The PBOC Is Fighting Deflation...By Tightening?

China's Latest Money Moves Highlight The Limits Of Monetary Policy

Beijing has a serious economic problem: it’s usual avenues of economic stimulus are all effectively blocked, and at a time when China desperately needs economic stimulus.

The latest evidence of China’s economic Catch-22 comes via the recent decision by the People’s Bank of China to shrink the money supply—usually the exact opposite of what central banks do when an economy is in deflation.

China drained cash from the banking system with a medium-term liquidity tool for the first time since November 2022, extending its cautious approach of using monetary policy to boost growth and showing its willingness to support the yuan.

The People’s Bank of China withdrew 94 billion yuan ($13 billion) of cash from the banking system on a net basis to avoid excessive liquidity, while it kept the rate on its one-year policy loans steady at 2.5% on Friday. Earlier today, Beijing set its daily reference rate for the yuan, with the largest strong bias to the Bloomberg-survey estimate since November.

The rate decision will likely disappoint investors and economists who anticipate more stimulus is needed for the government to achieve its ambitious economic growth target of around 5% for this year. It also underscores the PBOC’s limited scope in further easing monetary policy — given a wide US-China interest rate differential — before the Federal Reserve’s policy pivot.

There is a perverse irony in the reality that the PBOC, despite being at the helm of a centrally managed economy, literally cannot at this juncture cut interest rates or goose the money supply as much as the data would otherwise suggest, because any such move would likely trigger a potentially catastrophic yuan devaluation.

“We expect there is limited room for PBOC policy easing before global central banks start to cut rates, as yuan stability remains a policy objective and further widening the interest rate spread with a rate cut would add to depreciation pressure,” said Lynn Song, Chief Economist for Greater China at ING. The central bank may reduce reserve-requirement ratio in coming months before slashing the rates on MLF, he said.

Beijing is stuck in a policy straitjacket, because the looser monetary policy economic conditions suggest is needed would be crippling to the Yuan, while maintaining the yuan even at present levels against the dollar means the economy is left to languish.

Heads Beijing loses. Tails Beijing does not win.

We can see the Catch-22 in which Beijing is trapped just in the rather schizophrenic policy decisions that are being made, such as lowering some interest rates while standing pat on others.

China's one-year loan prime rate (LPR), a market-based benchmark lending rate, was 3.45 percent on Wednesday, unchanged from the previous month.

The over-five-year LPR, on which many lenders base their mortgage rates, also held steady from the previous reading of 3.95 percent, according to the National Interbank Funding Center.

Last month, China cut the over-five-year rate by 25 basis points to 3.95 percent, the largest drop in recent years. The one-year rate remained unchanged in February.

A lower LPR is expected to shore up the credit and property markets, reduce the financial cost of businesses and individuals, and contribute to a steady economic recovery.

Beijing is attempting to have its cake and eat it too, lowering certain interest rates to incentivize longer term borrowing (mainly as a stimulus measure to slow the inexorable collapse of China’s property markets), while leaving other rates unchanged and thus providing no incentive at all for other types of credit and spending patterns.

A primary reason being attributed to these paradoxical policy choices is the need for the PBOC to respond to the policy decisions of the Federal Reserve.

China's central bank left a key policy rate unchanged while withdrawing cash from a medium-term policy loan operation on Friday, as authorities continued to prioritise currency stability amid uncertainty over the timing of expected Federal Reserve interest rate cuts.

The Fed's historic monetary tightening has bolstered the dollar and pressured the yuan over the past few years. Cutting rates before a move by the Fed or other major central banks would widen yield differentials, potentially putting more pressure on the local currency.

While China’s internal economy arguably makes a case for looser monetary policy, the need to defend the yuan against other currencies (and the dollar especially), calls for a more restrictive monetary policy and a smaller money supply, in order to support the yuan in forex markets.

Deflation is only going to be made worse by a smaller money supply, and yet the yuan demands that there be a smaller money supply. There is no way to reconcile the need to cure deflation with the need to defend the yuan when the two priorities are diametrically opposed as these are.

Thus we see in deflationary China a decline in the basic M0 money supply of CNY38.86 Billion in February.

We see a decline in the M1 money supply of CNY 2.83 Trillion.

That steep drop in the M1 money supply puts the M1 at just CNY 0.8 Billion more than in February of 2023. The PBOC wiped out an entire year of money supply growth in a single month, and at a time when deflationary shocks are already hitting the Chinese economy.

