Parsing The Narratives On China: Collapse, Contraction, Or Prosperity?

Are Any Of The Narratives True?

China’s Global Times, one of the reliable media mouthpieces of the Chinese Communist Party, last week reported on a communique issued by the CCP touting the “recovery” of the Chinese economy in 2023, and the momentum the economy was building going into 2024.

China on Thursday released the statistical communique on national economic and social development in 2023, reaffirming that the Chinese economy maintained recovery momentum and made solid progress in pursuing high-quality development despite internal and external challenges.

Coming just days before China kicks off the annual two sessions, one of the most important political gathering each year, the communique, which drew a more comprehensive picture of the Chinese economy in 2023, laid a solid foundation for economic recovery in 2024 and provided valuable signals for where the Chinese economy is headed and top policy priorities for the year, analysts noted.

With the annual meeting of the National People’s Congress happening this week, such narratives are to be expected from the Chinese media. Just a few days before the Global Times paean to the Chinese economy, China Daily, another CCP media mouthpiece, touted Xi Jinping’s commitment to Chinese technology and innovation as the key to long-term security and self-sufficiency for the Middle Kingdom.

Xi, who is also general secretary of the CPC Central Committee, underlined the key role of new productive forces in underpinning China's high-quality development, stressing that sci-tech innovation is the core element for developing new productive forces.

The theory has struck a chord with the nation's legislators and political advisers as they are set to convene in Beijing next week for the upcoming annual sessions of the nation's top legislative and political advisory bodies.

Pan Jiaofeng, president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institutes of Science and Development and a deputy to the National People's Congress, said the development of new productive forces will present key opportunities to transform traditional sectors and spur the growth of emerging industries.

Xi's latest theory will serve as a short-term and long-term guideline for China to beef up innovation in science and technology and various sectors, he said.

If we take the CCP media narratives at face value (I do not recommend doing that!), then China’s economy is poised to expand by leaps and bounds.

Yet with even western media outlets prepared to tout China’s economic “strength”, how does a person parse the narratives to understand even a glimmer of what is really taking place in China?

The answer, of course, is to simply follow the data.

We should not be surprised that the CCP media outlets indulge in propaganda—one only has to read this Substack to know how prevalent propaganda is even in the West!

Yet it is also worthwhile to take note of the level of propaganda being circulated in China. Even the Washington Post would be challenged to keep up with some Chinese news outlets when it comes to generating fact free propaganda.

Beijing is countering reports of deepening structural problems and economic hardship with articles in state media about how the long-term outlook is positive as measures begin to pay off.

In the latest of such efforts, a commentary in the Chinese Communist Party mouthpiece Guangming Daily headlined “Smearing the East won’t deter its rise or prevent the downward trend of the West,” argued that although the United States’ proportion of the world’s GDP increased in 2023 as China’s shrank, it does not mean that the Chinese economic outlook is bleak or that the pattern of a “rising East and declining West” will stop.

Zhang Yongjun, deputy chief economist of the China Center for International Economic Exchanges, who wrote the commentary pointed out that China's economic growth of 5.2% last year was more than double the U.S.’s 2.5%. Furthermore, the Chinese currency’s depreciation against the dollar and falling prices versus America’s inflation and stronger currency were causal factors of a contracted GDP contribution.

However, that does not mean that Chinese propaganda cannot be found in Western publications as well. One only has to read a recent op-ed piece in Forbes to see that even the most business-centric media entities in the West can propagate propaganda.

Nowadays the vast majority of companies that defined the internet boom of the late 20th/early 21st century are gone, but not the fruits of this powerful jump into a better future. The internet defines life as we know it for the much better, and it does precisely because government didn’t step in to prop up the thousands of mediocre to bad businesses that went under in and around 2001.

It’s something to think about as U.S. economic pundits start to write post-mortems on China’s economy, while making their cases that “a China-dominated world is even less likely than it ever was.” The words in quotes are from an editorial published at the Washington Post about China’s “tanking economy.” One guesses that similar pieces were written by foreign and domestic editorialists back in 2001 about the U.S. Which is why economics writing can be a bit of an ass.

There is a particular irony in the Forbes editorial, as it suggests that there will be free-market solutions to China’s economic problems. This is an absurdity, as China is about as far removed from free market principles as can be had in the world—which is why it is possible for Xi Jinping to singlehandedly inflict enormous economic damage on the country.

It is equally absurd as it overlooks the extent to which China’s economic woes are very much an “own goal” by Xi and the CCP, having set much of the problems in motion by ham-handed policies such as Xi’s “Three Red Lines” reforms for property developers.

Yet even if we ignore such nuance, we are still challenged to consider the wisdom of the calls of even western economists for Beijing to unleash more fiscal and monetary stimulus to resuscitate the flagging economy—presuming that such stimulus is even possible in the current macro-economic climate.

