PCE: Inflation Cools A Little, Incomes Are Still Shrinking

These Are The Results The Fed Has To Show For Catalyzing The Banking Crisis. Were They Worth It?

This much positive may be fairly said of the Personal Income and Outlays Report for February 2023: consumer price inflation is moving in the right direction—down.

From the preceding month, the PCE price index for February increased 0.3 percent (table 9). Prices for goods increased 0.2 percent and prices for services increased 0.3 percent. Food prices increased 0.2 percent and energy prices decreased 0.4 percent. Excluding food and energy, the PCE price index increased 0.3 percent. Detailed monthly PCE price indexes are presented on Table 2.4.4U.

From the same month one year ago, the PCE price index for February increased 5.0 percent (table 11). Prices for goods increased 3.6 percent and prices for services increased 5.7 percent. Food prices increased 9.7 percent and energy prices increased 5.1 percent. Excluding food and energy, the PCE price index increased 4.6 percent from one year ago.

Unfortunately, that’s about the extent of the positive that may be fairly said. Everything else…is not quite so positive.

In one sense, the PCE inflation numbers were a pleasant surprise, as they came in below most analysts' expectations. The consensus among the economists for the major banks anticipated monthly inflation at 0.4% and yearly “core” inflation at 4.7%

Core PCE is expected to stay at 4.7% year-on-year while rising 0.4% in February (MoM). The headline is seen increasing by 0.2% in February, and a slowdown in the annual rate from 5.4% to 5.3%.

With the headline metric at 5%, the “core” metric at 4.7%, and the monthly metric at 0.3%, the data came in better than expected.

Still, the improvement in inflation is strictly marginal, and arguably insufficient to give the Fed much comfort that its inflation-fighting strategy of causing a recession is paying off at last (with good reason—it isn’t). Despite this, Wall Street is once more anticipating future rate cuts and a monetary policy of easing rather than tightening before the year is out.

The Fed’s own unofficial projections released last week pointed to perhaps one more increase this year and no reductions. However, traders expect cuts this year, with end-year pricing for the federal funds rate at 4.25%-4.5%, half a point below the current target range.

While inflation has ebbed in some areas, it has remained pernicious in others. Shelter costs in particular have risen sharply. Fed officials, though, are looking through that increase and expect rents to decelerate through the year.

Still, inflation is likely to remain well above the Fed’s 2% target into 2024, and officials have said they remain focused on bringing down prices despite the current bank turmoil.

The optimism overlooks the sobering reality that this data does not mesh with the Fed’s stated criteria for even considering a pause in hiking.

The fundamental weakness in the report did not stop the White House from taking yet another unwarranted and unseemly victory lap over the inflation fight.

As per usual, the tweet was basically wrong. Little if any progress is being made against consumer price inflation, unemployment is only low because those in the labor force officially don’t count, and the economy is not actually growing despite what the BEA pretends.

First and foremost, we must note that core consumer price inflation per the PCE index began declining after February 2022, before the Fed began raising the federal funds rate.

Since February of 2022, core consumer price inflation per the PCE has declined by 15.2%, and headline inflation per the PCE by 21.7%.

To achieve that much reduction in consumer price inflation the Federal Reserve has raised the federal funds rate over six thousand percent.

After the Fed raised the federal funds rate that much, treasury yields rose, but not in keeping with the magnitude shift of the federal funds rate. The yield on 1-Year Treasuries rose 583%, the yield on 2-Year Treasuries rose 340%, and the yield on 10-Year Treasuries rose 196%.

All this to achieve a 15% reduction in the Fed’s favorite inflation metric.

Nor is it clear how much more the Fed can hope to accomplish with future increases to the federal funds rate. Given the largely lateral movement within core consumer price inflation per the PCE, the empirical reality is that, barring a renewed surge in consumer price inflation, the core PCE index shows inflation somewhat below the market yields at long last.

If we look at corporate yields inflation is already significantly below the yield levels.

Only AAA-rated yields are currently below core consumer price inflation per the PCE.

This begs the question how much more will further increases to the federal funds rate genuinely accomplish in terms of reducing consumer price inflation, as opposed to merely holding the line at the present level and allowing the markets to resolve what the equilibrium interest rate should be.

This question takes on even greater relevance when we consider that corporate interest rates, like treasury yields, began rising before the Fed began its process of raising the federal funds rate.

The narrative that puts the Fed in the driver’s seat on interest rates has always been substantially challenged by the facts on the ground.

This much is certain: the February Personal Income and Outlays Report does little to bring any clarity to what the Fed ought to do next, given its interpretations of the data to date.

This much is also certain: the data on consumer price inflation as measured by the PCE index shows once again that personal incomes have been steadily losing ground to consumer price inflation. For the White House to boast about rising incomes is simply absurd, because it simply is not true.