For the M2 money supply, there was an increase of “only” CNY 1.93 Trillion, vs a nearly CNY 6 Trillion increase in January.

These more restrictive money supply stances by the PBOC are in contrast to the bank’s reluctance to reduce the loan prime rate any further. While the PBOC was willing to make a substantial cut in the 5-year LPR last month, for the 1-year LPR the bank has stood firm since August of last year.

Thus the PBOC is been tolerating a measure of loosening while at the same time locking down a policy of overall tightening.

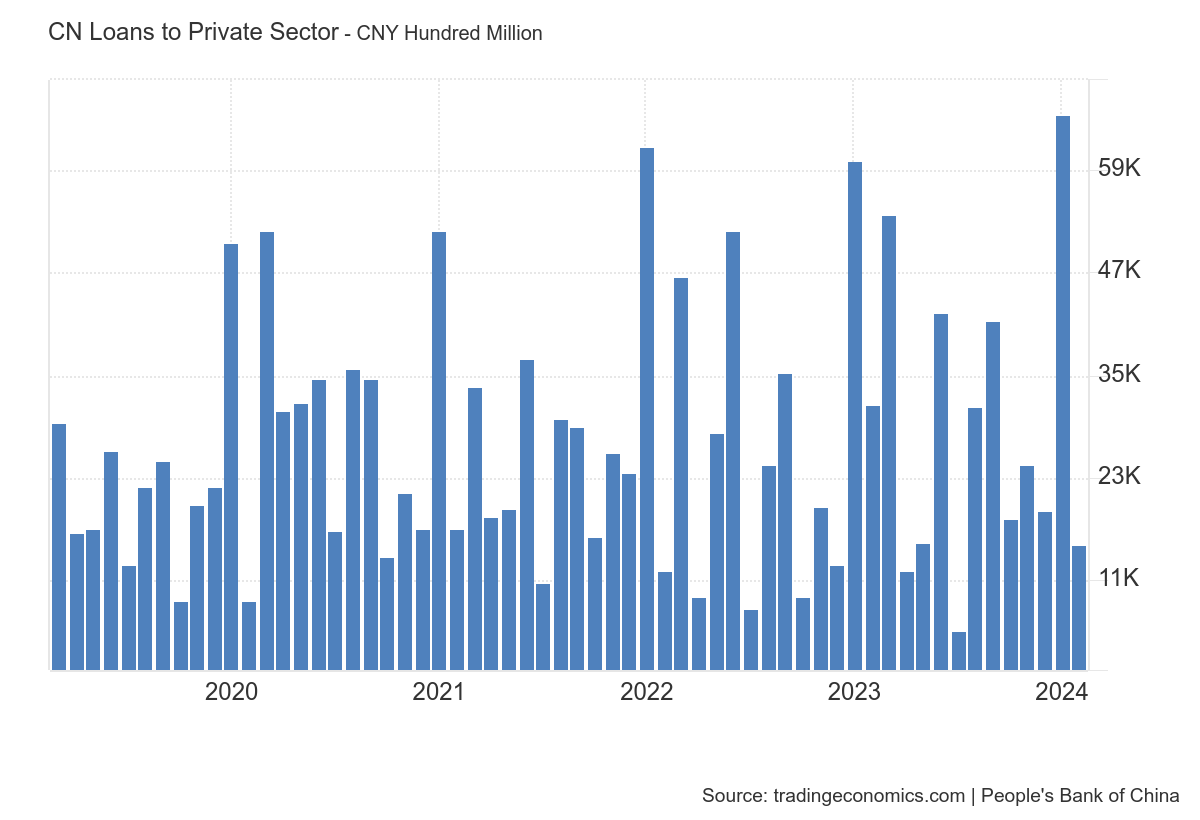

One possible consequence of the PBOC’s dichotomous moves is arguably a decrease in new yuan loan growth. In February new yuan loan growth printed at a level below that of February 2023.

While there is historically a significant drop off in new yuan loan growth between January and February in any given year, that this year’s drop off left new yuan loans printing below there they were a year ago means that corporate media is likely correct that this is a sign of the Chinese economy contracting even further.

The story is even more stark when one considers China’s level of total social financing, which posted an even steeper drop month on month than new yuan loan growth

While year on year loans to the private sector are still up significantly, February’s drop off compared to January’s stellar increase is a pretty dramatic and not very welcome turnaround.

Nor are Chinese equities particularly pleased with the latest policy announcements from the PBOC. Every index but Hong Kong’s Hang Seng posted a lost as the PBOC made its rate announcement yesterday.

