Timing is, as they say, everything.

Xi Jinping had some pretty horrible timing when he elected to begin easing China’s draconian Zero COVID restrictions just as a fresh wave of COVID cases began moving across the country.

Officially, of course, that is not the case, but with Beijing opting to end mass testing there are no good ways to effectively track cases. However, social media commentary paints a pretty grim picture of a substantial COVID wave impacting most of the country.

Social media users in Beijing and other cities said coworkers or classmates were ill and some businesses closed due to lack of staff. It wasn’t clear from those accounts, many of which couldn’t be independently confirmed, how far above the official figure the total case numbers might be.

“I’m really speechless. Half of the company’s people are out sick, but they still won’t let us all stay home,” said a post signed Tunnel Mouth on the popular Sina Weibo platform. The user gave no name and didn’t respond to questions sent through the account, which said the user was in Beijing.

The official data shows cases are declining, and social media is saying the official data is a load of donkey dung.

Moreover, it’s not merely social media that is portraying China as in the grip of a major COVID infection wave. China observers are gathering other reports that appear to confirm the social media postings.

Despite the official numbers suggesting the caseload had halved, Raymond Yeung, China economist at ANZ bank, said that on-the-ground observations indicated some cities, including Baoding, in the northern province of Hebei, already had “high infection numbers”. More big cities, he said, would soon endure similar levels of infections.

“Like Hong Kong, the actual infection data will no longer be informative. As the ‘official’ infection figures decline, the government can eventually claim their success against the virus,” Yeung said.

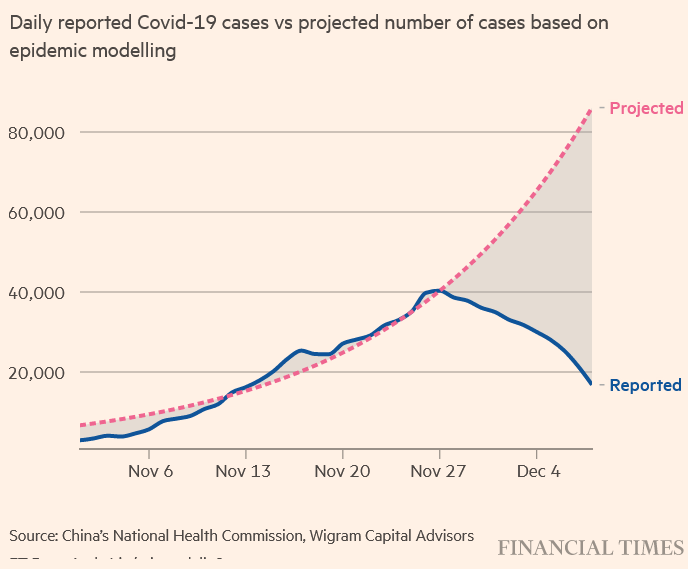

While estimated and projected cases rise, the official numbers show a decline in COVID cases—leaving individual observers to decide which numbers are more credible (hint: not the official numbers).

The situation echoes the dearth of official information during the disastrous initial outbreak in Wuhan nearly three years ago. Local officials and analysts warned that the reduced testing, as well as gaps in reporting of both cases and deaths, would make it harder to assess the risk to the world’s second-biggest economy.

“The behaviour of case numbers is very similar to 2020, where we had one [to] two weeks with genuine case numbers, before the veil was drawn,” said Rodney Jones, principal at Wigram Capital Advisors, an Asia-focused macroeconomic advisory group.

One consequence of the disparity between the “official” and “real” COVID case numbers: many Chinese people are simply not ready to embrace the easing of the Zero COVID restrictions.

Although the government on Wednesday loosened key parts of its strict "zero-COVID" policy that has kept the pandemic largely at bay for the past three years, many people appear wary of being too quick to shake off the shackles.

In the central city of Wuhan, where the pandemic erupted in late 2019, there were more signs of life with some areas busy with commuters on Friday. But residents say a return to normal is a long way off.

"They've relaxed the measures but still there's nobody about," said a taxi driver surnamed Wang, who didn't want to give his full name.

