Apparently, Most Bankers (And Others) Have Been Swimming Naked

This Latest Financial Crisis Is Just Plain Stupid

Warren Buffett is said to have once observed that “only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

The tide has gone out on the banking industry and it seems most bankers as well as their largest depositors have been swimming naked—and are now blaming the tide going out for their deshabille.

On Thursday, at the gentle and innocuous suggestion of the Administration (no doubt channeling Marlon Brando as Vito Corleone, making Jaime Dimon an “offer he couldn’t refuse”), Dimon and 11 of his Big Bank pals dipped into petty cash to deposit some $30 Billion in collapsing First Republic Bank, which was shedding share price like a tree in autumn and on the verge of needing a takeover a la Silicon Valley Bank.

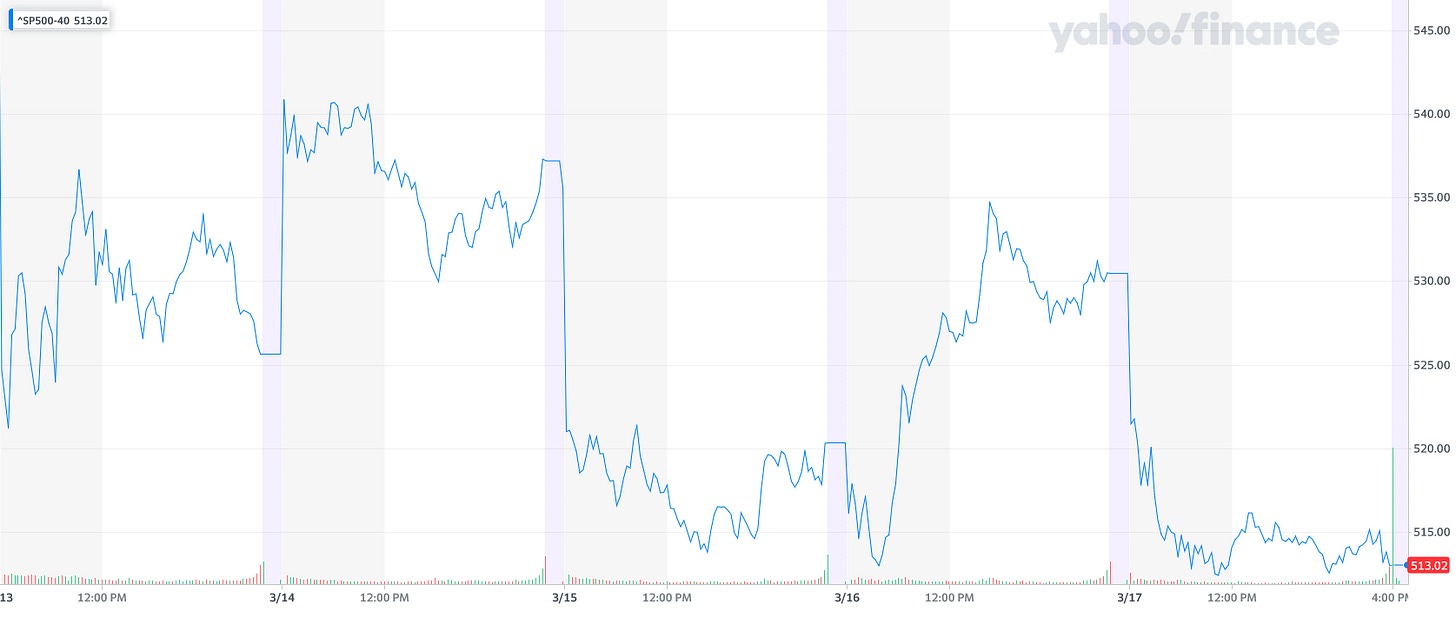

While the bank’s stock and Wall Street breathed a collective sigh of relief through the day’s closing, that relief turned out to be short lived. The stock resumed its downward plunge during after hours trading and continued after the opening bell on Friday.

Shares of First Republic Bank fell 25% Friday, erasing gains that followed a $30 billion rescue rolled out by the biggest U.S. banks.

First Republic is on track for its largest weekly drop on record and lowest close since 2011. The bank’s stock has lost more than two-thirds of its value over the past week.

Although the new deposits arguably gave First Republic a 120-day lease on life, after mulling it over, investors decided that wasn’t all that impressive.

