De-Dollarization: Is It Real Or Just Another Pipe Dream?

What Are Currency Markets Really Telling Us?

One of the more interesting sideshows to the ongoing stream of negative global economic news has been the more than technocratic concern of the dollar’s recent declines against other major currencies.

The dollar languished near an over two-month low against its major peers on Monday, struggling to make headway on the view that U.S. rates have peaked, with attention now on how soon the Federal Reserve could begin easing monetary conditions.

The dollar’s recent reverses, of course, have been music to the ears of de-dollarization advocates, in particular those who see a potential BRICS currency as having the potential to dethrone the dollar as the premier global reserve currency. According to such narratives, moves such as China’s recent currency swap with Saudi Arabia is furtherance of a global desire to avoid using the US Dollar.

China and Saudi Arabia reached a currency swap agreement worth around $7 billion, marking another step in the dedollarization trend as countries around the world shift away from the greenback.

The three-year deal allows for a maximum of 50 billion yuan or 26 billion riyals.

While relatively small, the deal could loom larger symbolically as Saudi Arabia is the world's top oil exporter, and most global oil trades are conducted in dollars.

That there are countries opposed to US economic hegemony in the world is so mundane a reality as to border on the banal. Throughout history hegemons have always faced challengers to their status, and a good many wars have been fought in furtherance of various countries’ hegemonic ambitions. The foundations of the foreign policy framework known as Great-Power Competition is predicated on an understanding of this1.

Yet we must also remember that all such narratives are first and foremost narratives. They may help contextualize the available data, but they do not replace that data. When the data conflicts with the narrative, it is the narrative that must eventually yield.

With economic turmoil becoming a more relevant part of the global news landscape, we do well, therefore, to pause to consider that the data is actually telling us about the dollar’s place in the world’s currency regimes.

If one follows alt-media outlets such as Watcher.Guru, one might well be convinced that a future BRICS currency is not only inevitable, but its future dominance in global finance is a foregone conclusion.

The BRICS alliance is confident that the soon-to-be-released currency will grow more attractive than the U.S. dollar. BRICS is self-assured that a handful of developing countries will accept the new currency for cross-border transactions after it is launched in the global markets. If developing countries start using BRICS currency, transactions in the U.S. dollar for international trade will come to a halt. The development will prove disastrous to the U.S. economy as billions of dollars will come back to the homeland.

The key word in all such reporting, however, is always that devilish syllable “if”—not for nothing did that one word save ancient Sparta from Macedonian invasion. So many things have to unfold in just the right fashion for such a prediction to come to pass that it beggars believe to simply presume that the outcome is fated to be.

Indeed, Watcher.Guru itself reported at the beginning of October that the US Dollar recently outperformed 20 of the world’s local currencies.

The US dollar is on a winning streak as it dethroned nearly 20 leading global currencies this month. In the last 30 days, the US dollar overtook all BRICS currencies and several other currencies from the West to the East. The US dollar is now ahead of all the currencies that previously threatened its existence. The greenback outperformed currencies from both the developed and developing nations in the last 30 days.

Additionally, we have a report that Argentina, in the wake of Javier Milei’s outsider Presidential election win, will decline membership in BRICS and prioritize the dollar in international transactions.

The high-voltage elections in Argentina have come to an end and right-wing populist Javier Milei is elected president. Milei was riding on the anti-establishment wave and promised a string of changes to bring Argentina’s economy on track. The populist candidate had promised to decline BRICS membership if elected president and support the US dollar for global transactions. Melei used strong words against BRICS members calling China and Russia “assassin governments”.

As Argentina was one of the countries formally invited to join the BRICS consortium at its August summit, such a rejection leaves one to ponder the true prestige and influence of BRICS, with or without any currency ambitions.

Such setbacks for BRICS have done little to stop the anti-dollar narratives. Especially they have not prevented BRICS members—Russia, in particular—from advancing the new currency narrative, proposing it not only as a replacement but actually an improvement over the dollar-dominated reserve currency system.

But there is the problem that when you trade in many currencies, you have high costs of arbitrage of these exchange rates. That is, economic entities need to simultaneously consider the fluctuations of national currencies of different countries.

