Russia's Economy Is Contracting, Adding To The Global Economy's Woes

War In Ukraine Is Making The Global Outlook That Much Worse

A number of events and news reports emerged from the Russo-Ukrainian War this past week which invite a fresh look at the state of Russia’s economy, and possible ramifications for the global economy if Russia’s economy deteriorates.

The most notable news item is the report in the Associated Press that Russia is pulling troops back from positions near Kharkiv.

Russian Defense Ministry spokesman Igor Konashenkov said troops would be regrouped from the Balakliya and Izyum areas to the eastern Donetsk region. Izyum was a major base for Russian forces in the Kharkiv region, and earlier this week social media videos showed residents of Balakliya joyfully cheering as Ukrainian troops moved in.

What makes this item particularly noteworthy is the report in the Guardian just one day earlier of Russia reinforcing positions around Kharkiv.

Moscow is sending columns of military reinforcements to Ukraine’s Kharkiv region, according to reports in Russian media, after the first major Ukrainian counterattack since spring made big territorial gains this week.

This sudden reversal in Russia’s narrative of its own operations provides an interesting context for a remarkable report made at the beginning of the week that Russia was seeking to purchase artillery shells and rockets from North Korea.

Russia could be about to buy "literally millions" of artillery shells and rockets from old Cold-War ally North Korea, the White House said on Tuesday, calling this further evidence of Moscow's "desperation" amid supply shortages for its war in Ukraine.

We should note that Russian officials have denied this report first made by US intelligence services—which tells us nothing about the report’s veracity.

Yet these news items are of interest because, while they speak to military matters, they present a view of the Russian economy which suggests that it is doing far worse than some might believe, and that the available data should be viewed with an eye towards the “worst case” interpretation.

With Russia pulling back forces in a major theater of operations in Ukraine, if that much of the reporting is true, how much more is also true? And what does that portend not just for the future of the Russian economy, but for the global economy as well?

Can Russia’s Economy Support Russia’s War Effort?

It does not require a military genius to see that a pullback by Russia’s forces indicates an inability for Russia to supply those forces. The Russian retreat from Kharkiv thus becomes a tacit admission that Russia’s economy is not succeeding at supporting Russia’s war effort.

As I noted last month, the available economic data points to a Russian economy that is mired in contraction.

To be sure, Vladimir Putin argues—even boasts—otherwise. In addressing the Eastern Economic Forum last Wednesday, Putin asserted that Russia’s economy was surviving the sanctions imposed by the EU and NATO after the invasion of Ukraine.

“I would like to note that we believe, both in the government and in the presidential administration, our experts believe that the peak, the most difficult period [for the country's economy], has passed. The situation is normalizing, and macroeconomic indicators speak of this,” Putin said.

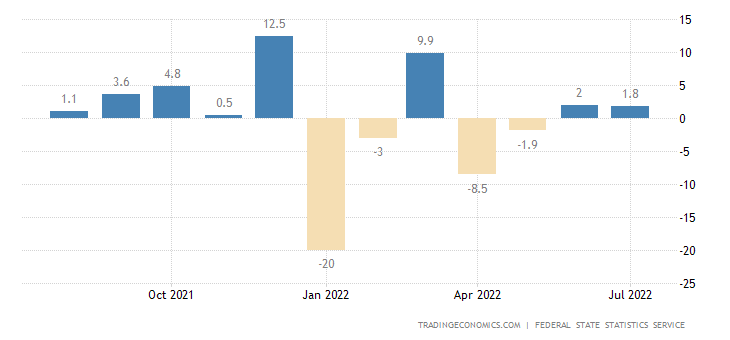

However, Russia’s own Rosstat, their official keeper of government metrics, would later report that the economy contracted in the second quarter by more than previously estimated—shrinking by 4.1% instead of the originally reported 4%—with economic declines happening across nearly all sectors:

Retail and wholesale sales together with repair work for vehicles showed in the second quarter the largest year-on-year contraction of 14.1% among other parts of gross domestic product.

