BLS Reports More Imaginary Job Openings In January JOLTS Report

Ignores Growing Signs Of Labor Weakness Yet Again

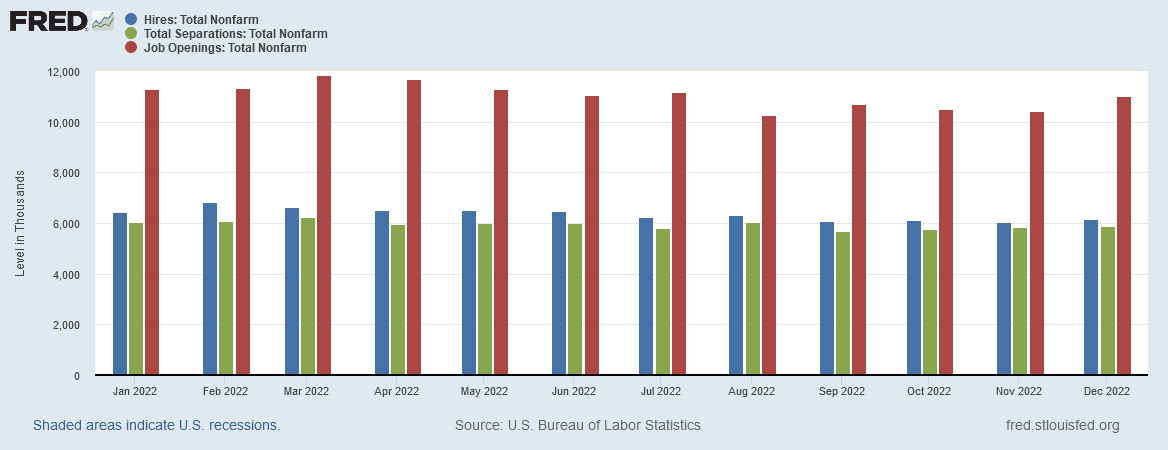

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary, there was a significant uptick in the amount of available job openings in this country during the month of December.

The number of job openings increased to 11.0 million on the last business day of December, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the month, the number of hires and total separations changed little at 6.2 million and 5.9 million, respectively. Within separations, quits (4.1 million) and layoffs and discharges (1.5 million) changed little. This release includes estimates of the number and rate of job openings, hires, and separations for the total nonfarm sector, by industry, and by establishment size class.

More job openings furthers the mythology of a “tight” labor market, which is being dutifully promoted by the corporate media.

U.S. job openings unexpectedly rose in December, showing demand for labor remains strong despite higher interest rates and mounting fears of a recession, which could keep the Federal Reserve on its policy tightening path.

I have my doubts that all of the 11 million job openings being reported in fact exist. The long-term hiring and separation trends in this country suggest most if not all of those jobs are little more than wishful thinking.