World prices are still linked to the dollar, so these calculations generate a lot of losses. In addition, we face high uncertainty in pricing, so at the next stage it is necessary to detach the prices of world exchange goods from the dollar and move to quoting world exchange goods in other units.

And what are these other units? This is where the idea of introducing a new world settlement currency arises, which would become a common denominator for the formation of world prices for exchange goods. We are working on this problem.

We have a model of such a currency. It is based not only on a basket of national currencies of the member countries, but also on a basket of exchange commodities. The model shows that this currency will be very stable and much more attractive than the dollar, pound, and euro.

Perversely, this narrative in support of a BRICS currency actually articulates why the dollar has continued as a global reserve currency decades after it was formally severed from gold—economic efficiency. Reliance on the dollar gives global prices at least a veneer of stability across national borders and currencies.

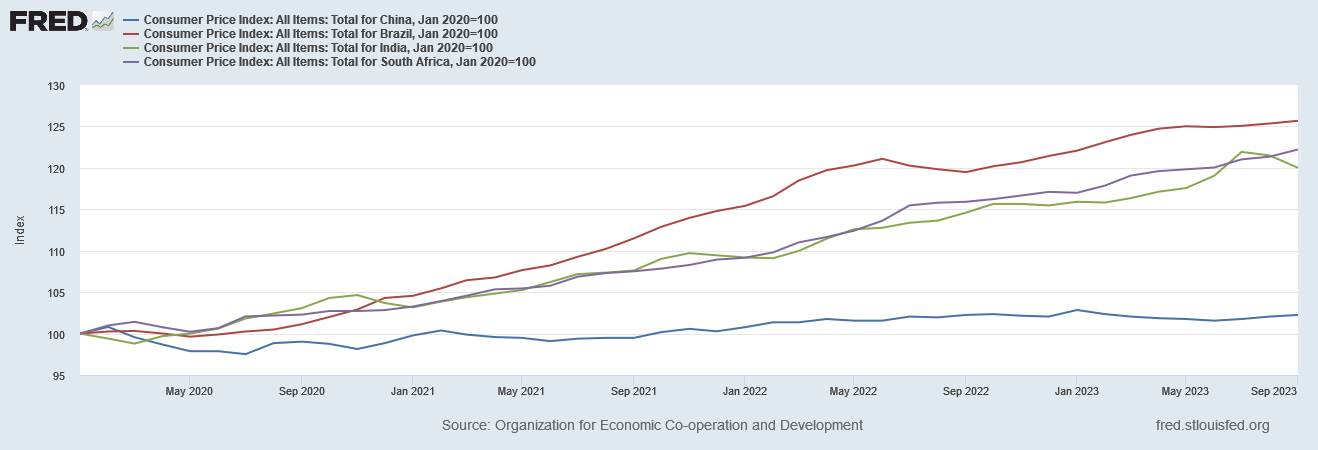

To understand how this can be, consider the performance over the last two years of the Brazilian Real against the Chinese Yuan. The Real has appreciated more than 26% in that time against the Yuan—and these are two of founding members of the BRICS consortium.

In other words, a Brazilian Real today buys 26% more value in Chinese goods and services than two years ago.

Yet over the same time frame the Indian Rupee has actually lost 0.41% of its purchasing power vis-a-vis the Yuan.

For a synthetic currency predicated on a basket of national currencies to be more stable than the reserve currency system, it would have to shift the gains of the Brazilian Real to the Indian Rupee (or vice versa). Failure to do this would put the proposed BRICS currency in functionally the same position as the US dollar, and result in a continuation of the arbitrage costs put forward as a justification for a BRICS currency.

What this particular BRICS currency narrative also overlooks is that this model of a synthetic currency predicated on a basket of national currencies has been tried before with the European Monetary System2. The crux of the EMS was a synthetic currency unit, the European Currency Unit (ECU), to which the participating countries were obliged to peg their national currencies.

Currency fluctuations were controlled through an exchange rate mechanism (ERM). The ERM was responsible for pegging national exchange rates, allowing only slight deviations from the European currency unit (ECU)—a composite artificial currency based on a basket of 12 EU member currencies, weighted according to each country’s share of EU output. The ECU served as a reference currency for exchange rate policy and determined exchange rates among the participating countries’ currencies via officially sanctioned accounting methods.

The EMS ultimately failed because of differing economic agendas among the member nations.

