With housing markets across the country flashing warning signs of not just contraction but outright collapse, investors in one of the real estate investment trusts (REIT), BREIT, that has fueled market’s rise increasingly want out. And can’t get out.

Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust Inc. has been facing withdrawal requests exceeding its quarterly limit, a major test for the one of the private equity firm’s most ambitious efforts to reach individual investors. The news, in a letter Thursday, sent Blackstone stock falling as much as 10%, the biggest drop since March.

Investors are reading the real estate tea leaves and do not like what they see. Unfortunately for them, BREIT’s structure leaves them no easy way to pull their investment out of the housing market now that the bubble appears to have burst, leaving them trapped as housing markets continue to trend down.

BREIT’’s fundamental challenges reflect those of the overall housing market: rising interest rates and declining home sales.

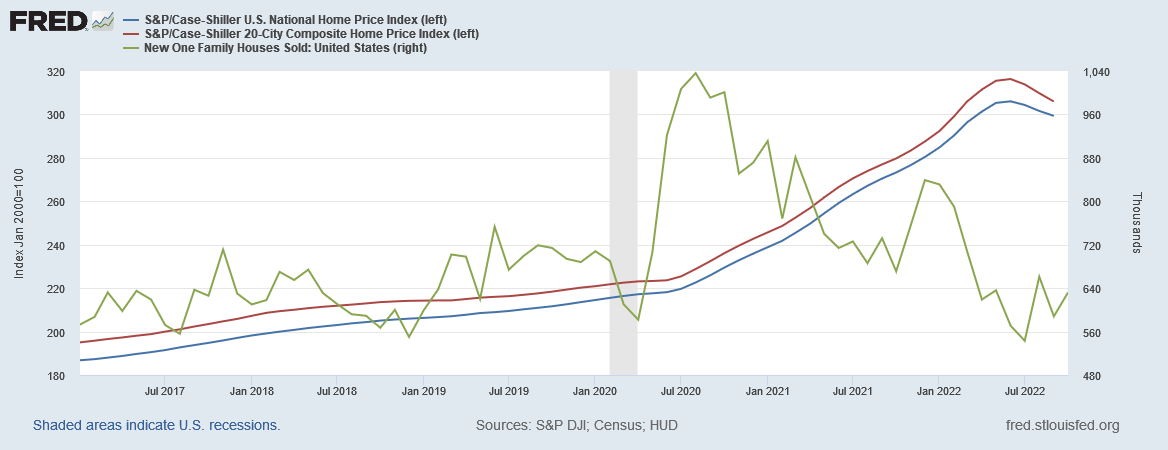

As home prices have risen, the number of home sales has fallen.

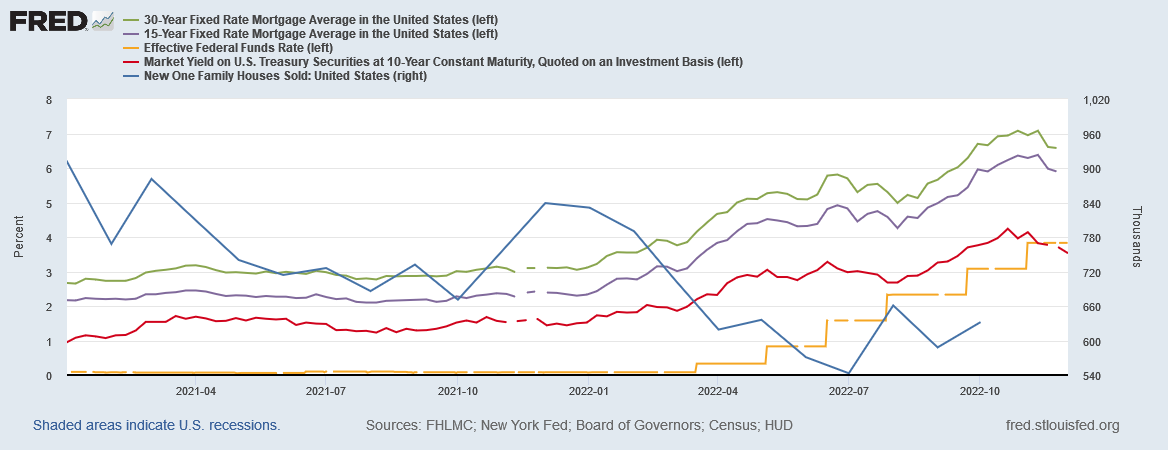

Even more worrisome for BREIT, however, is that as mortgage interest rates have risen, the number of home sales has fallen.

The cooling housing market, with declining house sales, makes it more difficult for BREIT to offload underperforming properties, while also limiting the opportunities for new property acquisitions. Market activity is simply slowing down across the country.

In theory, the lack of market activity and the decline in property values as measured by the Case-Shiller index is not of immediate concern to BREIT, which is heavily concentrated in rental properties and warehousing.

BREIT was built to weather challenging markets, said Nadeem Meghji, head of Blackstone Real Estate Americas, with its portfolio heavily weighted toward rental housing and warehouse assets in the US Sun Belt.