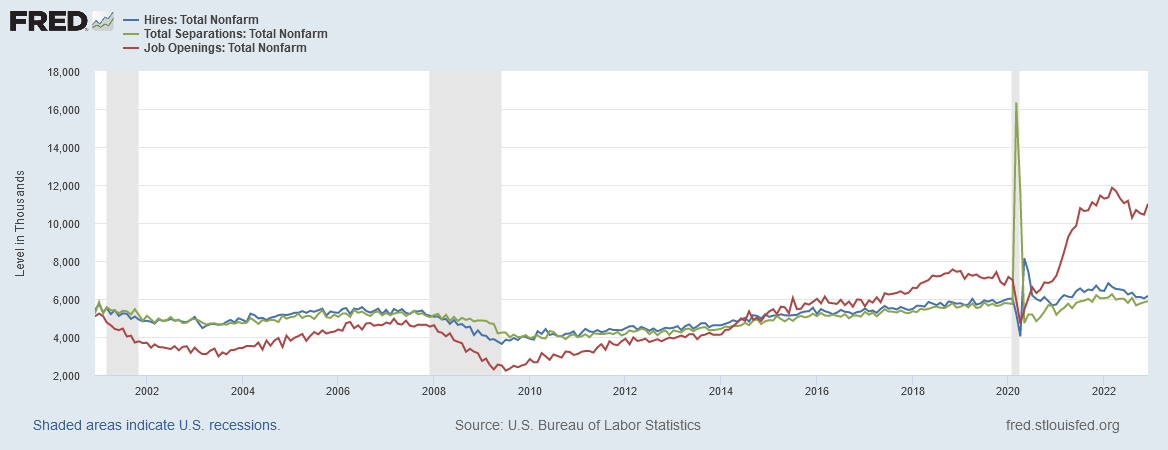

To understand why the reported job openings number is suspect (and has been suspect for quite some time), first look at the hiring, separations, and job openings data over the past two decades.

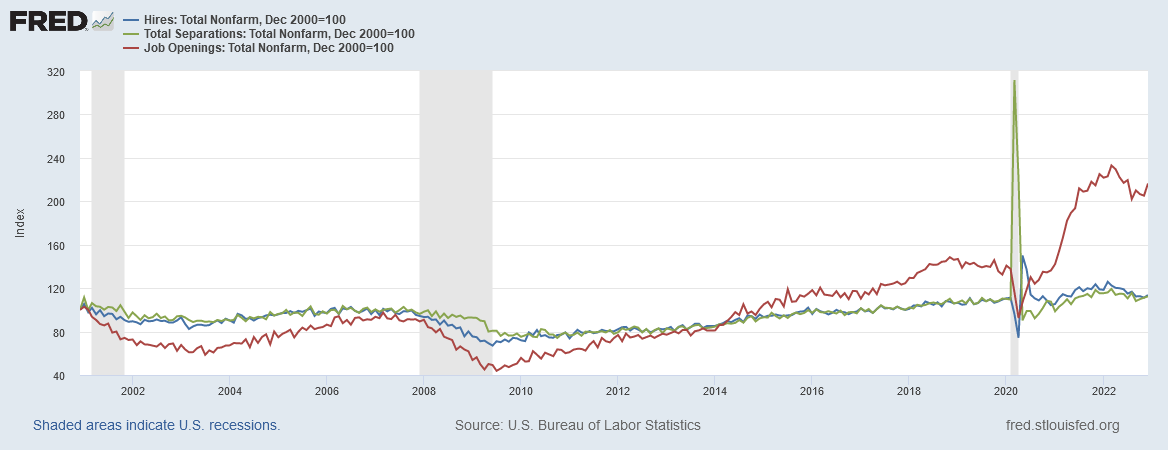

Hiring and separation trends have been fairly constant over that entire period. In fact, if we recast the data into an index, with the baseline date being December, 2000, we find that the rate of hiring in December, 2022, is only 13.6% above where it was in December, 2000, and the rate of separations only 12.4%.

The job openings index, on the other hand, has more than doubled, rising by 116.4%.

Having 1.9 jobs available per unemployed person in this country would put tremendous pressure on wages. With labor that much in demand workers should be enjoying tremendous leverage on wages and labor rates.

