China’s Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index blew past all expectations in February, surging to its highest level in over a decade.

The official manufacturing purchasing managers’ index rose to 52.6 in February – above the 50-point mark that separates growth from contraction. That marks the highest reading since April 2012, when it hit 53.5.

February’s PMI reading is also higher than the 50.1 reported for January and above expectations of 50.5, according to economists surveyed by Reuters.

Officially, the PMI data shows virtually the all productive sectors of the economy accelerating in 2023, as both Zero COVID and the last COVID “wave” recede into fading memory.

There is quite literally not a portion of the official PMI statistics that is not showing robust growth for China during the first two months of 2023.

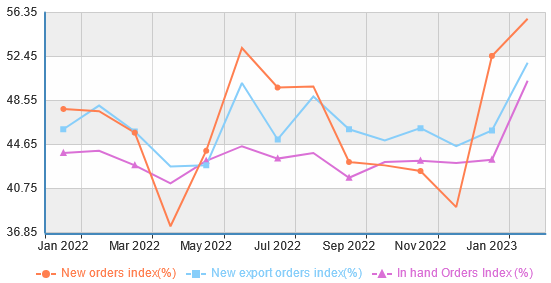

Within the Manufacturing PMI data set, the New Orders Index surged to 54.1, the New Export Index surged to 52.4, and the In-Hand Orders Index rose to 49.3—just below the index boundary between contraction (<50) and expansion (≥50).

The Finished Goods Inventory Index jumped to 50.6, while the Raw Materials Inventory Index moved higher to 49.8, having surged in January to an almost-expansionary 49.6.

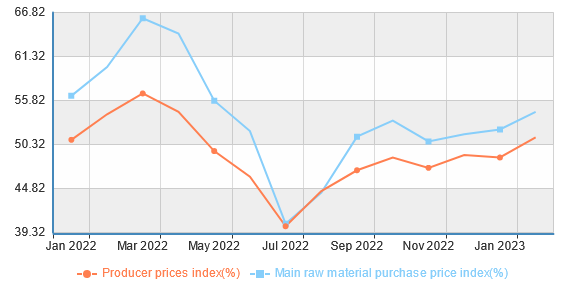

Miraculously (suspiciously?), China is achieving a torrid expansion in manufacturing activity without a proportional surge in producer prices. Both the Producer Prices Index and the Main Raw Materials Purchase Price Index recorded only modest gains in the first two months of 2023.

These PMI stats, taken at face value, are not just good news for China, but positively phenomenal news for China. They portray a national economy that is in full “rebound mode” after coming out of the oppressive lockdowns of Zero COVID.

Even the service sector PMIs are robustly positive.

The Non Manufacturing Business Index jumped to 56.3, with the Employment Index surging to 50.2. The seasonally adjusted Construction and Services PMI numbers also printed significantly higher, at 60.2 and 55.6, respectively.

The New Orders Index within the NMB data surged to 55.8, with New Export Orders climbing to 51.9 and In-Hand Orders climbing to 50.3.

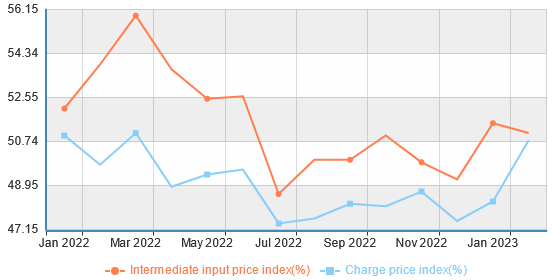

The Charge Price Index rose to 50.8, while the Intermediate Input Price Index actually retreated to 51.1.

Even the unofficial PMIs maintained by Chinese media outlet Caixin showed robust growth in both the Manufacturing and Service sectors during February.

There is no alternative reading to these numbers: they show an economy that is growing by leaps and bounds.

Presumably, even China’s top economic officials are pleasantly surprised by the data.

China’s economy is recovering faster than top officials had expected with the Covid outbreak on reopening passing rapidly through the country, according to a person familiar with the matter, suggesting the government will be restrained in rolling out new stimulus measures this year.

With China’s usual lack of irony, the state-run media outlets are being told to broadcast positive, upbeat messages about the economy as the National People’s Congress gets underway.

