And Then Reality (Almost) Set In....

Corporate Media Starting To Realize That The BLS Jobs Report Is BS

When the January Employment Situation Summary came out last week, Wall Street analysts were gobsmacked at how strong the jobs print was for January. They willingly overlooked the extraordinary seasonal adjustments necessary to produce that strong jobs narrative, and were willing to trumpet the “strength” of the US economy on the basis of the BLS’ latest master class in Lou Costello Labor Math.

As Wall Street analysts got over their initial giddiness and began attempting actual sober analysis of the numbers, more than a few have begun to realize the BLS jobs data for January is fictional at best, fraudulent at worst.

Economists at Morgan Stanley point out that the January number reflects three factors it believes to be temporary: unusually warm weather, the resolution of California higher-education strikes and a very strong seasonal adjustment boost. “Seasonal effects are a zero-sum game over the year, so it is likely that the boost in January will be paid for by weaker prints through the first half of the year,” they said in a note published late on Tuesday.

Slowly, very slowly, reality is starting to set in on Wall Street regarding the state of the economy.

It is worth taking a moment to comment on the nature of sound economic analysis—and in turn to highlight why so much of the economic commentary in the corporate media is abysmal and absurd.

We must always be mindful that most economic statistics are derived from surveys and samples, with inferences made to extrapolate from the sample set to the overall economy. This is true of GDP numbers, it is true of jobs numbers, it is true of consumer price inflation.

Accordingly, no single statistic is ever a complete depiction of the economy. Very often you will see me reference a diversity of economic and market metrics, and for precisely this reason—by identifying where diverse metrics intersect and portray the same or similar underlying economic phenomena, we can begin to understand the broad forces at play within the economy.

The failure of the corporate media (and the alternative media and the White House) when it comes to data such as the BLS jobs reports is the tendency to focus on a single metric rather than looking for multiple metrics with which to paint the complete picture. Refreshingly, there are some veteran Wall Street analysts who recognize this shortcoming among their peers.

One of the most basic tenets of statistics is that correlation is not causation. Most things in the macroeconomy are correlated. When people are getting more jobs, it usually means businesses are selling more products. Just because two lines on a chart are moving in a similar direction doesn't mean they explain everything happening in the wide world.

To derive useful concepts from any government report, or any economic data at all, we have to look at how other metrics might align with a mainstay such as the employment level in this country.

One of the first things we should always examine is the overall trend within a metric such as employment level. When we look at the unadjusted jobs data, be it from the Current Population Survey, the Current Employment Survey, or the ADP National Employment Report, is important to see how these statistical measures have changed over time.

This is the first clue that the BLS jobs report for January is hugely overstated. Not only do we see repeated declines in the unadjusted data every January, but there is a decided downward trend throughout 2022 within all three jobs metrics.

At any level of job creation, a downward trend is indicative of a worsening employment situation, not an improving one, and the trend throughout 2022 was that employment was getting worse and not better.

If we index the employment metrics to January of 2022, we see a similar picture arise, especially in the latter half of 2022.

Within the unadjusted data, the Household Survey shows January 2023 to have the same percentage of growth relative to January 2022 as June of 2022—the employment level is 102% of January 2022 both times. The Establishment Survey and the National Employment Report both show less growth in January, 2023 than in June 2022. These are not trends conducive to overall employment growth and job creation.

Just within the BLS report itself, therefore, we have data which calls the January headline claim of 517,000 jobs created into question.

But wait! There’s more!

When we review the quarterly Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey for the fourth quarter of 2022, we see lending trends that are distinctly at odds with economic expansion.

For starters we see significant declines in demand for consumer and small business loans.

Demand for mortgage loans has been in decline since the fourth quarter of 2021.

In part, this is undoubtedly due to a general trend of banks tightening credit standards.

Note that all of these trends more or less align with the Federal Reserve’s increases in the Federal Funds rate (the mechanism by which the Fed attempts to push interest rates up or down).

Tighter credit standards and declining loan demand are two trends that are antithetical to notions of economic expansion—which is to say job growth. For the January BLS jobs report to be taken at face value, we have to accept a premise of massive job creation in the face of an overall reduction in business activity and consumer credit, a clear contradiction in terms.

Yet there is still more!

Throughout 2022, delinquency rates for credit cards as well as other types of consumer and small business loans increased.

Only among collateralized loans did we see declining delinquency rates in 2022.

Again, increasingly parlous consumer finances is a trend that is distinctly at odds with job creation (it also is at odds with the other BLS claim of significant wage growth).

Again, we see correlations between the rise in delinquencies and the rise in the Federal Funds rate.

These trends do help to explain why the increases in the Federal Funds rate have not been matched by rises in market-based treasury yields since November of 2022.

Only this last 25bps rate hike has produced any significant upward movement in yields, and even that was delayed by several days, a pattern not seen earlier in the year.

While the Fed can use the Federal Funds rate to make money broadly more expensive (remember, interest rates are fundamentally the “cost” of money itself), its power to effect actual changes in interest rates is constrained by several market forces, not the least of which is actual demand for credit, loans, and financing. The drop off in loan demand and the increase in loan delinquencies offer strong indications that credit markets in the US currently have no appetite for interest rates much above 4.5-4.75%. Pushing the Fed Funds rate higher at this point will most likely push demand for credit down even farther.

