China's Main Economic Weakness: Xi Jinping

China's Woes Are Mainly Due To Xi Jinping's and the CCP's Own Mis-Steps

The elemental conceit in all authoritarian systems is that those with power know how to use it “properly”. We want to believe that people rule ultimately for the good of everyone.

But—what if those in charge are not acting for the good of all? How can we tell, and what do we do about it?

We must ask these questions of China in particular, given the ways in which their economy appears to be unraveling.

Is Xi Jinping doing the right things for the right reasons in China? Does he even know what he is doing? Does the CCP?

The data makes a compelling case that neither Xi nor the CCP know what they are doing—or simply don’t care, which would be even worse.

To assess how Xi and the CCP have contributed to China’s current economic problems, we need to gain some perspective on how those problems came to be.

A intriguing—and plausible—thesis the origins of China’s current deflation and Xi Jinping’s role in it comes from economist Kenneth Rogoff, who asserts that China’s current economic woes are the delayed reactions to the “debt supercycle”. Essentially, in this model, China’s blast of debt-fueled stimulus after the Great Financial Crisis is what has brought China’s economy to this point.

China’s current problems can be traced back to its massive post-2008 investment stimulus, a significant portion of which fueled the real-estate construction boom. After years of building housing and offices at breakneck speed, the bloated property sector — which accounts for 23% of the country’s GDP (26% counting imports) – is now yielding diminishing returns. This comes as little surprise, as China’s housing stock and infrastructure rival that of many advanced economies while its per capita income remains comparatively low.

Certainly there is reason to consider this thesis, as China has made significant use of debt stimulus over the past decade and a half, nearly doubling its debt-to-GDP ratio in that time, based on Bank of International Settlements data.

Viewed against this timeline, it is clear at least part of this debt burden came before Xi Jinping’s presidency. At a minimum, his predecessor, Hu Jintao, must bear some responsibility for this.

Still, since moving into the top spot in 2012, Xi Jinping has not done much if anything to curtail China’s indebtedness. Quite the contrary, the steady rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio shows that Xi Jinping has been even more reliant on debt to stimulate the economy than his predecessors.

Additionally, Xi has maintained a steady growth of the money supply in a manner very reminiscent of “quantitative easing” here in the United States throughout his time in office.

A principal argument to be made for China being mired in deflation now is that, despite such a steady growth of the money supply, China is not experiencing high rates of consumer price inflation.

Moreover, it is against this backdrop of rising indebtedness and money supply growth that we have to consider policies such as Xi Jinping’s “Three Red Lines” from 2020:

In an effort to stave off a broader banking crisis spurred by a growing wave of mortgage defaults (the inevitable consequence of refusing to make payments), the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission has asked lenders to extend still more credit to embattled developers, in order to facilitate completion of housing projects and thus halt the boycott wave.

China’s banking regulator has asked lenders to provide credit to eligible developers so they can complete unfinished residential properties after home buyers stopped paying mortgages on at least 100 projects across 50 cities.

There is no small irony in Beijing making this move, as the developer crisis was catalyzed by the introduction in August of 2020 of the “Three Red Lines”, a set of financial metrics meant to curb debt growth among real estate developers.

Three Red Lines Criteria:

Liability to asset ratio of less than 70% (excl. advanced receipts)

Net gearing ratio of less than 100%

Cash to short-term debt ratio of at least 1

If all three criteria are passed (green), the company can increase its debt up to 15%. A breach of one (orange), two (yellow), and three (red) criteria will decrease the percentage to which debt can grow to 10%, 5%, and 0% in the following year respectively.

The problem the “Three Red Lines” revealed was that a sizeable number of developers violated at least one of the metrics, and large but highly indebted developers such as Evergrande were in violation of all three, as was noted shortly after the imposition of the new metrics.

Evergrande’s problems, and later Country Gardens, began when implementation of the “Three Red Lines” policy forced developers to deleverage rapidly, thereby exposing how much their business model was addicted to debt. To borrow a line from Warren Buffett, thanks to the Three Red Lines the tide went out on Chinese developers and they were all found to be swimming naked.

Ultimately, Xi would be forced to retreat from the Three Red Lines policy in order to stabilize China’s real estate markets—an effort that appears to have largely been made in vain. Still, by the time he did, the damage had been done, and the real estate bubble had begun to burst.

