Bad News For The Fed: Fake Job Openings Rose In April

Fake Data Means Real Pressure On Fed To Raise Rates

Poor Jay Powell. He just can’t catch a break from the labor market, which keeps churning out data showing job growth, positive hiring trends, and a continued “strong” labor market. Yesterday’s release of the April Job Opening and Labor Turnover Summary report was merely the latest indignity Powell has had to endure.

The number of job openings edged up to 10.1 million on the last business day of April, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the month, the number of hires changed little at 6.1 million. Total separations decreased to 5.7 million. Within separations, quits (3.8 million) changed little, while layoffs and discharges (1.6 million) decreased. This release includes estimates of the number and rate of job openings, hires, and separations for the total nonfarm sector, by industry, and by establishment size class.

The corporate media, true to form, immediately pounced on the still meaningless job openings number to argue yet again how “strong” the US economy is.

Job openings in April rose to their highest level since January. The resilient labor market data adds to a growing narrative that continuously strong economic data could prompt the Federal Reserve to hike interest rates again in June.

The latest Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTs report, released Wednesday revealed 10.1 million job openings at the end of April, an increase from the 9.8 million in job openings reported in March. Economists surveyed by Bloomberg had expected 9.4 million openings in April.

Also true to form, they completely neglected to pick apart the headline numbers and look at the detail underneath. Had they done so, they might have finally seen just how broken the labor reporting systems are at BLS. Then Jay Powell might not have to deal with the real pressure to “do something” based on fake jobs data.

Wall Street reacted to the “bad good news” in predictable fashion—the stock market went down.

Even Dementia Joe’s handlers, in an uncharacteristic display of restraint, refrained from tweeting out his usual nonsense about how well “his” economic programs are working.

Still, Wall Street might have a sense that something is off with the JOLTS data, as the forecast on the Federal Reserve’s next rate hike shifted from favoring a 25bps hike in the federal funds rate to holding the line at the current rate level.

If Wall Street truly believed the JOLTS numbers were legit, the expected response from the Fed would be another rate hike of at least 25bps (the Fed is still hung up on the idea that interest rates and employment levels correlate).

How are the JOLTS numbers “fake”? Simply put, the numbers do not show the labor market strength the corporate media claims they do.

For starters, the reported levels of job openings since the government-ordered recession in 2020 have never been reflected the reported hiring patterns.

Aside from a momentary blip in hiring immediately after the lockdowns ended, both hires and separations have remained within the long-term historical range of between 4 million and 7.5 million individuals each month.

At no point since 2020 have the elevated job openings levels been reflected in significantly greater hiring trends. The elevated job openings have certainly not succeeded in pulling the 5.2 million workers technically not in the labor force who nevertheless want a job now—workers mainly sidelined as a result of the lockdowns—back into the ranks of the employed.

How can a labor market routinely described as “tight” be unable to pull forcibly sidelined workers back into the labor force?

In fact, the JOLTS data only looks the way that it does because it ignores all workers not considered part of the labor force. When the JOLTS report calculates there are 1.8 job openings for every unemployed worker, it is looking only at the number of workers counted as “unemployed”.

However, if one includes the 1.4 million “marginally attached” workers who are not in the labor force but want a job now, that ratio drops to 1.4 openings per unemployed workers. If one includes the 5.2 million workers not in the labor force but who want a job now that ratio becomes 0.9 jobs per unemployed worker.

The exclusion of workers not in the labor force is a routine practice by the BLS, and it routinely distorts the labor picture portrayed by the BLS’ own data, as we can see if we look at the historical ratio of job openings per unemployed worker vs job openings per unemployed workers plus marginally attached workers vs job openings per unemployed workers plus workers not in the labor force but want a job now.

With the variation between the ratio of job openings per unemployed workers and that for job openings per unemployed workers plus those not in the labor force who want a job becoming progressively wider over time, it is clear that the labor statistics are systematically undercounting the idle portion of the workforce by systematically excluding a growing number of idle workers.

Such distortions are why we should apprehend US labor markets not as strong or “tight”, but rather as highly toxic.

The job openings reported in JOLTS must be regarded as “fake” because employers are persistently not doing anything to alter the labor dynamics which have rendered all those job “opportunities” highly unimpressive to workers. Employers say they want to hire people to do X, Y, and Z, but are doing very little to persuade anyone to do X, Y, or Z—at the very least they are not doing enough.

Just how toxic US labor markets have become is readily uncovered just by examining the separations data within the JOLTS report.

While the historical trend has been that the number of voluntary separations increases over time, generally corrected back towards a median by recession, that trend has been amplified tremendously since the COVID recession of 2020.