In another sign of growing comfort with the pace of the recovery, Chinese state media were told to convey at next week’s National People’s Congress — the annual parliamentary gathering — that leaders are satisfied with the economic rebound and the need for stimulus is moderate for now, another person familiar with the plans said. The government is looking to “hold up” the economy rather than give extra support, the person said.

Yet, there remains some skepticism that China’s economy can sustain this pace of growth for very long, particularly against the backdrop of a global economy mired in a stagflationary recession, with demand for Chinese goods problematic in both Europe and the US, two of China’s main export markets.

The economic outlook remains uncertain, though, against the backdrop of weak global growth and rising interest rates. Demand for Chinese exports from some of the country’s biggest markets like the US and Europe have plummeted in recent months and are likely to remain weak this year. US-China tensions over technology and geopolitical matters have also escalated, weighing on business sentiment.

Growing animosity between Washington and Beijing does very little to further optimism for the future.

Still, a number of multinational companies are reporting positive trends in their China markets.

The world's top consumer and luxury goods companies have seen sales of everything from cosmetics to condoms grow in China since Beijing ended strict COVID-19 curbs, another sign that the world's No. 2 economy is reviving after the pandemic.

Upbeat comments on Wednesday from Reckitt Benckiser (RKT.L), Nivea-maker Beiersdorf (BEIG.DE), Moncler (MONC.MI) and Puma (PUMG.DE) came after data showing China's factory sector grew in February at the fastest pace in more than a decade.

And who can not be upbeat about the economy when condom sales are growing?

Reckitt Benckiser, which makes Nurofen tablets, cold remedy Lemsip and Durex, saw a pick-up in China after a decline in volumes because of lockdowns.

"I have no doubt that the intimate wellness (business) in China is going to perform well," said interim CEO Nicandro Durante, referring to the division which includes KY Jelly and Durex condoms.

The narrative is clear: China is back to explosive growth once again.

Or is it? Not everyone is convinced the numbers are what they appear to be, nor that any current growth trend will be sustained over the longer term.

Yet manufacturing wasn’t the only surprise among the day’s data. The gauge for services activity, known as the nonmanufacturing PMI and a rough measurement of consumption, leapt to a fiery 56.3 — also one of the highest readings in nearly a decade, and above economists’ expectations.

Yet whether it specifically marks an opening of the notoriously tight pocketbooks of Chinese customers remains unclear. Pettis told MarketWatch he expects a temporary revival of consumption, though “it’s still a little early to confirm it. I’d like to see another month of consumption data.”

Many American companies with a significant presence in China are also skeptical of the “reopening”, as the American Chamber of Commerce in China reports in its recently-released Business Climate Survey.

Taken overall, China is no longer regarded by American companies as the primary investment destination it once was. This year – for the first time in the report’s history – less than half of respondents to the Chamber’s 25th annual China Business Climate Survey (BCS) ranked China as a top three investment priority. Meanwhile, 45% of members noted that China’s investment environment is deteriorating, up 31 percentage points (pp) from a year ago and the highest

percentage of members to respond this way in the last five years.

The intimate involvement of the Beijing government—and thus its politics—in the economy is producing a number of issues for American companies seeking to business in China.

• 65% of members say they are unsure or uncertain that China will further open to foreign investment.

• 49% of member companies feel less welcome than a year ago, rising to 56% in the

Consumer sector.

• The top three areas of unfair treatment for foreign companies in China, identified by members, are market access, licensing, and regulatory enforcement.

• Rising US-China tensions remains the top business challenge, cited by 66% of

respondents.

• For a second year, US-China tensions were also cited as top factor contributing to HR challenges.

The degree to which the growing divide between Washington and Beijing will hinder China’s overall economic recovery remains very much an open question.

There are other reasons to doubt the robustness of China’s economic rebound.

Most notably, the contribution of Final Consumption towards GDP growth declined significantly in the last quarter of 2022, and the contribution of exports was actually a net negative.

Only Gross Capital Formation (i.e., infrastructure spending and capital investment spending by private companies) showed a positive trend in 2022.

This makes for a rather problematic platform for the abrupt turnaround China is reporting in its PMI data.

Moreover, while unemployment among workers age 25-59 declined to 4.7% in January, youth unemployment increased to 17.3%.