The early years of the EMS were marked by uneven currency values and adjustments that raised the value of stronger currencies and lowered those of weaker ones. After 1986, changes in national interest rates were specifically used to keep all the currencies stable.

A new crisis for the EMS emerged in the early 1990s. Differing economic and political conditions of member countries, notably the reunification of Germany, led to Britain permanently withdrawing from the EMS in 1992. Britain's withdrawal foreshadowed its later insistence on independence from continental Europe; Britain refused to join the eurozone, along with Sweden and Denmark.

At a minimum, Argentina’s potential rejection of BRICS membership stands as a cautionary that not every BRICS nation has the same economic or geopolitical priorities, yet even a synthetic currency system such as has been proposed essentially mandates economic and geopolitical alignment. When that alignment is not present, the synthetic currency will not stand.

However, there is no denying that in recent weeks the dollar has been in retreat against other major currencies, perhaps most notably the Chinese Yuan, against which it has surrendered roughly 2% of its former value.

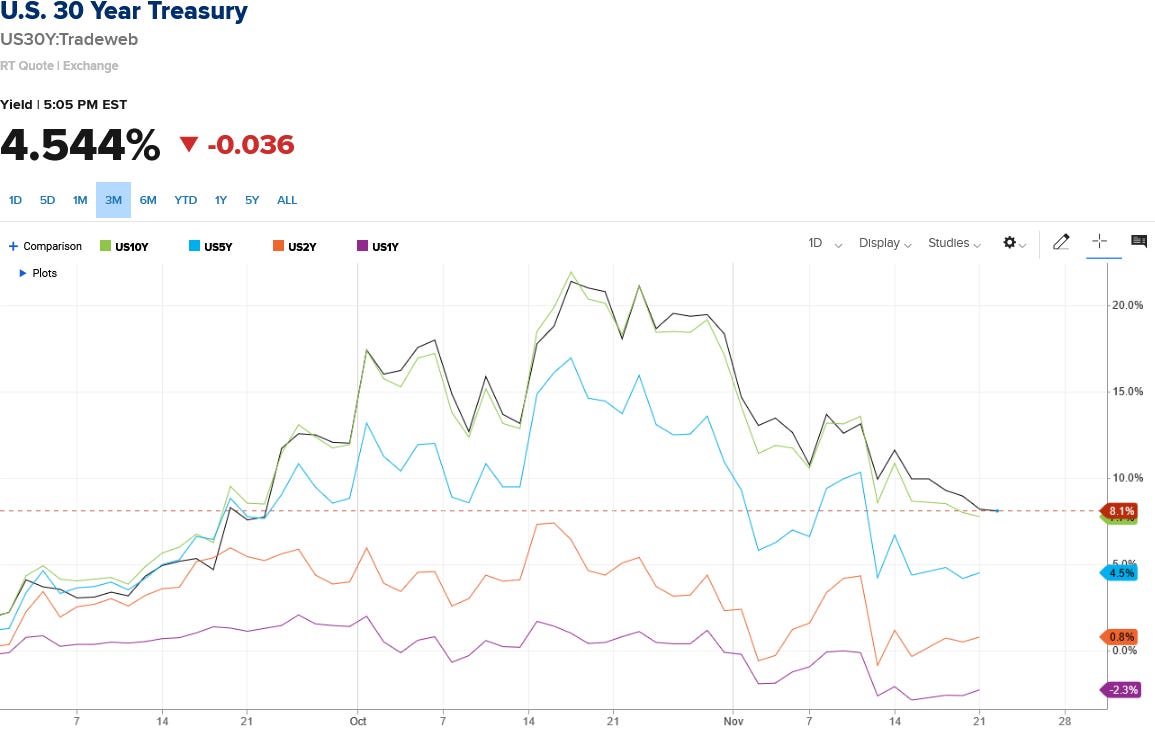

Is this a sign of the dollar fading into irrelevance on the global stage? Not necessarily, as there are some plausible technical reasons for this decline. In particular, recent declines in US Treasury yields, which in turn make US debt less attractive to investors than other sovereign debt, go a long way towards explaining the recent depreciation of the dollar.

Jonathan Petersen, senior markets economist at Capital Economics, said the ongoing fall in Treasury yields is likely the most important factor in gains for the renminbi and yen.