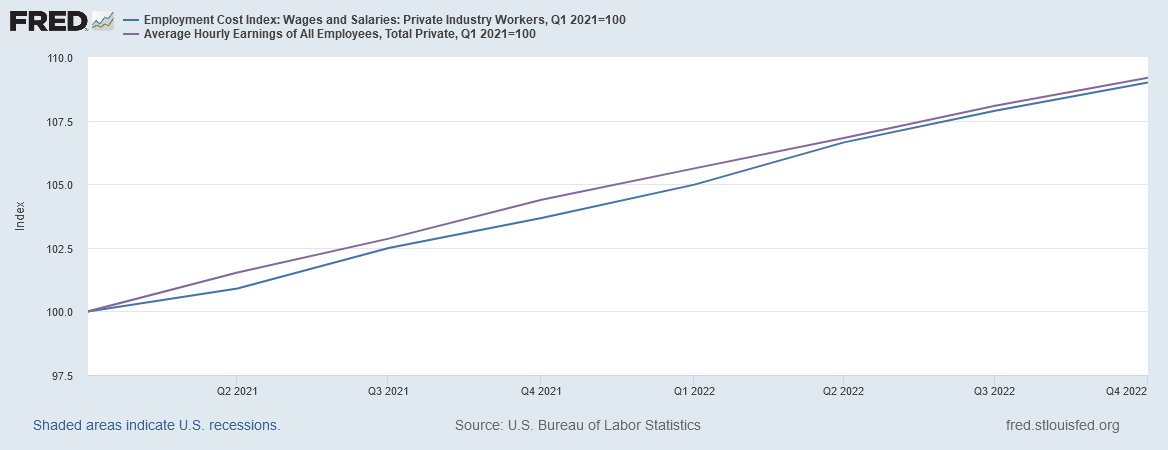

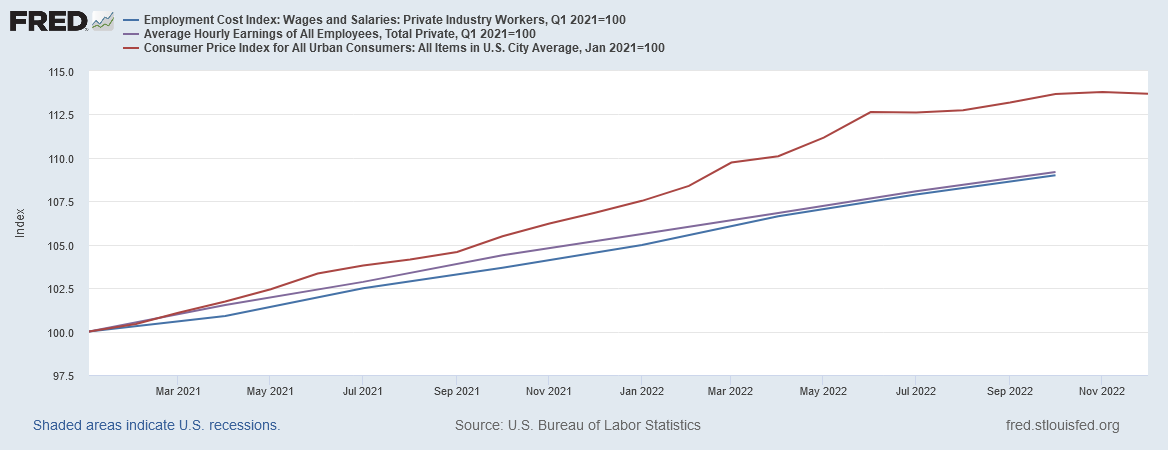

Yet when we look at both reported average earnings and the Employment Cost Index over the past 8 quarters, we do not see any indication that wages are under extraordinary pressure.

Average wages are rising steadily, with no marked change in the pace of wage increase despite job openings doubling.

That suggests that many if not all of the reported 11 million job openings are more in line with wishful thinking than with actual labor demand. If employers were truly desperate to hire more people, we should be seeing an accelerated trend in wage growth, and we do not. What we do see is wages—the cost of labor—rising slower than inflation over the same time frame.

This lack of upward pressure on wages from a scarcity of workers suggests that the actual demand for labor is considerably less than has been represented, which can only mean at least a significant portion of the 11 million job openings simply does not exist.

