De-Dollarization--Fact, Fiction, Or Fantasy?

Some Essential Contextual Points About The Dollar's Status As The "Global Reserve Currency"

This article begins with a shout-out to my reader “Doubting T”, for posing a question that the corporate media has been pushing to the forefront of everyone’s brain housing group lately.

Have you thought out the fate of the dollar as the reserve currency to the world and whether it is net net good for us regular USA citizens? The "hype media" seems to claim sky is falling. Is that true?

The short answer is, of course, that the dollar is not in immediate danger of losing its status as the world’s premier reserve currency, despite the recent corporate media effluvia about the recent trend in “de-dollarization”, and in particular China’s efforts to displace the dollar with the yuan.

The global de-dollarization campaign is gaining momentum, as countries around the world seek alternatives to the hegemony of the US dollar.

China and Russia are trading in their own currencies.

Beijing and Brazil have also dropped the dollar in bilateral trade.

The UAE is selling China its gas in yuan, through a French company.

This, according to some, spells the end of the dollar’s hegemony over global finance.

What does the data say?

First, it is important to understand exactly what is meant by the term “reserve currency”.

A reserve currency1 is simply a currency held by the central banks and major financial institutions of the world in order to facilitate global commerce.

A reserve currency is a large quantity of currency maintained by central banks and other major financial institutions to prepare for investments, transactions, and international debt obligations, or to influence their domestic exchange rate. A large percentage of commodities, such as gold and oil, are priced in the reserve currency, causing other countries to hold this currency to pay for these goods.

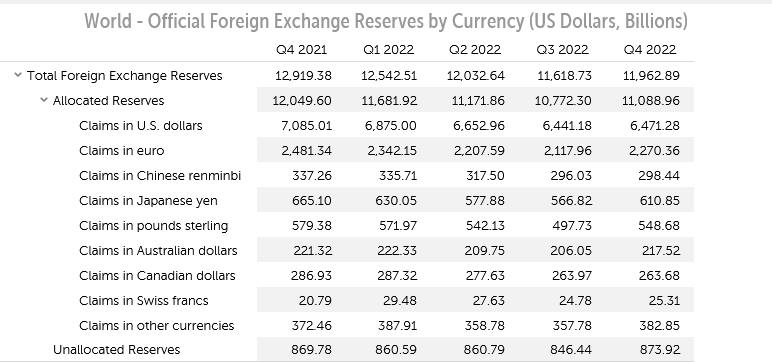

Multiple currencies are in fact used as global reserve currencies, and the two most dominant currencies are the dollar and the euro—almost 79% of all allocated reserves in the world as of Q4 in 2022 are either the dollar or the euro.

As the chart illustrates, the dollar is nearly 59% of all allocated currency reserves in the world. All of the other currency reserves combined do not equal the amount of dollars held throughout the world in reserve.

The dollar achieved its dominant status among the reserve currencies of the world primarily because the US was the only major economy left standing at the end of WW2—at one point the US economy represented 50% of the entire global economy—and thus the US was the major force behind the post-war currency system known as the Bretton Woods Agreement.

The post-war emergence of the U.S. as the dominant economic power had enormous implications for the global economy. At one time, U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which is a measure of the total output of a country, represented 50% of the world’s economic output.

As a result, it made sense that the U.S dollar would become the global currency reserve. In 1944, following the Bretton Woods Agreement, delegates from 44 nations formally agreed to adopt the U.S. dollar as an official reserve currency. Since then, other countries pegged their exchange rates to the dollar, which was convertible to gold at the time. Because the gold-backed dollar was relatively stable, it enabled other countries to stabilize their currencies.

The Bretton Woods Agreement was notable in part because it gave the US dollar a de jure claim as the global reserve currency—other currencies were formally pegged to the dollar and the dollar was in turn formally pegged to gold.