Credit is often viewed as a proxy measure of business growth and expansion, necessary forces to sustain any level of job creation (obviously, if businesses are shrinking there is reduced demand for labor, and so you get job destruction rather than creation). With contractionary trends in both consumer and small business credit, large job creation numbers are simply not likely outcomes.

As I have stated previously, the great danger in the largely fictional BLS jobs report is that the Fed will likely use it to push for still more rate hikes—thereby exacerbating the decrease in consumer and business credit demand, and thus making the existing recession that much worse.

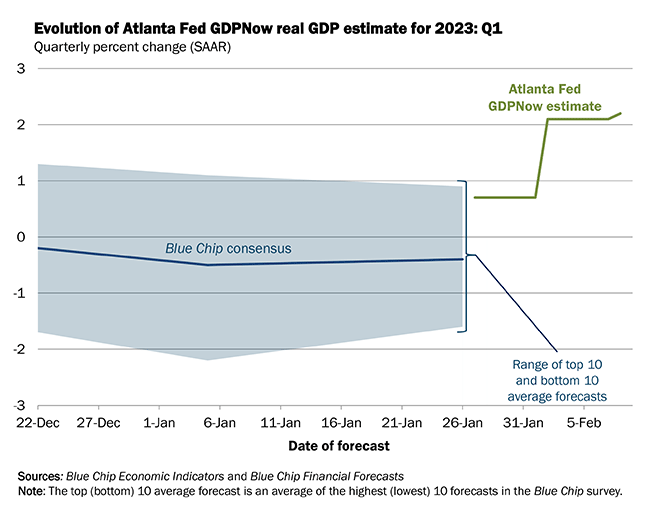

The Atlanta Federal Reserve is telegraphing this exact possibility, with its recent upgrades to its GDPNow nowcast for first quarter 2023 GDP Growth.

The GDPNow model estimate for real GDP growth (seasonally adjusted annual rate) in the first quarter of 2023 is 2.1 percent on February 7, up from 0.7 percent on February 1. After releases from the US Census Bureau, the Institute for Supply Management, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, the nowcasts of first-quarter gross personal consumption expenditures growth, and first-quarter gross private domestic investment growth increased from 1.9 percent and -9.3 percent, respectively, to 3.0 percent and -6.2 percent, respectively.

The Fed has already decided to take the BLS jobs report at face value, despite the myriad of data points indicating that is extremely unwise. With a seeming robust and growing labor market, the Federal Reserve is not only free to raise rates further but, within the rubric of its thesis on how to corral inflation, is almost obligated to raise rates further.

The corporate media has already said this quiet part out loud.

The Fed has made it clear it will keep raising rates to wring excess liquidity from the economy and bring inflation back down to its goal of “around 2%.” By all accounts, inflation is cooling from its 9.1% peak last summer. But the Fed’s favored measure of price increases, known as the PCE index, was up 5% in December from the year before.

The fact that the labor market has been able to tolerate the most aggressive Fed policy in modern history suggests the central bank is safe to keep rates elevated without triggering mass layoffs and unemployment.

Wall Street is coming around to this way of thinking, as evidenced by trades in interest rate options that pay out if the Fed Funds rate goes to 6% or more.

On Tuesday, a trader amassed a large position in options that would make $135 million if the central bank keeps tightening until September. Buying of the same structure continued Wednesday, alongside similar bets expressed in different ways.

Preliminary open-interest data from the Chicago Mercantile Exchange confirmed the $18 million wager placed Tuesday in Secured Overnight Financing Rate options set to expire in September, targeting a 6% benchmark rate. That’s almost a full percentage point more than the 5.1% level for that month currently priced into interest-rate swaps.

This echoes the sentiment being expressed in CME Group’s FedWatch Tool, which assesses near certain probabilities for rate hikes through at least September—which would push the Fed Funds rate to at least 6% if not higher.

On the surface, at least, Wall Street is not attempting to fight the Federal Reserve. Rather Wall Street is doing what Wall Street does: look for ways to profit from government actions and interventions in the economy.

However, even Wall Street cannot make money where demand is choked off and suppressed. The declines in loan demand across the board certainly suggest that the Fed’s rate hikes and corresponding market rises in yields through the summer of 2022 have been sufficient to suppress and largely eliminate credit demand in the US economy, which in turn has stopped yields from rising much in response to the fall and winter rate hikes by the Fed.

There is a very real possibility that further hikes by the Fed to the Federal Funds rate will not push market yields on Treasuries up much if at all. Even without additional increases in yields, however, an elevated Federal Funds rate is likely to be a sufficient market force to continue suppressing loan demand. Regardless of what one thinks of borrowing, without at least some borrowing business expansion, job growth, and economic growth overall are simply not achievable.

Whether Wall Street understands this is debatable. Certainly the Federal Reserve has shown no understanding of this.

Wall Street is embracing (for now) the probable reality of the Fed continuing to hike interest rates throughout most of 2023. It has yet to grasp the reality that the US economy is already in recession, and that any effort by the Fed to push rates further will only push the economy that much farther down recession’s rabbit hole.