"You see these roads, these streets ... they ought to be, busy, full of people. But there's no one. It's dead out here."

Both the likely rise in COVID cases and the widespread reluctance to shake off the Zero COVID restrictions are not helping China’s economy get going again. While the collapse of China’s real estate sector and the knock-on effects of a contracting global economy have also weighed heavily on the Chinese economy, the impacts of Zero COVID have been no small contributor to China’s economic woes.

This year's depressed growth, while due partly to a domestic property market slump and the global economic slowdown, has also been blamed widely on China's harsh COVID-related restrictions.

Lockdowns and quarantines have disrupted supply chains and depressed consumer spending, and eventually triggered widespread protests that spurred the recent policy shift.

With the Chinese economy already in a parlous state, the reluctance of ordinary Chinese to resume normal commuting and work patterns, coupled with the inevitable absenteeism from work as COVID cases spread, is hardly likely to reenergize the economy—which needs some serious re-energizing.

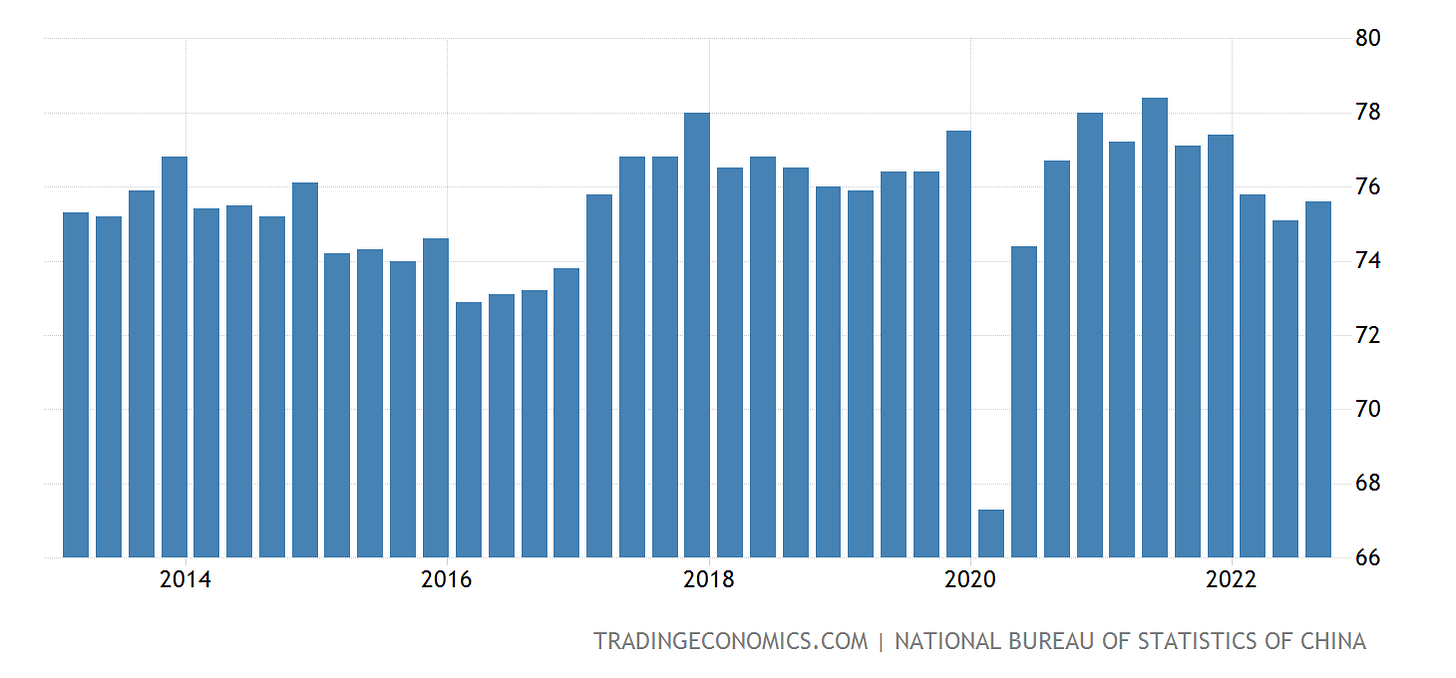

This assumes, of course, that an individual is currently working. China’s unemployment rate has been trending up the past few months, and has been consistently higher post-2020 than before.

