Hiking interest rates apparently is not enough to slay the inflation dragon. At least, that appears to be the main takeaway from the January Consumer Price Index News Release.

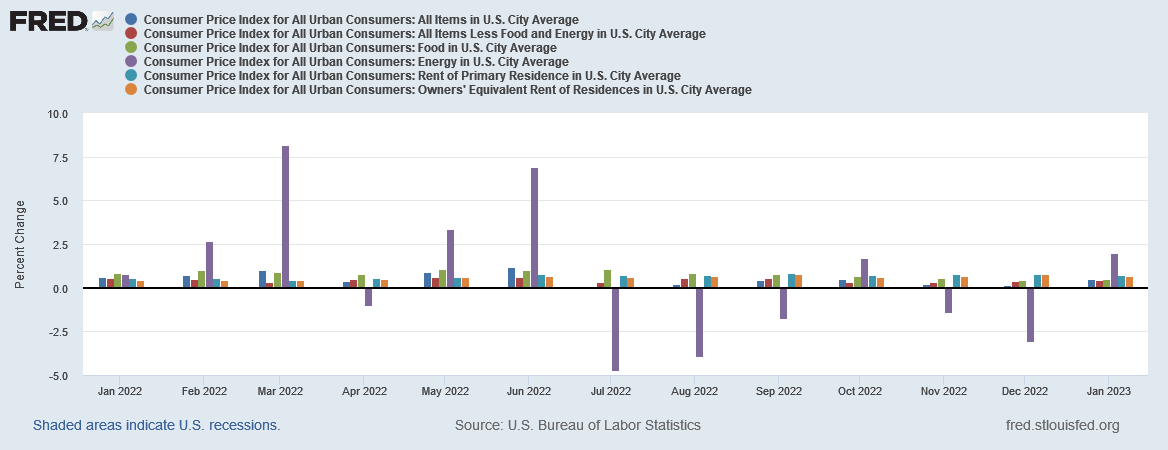

The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) rose 0.5 percent in January on a seasonallyadjusted basis, after increasing 0.1 percent in December, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the last 12 months, the all items index increased 6.4 percent before seasonal adjustment.

As I mentioned on Monday, some Wall Street analysts anticipated the inflation numbers would not be good, and this time the analysts got one right.

While year on year consumer price inflation still inched downward, the monthly rate rose by 0.4 percentage points from December.

That was just what happened to the headline number. Under the hood, as has been the norm for reports from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, lay more indications that the inflation picture is a worse than we are being told.

The first distressing data point to note is that monthly “core” inflation—CPI less food and energy—rose for the second month in a row.

Keep in mind that this is coming after the Fed has been raising interest rates since last March. Raising interest rates is supposed to force inflation down, not let it rise up even higher.

On an unadjusted basis, monthly food price inflation also rose significantly.

Unadjusted monthly energy price inflation also rose, after having been in the negative for the past two months.

Overall, within the unadjusted numbers, consumer price inflation is making a comeback, despite the Fed’s grand strategy of interest rate hikes. Clearly, this was not supposed to happen…yet it did.

However, we should not be too terribly surprised at this turn of events. The rise in the various elements of monthly consumer price inflation is merely a reflection of the degree to which the Federal Reserve simply does not have control over either inflation or its preferred weapon with which to combat inflation, interest rates—a situation I pointed out after the Fed’s latest hike in the Federal Funds rate.