Even by the questionable metric of “real” disposable income as measured by the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Federal Reserve, which restates nominal disposable income in terms of 2012 dollars, from January 2021 (the start of the current regime in the White House) to the present, aggregate real disposable income has declined by some $1.477 Trillion.

To put that in relative terms so as to better convey the true size of the decline, if we index personal income to January of 2021, we see that real disposable income as of February is 8.6% lower than in January of 2021.

Moreover, that is the optimistic view of real disposable income. Actual disposable income levels as reported also include a measure of personal savings—a figure the February report details as being a positive figure.

Personal outlays increased $40.7 billion in February (table 3). Personal saving was $915.8 billion in February and the personal saving rate—personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income—was 4.6 percent (table 1).

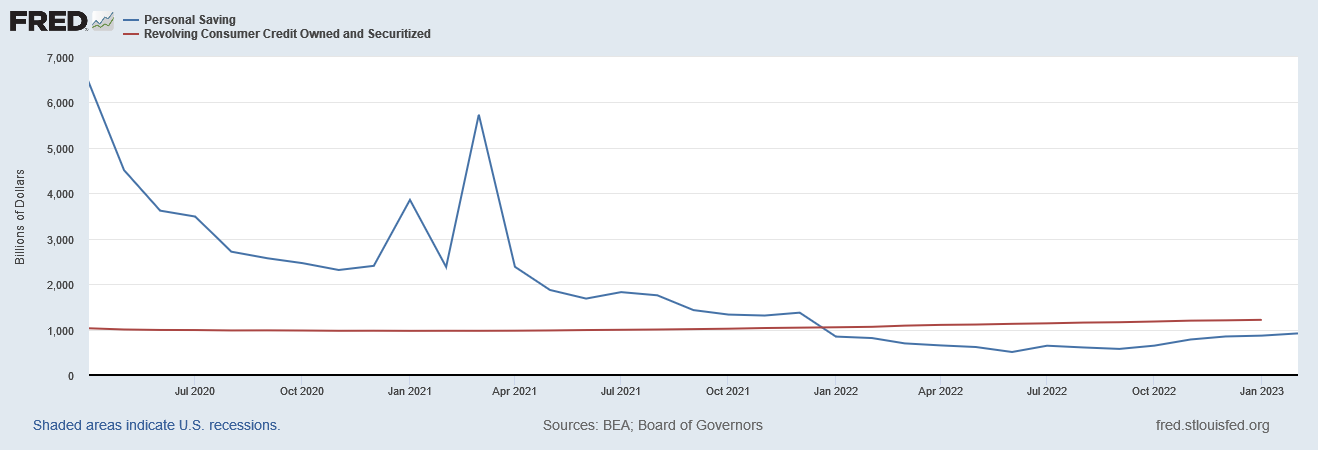

However, the personal saving rate runs up against the reality of rising revolving consumer debt, which exceeds personal saving by a substantial margin and has done so for several months.

Revolving credit growth more than offsets personal savings growth, which means that personal savings is effectively nonexistent—there can be no savings when people are getting deeper into debt by definition.

“Real” personal savings arguably is in deficit and has been throughout 2022 and the first couple of months of 2023.

That consumer price inflation is trending down is indisputably good news. It’s much better than inflation trending up.

Yet before the Federal Reserve or the economic illiterates in the White House take more unearned victory laps, we do well to consider the consequences of the Fed’s strategy for presumably bringing down consumer price inflation.

To the extent that the Fed’s strategy has influenced rising interest rates, they have unquestionably helped to catalyze the current banking and financial crisis.

That the crisis is largely the result of bankers forgetting the basic mathematics of interest rates, and failing to respond when the investment climate shifted towards rising interest rates, does not mitigate the Federal Reserve’s role in furthering that shift and thus exacerbating the crisis.

At a minimum, the Fed has earned a full measure of opprobrium for failing to articulate the likely consequences to the banking and financial sectors from the outset of their strategy, and thus use their bully pulpit to persuade bankers to address their sinking and now underwater fixed income portfolios before the size of the unrealized losses became too large. The Fed does not get a pass merely because after encouraging higher interest rates they stood on the beach and watched the bankers starting to drown.

Is helping to create this banking crisis more than offset by a ~15% improvement in core consumer price inflation per the PCE Index since 2020? Is this banking crisis an acceptable price to pay for a 21% reduction in headline consumer price inflation per the PCE Index?

Will the potential commercial real estate debt default crisis that may begin unfolding this year among $450 Billion of maturing commercia real estate debt be a fair price to pay for a marginal reduction of consumer price inflation?

To my cynical eye, the question seems very much like asking if it is appropriate to burn down a house to eliminate one cockroach.

I would prefer to get rid of the cockroach and keep the house. But then I’m greedy that way.