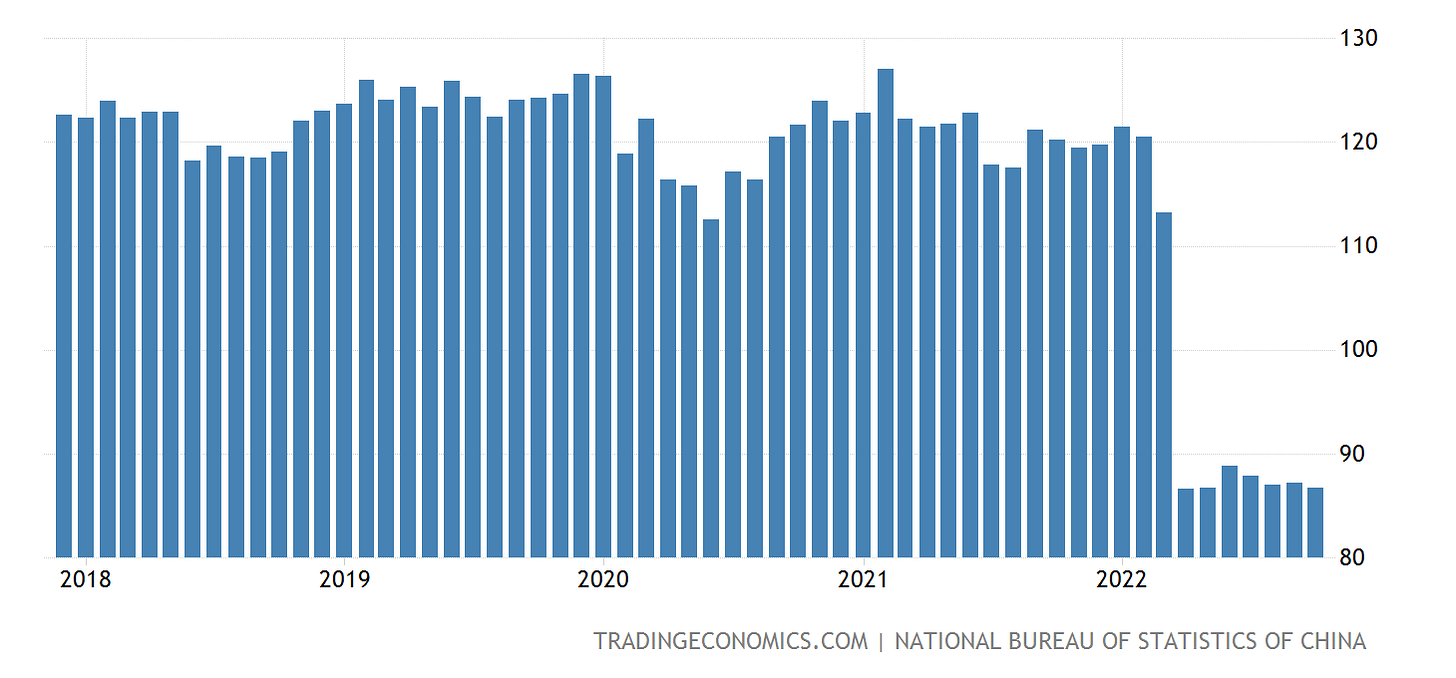

Meanwhile, China’s industrial capacity utilization has been on a downward trend since mid-2021.

China’s factories are slowing down and producing less at the very moment China is trying to “reopen”.

Between COVID and a shrinking economy, it is no great mystery why China’s consumer confidence levels crashed earlier this year, and are still trending down.

While Zero COVID is undeoubtedly a contributor to China’s declining retail sales during the past 12 months, it remains to be seen if the loosening of Zero COVID will reverse that trend.

