Amazon’s latest layoff announcement, in which it stated it would shed some 16,000 corporate jobs, might easily be seen as yet the latest indicator that the jobs recession is getting still deeper. Is it really that, however? Are the layoffs at the country’s number 2 employer a sign that jobs markets in this country are continuing to deteriorate, or are they starting to improve despite Amazon’s job cuts?

The answer is unclear, because the data is unclear.

We should first note that, although Amazon just announced the job cuts two days ago, the cuts are part of a larger workforce reduction plan Amazon had announced back in October of last year, when it said it would shed some 30,000 corporate jobs.

Although 30,000 represents a small portion of Amazon’s 1.58 million employees, who are mostly in fulfillment centers and warehouses, it is nearly 10% of its corporate workforce and represents the largest job cuts in its three decades, surpassing the 27,000 it pared between late 2022 and early 2023.

The job cuts were necessary to strengthen the company by “reducing layers, increasing ownership, and removing bureaucracy” at Amazon, its top human resources executive, Beth Galetti, said in a post.

The reasons cited for the job cuts were all over the place, with Amazon CEO Andy Jassey citing artificial intelligence, a shifting corporate culture post-COVID, and Amazon having overhired during the 2020 COVID Pandemic Panic.

We should also note that Amazon’s human resources head Beth Galetti downplayed any possibility of future cuts, stating that Amazon had no plans to announce further layoffs every few months.

Are Amazon’s layoffs a leading indicator of a worsening job market, or a trailing indicator now that job markets are improving?