Nor were the “Three Red Lines” Xi’s only policy overreach. There was also his 2021 crackdown on China’s technology sector.

Even if he’s not pursuing a new Cultural Revolution, Xi is rewriting China’s social contract. Since 1978, China has been living with an awkward compromise between Marxist ideology and an increasingly market-driven economy. Xi knows that his China dream of national rejuvenation needs growth, which increasingly has to come from innovation and productivity, something the market delivers better than China’s state-owned enterprises.

Yet it is clear this market will be different from before. Xi’s first economic program in 2013 stated that “the market should determine the allocation of production resources” but also that “the main responsibility and role of the government is to maintain the stability of the macroeconomy…and intervene in situations where market failure occurs.” But that intervention risks undercutting the entrepreneurial energy that propelled China’s tech sector to its recent apex.

The most dramatic step was the first step, when Beijing deralied the projected $37 Billion IPO over Jack Ma’s Ant Group in November of 2020.

One year ago, on Nov. 3, 2020, China’s regulators pulled the plug on what was supposed to become the largest IPO of all time: Ant Group, valued at U.S.$37 billion back then. The regulatory storm in the year that followed has cost investors in China’s internet companies a fortune, triggered a debate over whether China was still investable, and even whether it is undergoing a new “Cultural Revolution.”

In March of 2021, tech conglomerate Tencent became the next target for increased supervision.

China’s top financial regulators see Tencent as the next target for increased supervision after the clamp down on Jack Ma’s Ant Group Co., according to people with knowledge of their thinking. Like Ant, Tencent will probably be required to establish a financial holding company to include its banking, insurance and payments services, said one of the people, seeking anonymity as the discussions are private.

The two firms will set a precedent for other fintech players on complying with tougher regulations, the people added.

Then there was the rather brutal treatment of Didi, the Chinese ride-sharing firm whose previous claim to fame was having driven Uber out of China.

The ride-hailing giant shed $70 billion of market value at one point after regulators suspended its apps from stores, imposed curbs on overseas listings and tightened up on Didi’s industry in the wake of its June 2021 IPO. The company, once feted as the national champion that drove Uber Technologies Inc. out of China, has since come to symbolize the extent to which Beijing is willing to go to curb the power and influence of its most successful internet corporations.

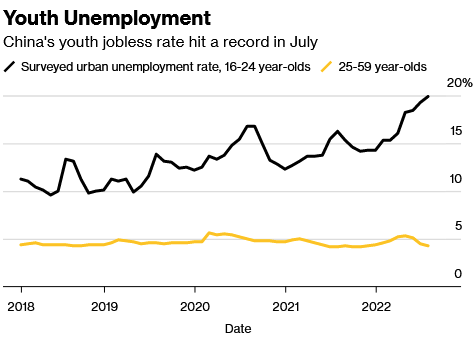

While Xi and the CCP succeeded in bringing much of the tech sector back firmly within party control, the tech crackdown also coincides with a rise in youth unemployment in China.

Rocked by a series of punishing regulations that froze deal-making and wiped out the once-swaggering industry’s growth, sector leaders from Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. to Tencent Holdings Ltd. and Xiaomi Corp. this year began firing people by the thousands.

Those cutbacks foreshadow a more fundamental shift in the giant industry’s traditional role as the largest and most sought-after employer, with potentially grave consequences. A record of almost 11 million new graduates are expected to flood the labor market this year. With the tech sector no longer offering them as lucrative and exciting a career path as it once did, many will join the jobless ranks in an economy where one in five people between the ages of 16 and 24 are already out of work.

The onset of the COVID pandemic largely catalyzed job loss among young people, but Beijing’s regulatory crackdown on tech served to pour a bit of gasoline on what was already a growing problem.

With China’s youth unemployment data for July so bad Beijing has opted not to release them, it is essential to understand that much of that unemployment data can easily be laid at Xi Jinping’s feet, because of either Xi’s tech sector crackdowns or the “Zero COVID” lockdown protocols.

It was apparent last spring in the hellscape that was Shanghai under a Zero COVID lockdown that there would be a ginormous price tag for Xi’s lockdown policies. We now can see that at least some of that price tag is being paid by China’s unemployed youth.

The data quite clearly shows that China’s youth unemployment problems have been made considerably worse by Xi’s Zero COVID lockdown protocols.