For now, First Republic at least as a new 120-day lease on life. Whether that will be sufficient to bring anxiety levels in the US banking sector down to a level resembling “normalcy” remains to be seen.

We now know that the anxiety levels have moved up rather than down after the bailout.

Friday turned out to be another bloodbath for the banking sector. Not only was First Republic down hard on the week…

…but fellow regional banks PacWest BancCorp and Western Alliance were likewise succumbing to gravity.

In general, the entire banking sector shed value, with the S&P 500 Financials cratering, despite staging a recovery after the First Republic bailout was announced.

Nor was the carnage confined to the United States. Swiss banking giant Credit Suisse, which has also been on the ropes, continued to decline in share price even after a backstop from the Swiss National Bank cleared the way for the ECB to proceed with a surprise 50bps rate hike on Thursday.

Taking a page from the FDIC’s playbook over SVB, the Swiss National Bank and their financial regulator FinMa issued a joint statement pledging support for the beleagured Swiss banking giant, including liquidity support if need be.

Swiss regulators said Credit Suisse (CSGN.S) can access liquidity from the central bank if needed, racing to assuage fears around the lender after it led a rout in European bank shares on Wednesday.

In a joint statement, the Swiss financial regulator FINMA and the nation's central bank said that Credit Suisse "meets the capital and liquidity requirements imposed on systemically important banks."

This show of support apparently cleared the way for the ECB to proceed with the 50bps rate hike, its sixth in a row.

Investors were as unimpressed by the Swiss National Bank as they were by Dimon’s Eleven, as Credit Suisse stock continued to fall in after-hours trading.

The Swiss backstop, much like First Republic’s bailout, is being seen as little more than a stop-gap measure that does not address the core problems of the respective banks.

The rescue deal offered First Republic a “temporary lifeline,” KBW analyst Christopher McGratty wrote in a research note.

“The significance of these shifts in the balance sheet—along with an announced dividend suspension—paint a grim outlook for both the company and shareholders,” Mr. McGratty wrote.

To be blunt, Wall Street is correct. The bailouts and the backstops don’t rectify the actual problems endangering banks seemingly everywhere. All they do—all they can do—is buy beleaguered banks time to resolve the problems they have been facing for a year at least (arguably longer). If the banks do not resolve those issues, in time they will be right back at this same juncture, jonesing for liquidity.

In a post-mortem of Goldman Sachs’ failed attempt to rescue SVB, the Wall Street Journal skirted around the obvious: the banks screwed themselves bigly.

SVB’s problem was mechanical: Banks make profits by earning more from putting money to work than they pay depositors to keep it with them. But SVB was paying up to stop depositors from leaving, and it was stuck earning a pittance on low-risk bonds bought in low-rate times.

An earlier article in the WSJ laid the blame squarely at the banks’ feet.

The rest of the banking system is on edge. The episode has exposed a new set of vulnerabilities for the financial system. Bankers that grew up in the easy-money era following the 2008 crisis failed to ready themselves for rates to rise again. And when rates went up, they forgot the playbook.

Let us not forget something extremely obvious: when interest rates rise, legacy debt security portfolios lose value, as their yields sink relative to market rates.

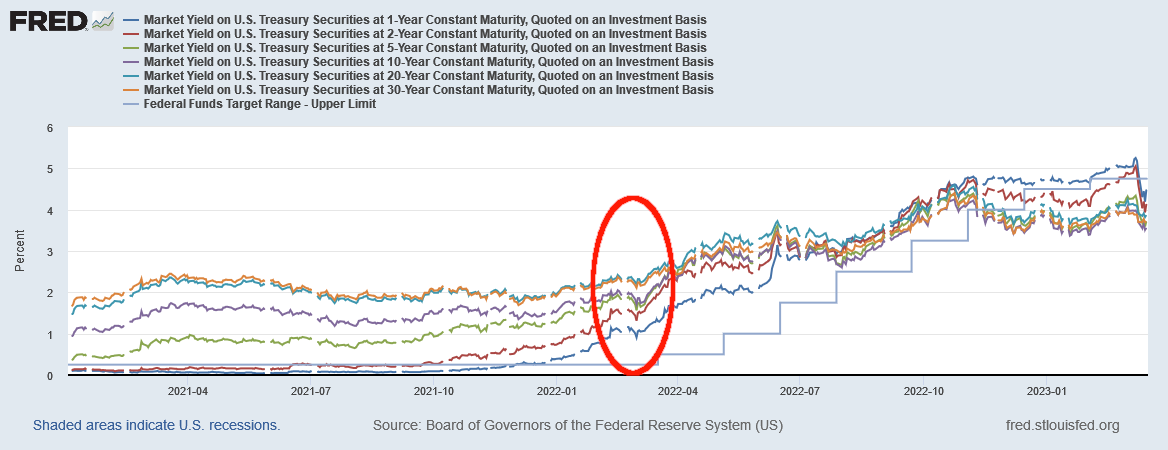

Yet let us also not forget something equally relevant. Interest rates began rising in 2021, months before the Federal Reserve first increased the federal funds rate in March of last year.

