Have residential rental rates finally peaked—and does that indicate that broader consumer price inflation may be close to peaking? Certainly, there are some data points that suggest that rents are starting to cool down, that rental markets will follow a cooling trend in housing markets, which could begin to bring overall consumer price inflation down.

According to rental marketplace Zumper, the national trend in residential rents is leveling off.

National rent prices typically peak during the summer–which, during “normal” years, is the busiest moving season. But Zumper’s National Index is up just 0.5 percent for one-bedrooms and down a whopping 2.9 percent for two-bedroom apartments–a sign that rent hikes are beginning to slow, and a reminder that the pandemic has upended nearly every economic trend in its path.

There are similar signals on a regional basis as well. In Bakersfield, California, although vacancies are almost nonexistent, rent growth has slowed in the most recent period.

The citywide vacancy rate declined to 1.38 percent, from 1.57 percent during the first quarter and 1.76 percent in the fourth quarter, according to a report this month from Bakersfield multifamily housing specialist Marc Thurston at ASU Commercial.

But in a possible sign that there may be a limit to how much local landlords can raise their rents, Thurston's report noted that rent growth across the city actually declined from the first quarter by 5 basis points to reach 3.04 percent in the second quarter.

Is That Really The Trend?

A broader national downward trend in residential rents would be welcome news for the average consumer—if that trend is indeed happening.

While rents may be leveling off in Bakersfield, they are still very much rising in Austin, Texas and elsewhere.

Asking rents surged 48% year-over-year in Austin, Texas —the largest increase on record in any metro area since at least the beginning of Redfin’s rental data in 2019. Nashville, Tennessee, Seattle, and Cincinnati also saw asking rents increase over 30% from a year earlier. Rent growth in Portland, Oregon at (24%) fell below 30% for the first time since the start of the year, causing it to drop out of the top 10.

Chicago posted the third-highest average rent increase in the country, according to Zumper (in the same report that showed rents levelling off nationally), just behind Norfolk, Virginia, and Fresno, California.

The median rent for a one-bedroom Windy City apartment jumped 6.3 percent in June from May to $1,870, an increase of almost a third over the past year, according to real estate website Zumper. Two-bedrooms will set you back $2,230, about the same percentage increase from May and 27 percent higher than a year ago.

Even Zumper’s own data leaves room to doubt the “rents are peaking” narrative. Among markets where rent growth was negative month-on-month, the median decrease was 3%, while the median increase among markets where rent growth was positive month-on-month was 3.5%. There were 57 markets (out of 100) where the rent growth was positive, and only 30 markets where it was negative.

Additionally, real estate brokerage site RedFin notes that the median national asking rent crossed the $2,000 threshold for the first time in May, posting a 2% month-on-month increase (15.2% year-on-year).

Certainly no one would want Zumper’s forecast that rents might be easing off to be wrong. However, the data paints a less than rosy picture for that forecast, and other data suggests that rent growth will still increase for the next few months.

Apartment Vacancies Are At Historic Lows.