The manufacturing sector shrank 4% and extraction of mineral resources fell 0.8%, wile the construction sector expanded 3.4%, Rosstat said.

The contraction in manufacturing is rather intriguing, as manufacturing arguably would include the production of war materiel. While the production of civilian consumer goods could even be expected to decline under the demands of the war effort, the production of munitions and military goods almost has to increase if Russian troops in Ukraine are to be sustained.

Curiously, Russia’s manufacturing woes may even predate the war, as industrial production fell off a cliff in January—before the war began—and has struggled to recover since.

In addition, Russian banks lost nearly $25 billion (₽1.5 trillion) during the first half of 2022, according to Russia’s central bank.

In January-June, the losses of the banking sector reached ₽1.5 trillion, the largest banks took the brunt, said Dmitry Tulin, First Deputy Chairman of the Central Bank. While the banks cost "little blood", he believes, they have a capital reserve of ₽7 trillion

This was the first loss for the Russian banking sector in seven years, and is quite the reversal from the ₽164 billion net profit the banking sector reported in January. While much of these losses stemmed from the financial ruptures due to sanctions, significant losses among Russia’s banks—and the accompanying reduction in banking capital—can only work against Russia looking to stimulate economic activity domestically, as lack of banking capital quickly translates into lack of loans and other forms of stimulus.

None of this points to a Russian economy able to sustain the war of attrition into which the invasion of Ukraine has devolved for Russia.

Oil Exports Are Confronted By Declining Prices Despite The War

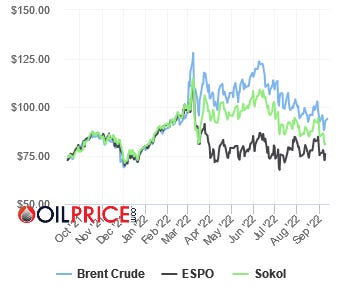

While Russia is still able to sell its oil abroad, the war has not boosted the price of oil globally—Brent crude is still trading at the same spot prices now as before the war began, while Russian oil is trading at significant discounts to the benchmark Brent price.

Russia may still be able to sell its oil, but it’s realizing far less revenue than it would have otherwise.

The discounted price for Russian oil is a primary reason why countries such as India are stepping up their purchases since the war’s start—they are taking natural advantage of the price cuts to lower their overall cost of energy.

The South Asian nation has ramped up imports of Russian oil this year, benefiting from discounted rates. According to the petroleum minister, Hardeep Singh Puri, India will continue to purchase Russian oil despite growing pressure from the West. He explained to CNBC this week that it’s a question of energy security and moral duty to the country’s citizens as India consumes around five million barrels of oil per day.

China has likewise increased its purchase of Russian oil, although the discounts mean Russia is gaining far less revenue than the increased quantities would normally indicate.

But while China is buying more oil, they are not selling more equipment and other finished goods—and Russian sources suggest there is little enthusiasm from China for doing so.

China is in no hurry to intensify its supplies to the Russian Federation. “It is not uncommon for Chinese banks to be extremely cautious about their clients from Russia,” Alexei Dakhnovsky, Trade Representative of the Russian Federation in the PRC, who spoke at the WEF, explained on Wednesday. “Understanding the origins of this approach, nevertheless, we are convinced that both Russia and China need to intensify the relevant work ... to work towards the creation of a cross-border payment mechanism that is not subject to hostile sanctions,” the trade representative said.

Given that China was already Russia’s major trade partner before the war, accounting for some 25% of Russian imports, the lack of additional imports from China suggests that goods normally sourced from the West are not being replaced, and even Russia’s central bank has acknowledged the need for Russian industry to adapt by becoming less dependent on imported goods and equipment.