Yet perhaps what is most concerning—or should be most concerning—for the Chinese economy is that the PBOC’s dramatic trimming of the M1 money supply in particular produced little more than yuan stability against the dollar in forex markets.

Why the stability of the yuan against the dollar would be a primary policy concern for the PBOC is easily seen from the historical prices for the yuan against the dollar. Throughout much of 2023, the yuan steadily lost value against the dollar, and the PBOC historically prides itself on keeping the yuan within relatively narrow trading bands most of the time. A weakening yuan is never something China is particularly pleased to have.

Yet the stability of the yuan in recent weeks against the dollar underscores the dilemma Beijing faces with its economic challenges. Were Beijing to unlease the massive levels of monetary and fiscal stimulus that reinvigorating the economy arguably needs, the yuan would crash through its previous low against the dollar, making a complete pig’s breakfast of Beijing’s yuan strategy.

The price of keeping the yuan stable, however, is a lack of stimulus measures for the economy. In a highly regulated and centralized economy such as China’s, lack of government-led stimulus is tantamount to an inevitable economic slowdown. China’s economy is, as we are seeing, extremely dependent on government actions and government policy maneuvers in order to achieve any sort of growth. Market forces are considerably weaker in China than they are in the United States or in Europe (even though both the Fed and the ECB are arguably far too involved in their respective economies for there to be healthy market functions taking place).

As I have commented previously, the crux of China’s economic challenge is how to restructure and reform the economy while maintaining the Chinese Communist Party’s near total grip on power.

It is somewhat facetious to say that China desperately needs economic reform. The challenges facing China’s property sector alone are a call for root-and-branch reform. Yet China is on the horns of a dilemma: how to reform the economy while maintaining the totalitarian control of the CCP? When government and economy are inextricably intertwined, how can a nation reform its economy without also reforming its government?

The data makes it painfully clear that China has multiple severe economic challenges ahead of it. The narratives, propagandistic though they may be, suggest that Beijing fully intends to do “something” about those challenges, although it is highly problematic whether Beijing understands the nature of the challenges well enough to respond productively, and it is equally problematic whether Beijing is prepared to admit the magnitude and scope of those challenges.

The decision by the PBOC to hold the line yet again on the 1-year LPR while simultaneously shrinking the M1 money supply in dramatic fashion shows that Beijing is still uncertain about “what” to do in order to stimulate the economy, while fully cognizant that “something” needs to be done. Shrinking the money supply and sustaining interest rate levels during a period of deflation are moves more calibrated to further deflate the economy rather an inflate or reflate it.

However, given the fragile state of the yuan against the dollar, there are few alternatives to these particular policy choices. China’s export-oriented economy needs at least a stable yuan, and the stimulus measures that are the typical policy response for China’s current economic woes would completely destabilize the yuan.

China’s economic dilemma is that the stimulus coin toss cannot end well—heads China’s economy deflates and possibly collapses, and tails the yuan undergoes shock devaluation which again possibly collapses the Chinese economy.

Eventually, Beijing is going to have to decide which particular economic poison it wishes to endure. Whether the CCP can endure either economic poison is a question that will only be answered once the choice of poisons has been made.

“In July last year, Chinese scholar Zhang Dandan, an associate professor at Peking University, stated in a research article that if the approximately 16 million young people who are doing nothing but mooching off their parents were considered unemployed, the actual youth unemployment rate in March last year would have been as high as 46.5 percent.”

(From today’s Epoch Times: https://www.theepochtimes.com/china/ccp-released-unemployment-rate-definitely-concerning-for-chinese-economy-experts-say-5611696?utm_source=ref_share&utm_campaign=copy)

Add THAT to China’s hopeless dilemma - 46.5% of China’s youth unemployed?

The question is whether China will have a long deflationary period like Japan had, or if China will explode into public revolutionary turmoil!

As always, Peter, I am impressed that you can succinctly make sense of convoluted data and explain it so well. “Beijing is stuck in a policy straitjacket” sums it up perfectly. China is in deep trouble and cannot win. I get the sense that all of their officials now are just trying to placate their political bosses enough mismatched policy decisions in a futile effort to keep from being blamed for the impending economic disaster. (Run!)

They are so thoroughly painted into a corner that what will be interesting now is how it affects the rest of the world. For example, I’ve read that Vancouver, BC has had, for several decades now, a large population of Chinese ex-pats. It would be interesting to see the growth rate of that