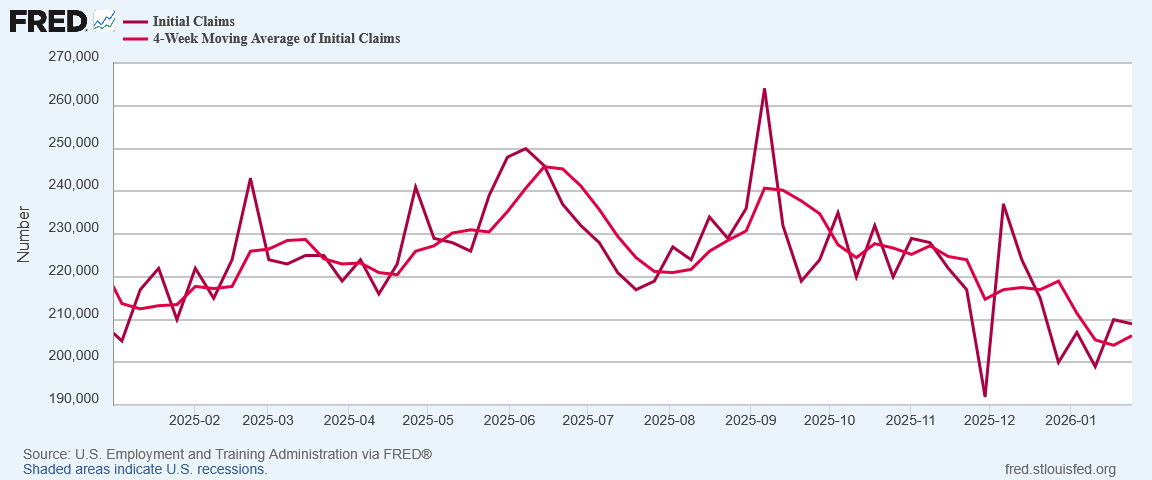

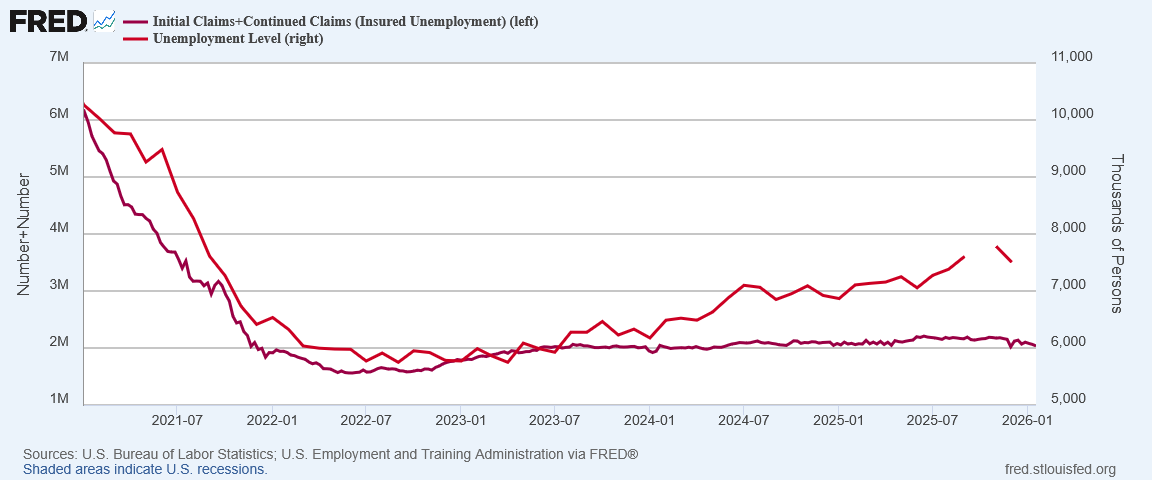

The Labor Department’s tracking of initial and continuing unemployment claims would appear to argue for the Amazon announcement being a trailing indicator.

Initial unemployment claims peaked last September, and aside from a sharp but brief reversal in December, have trended down ever since.

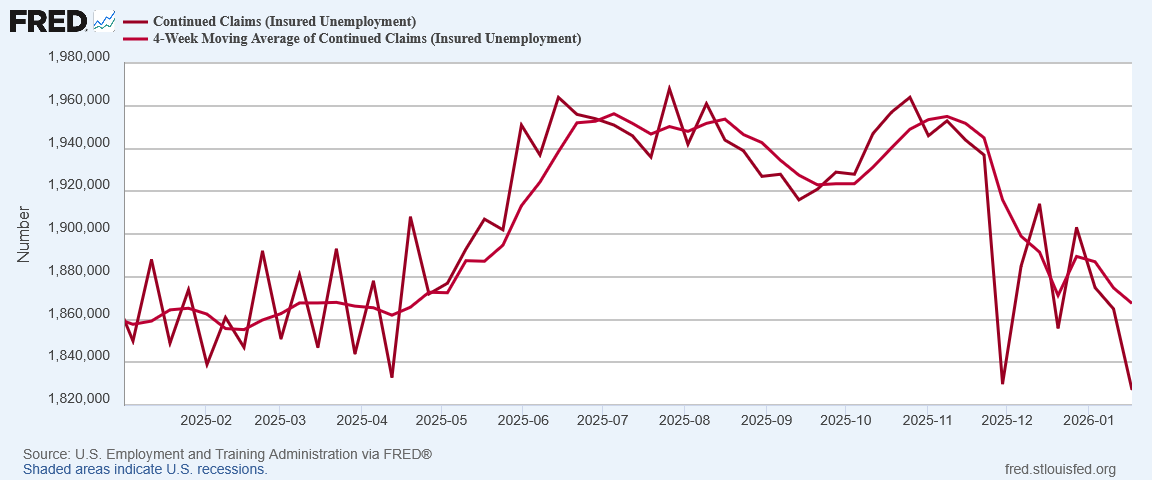

Continuing claims peaked one month later, in October.

While they also underwent a brief surge in December, the overall trend has been down since the peak.

Notably, continuing claims accelerated their decline with the start of 2026, with the headline number of 1,827,000 now below where it was for all of 2025.

At the very least, workers are leaving the unemployment insurance rolls. Whether that means they are moving into jobs the claims data cannot say.