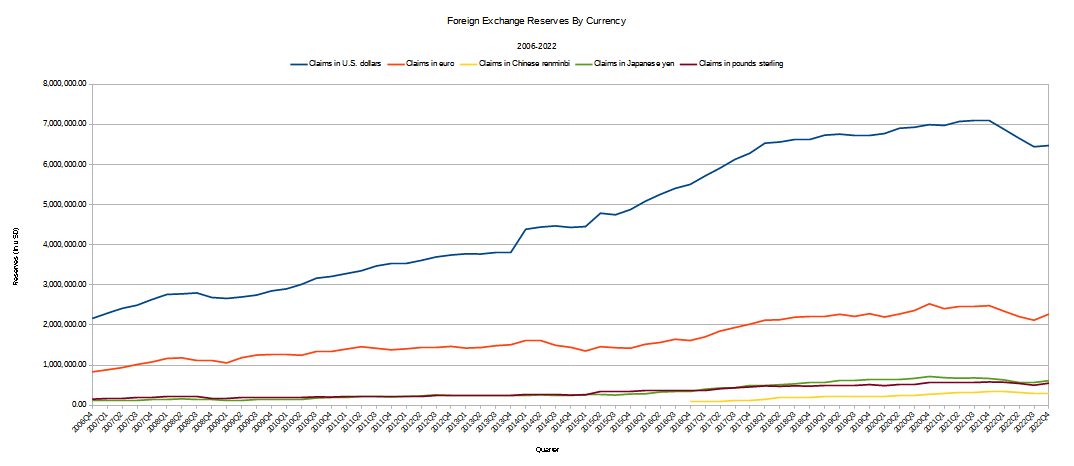

The Bretton Woods arrangements broke down during the 1960s, and by 1971 President Nixon was forced to suspend dollar convertibility into gold—the infamous “closing the gold window”—that ultimately produced the system of floating exchange rates that we have today. Despite abandoning the gold peg, the dollar has remained the premier reserve currency in the world, with over $6 Trillion of currency held in reserve by various nations and banks as of Q4 in 2022.

A few points to consider about the IMF data. While the portion of global reserves held in US dollars declined by 8.7% during 2022, the amount of yuan held in global reserves declined by 11.5%. Total foreign exchange reserves declined by 7.4% overall in 2022. Of the major reserve currencies, only the Swiss franc saw any increase in the amount of currency held in global reserves.

Another crucial data point is the degree to which the dollar has prevailed as the dominant reserve currency year after year after year. If we look at the IMF data from the fourth quarter of 2006 through 2022, the dominance of the dollar has never been marginal or questionable.

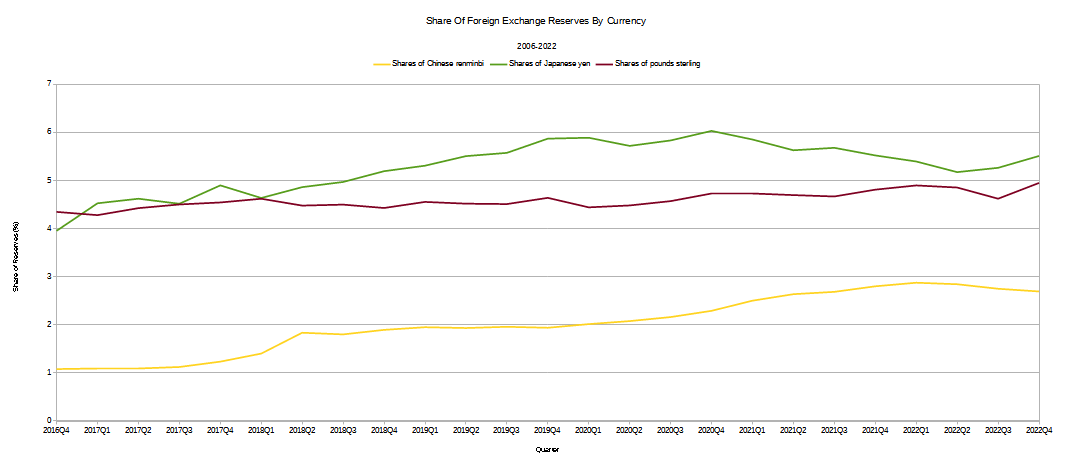

While it is true that, on a percentage basis, the dollar’s share of total global currency reserves has declined, that decline has been far more gradual than the current angst in the corporate media would imply.