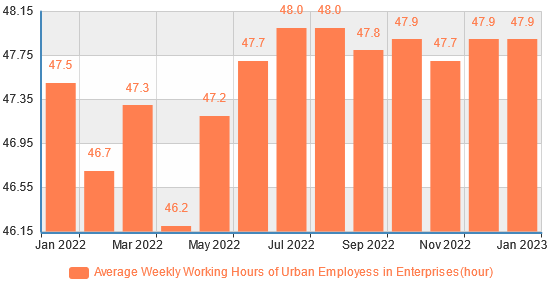

Nor was the apparent increase in manufacturing activity the result of increasing labor hours in January.

If the labor component just isn’t there, sustained rebound in any economic sector is dubious at best.

And we know the labor component is most emphatically “not there.” Over the past three years, China has lost at least 41 million workers.

Some 733.5 million Chinese people were employed in 2022, according to the country’s statistics bureau. That’s down from 774.7 million in 2019. The data reflects a rapid rise in the number of people retiring, likely raising pressure on Beijing to accelerate unpopular plans to raise official retirement ages.

The drop reflects factors such as higher youth unemployment due to the pandemic as well as a shrinking number of people in the “classic age group of the working-age population,” said Stuart Gietel-Basten, a demographer at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

There are few good ways for China to get around the reality that its population is aging rapidly, and it is about to begin losing large numbers of erstwhile workers to retirement, and the younger generations are not in sufficient numbers to replace them.

China’s retirement age has remained unchanged for more than four decades at 60 for men and 55 for female white-collar workers, even as life-expectancy has risen. China experienced a baby-boom during the 1960s, meaning a large cohort of workers will fall out of the 16-59 age group over the course of this decade.

A growing population of retirees and a shrinking population of workers is not the recipe for prolonged economic growth, and particularly not a recipe for a growth of consumption as an economic driver.

Moreover, China is still contending with the fallout from its burst property bubble, which has prompted considerable stimulus spending by both Beijing and local governments.

Since early 2022, over 300 cities have issued support measures for the housing market, including relaxation of various purchasing restrictions. Beihai decreased the minimum down payment from 60% to 40% on households’ purchase of a second property. Cities also included housing-related supporting measures into their policy packages in other areas such as elderly care, fertility promotion or talent attraction.

In Zhengzhou, the elderly were encouraged to move in with their offspring or relatives in the city, enabling the latter to be eligible for an additional housing purchase. In cities with construction suspension and boycotts, local governments set up special funding and departments to help resolve the crisis.

Stimulus aside, however, China also has yet to come to terms with the longer-term ramifications of its declining population—which invariably must translate into a decline in the previously bubbly real estate markets which have been primary contributors to China’s GDP growth in recent years.

In addition, as the Chinese population has started to shrink in 2022 — and aging will accelerate in the coming decades — overall housing demand will soon decline, and revenue from land sales can no longer sustain local finances. China’s urbanization rate also implies the decline of housing demand.

The overall urbanization rate in 2022 was 65.22%. Experience in other countries suggests that, when the urbanization rate reaches 60%, growth in the real estate sector will decelerate both in investment for residential property and in housing prices.

Simply put, China’s shrinking demographics have made it impossible for Beijing to reinflate the property bubble yet again.

With a shrinking labor force, and a shrinking consumer market as a result of population decline, even under the best of conditions the stamina of China’s economic “recovery” would still be in doubt. Coming out of Zero COVID and with a global economic and geopolitical landscape that is fraught with hitherto unimagined risks, it goes without saying that China does not have the luxury of the “best of conditions.”

Even if the economic growth suggested by the January and February PMI data is substantially real, much of the other data contains significant warning signals that deserve at least as much attention as the PMI data.

If the PMI data is valid and legitimate, the Chinese economy is booming. However, the key word in that sentence remains “if”.

Interesting times….

When you light the afterburners, you run out of fuel rather quickly. ;)

I agree, it’s impossible to take ANY info coming out of China at face value - they always have an agenda they’re pushing. But here’s a few things that are always true:

- People want to feel that they’re FREE. So, as China’s standard of living improves, their citizens will inevitably take the material comforts for granted, and fuss more and more for personal freedoms.

- The time-honored way for a Ruler to unite a grumbling populace is to direct everyone’s attention to an external foe - that would be US, folks.

- After a Ruler has invested a ton of money and effort into building big projects, he wants to get a return on his investment, right? I’ve read that China has built huge infrastructure projects - shipping ports, airports, power plants, etc. - in 147 countries now, as part of their Belt and Road initiative. Sounds like gearing up for war to me. China is going to want to get a lot of use out of these projects...

We are in for ‘interesting times’!