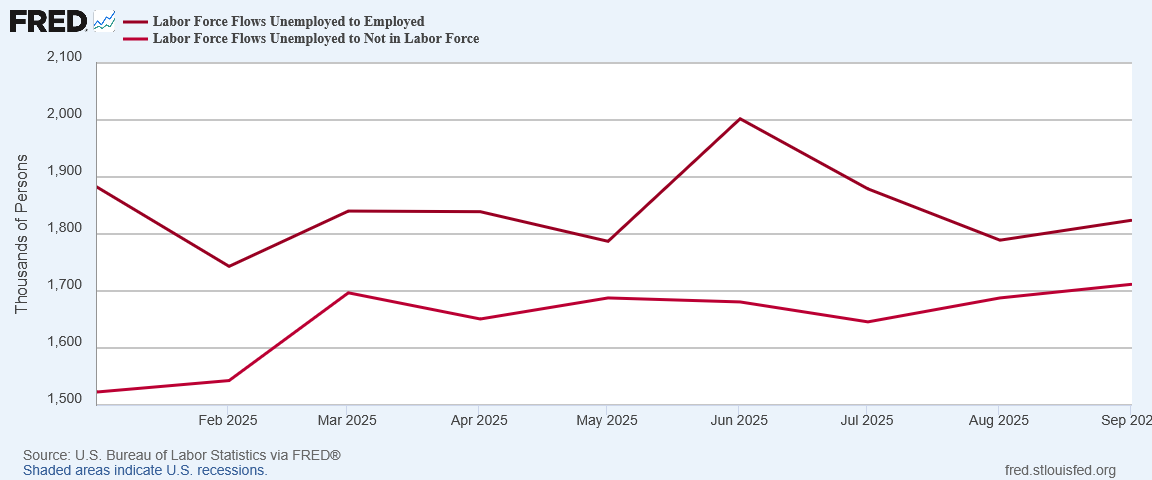

Labor flow data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows a rise in people moving from the Unemployed cohort to the Not In The Labor Force Cohort, a trend which began before the beginning of 2025, reversed slightly in March, and reversed again in July.

While workers moving from Unemployed to Employed rose sharply in June of last year, that labor flow trended down across the first nine months of 2025. We must also note that, because of the Silly Schumer Shutdown, the labor flow data is only through September of last year. Any trends which began in the fall have yet to be recorded by the BLS.

We should also note that the initial claims reports for last week printed above both Wall Street consensus and the Trading Economics forecast. With initial claims of 209,000, the actual tally overshot the predictions by 4,000 jobs, as both Wall Street and Trading Economics guessed there would be 205,000 fresh unemployment claims.

Continuing claims, on the other hand, at 1,827,000 printed some 33,000 jobs below the Wall Street and Trading Economics projections of 1,860,000.

The Trading Economics forecasts for both initial and continuing claims are decidedly pessimistic, with their global macro models predicting 230,000 initial claims per week by the end of the quarter, along with 1,950,000 continuing claims.

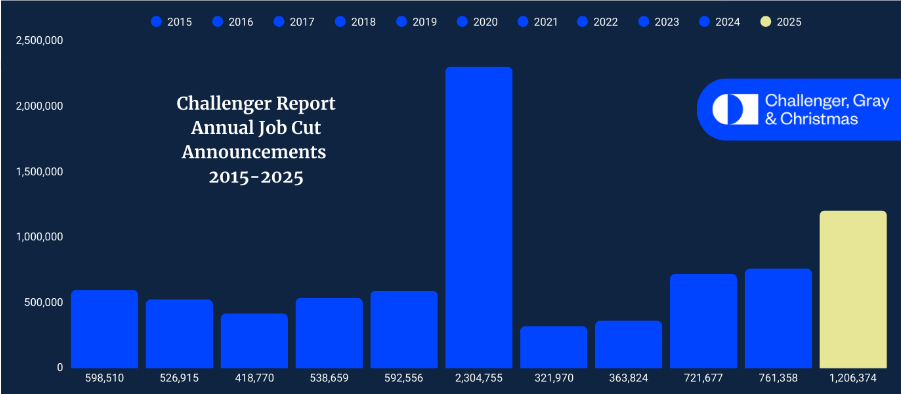

Certainly the Challenger, Gray, and Christmas final Job Cut Announcement Report for 2025 gives no confidence that job markets are starting to get better.

Layoff data tracked by the executive placement firm showed 2025 to be the second worst year for layoffs in the past decade at 1.2 million, with only the Pandemic Panic layoffs of 2020 printing higher.

According to the report, layoffs in 2025 were 58% higher than in 2024, making 2025 not only the worst year in the past decade after the anomalous Pandemic Panic year of 2020, but the seventh worst year for layoffs since 1989.

Equally concerning from the report were the sectors reporting the largest numbers of layoffs. While Government led the way at 308,167—a number many would see as a positive development overall—the tech sector accounted for 154,445 layoffs (a 15% increase of 2024) while layoffs in Warehousing soared 317% from 2024 levels to 95,317.

The hiring side of the report gave little reason for optimism. While employers announced plans in 2025 to hire some 507,647 workers, that was a 34% drop from 2024, and the lowest total for the year since 2010.

These are not signs of an improving labor market.

Yet the report is not all negative. As negative as the data for the entire year was, the monthly data within the Challenger report gave some reason for a little hope, as December’s layoffs numbers were a reduction from November’s.