As I explored the other day, data such as this is a primary reason why China’s relaxing of Zero COVID by itself is not going to reverse China’s current economic contraction.

Reopening into a major COVID wave makes it highly likely that China’s economy is going to get much worse before it can get better.

Nor am I alone in this thinking. This conclusion is shared by a number of China observers, who expect the relaxing of Zero COVID to produce a surge of COVID infections, which must died down before serious economic recovery.

China's shift from tough COVID policies, with its promise of driving an economic recovery next year, will instead likely depress growth over the next few months as infections surge, bringing a rebound only later in the year, economists said.

One major concern with the loosening of Zero COVID: Can China’s fairly brittle and largely inadequate health care systems deal with an unrestrained surge in COVID infections and hospitalizations?

"Compared with other developed countries, medical resources in China are somewhat insufficient," said Nie Wen, a Shanghai-based economist at Hwabao Trust, who has cut his China growth forecast for the first quarter to 3.5%-4% from 5% previously.

Exactly how bad this current COVID wave will be remains to be seen, particularly as it is the first time China has faced an infection surge without imposing swift lockdowns to disrupt the spread of the virus. While the lockdowns themselves failed to stop the spread of the virus, China’s centralized quarantine and isolation efforts did have the paradoxical benefit of shielding China’s regular hospitals from much of prior infection waves. That shield has now been largely removed.

Will China’s healthcare systems be overwhelmed by this latest surge—much like what apparently happened in Wuhan in 2020 when the virus first escaped from China’s virology labs?

Beyond the question of how well China’s healthcare systems will fare with the current COVID wave, however, is the broader question of what will China do—and what will China have to do—to catalyze an economic recovery once the current COVID wave has passed? The relaxing of Zero COVID means China is reopening now, not after COVID has died down again, and the COVID wave all but guarantees China’s reopening will not reverse the current contraction.

Yet China can only reopen once. By the time economic recovery is possible, the stimulative impacts of the reopening will have dissipated and disappeared. Xi Jinping will have to look elsewhere for the means to restore consumer confidence and spur domestic consumption.

Restoration of fuller industrial capacity utilization will likely have to wait until the global economy is done with its contraction, and China’s export customers are ready to start buying more.

Reversing China’s rising unemployment is perhaps the easiest challenge China will face in 2023, for the simple reason that government stimulus measures can easily be used to put people back to work. However, the long term challenge will be for China to stimulate employment in a manner that will help to fuel a sustained economic recovery and expansion.

It is also uncertain what the global economy will look like once China is ready to begin its own economic recovery. The global economy is not merely contracting it is changing, with global trade patterns shifting, and globalism itself retreating. The Russo-Ukranian war has exposed many of the pitfalls of having extended supply chains beyond one’s own borders,

How many countries will adopt Germany’s newfound stance on decoupling and distancing from China simply as a means of economic self-defense?

By the time China is ready to reengage its factories, many of China’s former customers may very well have moved on, and the global export business China needs to recover may not be there when it is ready at last to recover.

In the end, it all comes down to timing. The ideal timing for China’s economic recovery would be for it to happen close on the heels of the current relaxation of Zero COVID. Then the relaxed policies could unleash pent up demand in a surge of domestic consumption, which would go a long way towards restoring not just consumer confidence locally within China, but investor and business confidence in China globally. Economic recovery now would allow China to be able to make the case that it is ready to do business on the world stage now, not down the road. Unfortunately for China, the current COVID wave means the message China will be sending to the world is not that it is ready to do business now, but that it will be ready to do business “soon”—which is not a message that inspires confidence into the long term.

As I said at the beginning, timing is everything. Loosening Zero COVID into a combination COVID wave and economic contraction shows that timing is the one thing Xi Jinping does not have.

Same thing happened in Australia and New Zealand when they dropped their Zero Covid policies; both had big waves. "Virus gonna virus". Zero virus policies might be rational if the virus in question had a double-digit (percentage) fatality rate, but not for one where it's a small fraction of one percent.