Treasury yields had risen by around a percentage point at the time Powell raised the federal funds rate last March.

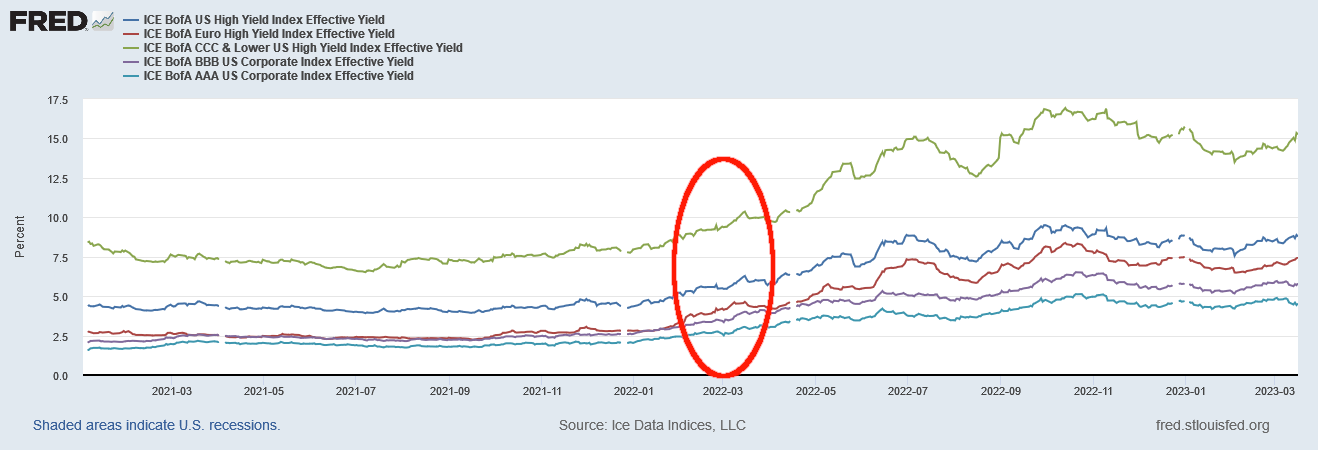

Interest on corporate debt had also begun to move up.

Mortgage rates had also begun their steady climb towards a 7% peak.

Remember, rising interest rates automatically decrease the value of legacy debt security holdings—not only reducing the value of the portfolio (through a ledger entry involving Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (or Loss)), but also making them that much more difficult to sell in order to cover bank deposits.

Across the board, interest rates for the most popular debt securities began rising due to indigenous market forces months before the Federal Reserve issued their first increase to the federal funds rate. As those interest rates went up, the value of bank portfolios of debt securities went down.

By the time the Federal Reserve announced their first rate hike, banks’ securities investments were already well on their way to being underwater.

How underwater?

The 10-Year Treasury yield on January 4, 2021, was 0.93%. For every $100 invested in 10 Year Treasury notes, the holder earned $0.93 in interest each year.

By March 16, 2022, the day before the federal funds rate rose by 25 bps, the 10-Year Treasury yield was 2.19%. At a yield of 2.19%, to earn $0.93 in interest one only needs to invest $42.47.

That was how much an investment in 10-Year Treasuries would have fallen in value between January 4, 2021, and March 16, 2022—before the Federal Reserve boosted the federal funds rate by so much as a single basis point.

This simple math exercise apparently eluded every top level banker at almost every US (and European, apparently) bank for all of 2021.

Nor can bankers claim to have been blindsided by the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes.

In the first place, it has now been a year since that first rate hike was instituted, and it has only been in the past couple of weeks the liquidity crisis has boiled over. Even if the Fed had sprung that first rate hike on Wall Street unannounced, bankers have had from then until now to figure out how to digest what were about to be rapidly declining holdings in debt securities.

