Wall Street has worked hard to sustain its “oil demand growing” narrative. At every turn, Wall Street has pushed a price gain as a sign of a new rally, while dismissing every price drop.

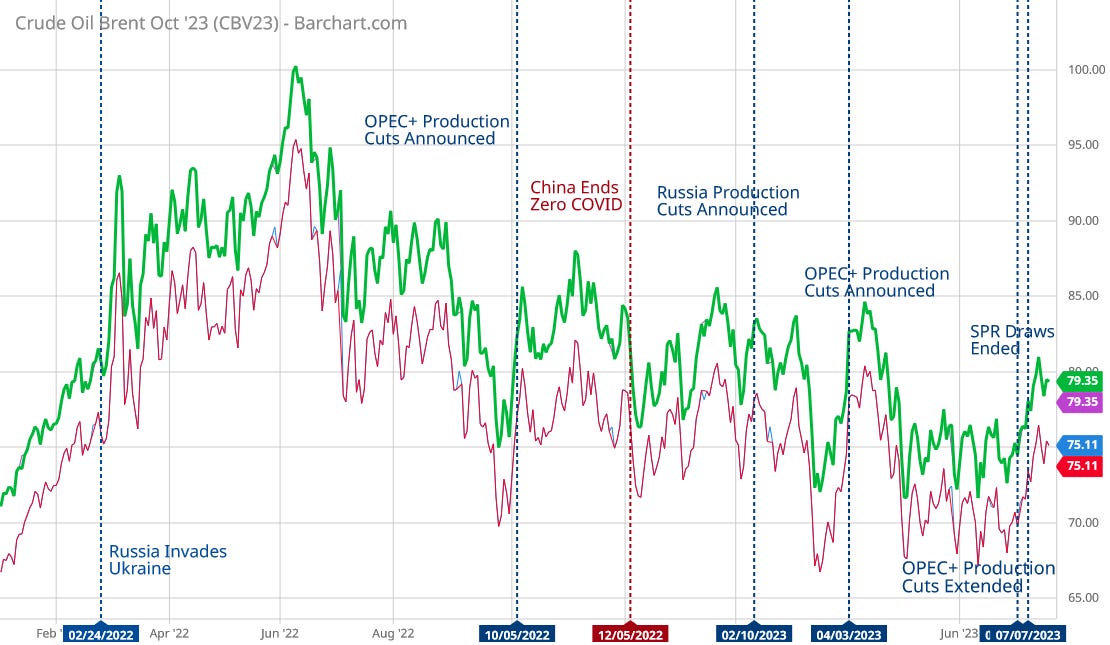

Production cuts were heralded as harbingers of new high prices, ignoring the reality of marginal price increases (if that) after major production cuts.

So much enthusiasm for the narrative….so many dashed hopes, as sagging demand and the ongoing specter of oil price deflation continue to stalk oil markets.

The only thing more volatile than spot oil prices thus far in July has been the media’s up-then-down reporting of them.

It pounced on the price gains at the beginning of the month after Russia and Saudia Arabia extended their production cuts.

That celebratory moment was cut short a few days later, when Saudi oil customers cut back on their oil purchases as prices rose.

Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman attempted to reassure the markets by promising OPEC+ would do “whatever is necessary” to support oil markets.

These salvage efforts appeared to be rewarded by July 11, when Bloomberg crowed about rising oil prices and the oil market “finally starting to flicker into life”.

The kingdom and its partners in the OPEC+ oil producer alliance have been restraining supply for months now, with relatively little impact on the futures market. Brent oil traded in London had been stuck around the $75-a-barrel mark for weeks. That shifted a little Friday, when the contracts rose to about $78, a level they have largely held at since.

Unfortunately, the International Energy Agency did not help when, just two days later, it trimmed its Global Oil Demand Outlook by 220,000 barrels per day.

Global oil demand won’t grow as fast as previously expected this year due to the faltering economies of developed nations, the International Energy Agency said.

World fuel consumption will increase by 2.2 million barrels a day — or about 2% — in 2023, a reduction of about 220,000 barrels from last month’s forecast, the Paris-based agency said in a report on Thursday. Demand nonetheless remains on track to hit record levels later this year, draining inventories substantially in the second half.

Reality continued to set in when oil prices dropped Friday, July 14, and again on Monday, in response to China’s deflating economic data.

The recurring theme of dashed hopes led led Ed Morse, Citibank’s head of commodities research, to tell the oil bulls they were doing it wrong.

Crude futures jumped above $80 a barrel in London last week for the first time in two months, on signs that rising demand and OPEC+ supply cuts are finally causing global markets to tighten.

But it’s just an artificial veneer of tightness, Citigroup Inc. contends, as output curbs by Saudi Arabia and its partners camouflage the absence of a solid demand recovery in China — the world’s biggest oil importer.

“The bulls got it all wrong,” said Ed Morse, the bank’s veteran head of commodities research. “The world is still waiting for a real Chinese recovery, Europe is in recession and we still don’t know if the US will have a hard landing.”

Fundamentals in the crude market have been fragile for some time, Morse says.

That did not stop the markets from staging a mini-rally on July 18, nor the media from growing hopeful once more over the price gains.

Oil prices regained Tuesday all that they lost in the previous session as attention shifted from the gloom over the Chinese economy to the bright and shine that the weekly report on U.S. petroleum inventories would supposedly bring.

Then the US Energy Information Administration appeared to confirm Ed Morse’ assessment of the oil market, when it reported crude draws at only a fraction of what was anticipated.