Even after nearly 18 months’ of decline, the number of quits in April is still more than 300,000 higher than it was in February 2020, just before the government-ordered recession. The “Great Resignation” is still very much an ongoing phenomenon.

If we look at the ratio of quits to layoffs over time, we see that the post-pandemic era has by far the highest such ratio.

While economists and sociologists will debate the reasons for this ad nauseum, what the JOLTS data establishes is that people are choosing other than work. People are deciding they don’t like their jobs, would rather not work at their jobs, and are not impressed by the offers of jobs represented by the unfilled job openings reported in JOLTS.

Failure to appreciate this toxic aspect to US labor markets is a major reason why the Federal Reserve’s rate hike strategy has been spectacularly unsuccessful at pushing down employment and squelching all those illusory job openings.

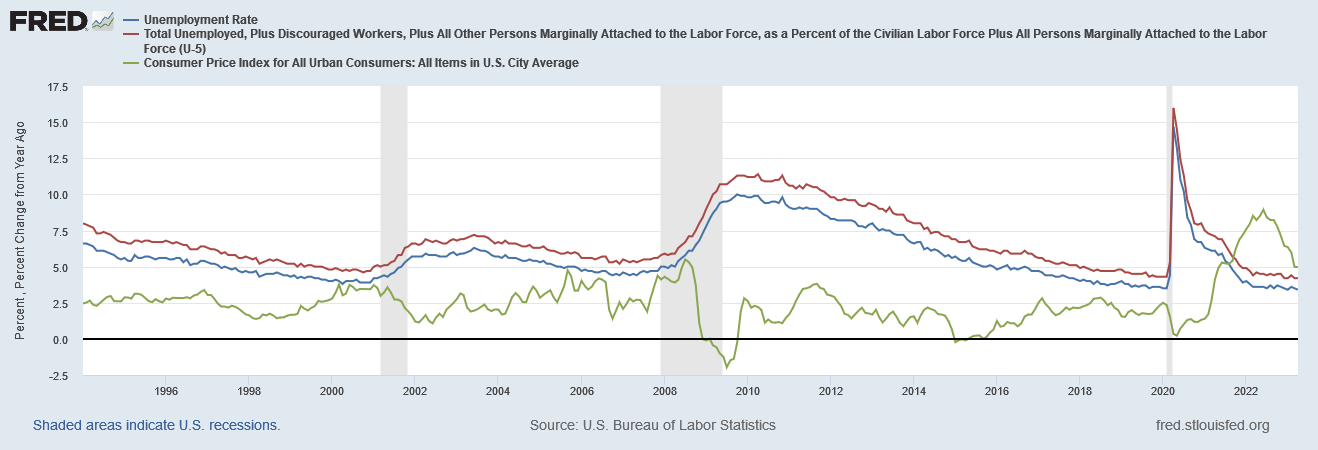

Bear in mind that, even without a toxic labor market, the relationship between interest rates and unemployment is problematic at best. This is immediately obvious when we examine unemployment rates vs benchmark interest rates.

Whether we are looking at baseline unemployment or unemployment plus discouraged and marginally attached workers, the ability of rising interest rates to curtail employment is far from certain. Reducing interest rates may goose employment statistics in the short run, but an benefits they provide attenuate and disappear.

This is confirmed when we look at the fairly weak inverse correlation between interest rates and unemployment.

The covariance between the unemployment rates and interest rates also argues that the two are inversely related, but only weakly connected.

Yet despite this weak and problematic linkage between employment and interest rates, the Federal Reserve has persistently looked to interest rates as a means of “cooling off” labor markets.

Of course, this view of the economy ignores that the relationship between consumer price inflation and employment is every bit as weak and as problematic as that between employment and interest rates.

Calculating the correlation coefficients confirm what is visually apparent on the chart: employment and inflation are not strongly connected.

All of this begs a simple question: How can the Federal Reserve expect rising interest rates to suppress employment when workers are already choosing something other than work? How can rising interest rates dissuade employers from offering people jobs when as it is employers are not making credible offers of jobs?

The answer, of course, is that rising interest rates can do, have done, and will do neither. In hoping that suppressing employment in this country will tame the consumer price inflation beast, Jay Powell is simply grasping at straws.

The headline numbers in the JOLTS report will tell Jay Powell that he must hike interest rates yet again. Alas for Jay Powell, the details within the JOLTS report outline why his efforts will fail miserably yet again.

This is a showdown between the socialists and the capitalists.

Many of the writers on Substack have claimed, and documented, that literally millions of people are out of the workforce because of disabilities caused by the Covid shots. But these, of course, are not discussed, acknowledged, or accounted for in any of the official job-market statistics. So the Fed’s calculations and remedies are going to be off base in any case. Maybe someday, economics students will have an interesting historical case study in scrutinizing this.