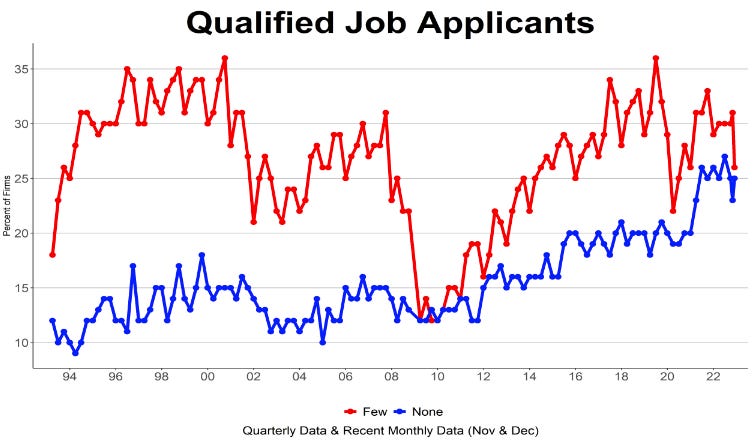

This is not to say that there are no unfilled job openings. The National Federation of Independent Businesses reported in their December jobs report that more than half of federation members have either hired or tried to hire in December, with 26% of members reporting that they could find few qualified job candidates and 25% of members reporting they could find no qualified job candidates.

Overall, 55 percent reported hiring or trying to hire in December, down 4 points from November. Fifty-one percent (93 percent of those hiring or trying to hire) of owners reported few or no qualified applicants for the positions they were trying to fill (down 3 points). Twenty-six percent of owners reported few qualified applicants for their open positions (down 5 points) and 25 percent reported none (up 2 points from November).

Clearly, there are unfilled jobs in the labor markets, although the actual number is probably quite a bit less than reported in the December JOLTS report.

