One reason the Fed feels it is justified in its obessive pursuit of demand and labor destruction as a means to corral consumer price inflation is the existence of a consumer “nest egg” of “excess savings”—a presumed pile of cash American consumers acquired during the 2020 pandemic lockdowns which has been acting as a buffer, shielding many Americans from the full pain of rising consumer price inflation.

Consumers built up unprecedented savings buffers during the Covid-19 pandemic, thanks to government stimulus and fewer opportunities to spend. The extra cash helped households pay down debt, buy goods like new appliances and furniture during lockdowns and take vacations once restrictions lifted. It gave businesses leeway to raise prices and hire more workers to meet stronger demand.

By some estimates, this pile of cash currently amounts to some $1.7 trillion, enough to fuel consumption despite rampant inflation for another 9 to 12 months. According to Federal Reserve economists1, this represents about 74% of the total stock of so-called “excess savings” built up in 2020 and 2021, which has been calculated to be some $2.3 trillion.

Over the pandemic, historic levels of government transfers boosted household income while household spending was severely curtailed by social distancing. This led the personal saving rate to soar (Figure 1), and we estimate that U.S. households accumulated about $2.3 trillion in savings in 2020 and through the summer of 2021, above and beyond what they would have saved if income and spending components had grown at recent, pre-pandemic trends. Since late last year, households have decumulated about one-quarter of these excess savings, as the saving rate has dropped below its pre-pandemic trend.

There is just one problem with this “excess savings” construct. It never really existed, and certainly not as the broad-based phenomenon applicable across the entire American population the Federal Reserve posits it to be.

To understand the problem with this “excess savings” construct, we must begin with the personal savings rate—defined as the ratio of personal savings to disposable personal income (DPI)—as projected by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. During the 2020 lockdowns and their immediate aftermath, personal savings in this country increased dramatically.

It is not uncommon for savings to increase during and immediately after a recession, owing to a general decline in consumption during a period of economic contraction—by virtue of simple math, whatever DPI is not spent on consumption must become personal saving. A review of the historical data on personal savings in this country confirms this.

Prior to the 1980 Volcker Recessions, personal savings rates moved largely independently of both interest rates and consumer price inflation.

After the Volcker Recessions, as interest rates and consumer price inflation declined, so did personal savings, and in the years prior to the 2020 pandemic lockdowns, interest rates, consumer price inflation, and personal savings had largely stabilized at relatively low percentages.

This was the savings apple cart that the pandemic lockdowns upset. With the US economy fundamentally shut down in early 2020, opportunities for consumption greatly diminished, and personal savings skyrocketed as a result.

This notion poses no great challenge in either fact or logic, until one drills further into the data, to understand how this increase in savings—what the Fed terms “excess savings”, as it represents savings that would not have occurred but for the pandemic lockdowns—comes to be.

As is always the case in times of economic turmoil, the savings arose from different sources depending on which earnings bracket one wishes to examine. In the bottom income quartile, the excess savings occured primarily because of fiscal support—the variety of government transfer payments made to sustain households during the dislocations of the lockdowns. At the other end of the income scale, the excess savings occured primarily due to reduced consumption.

However, an important consideration arises because of this disparity of origin. As the chart shows—as the Fed’s own data shows—in the lower income brackets, not only was the excess savings largely the result of government largesse, it was largely offset by continued consumption. Significant reduction in consumption does not occur until one rises to the third quartile, and only predominates in the top quartile.

Because of the offsets to the primary contributors to excess savings in each quartile, the total amount of savings in each quartile is different, with the top quartile accumulating the most excess savings. Of the current $1.7 trillion stock of excess savings, $825 billion—48%—is held by the top income quartile, and only $92 billion—5%—is held by the bottom income quartile.

In other words, most American consumers had little to no “excess savings” as a result of the pandemic lockdowns. The Fed’s own data also makes this point abundantly clear.

From the beginning of the pandemic lockdowns, the upper income quartiles have been the primary beneficiaries, accumulating the lion’s share of “excess savings”.

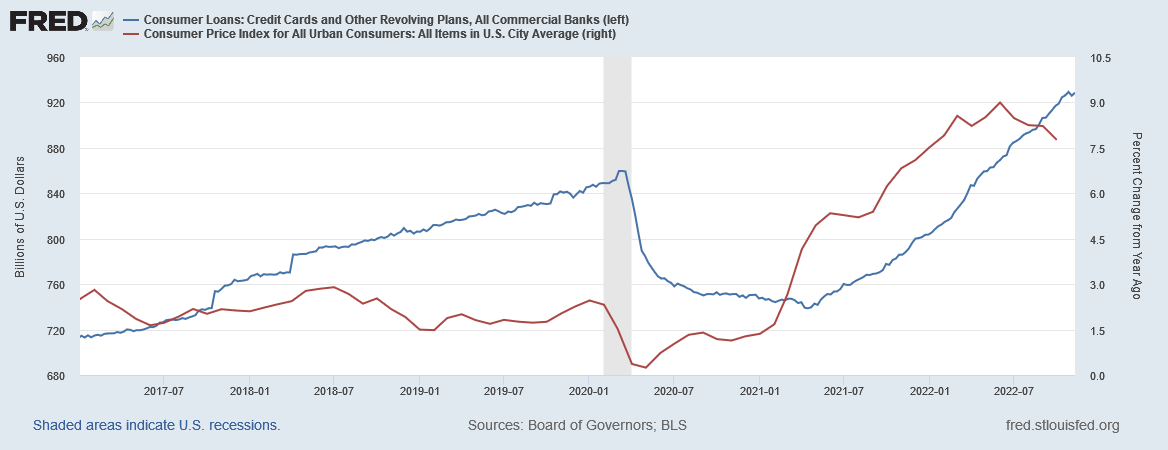

This reality shows up in another set of data as well—credit card balances. Post-pandemic, as inflation has accelerated in this country, so has credit card debt, with the two rising almost in tandem.