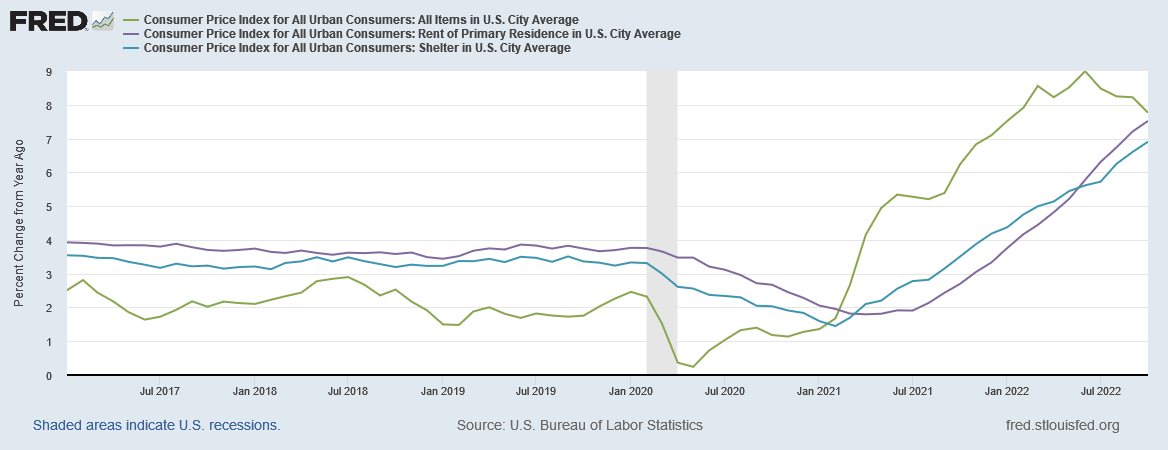

At a time of low apartment vacancies, the fund would appear to be well-positioned to capitalize on rising apartment rents—if apartment rents were rising, that is.

While the shelter price inflation metrics of the Consumer Price Index are still capturing rising rent data, the nature of those subindices is such that they are lagging indicators, slow to recognize price rises and price declines. Thus, they show that shelter price inflation is still rising in the US (at least as a component of the overall CPI).

While apartment vacancy rates are still at historic lows, there has been some uptick in vacancy rates, suggesting there is an upper bound to apartment rent growth.

In fact, there are indications that the upper bound may have been reached. Apartment List’s National Rent Report for November reports a third consecutive month of declining apartment rents nationwide.

Our national index fell by 1 percent over the course of November, marking the third straight month-over-month decline, and the largest single month dip in the history of our index, going back to 2017. The timing of the recent cooldown in the rental market is consistent with the typical seasonal trend, but its magnitude has been notably sharper than what we’ve seen in the past, suggesting that the recent swing to falling rents is reflective of a broader shift in market conditions beyond seasonality alone. Going forward it is likely that rents will continue to dip further in the coming months as we move through the winter slow season for the rental market.

For the whole of 2022, rents are up 4.7% from January to November, an increase in line with pre-pandemic figures, and a significant cooldown from the rental growth of 2021.

The Apartment List data is confirmed by the Zillow Observed Rent Index, which shows rental rates have at the very least plateaued in recent months.

Thus BREIT is facing a cap on the income its existing property portfolio can generate, while facing an increasing challenge in managing the portfolio’s assets in an environment now dominated by rising mortgage and interest rates, after years of abnormally low rates.

In the past decade, the real estate industry reaped the benefits of the Federal Reserve’s policy of low rates. Homebuyers, taking advantage of record-low borrowing costs, went on a spree that fueled double-digit price gains. Ultra-low rates also drove a refinancing boom that put more money in homeowners’ pockets and spurred the creation of jobs for mortgage brokers, title insurance agents and appraisers.

Now, real estate has been among the hardest-hit sectors of the Fed’s campaign to quash inflation by boosting interest rates at the fastest pace in decades.

As an illustration of the pressures rising rates are placing on BREIT, some $21 billion of its $70 billion size is tied up in interest rate swaps bought to manage rising interest rate costs.

The REIT has piled into $21 billion worth of interest-rate swaps this year to hedge against higher debt costs. Such swaps have appreciated by $4.4 billion, helping to buoy the portfolio’s overall value.

The swaps (aka “derivatives”—sound familiar?) have been propping up the portfolio’s value against the general decline in the value of the properties themselves.

The redemptions from BREIT show that investors are not at all happy with this state of affairs. The cooling property markets traps investment vehicles such as BREIT on all sides. A contracting property market presents fewer buying opportunities and also a smaller market in which to offload properties, making it more difficult to shed underperforming assets without taking a loss. At the same time, the plataeu and decline in residential rents indicates a maximum revenue level obtainable from the existing portfolio.

The asset values within BREIT’s portfolio itself are declining, and so are the income potentials from rents of those assets. Investment funds are built on the premise of value increase and rising income streams, both of which are disappearing from BREIT’s housing property niches.

Yet because BREIT is not traded on a public exchange, investors cannot simply offload their shares, but must redeem their investment by directly withdrawing it. As a non-traded REIT, part of how BREIT manages its cash flows is that it has limits on how much investors can pull out in any given quarter, and it has reached those limits.

After years of attracting investors chasing yield at a time of rock-bottom interest rates, BREIT is coming under new pressure. It has thresholds on how much money investors can take out, meaning if too many people head for the exits, it may have to restrict withdrawals or raise its limits.

Investors’ money is, for now, trapped within BREIT even as the value of the assets is diminishing. While this is allowing BREIT to avoid having to make bulk asset sales at fire-sale prices to raise cash for redemptions, investors are not likely to see their investment in BREIT appreciate in value at a time when property values are falling and rental rates have peaked.

While BREIT is just one fund, its $70 billion size gives it considerable heft in the retail investment space, and for much of its existence it has been an attractive investment opportunity for investors seeking out higher yields and returns on their investment. However, rising interest rates are not only increasing the yields from debt instruments and Treasury bills, but are also decreasing the potential yields from other types of assets.

Just as in the runup to the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, a period of rising interest rates is cooling real estate speculation and investment, and investors are starting to feel the pinch. However, as BREIT lured investors in with high yield promises, redemption restrictions means those investors get to ride the same bubble they rode going up at least part of the way going down.

Wealth destruction waits at the bottom.

"Wealth destruction waits at the bottom. "

As does a buying opportunity. :)