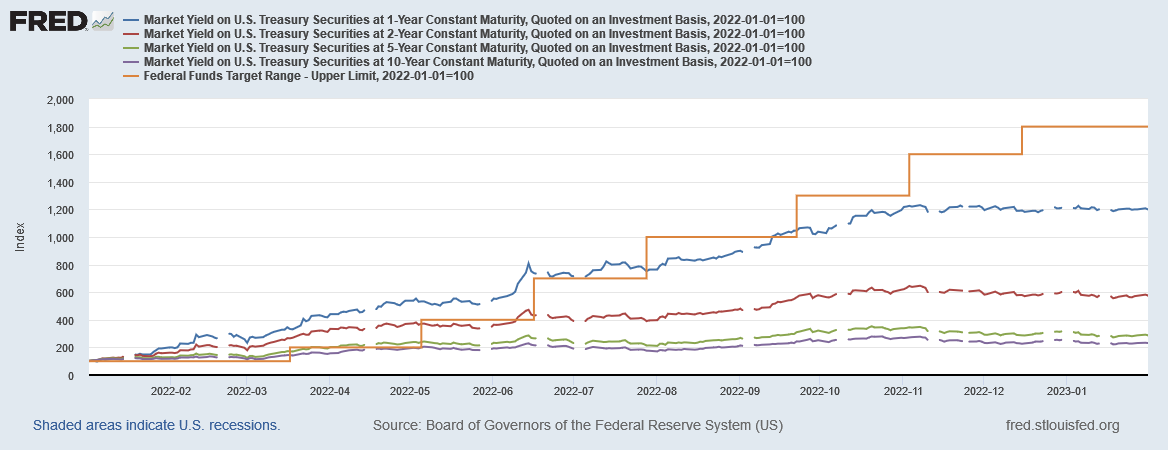

We can see the breakdown of the Fed’s influence when we look at the trajectory of Treasury yields as the Federal Funds rate has been increased. By late fall, the rate hikes in the Federal Funds rate was having little to no impact on Treasury yields across the lower end of the yield curve.

When we index both the Federal Funds rate and various Treasury yields to the beginning of last year, we can see that the Fed’s rate hikes in the Federal Funds Rate stopped having any appreciable influence over interest rates around the time of the November rate hike.

From November through January, Treasury yields largely plateaued, even though the Fed raised the Federal Funds rate 50bps in December.

With the Fed having lost control over interest rates, and interest rates being their only line of attack on consumer price inflation, the opening was left for supply side forces to begin pushing prices back up again—something I predicted last month.

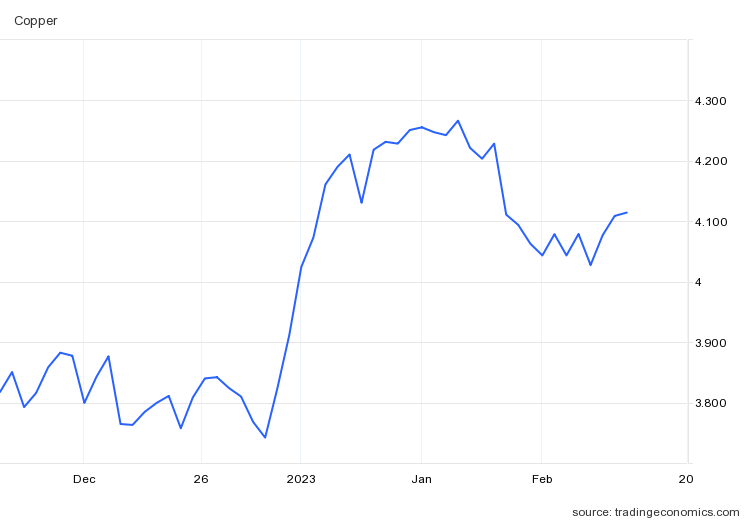

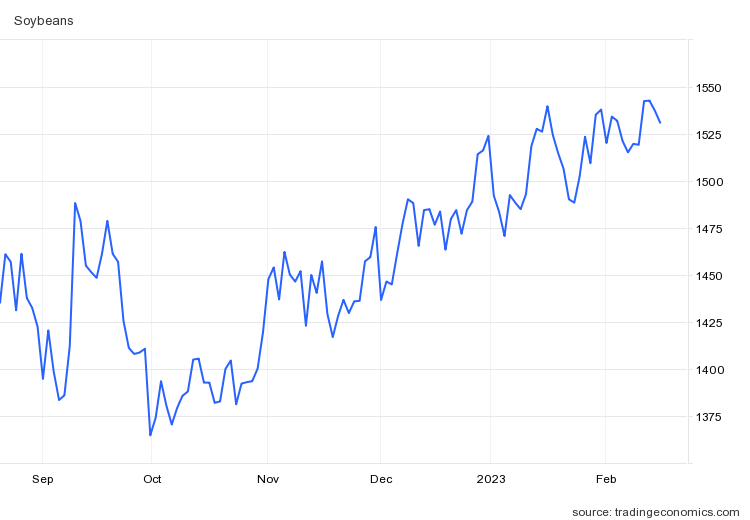

Commodities are the raw inputs of most manufacturing processes, and if the cost of inputs is going up, eventually so too will the price of outputs—and thus inflation will heat up.