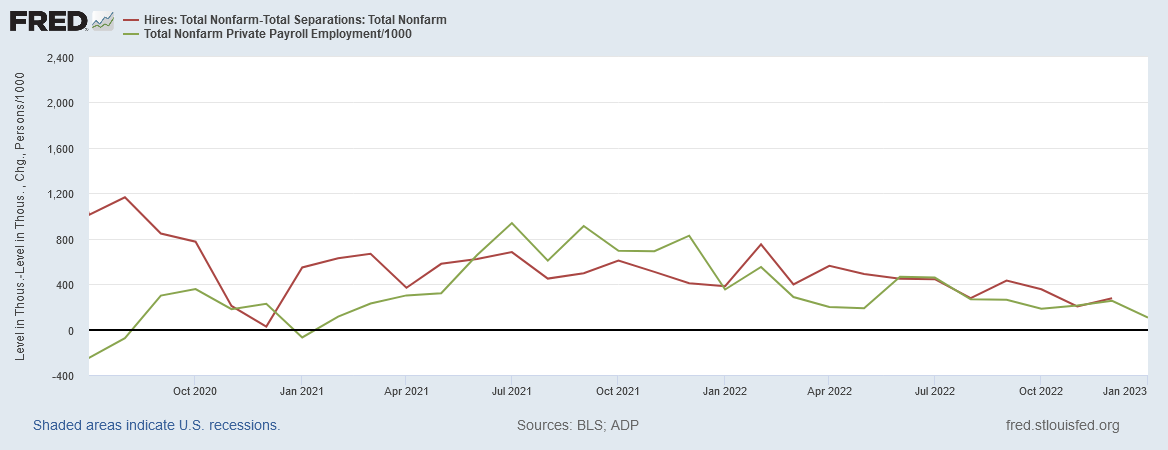

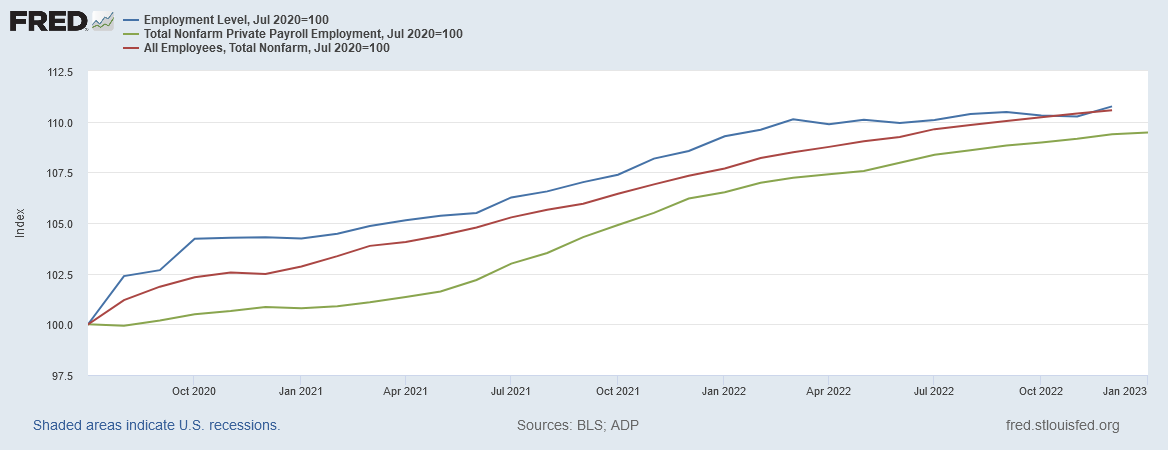

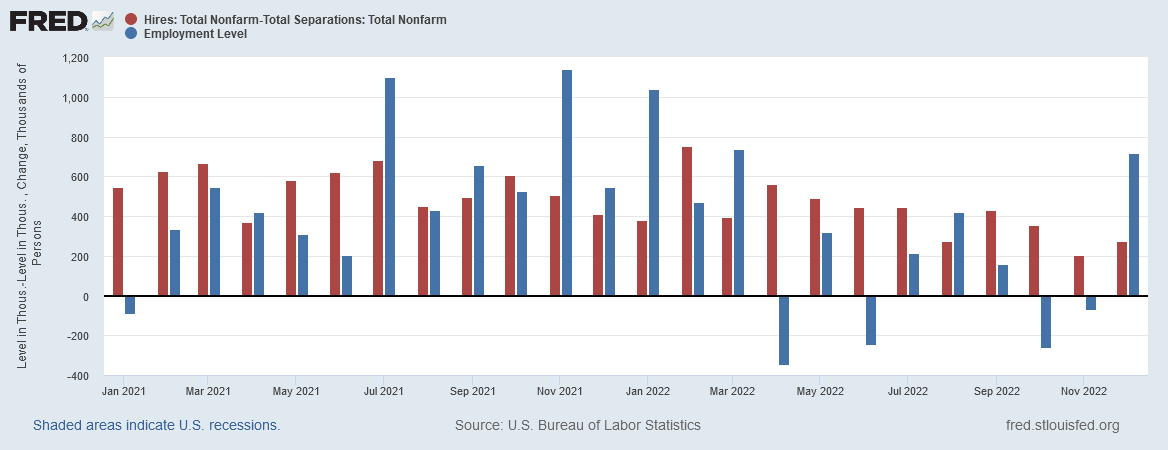

Another indication that the reported level of unfilled job openings is not entirely real is the fact that, overall, net hiring trends per ADP’s National Employment Report have been declining since approximately July of 2021.

