinking. The facts and the data are what tell not only what is, but what is possible and plausible going forward. This is as true in economics as it is in medicine, or in any other scientific discipline.

Financial media analysts and commentators who sing the virtues of sound money are not wrong to do so—for the individual consumer a currency with stable purchasing power will always be preferable. Yet with a central bank managed currency, the inherent reluctance of a central bank to maintain that stable purchasing power must be understood to predominate. Certainly the CBoR is putting its ability to tinker and futz with the ruble money supply ahead of currency stability.

The Putin regime can talk about a gold-backed ruble all it wants. Until the Central Bank of Russia is willing to take the steps necessary to stabilize the purchasing power of the ruble, such talk will never be anything more than empty words.

Lowered the interest rate to 17%. Before the war the interest rate was 10%. That’s crazy. I cannot imagine a 17% (or even 10%) interest rate in the US right now.