Market economists also point to shorter-term factors and the lack of macro stimulus. The property policy tightening in 2020-21 and Covid-19 helped trigger the property market downturn from its unsustainable levels of construction and debt. Fiscal policy tightened in most of 2023 as local governments cut general spending and were unable to increase debt to fund investment. Weak demand exacerbated excess capacity issues, leading to declines in price and earnings, which in turn weakened corporate investment.

Both short-term macro policy support and medium-term structural policies are now needed to boost the economy and confidence. Stabilising the property market is key to restoring confidence and preventing more menacing spillover effects on the economy and financial system. Credit support to property developers will improve buyer confidence, as well as allaying defaults.

The irony becomes deliciously perverse when the same publication (the Financial TImes) argues that exact point: that massive macro stimulus is simply not an option for China any more.

Most economists agree that if it needed to, China could launch a big bazooka. The level of debt on the central government’s balance sheet is low enough for Beijing to finance a stimulus similar to the 2009 splurge that sent growth rocketing to 9.4 per cent a year.

But, with the exception of a relatively small stimulus for property, such strenuous fiscal interventions are no longer in Beijing’s preferred playbook, nor do they fit with a Xi mindset that elevates security and self-sufficiency above all, says Zongyuan Zoe Liu, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. “Beijing has been emphasising ‘high-quality growth’, which is a subtle way to acknowledge the reality of slower growth,” she says. “It is unlikely to do debt-fuelled stimulus, which would exacerbate the structural imbalances, impair China’s credit rating outlook and constrain long-term growth.”

Indeed, that 2009-10 stimulus is still blamed in Beijing policy circles as a root cause of the current slowdown. The flood of cheap liquidity contributed to the continuing local government debt crisis, nurtured a network of underground banks, inflated property prices to unsustainable levels and spurred overcapacity in a host of industrial sectors.

Simply put, the contrarian view to the call for massive stimulus by Beijing is the argument that prior rounds of massive stimulus by Beijing have resulted in such an accumulation of government debt as well as fueling unparalleled asset bubbles that any new round of massive stimulus carries an outsized risk of destabilizing and destroying what remains of the Chinese economy.

Indeed, it is difficult to see where Beijing could benefit from either fiscal or monetary stimulus at this point.

While exports are still in a multi-year downward trend, over the past few months they have seen some increase—which may indicate that at least some “recovery” is in the offing.

The challenge will be if China’s need for exports will be hampered by the larger global economic contraction currently unfolding.

It will be especially challenging if China’s imports continue to decline as they have been since the end of 2021 just as with exports.

Without fresh inputs, there is a finite amount of increase feasible in China’s export capacities. Without imports there are no inputs to manufacture goods for export.

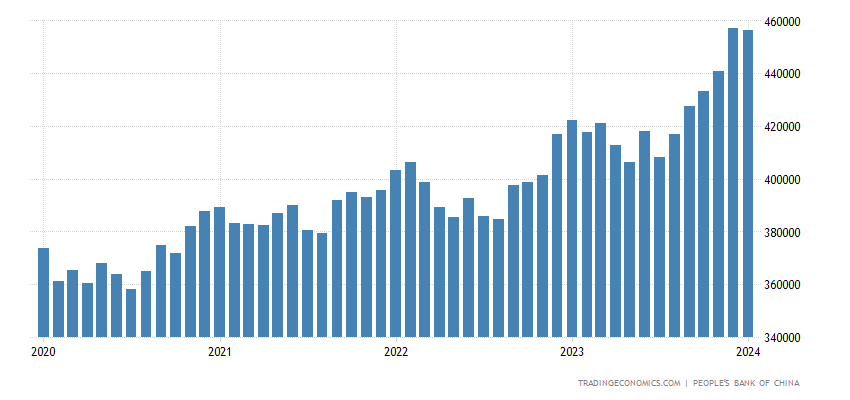

A strategy of stimulus is similarly hampered by the extent to which the PBoC has expanded its balance sheet in prior stimulus rounds.

As we have seen even with the Fed’s own monetary policies, there is a limit to how much debt any central bank can accumulate without impairing the functioning of said central bank.

In truth, just about any form of government stimulus or policy micromanagement by government is a bad idea.