U.S. crude inventories fell by just a third of expected levels last week despite an end to drawdowns from the national oil reserve, government data showed Wednesday.

Changes to fuel inventories were also underwhelming, the Weekly Petroleum Status Report from the Energy Information Administration, or EIA, showed. Gasoline balances also dropped less than forecast, although distillates saw a smaller-than-expected build that suggested better demand in that aspect.

The U.S. crude inventory balance fell by 0.708M barrels during the week ended July 14, versus the 2.44M-barrel decline forecast by industry analysts tracked by Investing.com. In the prior week to July 7, crude stockpiles surged by 5.946M barrels, the most in a month.

Despite the best efforts of the media to promote a narrative of growing oil demand, it just has not materialized.

However, there is little wonder why the narrative has not taken hold: oil prices simply have not cooperated. Even as oil prices finally broke out of the trading band of the past two months, benchmark Brent crude was only able to reach just about the middle of the previous trading band before retreating again.

West Texas Intermediate, true to form, tracked Brent Crude at a discount of ~$4-$5/bbl.

Yet even this year’s trading bands for oil amount to little more than a more gradual decline in oil prices from last summer’s peak.

OPEC’s own OPEC Basket benchmark has not done any better, with even the extended production cuts only barely pushing the spot price above $80/bbl.

Even Russia’s benchmark Urals Crude has not done particularly well, with about the only pricing victory it has to show is once again shattering the EU/G7 price cap of $60/bbl, closing at $62.570/bbl as of this writing.

The long-term trend for oil prices points in one direction: down.

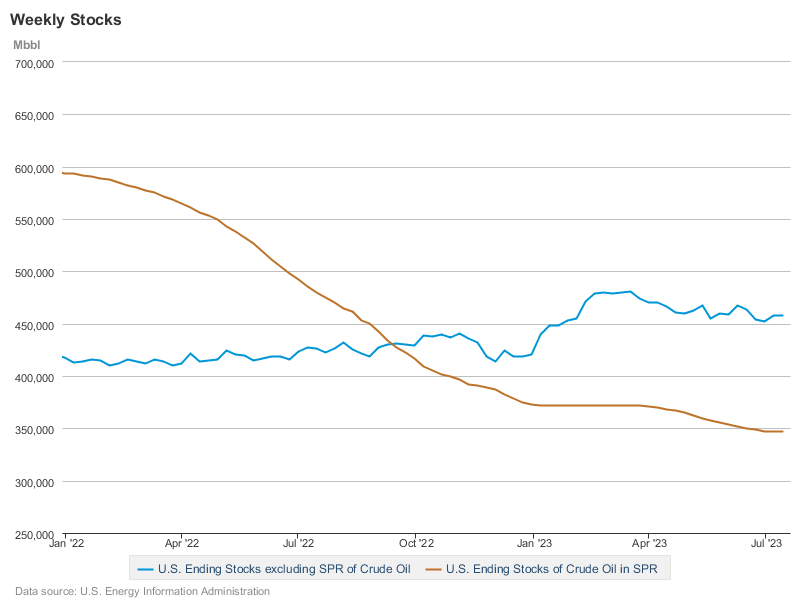

This is not a price trend that reflects growing demand. It especially cannot reflect growing demand when oil stocks are increasing, which they have been in the US.

Oil stocks have been increasing even as draws from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve have tapered off.

Oil stocks represent oil pumped but not sold and delivered. Rising oil stocks mean more oil is getting pumped but not sold. Lack of oil sales is by definition lack of oil demand.

This is not the narrative Wall Street wants to hear.

As readers of this Substack know, however, lack of oil demand is the narrative the totality of the data will support.

Which is why energy producer prices, which dropped precipitously in May, only achieved a marginal recovery in June.

Global demand appears to be the weakest, as energy for export declined last month, even as government purchased energy and finished consumer energy goods increased.

Intermediate demand for oil refined products did increase slightly in June, but demand for unprocessed fuel dropped by a larger percentage.

If oil markets are going to truly “tighten”, these price shifts need to become considerably larger and considerably more positive.

On every dimension, the macro trend for oil is towards a lower price. Lower prices mean supply is continuing to outpace demand, resulting in surplus. Even with production cuts from both OPEC and Russia, amounting to as much as 2 million barrels per day, supply is still outpacing demand.

The very best scenario the prices show for the recent extension of the production cuts, supply is now roughly equal to demand—and the peaking and then decline of oil prices suggests that supply continues to outpace demand.

The Saudis and the Russians keep cutting, and demand keeps falling, always just below the new reduced output level. Eventually supply and demand will even out and establish a market equilibrium. We have seen signs of this in the trading bands for oil that have occurred during the year to date: oil markets establish a dynamic price equilibrium which lasts until some event disrupts the overall balance. Thus far, when that has happened, the new equilibrium is established at a lower price, illustrating yet again

However, the trading bands we have seen this year, both of which were largely established after OPEC production cuts were announced, have seen their upper bound broken only to have the new trading equilibrium established at a lower price than before. That indicate that oil demand is not merely soft but is itself shrinking.

The world is not demanding more and more oil, at the moment, but progressively less less and less. That has been the macro trend since October of last year.

Degrowth is part of the plan to build the 'fourth industrial revolution' per the WEF. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/09/partnering-with-nature-is-the-only-way-to-achieve-true-sustainability-says-tariq-al-olaimy/