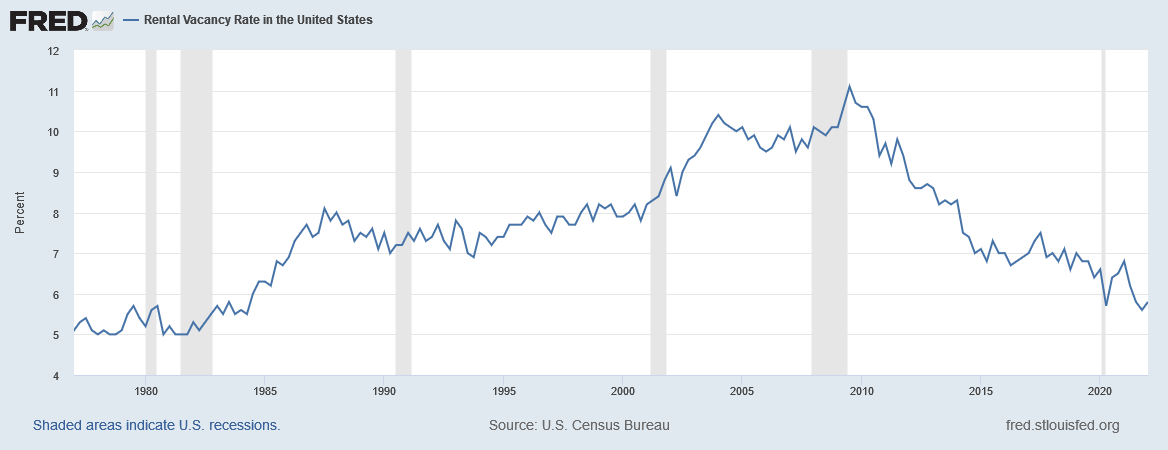

One reason we should not get our hopes up that rent increases are leveling off just yet: apartment vacancies are at historically low levels. Prior to the pandemic, we have to go all the way back to the 1980s to see vacancy rates less than 6%.

While vacancy rates trended up from 1980 through 2009, when they peaked in the 3rd Quarter at 11.1%, they have been trending down ever since, signifying a progressive tightening of rental markets that precedes any of the dislocations caused by the pandemic-era lockdowns.

Additionally, vacancy rates had already rebounded from the 2020 low of 5.7%, and had risen as far as 6.8% in the first quarter of last year before falling again to their pandemic-era low of 5.6%, a level not seen since the second quarter of 1984.

Note that the entire period of the 1970s and early 1980s was a period of low vacancy rates, which did not begin their long trend up until the Volcker recession1.

If we look at the percentage change of the CPI component for the rent of a primary residence for that period2, we see that significant slowing down of rent growth occurred only after that recession was well under way.

Consumer price inflation as a whole also did not peak until after the Volcker recession had begun, and in fact peaked before rent inflation did, albeit by just a few months.

To the extent that we can use the Volcker era as a model for the present stagflationary recession, we should not expect rent inflation to significantly moderate until after we see a leveling off of consumer price inflation overall.

Rent Growth Works Best As A Trailing Indicator For Inflation

Based on how various price indices moved during the late 1970s and early 1980s, it seems most appropriate to view rent growth as a trailing indicator for inflation. When rent growth does finally moderate, it will be confirmation that the consumer price inflation overall has peaked and is on a longer term downward trend.

We should also note from back then that Volcker kept interest rates high for some time after peak rent inflation was reached and a downward trend begun.

While we should be cautious not to read the tea leaves from the 1980s too closely, the Volcker era is the only period of stagflation we have in modern times that is at all comparable to the current situation, and thus it remains our best guide as to what might happen with regards to various inflation components going forward.

Accordingly, if you are in a rental market where rates have fallen recently, count your blessings. Not only is that not the case everywhere, it is quite probable that even those falling rates still have some rise left in them before peak rent inflation is reached.

To borrow from Churchill, we are not seeing the beginning of the end on inflation; at best we are approaching the end of the beginning.

While technically the 1980s saw two periods of recession, I refer to them both together as a single recession, as they occurred during Volcker’s period of historic interest rate hikes to combat consumer price inflation.

While the CPI component for rent of a primary residence is a problematic metric at best, its depth of historical data still gives us a good overall view of larger rent movements for the Volcker era (which, it should be remembered, preceded the most significant restructurings of the Consumer Price Index). To the extent that the CPI rent component is inaccurate, it tends to be understated, rather than overstated, and so any margin of error likely works in favor of my analysis rather than against it.

I wonder if competition is heating up for the renters and that is cooling prices somewhat.

Seems to be a lot of units are going up, at least in my area (Central Savannah Region Area).

These one and two bedroom units are not cheap (comparable to yours above, a little less), but they are filling up.

Glad my house is paid for, but property taxes went up $500, this year, a big increase relative to what I pay with Georgia's homestead exemption ($1300 before).