Yet the bankers had more than the past year to figure that out. The Federal Reserve was openly contemplating rate hikes as early as June of 2021.

As expected, the policymaking Federal Open Market Committee unanimously left its benchmark short-term borrowing rate anchored near zero. But officials indicated that rate hikes could come as soon as 2023, after saying in March that it saw no increases until at least 2024. The so-called dot plot of individual member expectations pointed to two hikes in 2023.

By September of 2021, the FOMC had brought forward its timetable for raising interest rates to 2022.

Half of U.S. Federal Reserve policymakers now expect to start raising interest rates next year and think borrowing costs should increase to at least 1% by the end of 2023, reflecting a growing consensus that gradually tighter policy will be needed to keep inflation in check.

On September 22, 2021, when the FOMC made this announcement, the yield on the 10-Year Treasury was 1.41% (making that January $100 investment worth about $65.96).

Bankers were already confronted with rising interest for very close to a year before the Fed made its first rate hike—and yet a year after that first hike those same bankers are strapped for cash because they got “stuck” with low-yield assets on the books back in 2021? Despite having very close to two years to figure out a way to get “un-stuck”?

It is perhaps not so surprising then, that investors other than bankers take no comfort in First Republic’s 120-day reprieve from collapse and FDIC takeover. If First Republic couldn’t figure out how to avoid this mess with 720 days of advance notice, how much could the brain trust at the bank possibly accomplish in a mere 120 days?

By the same token, the blatherings of some “experts” putting all the blame on Fed Chairman Jay Powell’s pointed head are equally wide of the mark. While Economist Joseph Stiglitz is quite right to call Powell’s rate hike's “callous” in their impact on working folk, the impact of that on the present situation is not significant to the current crisis.

Now, as a result of Powell’s callous – and totally unnecessary – advocacy of pain, we have a new set of victims, and America’s most dynamic sector and region will be put on hold. Silicon Valley’s start-up entrepreneurs, often young, thought the government was doing its job, so they focused on innovation, not on checking their bank’s balance sheet daily – which in any case they couldn’t have done. (Full disclosure: my daughter, the CEO of an education startup, is one of those dynamic entrepreneurs.)

Whether or not the rate hikes are necessary is indeed a debating point (and I have pointed out more than once that the rate hikes were not having the impact on consumer price inflation that was being sought).

What is not a debating point is that the Federal Reserve’s strategy from the outset has been to inflict a recession, complete with rising unemployment, on the economy in order to bring inflation down. We know this is not a debating point because Jay Powell himself said so explicitly last August at Jackson Hole.

With his misunderstanding and mis-statement of the current state of the economy well in hand, Powell made it quite clear how he sees the Fed’s mandate: drag supply and demand back into equilibrium kicking and screaming if need be.

It is also true, in my view, that the current high inflation in the United States is the product of strong demand and constrained supply, and that the Fed's tools work principally on aggregate demand. None of this diminishes the Federal Reserve's responsibility to carry out our assigned task of achieving price stability. There is clearly a job to do in moderating demand to better align with supply. We are committed to doing that job.

Imagine that! When demand outpaces supply prices go up! Thank you, Captain Obvious!

The last part of that sentence, about the Fed’s “tools” (read, “rate hikes”) working “principally on aggregate demand”, should send chills down every consumer’s spine. Powell sees inflation as too much demand and too little supply (notionally correct, by the way), and sees the solution to too much demand as a simple matter of eliminating the demand.

For the unpardonable sin of consumers wanting to buy things, Jay Powell intends to raise interest rates until consumers are no longer able to buy things. “Demand destruction” is what will save the economy…although it won’t do much for consumers in the short run.

However, as outrageous as the Fed’s callousness is, it has zero bearing on the current crisis, which is not that people are suddenly being thrown out of work, but that bankers forgot to unload their debt securities portfolios before the rate-driven losses became too painful to consider. Stiglitz is giving the bankers a pass they do not deserve, and sparing them the contempt and opprobrium they do deserve.

There are many reasons to critize Powell for his rate hike strategy—the chief one being that it hasn’t worked, and that deliberately causing a recession is sucky economic policy on a good day coming in a close second. That Wall Street is now “broken” isn’t one of them. Wall Street has been tantruming for months over interest rates rather than doing a little adulting and resolving their balance sheets.