"After all, US bond yields across the curve had been steadily rising and putting pressure on these currencies for much of this year. (Meanwhile, bond yields in Japan and China have not kept pace with the US, either on the way up or the way down)," he wrote. "So, it isn't surprising to us that these currencies have rallied amid the fall in US yields since mid-October." (See chart below).

Cooling of U.S.-China tensions after the meeting last week between U.S. President Joe Biden and China's Xi Jinping may also be helping to lift currencies in the region he said.

Just as rising bond yields contributed to dollar strength over the past 18 months, declining bond yields have contributed to dollar weakness over the past few weeks, with 30-Year and and 10-Year yields in particular having posted significant retreats.

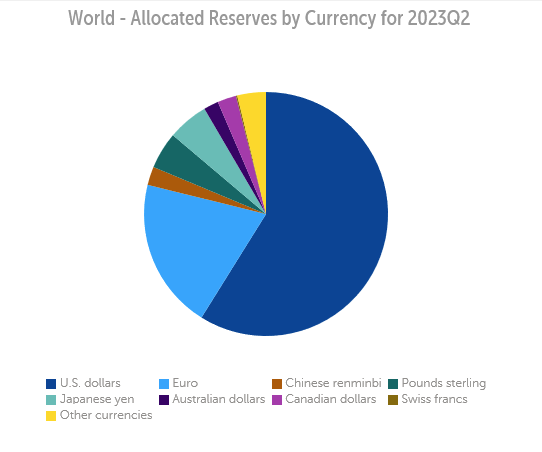

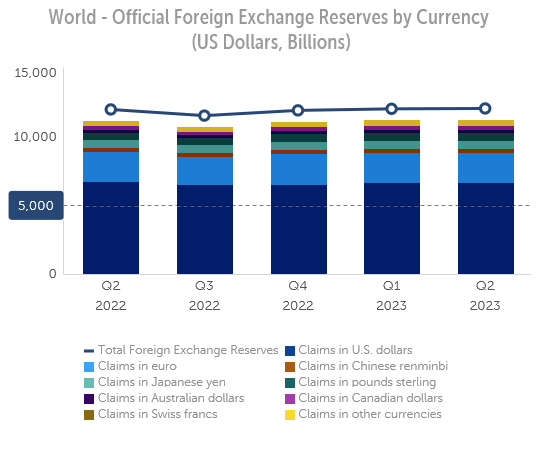

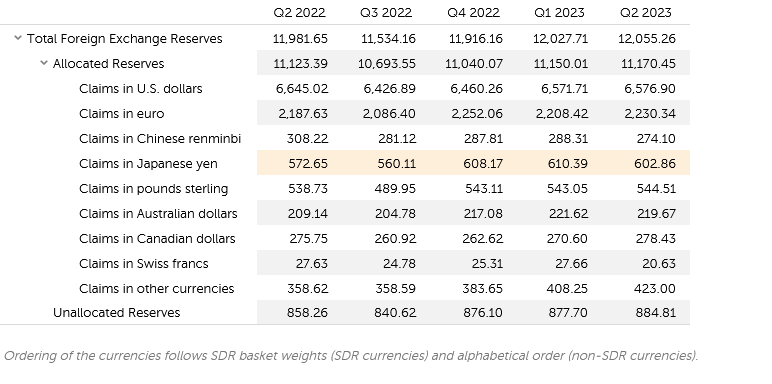

In further argument against the supposed decline of the dollar, we should also note that, as of the second quarter of this year, the dollar still comprised more than 58% of global foreign currency reserves.

Looking at the breakdown by quarter, we also see that the dollar’s ratio among global reserve currencies has been largely stable for several quarters.

In fact, the reliance on the US dollar within the reserve currency system has actually increased for three straight quarters.

Much to the eternal chagrin of de-dollarization advocates, the dollar is showing little sign of losing its economic utility.

While the dollar’s status as a premier global reserve currency is not actually under major threat, we should also not overemphasize the importance of that status. When we look at the valuation trends among major currencies against the dollar over time, we quickly see that the dollar’s weight is, in many respects, overstated.

