When we talk about inflation, we tend to think about how expensive everything is, and how frustrating it is to have to budget more closely and sometimes do without.

When we’re talking about food price inflation, however, we do well to remember that what we’re really talking about is food insecurity and, ultimately, hunger—something of which the people of Nigeria are getting brutally reminded.

Nigeria declared a state of emergency that will allow the government to take exceptional steps to improve food security and supply, as surging prices cause widespread hardship.

The move will trigger a range of measures, including clearing forests for farmland to increase agricultural output and ease food inflation, Dele Alake, a spokesman for President Bola Tinubu, told reporters late Thursday. It follows the president’s removal of fuel subsidies and exchange-rate reform, which has seen the naira fall by 40% after its peg to the dollar was removed last month.

Perversely, Nigeria’s experience comes at the same time the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) issues its latest Food Price Index, which claims that food prices are coming down.

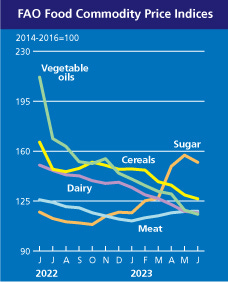

The FAO Food Price Index* (FFPI) averaged 122.3 points in June 2023, down 1.7 points (1.4 percent) from May, continuing the downward trend and averaging as much as 37.4 points (23.4 percent) below the peak it reached in March 2022. The month-on-month decline in the index in June reflected drops in the indices for sugar, vegetable oils, cereals and dairy products, while the meat price index remained virtually unchanged.

One of these two reports is not in touch with reality.

In unpacking food inflation data one must always remember that inflation tends to be a localized phenomenon, rather than a global one. Inflation itself, along with fluctuations in currency valuations, is invariably qualitatively different from one country to the next.

As a consequence, there is a structural limitation to reports like the FAO Food Price Index, as it seeks to represent in a single chart the global state of food price inflation, and thus there is a significant error margin that must be considered when assessing the FAO report in light of a particular country’s experience of food insecurity.

What the FAO report does assert, however, is that, in general, food prices in 2023 are so far much less volatile than they were in 2022, and that many of the extreme spikes in food prices experienced in 2022 have ameliorated. This is plainly illustrated by the year by year comparison chart.

Relative to 2022, food prices globally are, according to the FAO, both lower and less volatile. Moreover, the report also asserts that, even by food category, prices are trending down.

However, like so many inflation data sets, the FAO does not remap the index period to examine relative changes in prices for the current time frame.

If we re-index the category indices to January, 2022, we get a somewhat more nuanced picture of food prices viewed globally.

One thing that becomes apparent by doing this is that not only is sugar more expensive now than it was at the beginning of 2022, but so is meat. Moreover, both dairy and oils have become significantly less expensive, while cereal grains somewhat less so.

In other words, the relative prices of foods has shifted noticeably even as their prices have come down. That has an impact on people’s food buying patterns, and, ultimately, their level of food security.

These differences are emphasized somewhat when we look at the Food Price Index numbers adjusted for inflation—the “real” price index, as it were.

In real terms, the changes in cereals and dairy prices fluctuate with the changes in the overall Food Price Index far more precisely. As a result, the true standouts are oils, meat, and sugar. Essentially, oils are significantly less expensive than other food stuffs, sugar is significantly more expensive, and meats noticeably more expensive.

Additionally, the “real” data confirms that meat is, globally, more expensive now than at the beginning of 2022—3.3% more expensive. Sugar is 32.7% more expensive.

Food overall may be less expensive globally than at the beginning of 2022, but even by the FAO’s own report, not all foods are less expensive than at the beginning of 2022, or even 2023. While the global averages might seem to show relatively small price increases for meat, for example, we should not be surprised if we found some countries where these same prices were considerably higher. Variation has to be expected.

Appreciating this gives us a better context for understanding what is happening in Nigeria. While globally food prices have been in retreat from the beginning of 2022 until now, in Nigeria food prices have been rising.

This is a particularly thorny issue for Nigeria because it is a country that imports much of its food, including staple items. Rising food prices both create and are caused by other issues, such as the core inflation rate, which has risen sharply in 2022 and 2023, just as in other countries.

Attempts to manage inflation and the economy are part of what has precipitated the food crisis. One of the policy changes implemented recently has been the removal of the dollar peg, and allowing the local currency (the naira) to fluctuate freely.

As a result of ending the dollar peg, the naira dropped by 40% at the beginning of June.

Because Nigeria imports most of its food requirements, the devaluation of the naira has translated into a sharp increase in food prices, as it now takes many more naira to buy the same bag of groceries.

Removing the dollar peg may have been advisable from an economic growth perspective, but there is no getting around the exchange-rate shock that produced.