Also of note is the fact that, during 2022, the Chinese yuan actually declined as a percentage of global currency reserves.

The currency many are positing as the one about to dethrone the dollar actually became less popular as a reserve currency during 2022.

In order for the yuan—or any other currency—to displace the dollar as the global reserve currency, the amount of yuan held in global reserves has to rise high enough—and the dollar has to sink low enough—for the yuan to exceed the dollar in global reserves. While that can happen, the amount of yuan that would have to be added is nearly ten times what is currently held as foreign reserves around the world.

While such a displacement is theoretically possible, it is not something that is going to occur in 2023, and is highly unlikely to occur at all. There are several substantial reasons why this is.

The most important feature of foreign reserves is that they are portions of the money supply of a particular currency. The dollar reserves of foreign countries and foreign banks held for settling dollar-denominated debts are just that—dollars. Euro reserves are just that—euros.

This means that for any currency that serves as a global reserve currency, the central bank has to ensure that sufficient quantities of that currency are available to satisfy the needs of foreign principals to settle payments and transactions denominated in that currency. The Federal Reserve has to ensure that sufficient dollars are available to satisfy payment and transaction needs not just of entities within the United States, but around the world.

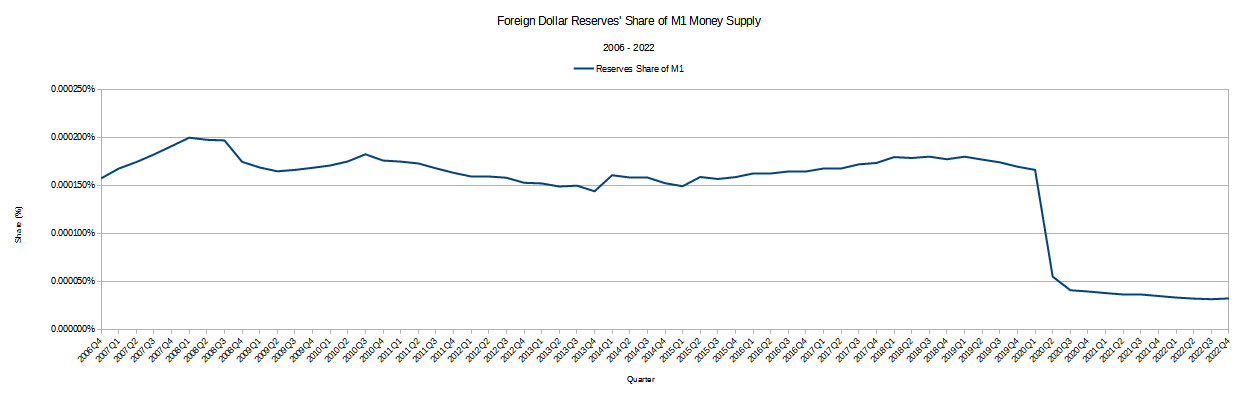

One illustration of just how unimaginably ginormous the US money supply has become is found when we look at the reported totals of dollar-denominated foreign reserves as a share of the US M1 money supply.

Note how the percentage of the M1—already quite small—held as foreign reserves dropped in 2020, at the same time the Federal Reserve increased the money supply by several orders of magnitude. Yet that tiny percentage of the total supply of dollars per the Federal Reserve is by far the largest percentage of the total quantity of foreign reserves held around the world!

However, that foreign reserves must necessarily be part of a currency’s overall money supply also means that reserve currency status—in particular premier reserve currency status such as what the dollar enjoys—requires a steady flow of currency out of a particular country. If the dollars don’t get outside the United States they cannot serve as currency reserve anywhere.