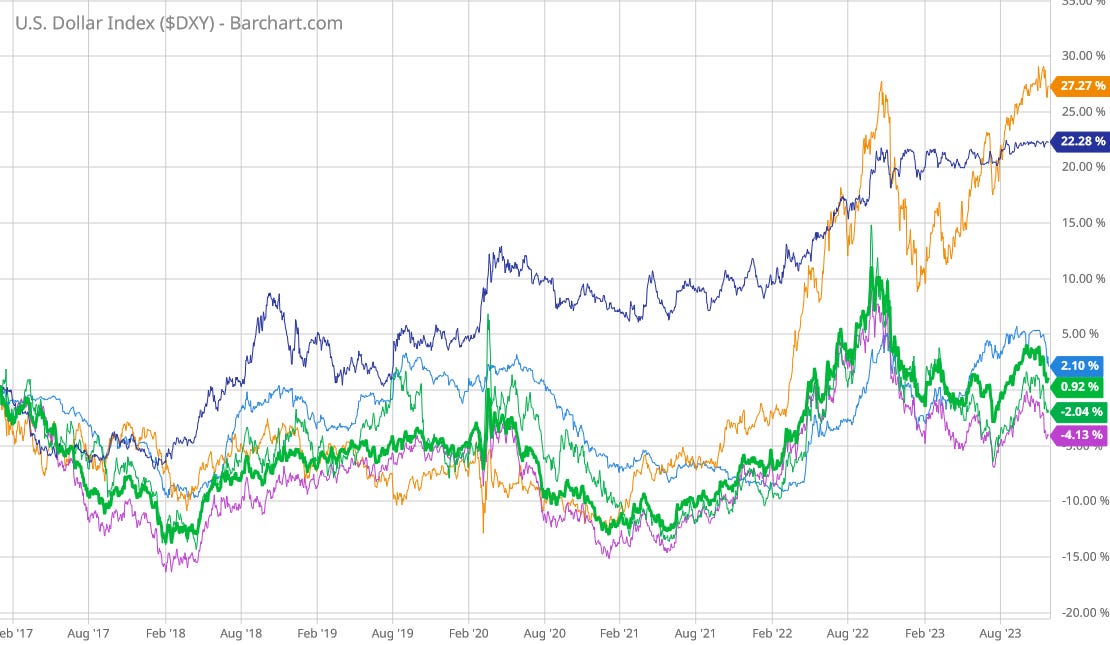

If we look at dollar index trends since January of 2017, we see relatively little appreciation during that time. A small increase in value against the yuan is offset by declines against the euro and the British pound.