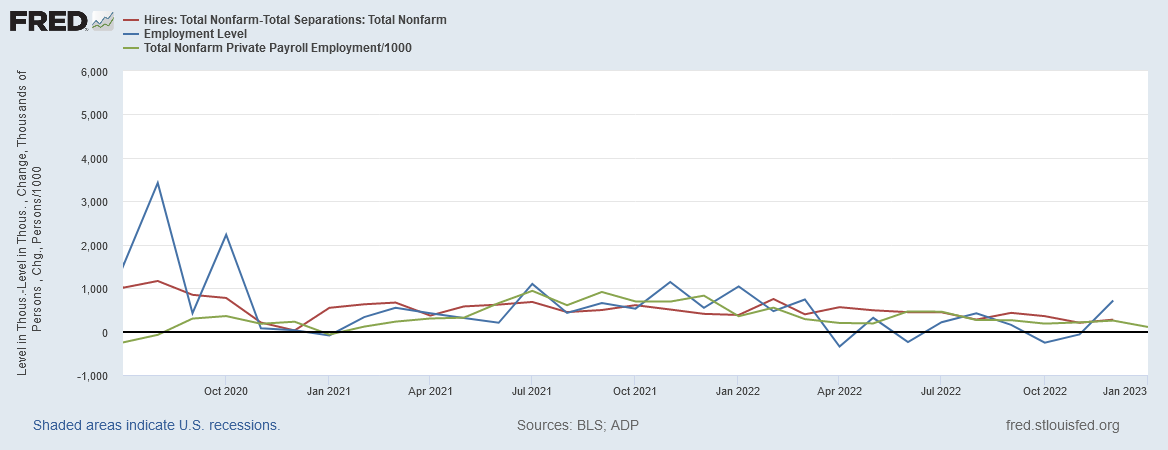

This trend is broadly replicated in the BLS data as well, although the employment level was reported as having increased substantially in December.

Declining employment growth and hiring is difficult to reconcile to large and growing unfilled jobs numbers. Unfilled jobs are the essence of labor demand, and a growing demand for labor presumably would result in a greater utilization of labor—i.e., more hiring and more growth in the employment level.

Keep in mind that, according to the BLS Current Population Survey (Household Survey), the employment level in this country rose by only negligible amounts between March and December, indicating almost no jobs growth from March of 2022.

This plateau in the employment level presents as a greater frequency of month on month employment level decreases since March, 2022, even as net hiring suggests there should be no such decrease.

After going through almost all of 2021 with no decreases in the employment level per the Household Survey, the presence of significant decreases in the employment level after March of 2022 is a rather remarkable shift in the overall employment trend, and speaks to a significant decrease in labor demand, not an increase.

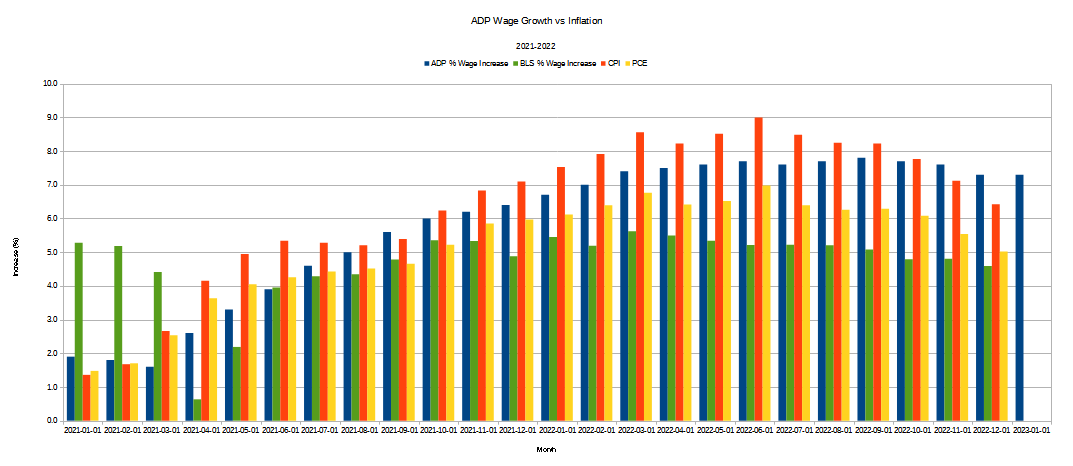

Another indication that labor demand is not as robust as the BLS reports appear to present is the failure of wages overall to keep pace with inflation.