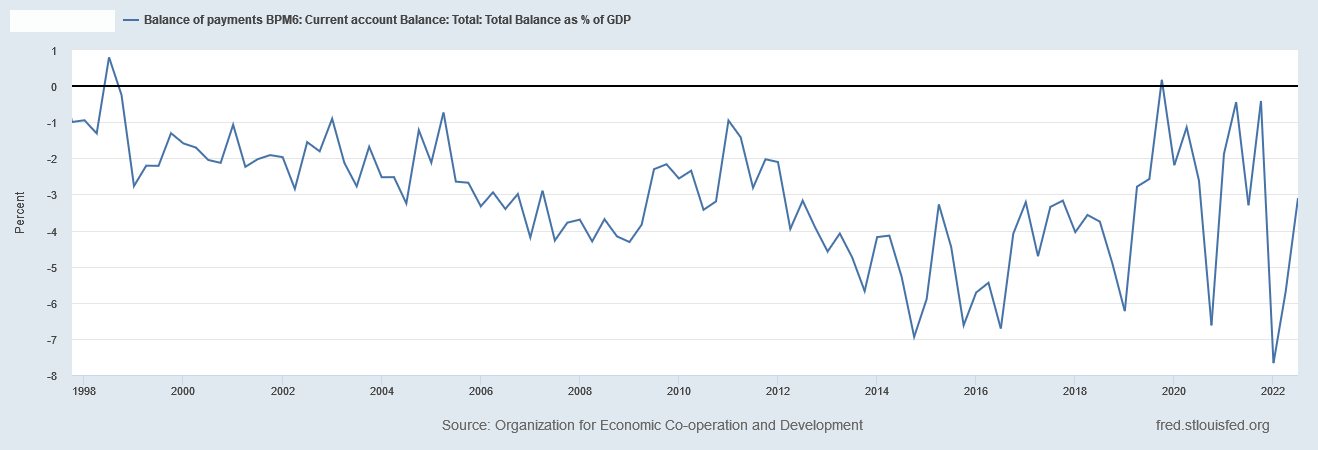

For this reason, the United States, as a result of the dollar being the dominant reserve currency, runs a current account2 deficit, and has for decades. A country's current account is the running record of its transactions with the rest of the world. When the current account is in deficit, a country is paying out more than it is receiving.

For the global reserve currency, this current account deficit is mandatory. No currency can serve as a reserve currency without sufficient quantities of that currency in circulation world wide. A country whose currency is the main reserve currency must always be sending out fresh tranches of currency to the world—and that requires a current account deficit.

As a result, the current account for the United States has run a sizable current account deficit each and every year literally for decades.

Note that China has almost never run a current account deficit. It almost always receives more money than it pays out to the world. If the yuan is to be the global reserve currency, China will have to circulate more yuan than it collects—it will have to run a current account deficit.

There are some indications that China is starting to come to terms with this necessity if they are to realize Xi Jinping’s ambitions to make the yuan a premier global reserve currency. In an address at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, People’s Bank of China Governor Yi Gang assured the audience that China had largely ended its previous practice of frequent direct foreign-exchange interventions intended to control the relative value of the yuan in international commerce.

People’s Bank of China Governor Yi Gang said that Beijing has largely ended regular foreign-exchange intervention, and pursues a policy aimed at enhancing the ease of use of the yuan for Chinese households.

PBOC officials still “reserve the right” to intervene in the market, Yi said in a speech at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington on Saturday. “I haven’t announced” that there is no intervention, he said.

But he said his own perspective is that history shows that “sooner or later” the market defeats the central bank. A slide in Yi’s presentation at the PIIE showed that “in recent years, PBOC has by and large exited from regular intervention.”

China is still reserving the right to resume interventions if it deems it necessary, so Beijing still has a way to go to fully accept the demands placed upon a global reserve currency, but such statements by the PBOC Governor are indicative of at least a start to the needed shift in thinking to embracing perpetual current account deficits for China.

The issue of current account deficits is something many commentators on the dollar’s reserve currency status get exactly backwards.