Nor are the depositors at failed Silicon Valley Bank without a measure of responsibility here. SVB catered primarily to venture capital firms and startups, all of whom just dropped their money in an uninsured SVB account and forgot about it until it wasn’t there. It was just easier to let SVB do all the heavy lifting managing their money.

SVB billed itself as a one-stop shop for tech visionaries — more than just a bank, a financial partner across loans, currency management, even personal mortgages. Its tactics to bundle client services were deemed aggressive by some, but it was hard to argue with the results: business with 44% of venture-backed technology and health-care companies that went public last year, and overall explosive growth during boom times.

In so doing, it created massive counterparty risk — a single point of failure that could imperil the sprawling financial ecosystem that backs America’s next big ideas.

SVB did not create that single point of failure. Silicon Valley’s tech startups and venture capitalists did, by not doing basic due diligence on the bank holding their money with zero insurance or other protection against the bank being stupid.

Nor is their lack of forethought and planning confined to their lack of cash management.

The reality is that Silicon Valley (and a fair number of other business sectors besides) has for years had a most unrealistic view of money and finance. Instead of viewing money as this sickly green stuff people use to pay their bills and buy a burger at Dairy Queen, they view money as a set of playing cards, with finance being a giant card game.

The world of finance is quite annoyed with Powell over his interest rate hikes right now, because an environment with rising interest rates ruins their game and scrambles all their finely tuned plans for sending startup companies into the public sphere via an Initial Public Offering of stock (IPO).

But a rebound won’t happen in earnest until Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell provides more certainty about the central bank’s path for rate hikes to curb inflation, said Steve Maletzky, head of equity capital markets at William Blair & Co.

“We need to see some plateauing or stabilization of interest rates, specifically the Fed’s policy around interest rates,” he said in an interview. “Once investors have more clarity on the trajectory of the yield curve, market volatility will subside and a friendlier deal pricing environment will return.”

How loopy is their thinking?

Consider: Fintech company Stripe just raised $6.5 Billion in fresh VC funding to deal with employees unexpected tax liabilities because their stock awards (to take effect when the company went public) had sat on the shelf for too long and were getting stale. (Full Disclosure: As mentioned yesterday, I use Stripe to process paid subscriptions to All Facts Matter.)

In other words, they raised $6.5 Billion to pay for not going public.

While it is commendable that Stripe did not want to stick its employees with a sudden tax bill, if the delay in their going public was an “unstable” interest rate environment, that environment has been unstable for going on two years. If an IPO was not going to happen then the equity awards and the associated tax issues were a known problem months if not over a year ago—and yet is only being addressed now.

It’s as if at the beginning of March someone at Stripe woke up and said “oh, yeah, our stock options are expiring, we should do something”.

That’s just not impressive business management.

Yes, interest rate rises devalue debt securities—and eventually destabilize derivative investments based on those securities. Yes, Powell’s rate hikes were always going to erode the fair market value of legacy investments in debt securities, which Wall Street has finally more or less admitted. Yes, future rate hikes will eventually destabilize the notional $1 quadrillion in derivative investments floating around the globe.

However, given that I have been writing about these things for months, by definition these risks have been known for months, if not longer.

If I, with nothing more than open source information and a Bachelor’s Degree in Accounting and Management, can see these risks coming down the road, all the really smart people on Wall Street, in venture capital firms, and in startups of one kind or another had to have seen those same risks—they have been that obvious.

Instead, everyone—Wall Street, the VC firms, the startups—simply ignored those risks (Powell knows the risks, but he’s made it plain he just doesn’t care). They ignored their most basic ethical duties to themselves—protecting their own assets—and are now crying “foul” that the risks they couldn’t be bothered to address have swum up to bite them in their dainty bits.

They chose to go swimming in the financial ocean stark naked and are now crying that they don’t have a towel to cover with after the tide ran out on them.

It has yet to occur to them that swimming naked without a towel nearby is just plain stupid—which also sums up how Wall Street handles its business of late.

I am just an electronic technician and computer programmer with no formal qualifications in any field. My efforts to understand large scale, international and corporate, finance, debt, fractional reserve banking, shadow banking, the tangled world of derivatives, CDSs, futures, stocks in general, exchange traded funds, central banks, currencies and their creation etc. has lead me to an ever-increasing number of questions which dwarfs what actual understanding I may have gained.