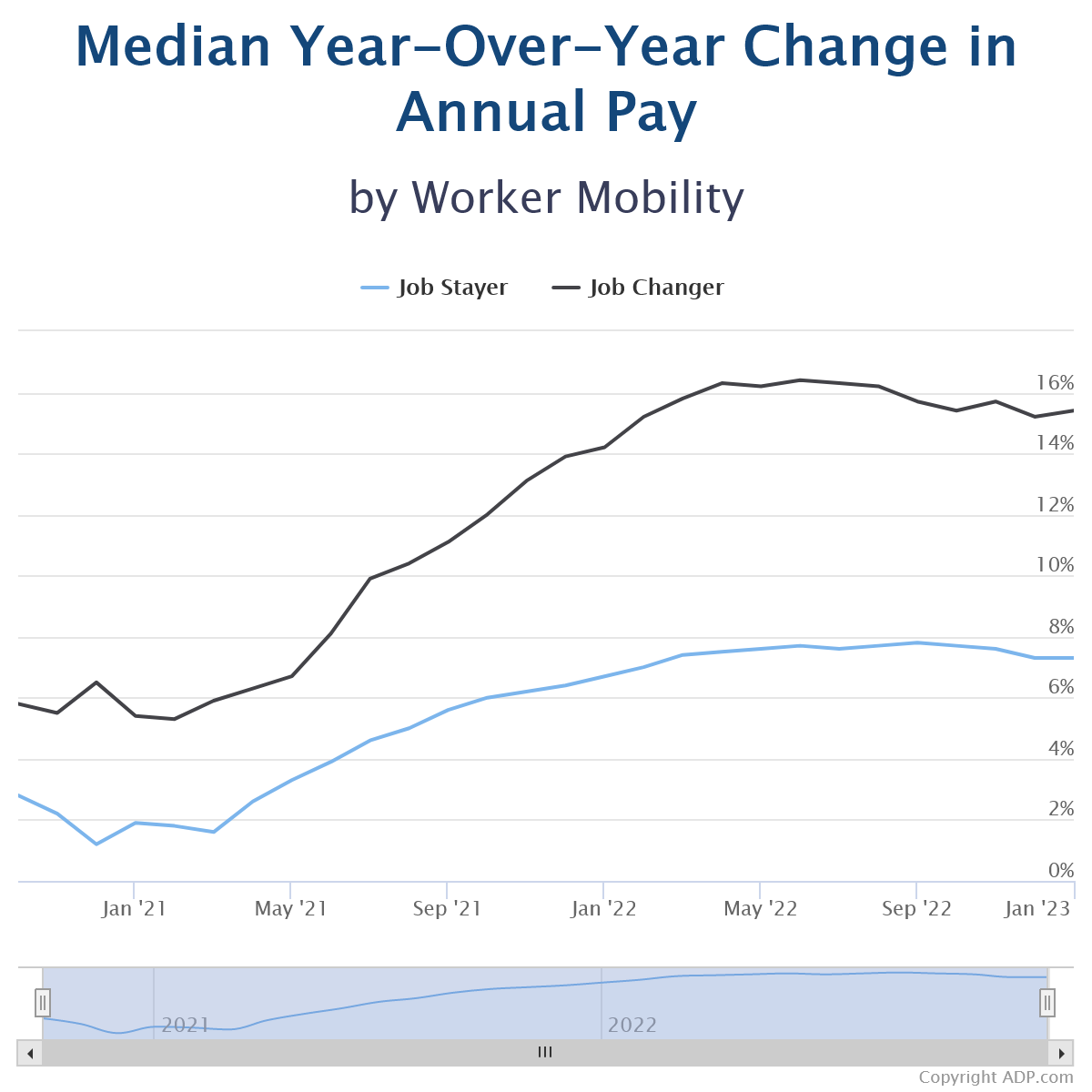

According to ADP’s Pay Insights Report, wages among workers remaining at their job rose 7.3% year on year in January, which was the same percentage as in December.