As luck would have it, several commodity prices did trend up through January. Gasoline futures rose steadily until January 23.

Heating oil, while more volatile, showed the same trend and peaked on the same day.

Copper also rose from late December through late January.

Soybean futures have been rising for the past six months.

Corn futures began rising in December.

Nor should we forget that literally all fertilizer input prices rose to varying degrees throughout 2022.

It would be a dangerous extrapolation to argue that these various increases in commodity inputs and producer prices directly caused the particular monthly rises in consumer price inflation recorded for January. However, these same increases in commodity inputs and producer prices shows there have been (and still are) significant supply-side pressures which can combine to push consumer prices upward, irrespective of what the Federal Reserve does on interest rates. The technical term applied to this phenomenon is “cost-push inflation”1 and there is good evidence to support the hypothesis that we are seeing exactly that take place.

Cost-push inflation (also known as wage-push inflation) occurs when overall prices increase (inflation) due to increases in the cost of wages and raw materials. Higher costs of production can decrease the aggregate supply (the amount of total production) in the economy. Since the demand for goods hasn't changed, the price increases from production are passed onto consumers creating cost-push inflation.

The emergence of renewed cost-push inflation also tracks with a speculation I made at the end of December, that the Fed had reached the limit of what it could do on inflation, as the consumer price inflation that remained was of the “cost-push” variety, and thus largely immune to interest rate manipulations.

Arguably, this would also explain why Wall Street’s response to the inflation news did not include rises in Treasury yields sufficient to move either the 2-year or 10-year yields above the Federal Funds rate.

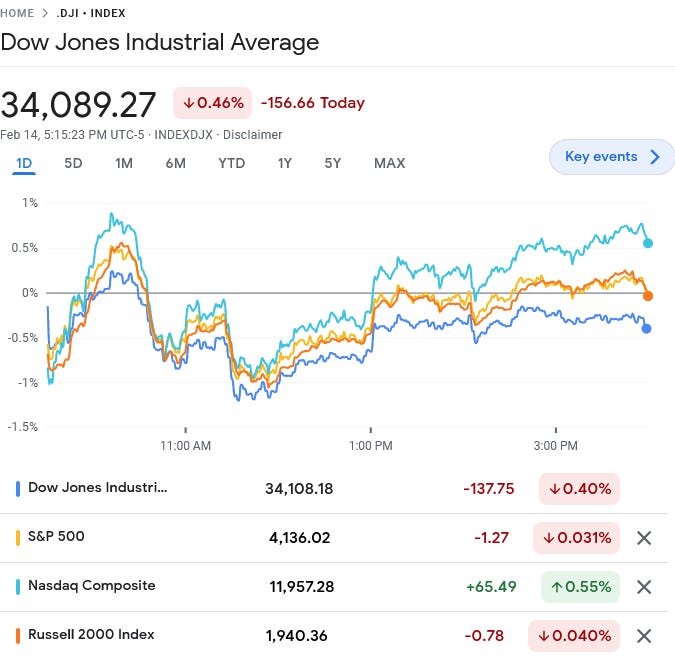

This would also explain why equity markets were more or less indifferent to the inflation news yesterday, with mixed results across the board.

In the Federal Reserve’s inflation-fighting narrative, everything can be managed through interest rate manipulations. To end the misery of rising prices, according to this narrative, the Fed merely has to keep pushing interest rates up, thereby squelching consumer demand, thus ending an inflationary impulse.

However, cost-push inflation does not depend on consumer demand. Rather, cost push inflation comes into the inflation picture from the supply side, and is reflective of either a transitory or permanent increase in the relative scarcity of various inputs. Raising interest rates under such circumstances will do nothing to relieve the underlying scarcity of raw materials.

Last month we saw that the Fed had lost control over interest rates. This month we are seeing that the Fed has little if any control left over inflation. The supply side is tightening up, and the Fed’s interest rate hikes are not going to make it looser again.

Kenton, W. Cost Push Inflation: When It Occurs, Definition, and Causes. 7 Mar. 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/costpushinflation.asp.

Don't really think the fed has a clue what to do. Not enough lifeboats on the Titanic. Linking as usual @https://nothingnewunderthesun2016.com/