I believe a handful of people have a pretty good idea of how the parts of the whole system are related. They also presumably have a pretty good idea of what will happen to everything else when particular action is taken to affect one element of the whole system. However, this doesn't mean they can reliably predict what will happen with second to nth-order effects. Nor is there any reason to believe that many such people are in positions of responsibility and power, or that even if they were, they would act in a manner which is "responsible" regarding the health of the entire economy and society, however this might be defined.

Recent events suggest to me that the following is true, though I have never seen it stated so tersely as this,

Central bank currency emissions and/or government and corporate debt (turbocharged by the COVID-19 pandemic response) have lead to pervasive inflation. Central banks have only a few levers to pull in order to quell inflation.

The most obvious is raising interest rates in order to strangle personal, business and perhaps government expenditure by making it harder to obtain credit. This also has the effect of strangling banks, at least by way of reducing the real value of long-term bonds they keep as reserves.

Even if the banks don't need to make that loss of value physical, by selling said bonds, everyone knows the banks' reserves have lost real value as a result of rising interest rates. This makes banks, in general, not just less profitable (since when the bonds reach maturity they won't receive the real value they initially thought they would get, and will have to spend real currency at the time to buy the same real value of bonds to maintain their real level of reserves, but more prone to failure, this decline in reserves value also threatens their ability to pay depositors if more than a normal number of them withdraw their funds in a given time period.

Thus, rising interest rates makes the banks much more prone to bank runs - and one bank run naturally inspires runs on other banks in general, with spooked depositors not necessarily evaluating the particular risks of any one bank failing with respect to others - just the bank they happen to have their currency deposited in. In a panic, such evaluations are not likely to be particularly rational, so the contagion risk tends to affect all banks without regard to the prudence of their management.

As you and/or others have written, each attempt by the government or others to backstop one or a few banks does not relieve the fears of depositors in other banks, since everyone knows that such efforts can at best only help a few banks in total - and even then it is not at all guaranteed that such backstops could save the bank if there was a run on it.

Depositors, from individuals to corporations, view banks like a public service - they should never fail - AND they often choose to deposit their currency in banks which pay higher than average interest rates. This makes sense if there was no increased risk of not getting the currency back, but such banks generally take greater risks with their depositor's funds in order to maximise their profit, and to attract more funds with marginally higher deposit interest rates.

So banks are rewarded, in the short to medium turn, for taking risks - by the very depositors who may lose much of their deposit if the bank fails.

Meanwhile, depostitors and many other people tend to assume that the entire business and societal system depends on banks never failing, to the point of calling not just for better regulation, but for government support to support failing banks.

Here is the brief bit:

Central banks must strangle individual and business spending (and so activity in general, including the creation of employment and profits) in order to suppress the inflation they caused with their currency emissions and governments' addiction to deficits (this driven largely by the public's addiction to the idea of governments borrowing or printing currency in order to do whatever it is they want the government to do).

Such strangling - raising interest rates and soaking up currency rather than emitting it - also strangles banks. Yet while most people expect their bank to be protected by public expenditure, while they reward the riskiest banks by depositing currency in them.

This makes the most vulnerable banks (such as SVB, with an excessive proportion of its reserves in longer term government bonds) most likely to be picked off first by a bank run. Once someone has broken the ice on this potential popular contagion, all the other banks are at higher risk, and the chance of the runs snowballing rise, despite government efforts to damp down concerns.

Raising a country's interest rates tends to raise the value of its currency with respect to those of other currencies. This reduces inflation in that country by reducing the cost of imports, but it also weakens the whole country by making manufacturing industries (and tourism, and internationally saleable service industries) less competitive.

When the strangling destabilises a country's economy in a spectacular fashion - and bank failures, especially in just a few days are impossible to ignore and naturally inspire fear - the country's currency can fall, so increasing inflation (which, over many years, provides an increased chance that manufacturing, and so fundamental economic strength can be restored.

While inflation strangles everyone but the ultra-wealthy (who are, or should be, just as happy with a billion dollars as with two billion), central bank and government efforts to constrain it strangle everyone as well, and can make the house of cards economic system unravel rapidly by self-amplifying mechanisms such as bank runs.

Sorry, I can't really be brief at all.

It is easy to blame policy makers for these bank failures. They have certainly made a mess of things. But, as someone who is tangentially involved in the banking business, my humble opinion is that these failures are the direct result of incompetent management. Of course, every time you encounter one or more of these “dynamic” managers they are touted as the smartest people in the room.