An indirect confirmation of the fact that there is no acceleration in the supply of Chinese equipment to the Russian Federation comparable to the growth of Russian exports can also be the conclusions of analysts from the Central Bank’s Research and Forecasting Department from the study “What Trends Say” published on Wednesday: a gradual decline in the production of goods dependent on investment imports , which has decreased due to external restrictions, for Russia so far looks like a more realistic scenario than active import substitution.

What Happens If Russia Cuts Off Oil And Natural Gas Exports?

Russian oil revenues from China are almost certainly helping to sustain the energy sector in the face of NATO sanctions, but Russia has a significant challenge there going forward: China’s imports are shrinking overall, and China is buying less oil.

Inbound shipments rose just 0.3% in August from 2.3% in the month prior, well below a forecast 1.1% increase. Both imports and exports grew at their slowest pace in four months.

China's imports of crude oil, iron ore and soybeans all fell, as the strict COVID curbs and extreme heat disrupted domestic output.

With oil imports into China down nearly 10%, Russia may already be realizing all the revenue cushion from China that it can hope to get.

This does not augur well for Russia’s economy if Putin follows through on a threat to cease all exports of Russian energy to Europe if a proposed price cap comes into play in the sanctions regime.

"We will not supply gas, oil, coal, heating oil - we will not supply anything," Putin said.

"We would only have one thing left to do: as in the famous Russian fairy tale, we would sentence the wolf's tail to be frozen."

Russia is the world's second largest oil exporter after Saudi Arabia, the world's top natural gas and wheat exporter. Europe usually imports about 40% of its gas and 30% of its oil from Russia.

If Russia loses Europe as an energy customer, China is not likely to pick up the slack, especially if the price for oil increases should Russia impose an energy embargo on Europe.

Thus, even if Russia’s economy is managing to stave off a complete collapse, much to the chagrin of NATO, far from poised to recover from the sanctions, the Russian economy may be about to decline further.

A Perfect Storm Of Contractions

Whether Russia is “winning” or is likely to win its war with Ukraine is a speculation I do not care to make. However, the reality on the ground right now is that Russia is retreating from Kharkiv. While one battlefield success does not turn the tide of war in favor of Ukraine, it does highlight the possibility that Russia could potentially lose the war.

Win or lose, however, Russia’s war in Ukraine is furthering the breakdown of globalization and a near complete decoupling of the economic ties among nations.

China is purchasing less oil even as it buys more of it from Russia.

Europe is set to go without Russian energy sources altogether—wisely or unwisely—suggesting that their weaning off Russian energy will be permanent (certainly Europe’s leaders would like that to be the case). With the economic dislocations headed Europe’s way this winter from the disruption of energy supplies, Europe’s ability to purchase Russian energy resources is facing serious diminution regardless of the political situation.

Taken together, Russia is likely looking at a diminished global market for its energy resources.

Russia is already facing losses of imports essential to its own industry, and it will have to adapt to survive wholly on domestic manufacture, especially if China’s economy continues on its own path of decline. That we have reports of Russia seeking to buy even basic munitions from North Korea suggests that it is ill prepared to execute such a transition.

While Russia’s economy lacks the size and heft of China’s, its status as the world’s leading energy exporter makes it rather more consequential to the world economy than its size alone might suggest. Disruptions to domestic manufacturing coupled with losses of oil and gas revenues would bode poorly for energy production, as the availability of needed equipment and maintenance items for the oil and gas fields themselves would be under significant duress for the foreseeable future.

Russia may be forced to curtail oil production now (or, rather, soon), with no certainty it will be easily able to ramp back up later. The world could very well be facing a long-term structural decline in the availability of Russian oil and gas, which in turn diminishes prospects for future global economic growth.

That Russia is retreating from Kharkiv means that, win or lose, the war in Ukraine will not be ending any time soon, and so these Russia-centric economic dislocations will only continue.

The reverberations of contractions in the Russian economy across the wider global economy are adding to the perfect storm of global contraction. However bad the global economy is now, however mired in recession the Russian economy is now, things are poised to get considerably worse.