Andy Challenger, the firm’s Chief Revenue Officer, saw the December numbers as a potential positive sign.

The year closed with the fewest announced layoff plans all year. While December is typically slow, this coupled with higher hiring plans, is a positive sign after a year of high job cutting plans,” said Andy Challenger, workplace expert and chief revenue officer for Challenger, Gray & Christmas.

Hiring plans were up in December relative to both November as well as December, 2024.

If the hiring plans come to fruition, that would be some very welcome news to America’s long-beleaguered labor markets.

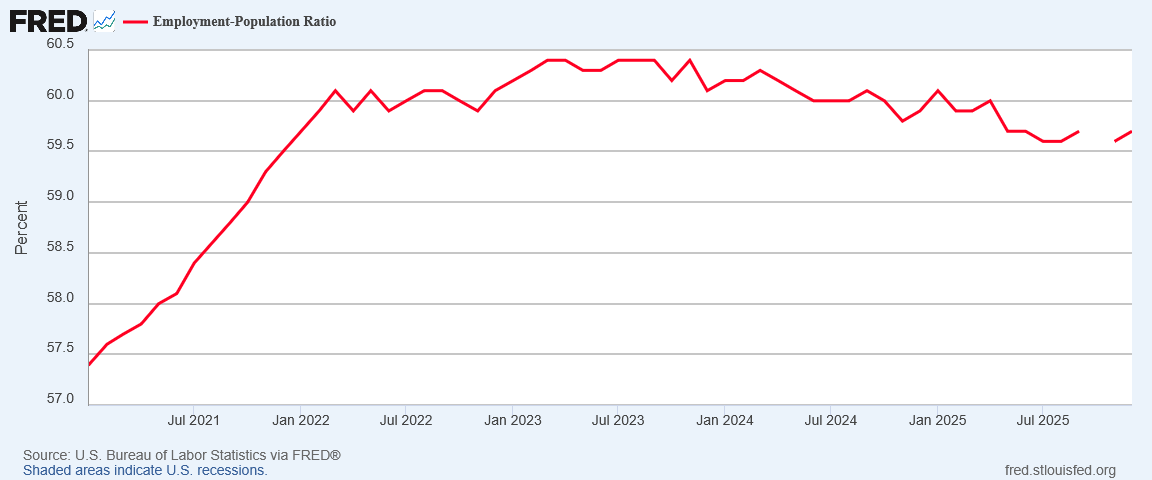

There is no disputing that the long-term employment trend in this country has been negative for quite some time. The Employment-Population Ratio began declining post-Pandemic in the summer of 2023.

Thus far the data has not shown a sustained trend reversal.

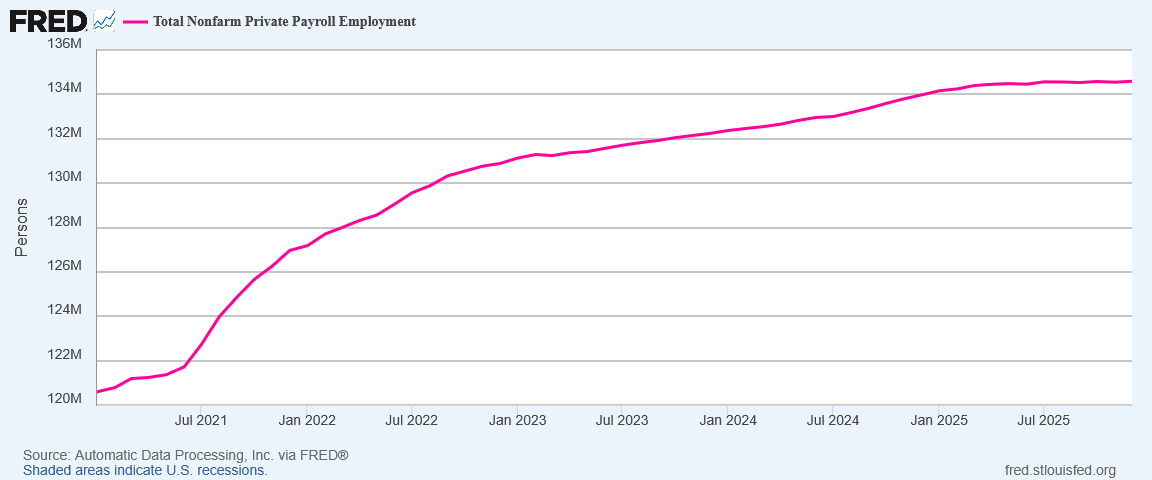

ADP’s private payroll metrics also show employment growth stalling in mid-2025.