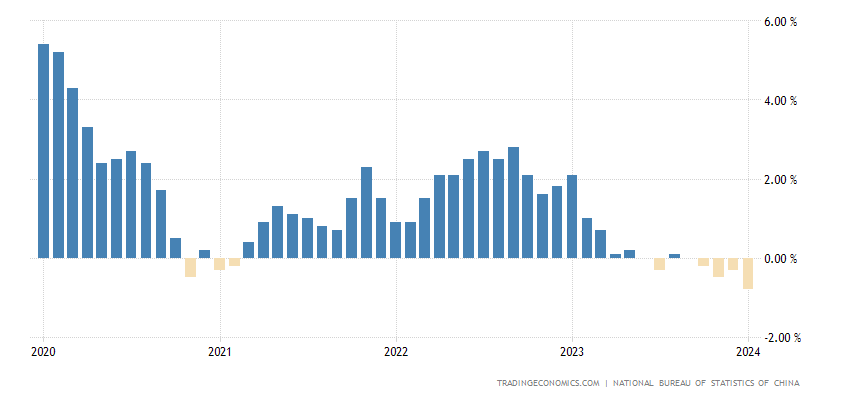

That stimulus is simply not an option for China is driven home by their growing problem of producer price deflation perpetuating a downward spiral for prices.

Yet at the same time, that China’s economy is already suffering from deflation in key areas is on any other day would be a good argument on its own for some level of stimulus. A major reason why China is experiencing deflation is that, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, manufacturing activity has been declining for ten of the past eleven months, and would have declined persistently throughout that period but for a single month of marginal expansion last September.

Indeed, one of the phenomenal challenges facing Beijing is that, despite a decade of loose and getting looser monetary policy, China is facing not persistent inflation but persistent deflation, with inflationary pressures getting steadily weaker since 2020.

Loose monetary policies are a powerful inflationary force, not a deflationary one. Yet China is grappling with deflation, and is unable to generate any meaningful inflation within its economy. That China is experiencing anything besides hyperinflation more serious than what has recently occurred here in the United States, given the length and looseness of its money policies, alone highlights the magnitude of China’s economic collapse.

If monetary policy cannot produce inflation, monetary stimulus cannot work, as inflation is what makes monetary stimulus effective.

The challenge when reading the diverse narratives on China’s economy is that many, perhaps even all, have at least some grains of truth.

China’s previous economic recovery playbook has involved massive macro stimulus, and so it is rational that some would call for a repeat of those measures. However, it is also true that because of those previous rounds of stimulus, China has saddled itself with so much debt it no longer has room on the PBoC balance sheet for stimulus debt.

It is also true that Xi Jinping’s “three red lines” targeted the worst abuse by property development companies—that of spending the monies received from home pre-sales on things other than the building projects, resulting in the accumulation of massive debts while bleeding away the capital necessary for those projects. Yet it was government rigidity and inflexibility in enforcing the “three red lines” that catalyzed the debt crises that destroyed Evergrande and threaten to destroy Country Garden.

And it is equally true that the stimulus efforts within western economies—and in the United States in particular—have not been a smashing success either, as readers of this Substack will know full well.

It is impossible for a country of 1.3 billion people and an established industrial base not to have significant economic potential. If the economic potential of each of those 1.3 billion people could be leveraged to the fullest, China’s economy would easily dwarf that of the United States, and by several orders of magnitude. That much is little more than simple math.

China’s dilemma is that it quite obviously is not leveraging the economic potential of each of its 1.3 billion people to the fullest, and its structural issues and challenges are such that it is finding it increasingly difficult to leverage even that portion of its economic potential that is has been thus far.

It is somewhat facetious to say that China desperately needs economic reform. The challenges facing China’s property sector alone are a call for root-and-branch reform. Yet China is on the horns of a dilemma: how to reform the economy while maintaining the totalitarian control of the CCP? When government and economy are inextricably intertwined, how can a nation reform its economy without also reforming its government?

The data makes it painfully clear that China has multiple severe economic challenges ahead of it. The narratives, propagandistic though they may be, suggest that Beijing fully intends to do “something” about those challenges, although it is highly problematic whether Beijing understands the nature of the challenges well enough to respond productively, and it is equally problematic whether Beijing is prepared to admit the magnitude and scope of those challenges.

Based on the current data, China’s economy is in a downward spiral of collapse. It will take much more than technology and innovation to pull the country out of that spiral. Only time will tell if the upcoming annual sessions of the National People’s Congress will provide what China needs.

“Most economists agree that if it needed to, China could launch a big bazooka.” Is an interesting choice of words. The question is will China’s economic condition make it more or less likely to lead her to war. It can be argued both ways.

I’ve been reading quite a few media deep-dives on China in recent months, and yours, Peter, are always the best on every metric I can think of - hard data, comprehensiveness, insightful analysis and conclusions, wise interpretations, etc. You are not misled by anything, whether it’s propaganda, fudged data, or superficial coverage by reporters. You are just the best, so thank you once again!

The Forbes editorial surprised me - are they really that superficially informed and naive about China’s culture and economy? It makes me think that their editorial was a paid piece by someone with interests in propping up China, or some similar explanation. Did you have that suspicion as well?