Jacob Eigner, writing for Georgetown University’s Institute of International Economic Law, epitomizes this inverted thinking about the dollar’s role on the international stage:

From a macroeconomic standpoint, reserve currency status allows the U.S. to maintain current account deficits without commensurate consequences. The U.S. has run a current account deficit in the hundreds of billions of USD for at least the last twenty years since reliable data on the subject has been available. Normally, this current account deficit would raise the cost of borrowing for the government and could be a significant contributing factor to forced austerity policies such as those of the Greek government during the 2008 debt crisis. Yet as other developed countries such as Greece have undergone strong fiscal reforms, forced austerity measures, and even humanitarian crises, in part due to their current account deficits, the American standard of living has consistently risen year-over-year. While America essentially lives beyond its means by far exceeding its income with expenditure, its special status in the global economy has propped up this major imbalance and demonstrates the exorbitant privilege of America due to the special status of the USD.

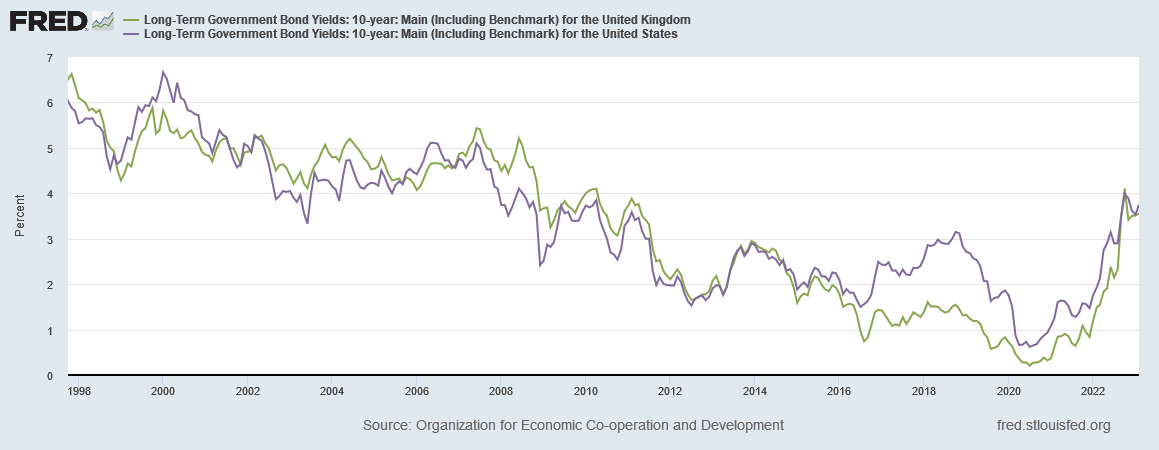

This assertion is simply not supportable. The United Kingdom, whose pound sterling represents but a fraction of foreign reserves as compared to the dollar, has run a current account deficit for decades.

Despite the constant current account deficit, and despite the pound sterling not having anywhere near the global influence of the dollar, the United Kingdom has enjoyed lower interest rates for most of the past decade than the United States.

That current account deficits necessitate austerity and higher borrowing costs is simply not supported by the empirical data—the UK alone disproves that contention.

