Jobless Claims Are Rising While The Economy Is Growing?

More Data Cutting Against The Narrative Of Economic Growth

As I outlined yesterday, while the “official” prognosis for the US economy is one of reasonably robust growth, a full analysis of the available data paints a far more muddled and inconclusive picture.

Not only are the industrial and manufacturing statistics pointing to various levels of contraction, but there is another factor also arguing against robust economic growth: rising jobless claims.

In the week ending December 3, the advance figure for seasonally adjusted initial claims was 230,000, an increase of 4,000 from the previous week's revised level. The previous week's level was revised up by 1,000 from 225,000 to 226,000. The 4-week moving average was 230,000, an increase of 1,000 from the previous week's revised average. The previous week's average was revised up by 250 from 228,750 to 229,000.

The advance seasonally adjusted insured unemployment rate was 1.2 percent for the week ending November 26, an increase of 0.1 percentage point from the previous week's unrevised rate. The advance number for seasonally adjusted insured unemployment during the week ending November 26 was 1,671,000, an increase of 62,000 from the previous week's revised level. The previous week's level was revised up 1,000 from 1,608,000 to 1,609,000. The 4-week moving average was 1,582,250, an increase of 43,250 from the previous week's revised average. The previous week's average was revised up by 250 from 1,538,750 to 1,539,000.

More people out of work is generally associated with economic contraction, not economic expansion.

To be sure, jobless claims are still at near multi-year lows, which mitigates the overall impact of the increase in such claims.

Still, the reality is that initial jobless claims, on both an unadjusted and a seasonally adjusted basis, have been increasing steadily since late September.

The latest rise in jobless claims is far from a statistical aberration; it is a continuation of an established trend. More and more people are being put out of work.

Continuing claims show a similar trend.

Since September, more people are being put out of work, and more people are remaining out of work.

Again, this is not a statistic that is easily reconcilable to the notion of projected 3.4% growth in GDP for the current quarter.

Intriguingly, despite the rising numbers of initial and continuing jobless claims, the number of unemployed in this country officially dropped during November.

One part of the explanation why is undoubtedly that, while the number of workers that flowed from both the employed cohort and the not in labor force cohort to the unemployed cohort dropped, the number of workers who existed the labor force in November rose.

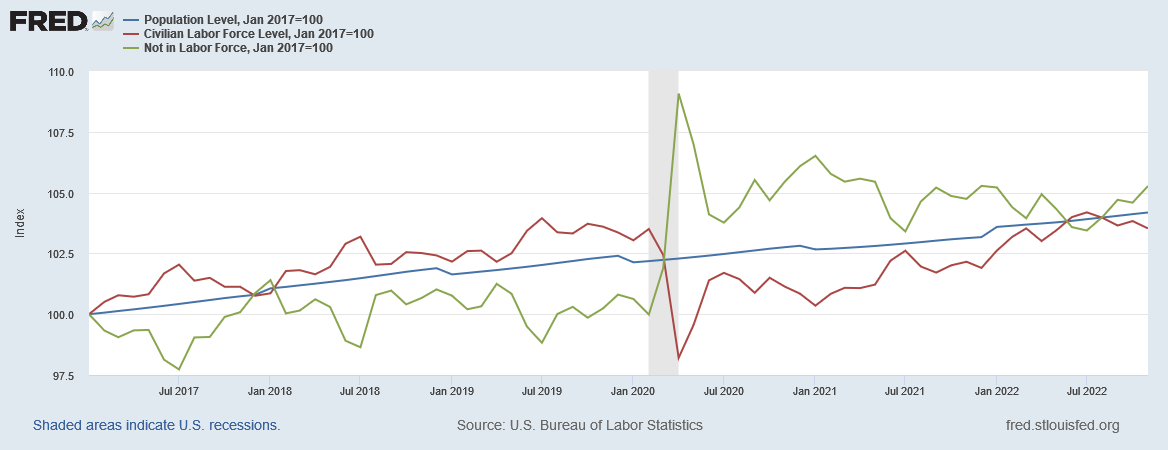

Overall the not in labor force cohort has been increasing faster than either the civilian non-institutional population cohort or the labor force cohort since the pandemic lockdowns in 2020.

The relatively slower growth of the labor force is what is contributing to the appearance of a “tight” labor market, even as jobless claims rise. Particularly in the month of November, more workers moved to the sidelines and exited the labor force than were either employed or looking for work.

The perception of labor tightness is amplified by net hires and separations remaining largely at historical levels even as the number of reported job openings has surged since early 2021.

Instead of the number of job openings pulling workers back off the sidelines and into the labor force, the job openings are remaining unfilled, and hiring and separation patterns are largely unchanged.

Again, the lack of rising labor force participation is not easily reconciled to a forecast of robust economic growth. In fact, declining or stagnant labor force participation particularly when already at a low level, is indicative of economic contraction and stagflation rather than economic expansion.

While economists argue that wage growth in the US is above the historical averages, and that this is helping to fuel consumer price inflation, the reality is the exact opposite: consumer price inflation is fueling wage growth, but not enough for wages to keep pace with inflation.

This steady erosion of real wages and purchasing power throughout late 2021 and all of 2022 is potentially another factor encouraging workers to move to the sidelines. In a very real economic sense, working is costing workers real dollars of purchasing power.

This steady erosion of real wages is compounding the lingering effects of the pandemic lockdowns, which disrupted child care arrangements and encouraged workers to remain home to tend to ill family members, many of which disruptions are being reported as very current and very real phenomena.

The dichotomy of job growth combined with a shrinking pool of workers underscores the tensions facing the U.S. economy at a precarious moment. The Federal Reserve wants to put the brakes on the economy and cool the labor market — yet employers are pulling out the stops to find workers as many remain sidelined due to a combination of sickness and child care issues for parents. On top of that, baby boomers continue to retire in the millions each year.

With work becoming an increasingly uneconomic proposition, the incentive to stay out of the work force to attend to sick relatives is inherently increased.

The unalterable reality of the US labor force is that it is declining relative to the total noninstitutional population. Inflation and disruptions to prior work and child care patterns have distorted the incentives for work, and even 5.1% year on year wage growth is not enough to overcome the increased barriers and disincentives for working.

A growing economy is one that pulls workers back into the labor force; we do not have that economy at present.

A growing economy is one that has declining jobless claims; we do not have that economy at present.

A growing economy is one where wage growth exceeds consumer price inflation; we do not have that economy at present.

A growing economy is one where net hires rises to match reported job openings; we do not have that economy at present.

The likely conclusion to be drawn from these statements is that we do not have a growing economy in the US, which makes the Atlanta Fed’s nowcast projection for 3.4% GDP growth in this country look increasingly unrealistic and fictional.

Well, I remember when a new Corvette, 1971 I believe, was $5495.00 sitting in the showroom.

I also remember, as a little tyke in the back of my moms Falcon, early 60's (??) and the pump said GAS WAR and it was 19.9 cents a gallon.

Wages haven't gone up that much!