We see similar patterns when we look at Egypt, where food price inflation is at 65% and climbing.

However, we also see that food price inflation in Egypt has largely followed the trajectory of core inflation since 2021.

Unlike in the US, the core inflation rate has largely tracked with the overall consumer price inflation.

Unlike in Nigeria, the Egyptian pound has not risen or fallen dramatically recently.

However, this has not prevented consumer price inflation from taking hold within the economy, and pushing food prices higher along with everything else.

Even while food prices are coming down globally, Egypt’s struggle with rising consumer price inflation means they are struggling with food price inflation as well.

In China, food price inflation has more than doubled—which sounds much worse than it might otherwise be because the increase was from 1% in May to 2.3% in June.

Almost paradoxically, core inflation in China has actually been decreasing, as that country grapples with an unfolding deflation crisis.

However, China’s currency has particularly recently declined significantly against the dollar.

At the same time, China’s wheat crop has been devastated by unusually heavy rains in Henan province.

About one-third of China's wheat is grown in Henan province, earning it the nickname the granary of China. With roughly 30 million metric tons expected to be affected nationally by the rains, out of a forecast bumper crop for all of China of 137 million metric tons, the losses may mean rising grain imports into the world's biggest wheat consumer.

An increased need for food imports coupled with a weakening currency equals a significant uptick in food price inflation.

These exemplars of rising food price inflation in the context of the FAO Food Price Index are but another instance of the contextual problems we see even in the US Consumer Price Index reports each month.

As with the US CPI report, headline food price inflation per the FAO Food Price Index can obscure growing price disparities among food categories as well as regional variations on food price inflation and food insecurity issues.

Thus we see countries such as Ghana struggling with food price hyperinflation during the time frame when the FAO reports food prices globally as either declining or at least rising more slowly.

With many countries depending on food imports to feed their people, rising food prices can greatly exacerbate other economic issues, such as access to foreign exchange reserves—a situation with which Pakistan has been grappling during its struggles to complete negotiations on an IMF bailout of its economy.

The International Monetary Fund’s board approved a $3 billion bailout program for Pakistan which will immediately disburse about $1.2 billion to help stabilize the South Asian ailing economy, the lender said on Wednesday.

Pakistan and the fund reached a staff level agreement last month, securing a short-term pact, which got more than expected funding for the country of 230 million people.

The country has faced an acute balance of payments crisis with only enough central bank reserves to cover barely a month of controlled imports.

Rampant food price inflation makes one of the vital imports—namely food—extremely more problematic in terms of consumption of scarce foreign currency reserves.

Moreover, regardless of what recent food price trends globally have been up until now, there is a high probability they will begin moving up again, as just this week Russia finally terminated the export arrangement by which Ukrainian grain shipments would not be interdicted or attacked by Russia, allowing both Russian and Ukrainian grains out on the world markets. Russia’s termination of the export deal has had an immediate effect on wheat prices, and has the potential to greatly increase grain prices worldwide.

Food price inflation is one of those points where the economic rubber truly meets the road. Food price inflation today becomes food insecurity tomorrow and hunger the day after.

As this handful of country-level experiences of current food price inflation illustrate, extreme and escalating food price inflation can even take place in the context of a contracting, recessionary global economy whose predominant theme in many ways is deflation, not inflation.

Whether the economic theme is inflation or deflation, the economic reality is that both are fundamentally expressions of an unbalanced economy seeking a new equilibrium point. Whenever economies are out of balance, and for as long as they are out of balance, there are going to be people suffering as a result of that lack of balance.

Whether the “experts” addressing inflation are the UN Food and Agriculture Organization or the US Federal Reserve, what they forget time and again in their “expertise" is that prices do not just exist in the abstract. Prices impact people, and price dislocations invariably mean privation and suffering for at least some people.

The FAO reports that food price inflation is decreasing. From this we may safely conclude the FAO “experts” have never been to Nigeria, Egypt, Ghana, nor any other country were food prices are out of control.

I believe that stopping the economic development of Africa and Asia by starving the population would make the globalists happy . They were getting “a lit-tle” too uppity for the likes of the West. The elites don’t want to them be strong enough to build armies and be able to defend themselves . “Equality” is the last thing they want, despite the SDG claims. I think Bill Gates’ main purpose in providing vaccines and birth control is to prevent African babies from being born. But it’s not enough, they have to take away their energy and agriculture too. Or maybe I’m just cynical. 🤷🏻♀️

Unfortunately most people don't give a rat's ass about what happens to the people of Nigeria. Nor does the MSM as well! Until it affects them, most could care less. Thanks for shining a light on it. Linking of course @https://nothingnewunderthesun2016.com/