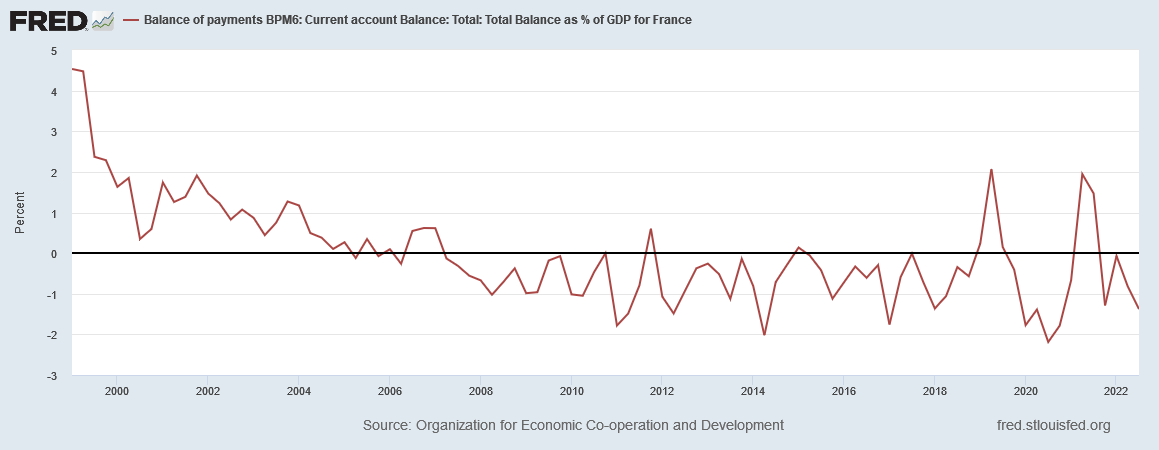

France also routinely runs current account deficits.

France also has had lower interest rates than the US for years.

The belief that the US enjoys an “exorbitant privilege” by virtue of the dollar’s reserve currency status is mainly a propaganda talking point. The one clear advantage the dollar does enjoy over other currencies is greatly reduced exchange rate risk—as most global commodities are priced in dollars, there is less need for the dollar to be exchanged into another currency to complete a transaction. However, the notion that the US enjoys lower borrowing costs and can escape the consequences of a current account deficit by virtue of the dollar’s reserve currency status is simply not true.

There is no firm correlation to be had between a country’s interest rates and whether their current account is in surplus or deficit.

The current account deficit is not a benefit of reserve currency status, but a requirement of it.

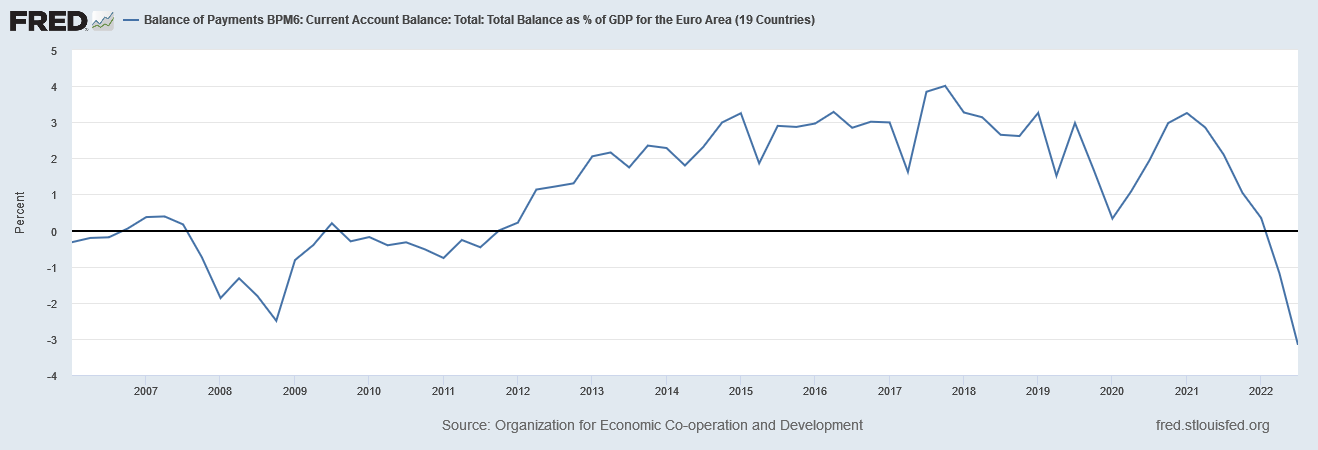

We can see some proof of this when we look at the aggregate current account for the euro area—the 19 countries using the euro as their national currency. From 2006 until 2012, the euro area also ran a current account deficit, and the share of foreign global reserves denominated in euros rose. The euro area has run a current account surplus since 2012 and the euro’s share of foreign reserves has declined.