Among job changers, the average pay increase being reported by ADP is roughly double that at 15.4% year on year.

However, with very few exceptions the monthly percentage rises in wages reported even by ADP has not kept pace with monthly rises in year on year consumer price inflation.

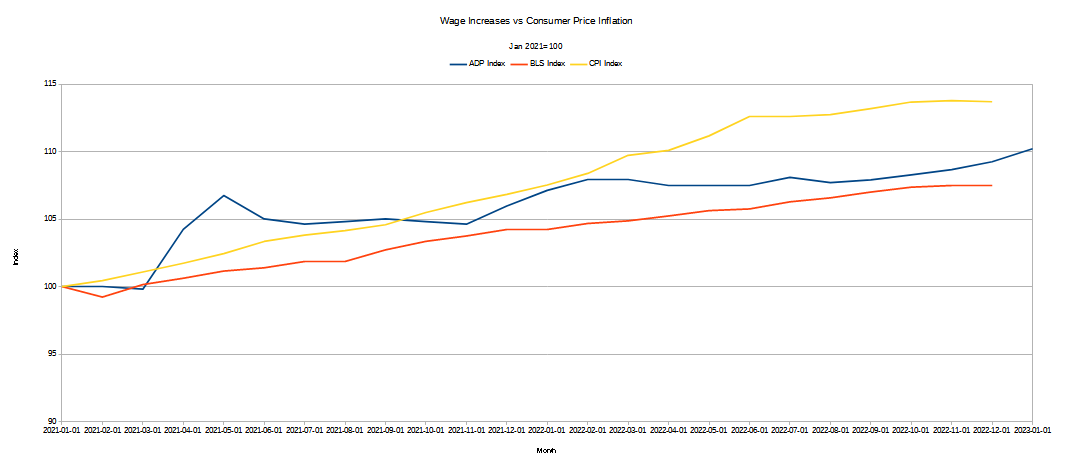

Since January 2021, even the larger wage increases reported by ADP have not kept wages on pace with reported consumer price inflation, although the ADP report shows wages holding up better against inflation than the BLS data.

Even at the ADP reported wage levels, however, wages have only risen 9.2% since January of 2021, while consumer prices have broadly risen 13.7%.

The rising wages reported by the ADP Pay Insights Report again shows some significant labor demand, but not the immense labor demand indicated by 11 million unfilled jobs.

Yet these indicators are not merely showing softer than reported labor demand, but softening labor demand.

When hiring trends head downward, that shows labor demand is decreasing—which is the antithesis of what a truly “tight” labor market produces.

When wages do not keep pace with inflation, and fall steadily behind, that also indicates labor demand is decreasing overall, as increasing demand would result in wage pressures more capable of keeping pace with consumer price inflation (and which theoretically could produce the dreaded “wage-price" spiral1).

As I have stated before, and contrary to what Wall Street analysts believe about labor markets, labor markets are not so much “tight” as they are “toxic”.

The passage of time has not served to detoxify US labor markets at all, and the current jobs data from the December JOLTS report is merely further evidence of this.

If one merely accepts the top level BLS report numbers, such as the reported number of unfilled job openings, it is very easy to paint a picture of economic robustness and rude health. Certainly the BLS is painting that picture, and the corporate media are only too happy to promote that picture.

However, the devil always lies in the details. When one drills into the details behind the top level BLS jobs numbers, one finds that the picture is not one of economic rude health but economic stagnation and weakness, and that the image of unfilled job openings is but an illusion, not a reality.

Banton, C. Wage-Price Spiral: Definition and What It Prohibits and Protects. 31 Mar. 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/w/wage-price-spiral.asp.

The detail is that I have far more friends seeking jobs, than finding them.

Especially in manufacturing.

Some of these folks have moved south and now, even the jobs are drying up.