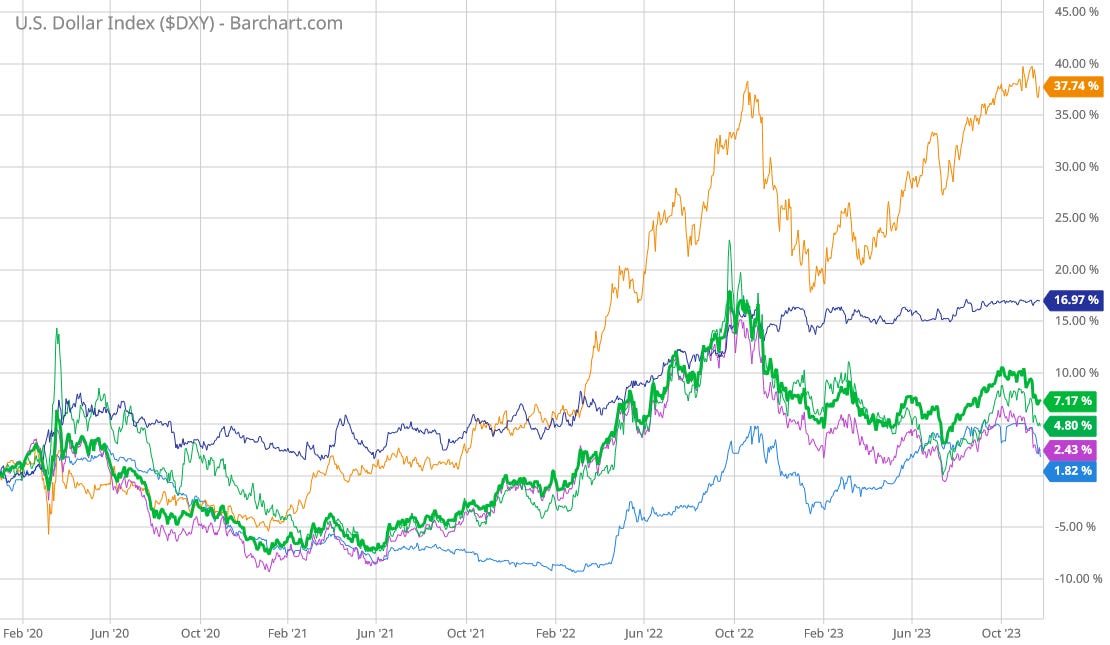

If we come forward to January of 2020, the dollar’s performance is relatively much stronger, although the yuan shows the least currency appreciation.

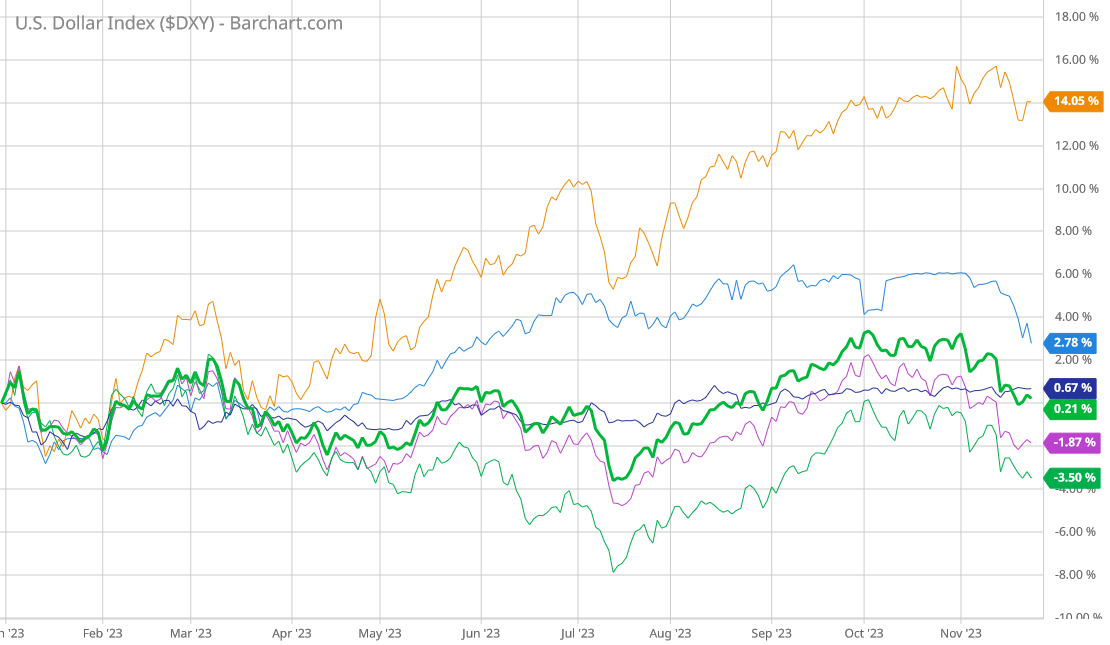

That performance becomes significantly weaker if we come forward again to the beginning of 2023, with the euro and the British pound again gaining more ground than the dollar index itself.