To be sure, the current account deficit alone is not enough to make a currency a reserve currency, nor is it alone in determining how much of a currency is actually held in reserve. Still, the broad principle remains that global reserve currencies require current account deficits to ensure sufficient quantities of that currency are in international circulation.

Does this mean that the dollar’s role as the global reserve currency is unassailable? Not at all. The mere fact that other currencies besides the dollar are also used as reserve currencies suffices to establish that there are alternatives to the dollar on at least a theoretical basis.

Nor can one completely ignore the efforts by Russia to continue accessing international markets by trading in yuan rather than dollars.

China and Russia, in particular, stepped up their efforts to ditch the U.S. dollar. Russia has been moving away from the greenback for some time, but efforts accelerated after Western sanctions were introduced following the invasion of Ukraine.

Russian President Vladimir Putin said he supports using the Chinese yuan for trade settlements between Russia, Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

The yuan is already the most traded currency in Russia, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. This happened only in February after the yuan surpassed the dollar in monthly trading volume for the first time.

Nor can one fully dismiss the efforts of the BRICS countries to emulate the EU by developing their own common currency, which would then stand as an alternative global reserve currency to the dollar.

BRICS, which is an acronym for five of the world’s leading emerging economies: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, has been receiving extra airtime as of late amid aggressive interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve, which has put pressure on the currencies of other countries.

Babakov highlighted the fact that Russia and India would both benefit from the creation of a common currency that could be used for payments, calling it the “most viable” route to take at this time. “New Delhi, Moscow should institute a new economic association with a new shared currency, which could be a digital ruble or the Indian rupee,” said Babakov.

As ongoing geopolitical tensions over Ukraine and other international flashpoints (Taiwan, anyone?) continues, there an increasing number of countries that would like to have options besides the dollar to trade in. That much is made plain by the corporate media.

Still, the level of dominance any currency must obtain to dethrone the dollar as the world’s reserve currency is not something that can happen overnight. A common currency for the BRICS countries in particular is not going to emerge any time soon—and likely not before the next big global financial crisis.

China has much reform work to complete before it can ever hope to position the yuan as a major reserve currency, whether or not it succeeds in dethroning the dollar. There are signs China is starting to realize that reforms are needed, but it is not at all certain that China will follow through on enacting those reforms.

While there is no shortage of pundits and players who would dearly love to see the dollar dethroned as the global reserve currency, any would-be successor to the dollar has an almost Sisyphean task which it must complete in order to attain reserve currency status.

Ultimately, the reality is as I shared with Doubting T when he first posed his question:

Will the dollar eventually be replaced as the world's premier reserve currency?

Absolutely. And just as soon as a better alternative comes along.

Someday there will be a better option for a reserve currency than the dollar. Nothing lasts forever, and we should not be so blithe as to assume that the dollar’s dominance will continue on indefinitely.

Yet we must also acknowledge the burdens that are placed on any currency aspiring to reserve currency status, and that it will be quite some time yet before any currency new or existing will rise up far enough to overcome those burdens. The dollar’s position as the global reserve currency is almost certain to continue for some time to come.

Chen, J. “What Is a Reserve Currency? U.S. Dollar’s Role and History”, Investopedia. 27 May 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/reservecurrency.asp.

Tuovila, A. “Current Account: Definition and What Influences It”, Investopedia. 21 June 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/currentaccount.asp.

Thank you for this. It certainly educated me. I’m also curious about the digital currency question that Gbill7 poses.

Excellent and reassuring data - I had no idea that the amount of yuan held as reserve currency had *declined* in 2022! That’s certainly not the impression given by the main stream media. Thank you for this.

As flawed as the US government may be, I think the world’s peoples trust in US stability far more than they trust anything said or done by China’s government. As case in point, there was an article in the press a few months ago about Argentina, which was experiencing a 100% inflation rate at the time. The article said that everyone in Argentina used the US dollar as their actual currency, even taking suitcases full of American hundred-dollar bills to real estate transaction.

But a nagging question is: do you see any possible way that a switch to CBDCs could somehow upend the entire reserve currency norm, to our detriment?