When one considers the composition of the so-called “excess savings”, the rise in credit card debt is unsurprising. The lower income brackets, with relatively little in the way of excess savings, exhausted their savings fairly quickly, and have been relying increasingly on credit card debt to support consumption.

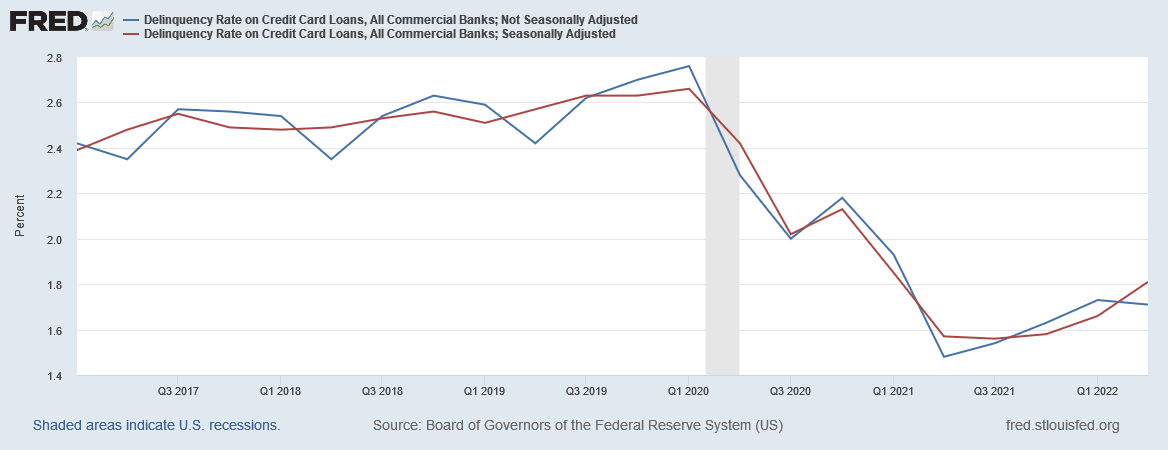

This shows up again in rising credit card delinquencies since mid-2021.

Although the Fed believes “excess savings” to be a primary driver of consumer price inflation, the empirical reality is that, for most American consumers, such “excess savings” were marginal at best, and have been long since exhausted, with debt taking its place. This debt is becoming increasingly more expensive as the Fed pushes interest rates up, pushing credit card interest rates up as well.

With housing, transportation, and food comprising over 60% of consumer purchases in 2021, the error of presuming the average consumer has a stock of excess savings to support his or her consumption takes on an existential aspect.

The rise in credit card debt amid this distribution of personal expenditures means that more and more consumers are truly living paycheck to paycheck, with little or no savings to sustain them, instead relying on credit card debt.

Pushing the cost of credit card debt up by raising interest rates, in addition to being largely ineffective thus far against consumer price inflation, means that the costs of the Fed’s inflation strategy is borne by the same income brackets that bear the greatest burdens from consumer price inflation. It is far from an exaggeration to say that the Fed’s inflation strategy targets the poor to benefit the wealthy.

Indeed, this is what Fed Chair Jay Powell proclaimed as the Fed’s strategy at Jackson Hole back in August.

It is also true, in my view, that the current high inflation in the United States is the product of strong demand and constrained supply, and that the Fed's tools work principally on aggregate demand. None of this diminishes the Federal Reserve's responsibility to carry out our assigned task of achieving price stability. There is clearly a job to do in moderating demand to better align with supply. We are committed to doing that job.

The Federal Reserve is targeting a stock of savings that, for most consumers, never really existed, and where it did exist has been exhausted already for months. Meanwhile, those consumers who still have significant “excess savings” are being spared the Fed’s anti-inflationary wrath.

This is a double tragedy, as in addition to being largely ineffective against inflation, such a strategy is the epitome of an economic and political double standard, with the wealthy being treated far differently than the poor. Thus the Fed’s strategy promises much pain with little to no gain.

Aladangady, Aditya, David Cho, Laura Feiveson, and Eugenio Pinto (2022). "Excess Savings during the COVID-19 Pandemic," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, October 21, 2022, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3223.

Any savings consumers might have had probably went to paying bills due to the fact they couldn't go to work because where they worked at was locked down or did not have a customer base. Most small businesses had to deal with limited capacities. When restaurants, bars, hotels, etc. have to reduce capacities by 75% then their workforce is reduced as much as well. Powell and the other banksters are idiots, they know all this!!!!! Can't wait to hear their next line of "BS"!!! Linking tomorrow as usual @ https://nothingnewunderthesun2016.com

“Excess saving” is just another straw man that “caused” inflation. The obsession with blaming inflation on anything but the real causes (i.e., fed and government’s own policies) is sickening. It allows the real causes of inflation to continue unabated.