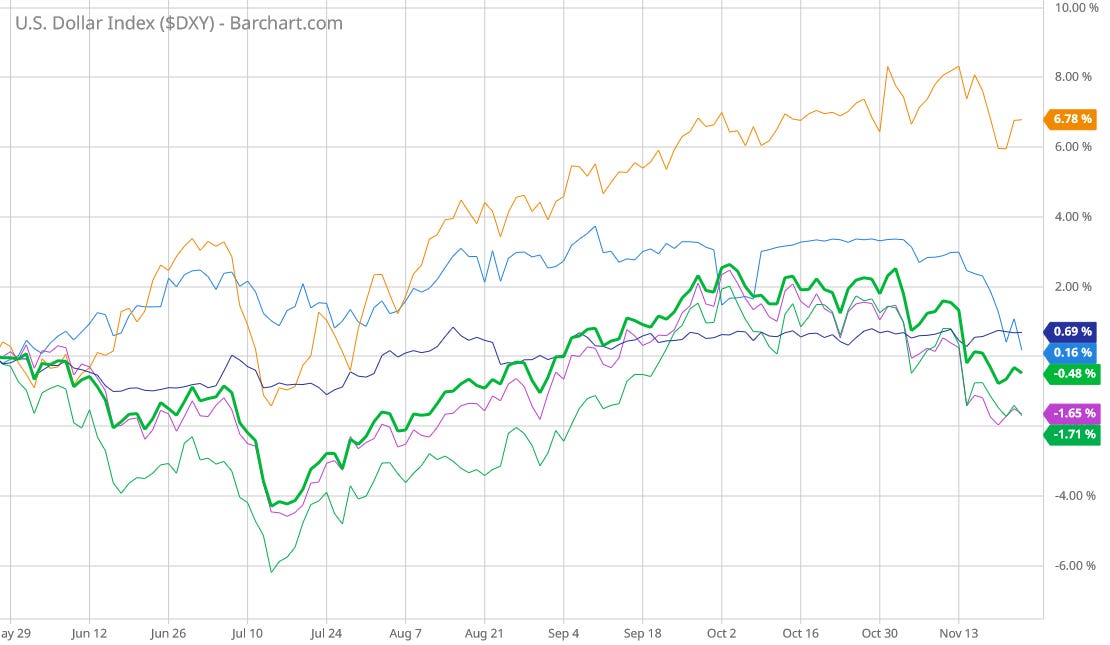

If we look at just the past six months, the dollar has actually declined in value against the dollar index, and even more so against the pound and the euro, while still holding its own (so far) against the yuan.

Yet throughout all of these time intervals, the appreciation or depreciation of the dollar against other currencies is relatively muted. Only with regards to extreme outliers such as Japan do we see significant changes in the value of the dollar with respect to another currency. The shifts in the value of a dollar relative to other currencies is, in almost all cases, smaller than the observed rates of inflation among national economies.

Even for China, which has had a fairly paltry 2% increase in consumer prices since 2020, the increase in the value of the dollar against the yuan comes in at a little over half that over the same time frame.

As much as it may prove galling to de-dollarization advocates, at the present time the dollar-dominated reserve currency system is simply the most economically stable and efficient mechanism for settling international transactions available. The arbitrage effects of valuation shifts between the dollar and various local currencies is, particularly for the BRICS countries, demonstrably less than the overall inflation rate within those local economies. Any alternative to the use of the dollar has to demonstrate greater stability and efficiency, and the collapse of the European Monetary System in the 1990s is a cautionary on the challenges such an alternative must overcome.

We should not conclude from this that the dollar is permanently enthroned as the premier global reserve currency, or that the reserve currency system itself is the economic order of things for all time. If history teaches us anything, it is that nothing lasts forever, and the dollar's heyday of global economic hegemony surely will not last forever.

When a superior, more stable, more efficient alternative to dollar hegemony arises, the dollar will be displaced as the global reserve currency. If a superior, more stable, more efficient alternative to the reserve currency system should emerge, reserve currencies will become a thing of the past.

However, economic forces being what they are, neither should we presume that the dollar will soon fade into irrelevance merely because this or that narrative insists that it be so. At present, the superior, more stable, more efficient alternative to the dollar’s hegemony has not emerged. The lack of that superior, more stable, more efficient alternative makes all talk of de-dollarization still more of a current pipe dream than a coming trend.

The dollar’s day of dominance is not yet finished. Its rule will continue for at least a while longer.

DiCicco, Jonathan M., and Tudor A. Onea. "Great-Power Competition." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. January 31, 2023. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.756

Liberto, D. “What Is the European Monetary System (EMS)? Definition, History.” Investopedia, 2021, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/ems.asp.

"When a superior, more stable, more efficient alternative to dollar hegemony arises, the dollar will be displaced as the global reserve currency."

Right, but for the time being, the Dollar remains the prettiest girl in the brothel.

I have a fuzzy recollection of predictions, twenty-ish years ago, that the Euro would supplant the Dollar as the world's reserve currency. After all, the Euro Zone was the biggest economy in the world. Didn't happen. One reason is that a currency union is not the same as a national currency. There are too many different interests tugging it in different directions all at the same time. A synthetic BRICS currency will have the same problem, and perhaps even more so if it's only used for international trade rather than being spendable locally.