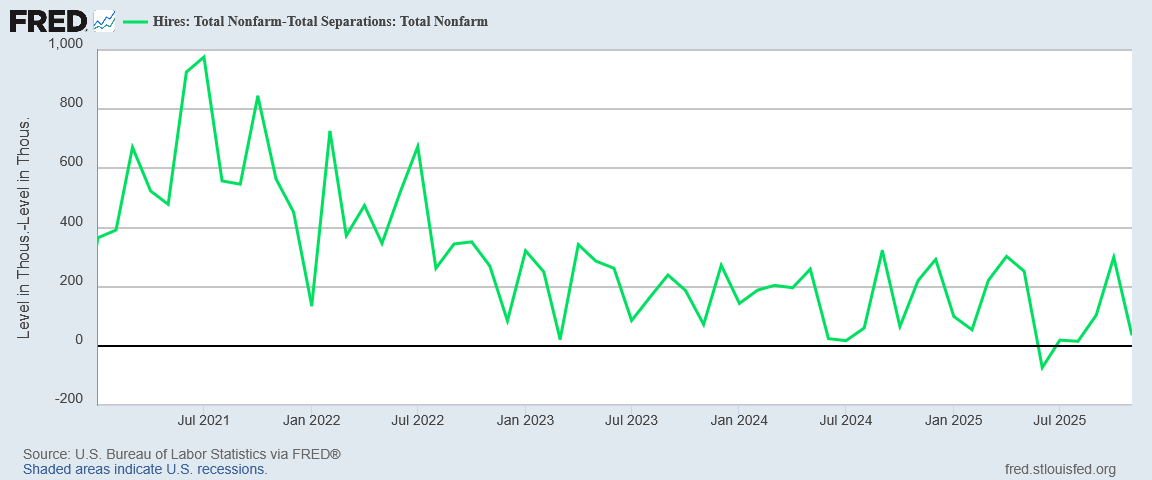

At the same time, the BLS Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey data shows net hiring (aggregate hiring less aggregate layoffs), steadily declining since the summer of 2021.

We should also note that the unemployment claims data itself may not be an accurate bellwether for overall unemployment. While unemployment claims themselves largely trended in the same fashion as the unemployment level in the BLS Current Population Survey, the trends diverged noticeably in 2024, with the unemployment level trending higher significantly faster than the claims data.

While unemployment claims are improving in this country, their overall impact on jobs markets seems to be fairly muted, at least in the past couple of years.

Are the declining unemployment claims an early indicator of an improving jobs market? We certainly should hope that is the case. This economy has endured a jobs recession for over two years, since late 2023. An end to the labor market toxicity would be most welcome.

Increased hiring plans may be a complimentary signal to the decreasing unemployment claims, which would make that part of the Challenger Report a confirming positive signal.

As I have said numerous times previously, without job growth all talk of America’s “Golden Age” is just wishful thinking.

No matter how much GDP growth the statisticians create, without job growth there can be little wage growth, and without wage growth any increase in this country’s overall wealth cannot flow across the broader cross-section of the population. In order to maximize the number of people participating in any increase in this nation’s prosperity, this nation must increase its store of workers.

Period. End of Sentence. End of Discussion.

Should we expect the jobs America needs to be created in 2026?

While we should always hope for an improving employment outlook in the United States, the reality of the unemployment claims data does not let us jump to that conclusion. So far the declining unemployment claims have not translated into increased hiring. So far the upward trend in unemployment has not (yet) been reversed.

The latest unemployment claims data might give us some hope, but Amazon’s layoffs are a reminder that the jobs data has to get much better across the board before we can comfortably feel the jobs recession is at an end.

I wonder if Powell saw this data and figured he’d hold the FFR in order to screw Trump?

“The answer is unclear, because the data is unclear.”

Thank you for this, Peter. When the data is muddled, opportunistic politicians jump on partial data and try to manipulate us into supporting their agenda. I much prefer some level-headed genius like you analyzing the data and giving the factual picture - which, in this case, is an unclear picture. Now I can wait for the clarifying data that will come in time. No problem.

You have rare credibility, Peter!