At a minimum, Zero COVID has reduced the number of jobs available for new entrants to the workforce.

Covid restrictions were stifling, and employment opportunities were grim. She is set to graduate next year with a degree in tourism management and has submitted more than 80 applications for jobs. She has not received a single offer.

Many young people had followed what the Chinese Communist Party told them to do, only to be left disillusioned, Ms. Liu said. “What we are seeing is that people are struggling to survive.”

That discontent bubbled over in recent weeks as throngs of students, job seekers and young professionals stormed the streets in major cities across China to protest the government’s iron-fisted Covid rules. The unrest brought into view the party’s longstanding concern that a shortage of jobs and economic opportunities for young people posed a threat to social stability.

On Wednesday, Beijing caved to the protesters’ demands and relaxed many of its “zero Covid” restrictions. But the bigger and more vexing problem remains: An ugly job market with too many applicants jostling for too few jobs could mean that China’s decades of economic prosperity may soon be out of reach for many young people.

Between the destruction of job opportunities and other economic privations, by last November Xi’s Zero COVID measures had pushed the Chinese people too far, triggering widespread protests against the lockdowns. As a result, Xi was forced to abandon Zero COVID last December.

When we accept Rogoff’s contention that the seeds for China’s current problems were sown all the way back in the GFC aftermath, we must also accept that Xi Jinping and the CCP in general have done quite a bit to exacerbate and accelerate the situation. Xi’s totalitarian rule over China has taken a bad situation and made it worse by multiple orders of magnitude.

Yet the spectre of Xi Jinping does not merely hang over China’s recent economic history. Xi Jinping’s administrators at the People’s Bank of China have also been back-footed in dealing with China’s failure to “rebound” from the end of Zero COVID. Their most recent arguably inadequate move: trim the 1-year loan prime rate while leaving the 5-year rate intact.

The PBOC left its five-year loan prime rate — the peg for most mortgages — unchanged at 4.2%, while economists expected a 15 basis point cut due to default risks from festering liquidity woes in the country’s property sector. Country Garden is on the verge of default, while Evergrande filed last week for bankruptcy protection in a Manhattan court.

“The underwhelming LPR announcement strengthens our view that the PBOC is unlikely to embrace the much larger rates cuts that would be required to revive credit demand,” Julian Evans-Pritchard, Capital Economics’ head of China, wrote in a note.

“Hopes for a stimulus-led turnaround in economic activity largely depend on the prospect of greater fiscal support,” he added.

The argument by economists and financial analysts is that the PBOC needs to make much bigger moves than this.

Julian Evans-Pritchard and Zichun Huang, economists at the consultancy Capital Economics, said China was trying to balance efforts to stimulate the economy with concerns about the health of its banks.

“The big picture is that the PBoC’s approach to monetary policy is of limited use in the current environment and won’t be enough, on its own at least, to put a floor beneath growth,” they wrote. “Reviving demand would take much larger rate cuts, or regulatory measures to effectively restore confidence in the housing market.”

Instead of making big rate cuts or major regulatory changes, however, Xi Jinping and the CCP have been playing an economic version of “small ball”, relying on jawboning bank executives into making more loans to deliver monetary stimulus without direct involvement by Beijing.

China’s central bank and financial regulators met with bank executives and told lenders to boost loans to support a recovery, adding to signs of heightened concern from policymakers about the deteriorating economic outlook.

Officials from China Life Insurance Co. and stock exchanges were also at the same meeting on Friday, where authorities discussed measures with the financial sector in preventing and reducing local government debt risks, according to a statement from the central bank on Sunday.

These measures are merely the recent incrementalist responses Xi’s government has made to these rapidly expanding problems.

Somewhat equally surprising has been Beijing’s response to this perfect storm of debt issues. Rather than executing a strong and significant intervention to head off these growing issues and prevent contagion, Beijing has been consistently reactive and even hesitant in its response.

Last month, China’s state banks offered a series of 25-year loans to heavily indebted LGFVs at low or no interest to alleviate some of their debt burden.

Last month, the National Development and Reform Commission issued a “plan” to “restore and expand” domestic consumption—a plan that was long on policy pronouncements and short on details.

The NDRC went on to issue more policy statements voicing support for private enterprise within the Chinese economy.

The Chinese Politburo hinted at relaxation of real estate purchase restrictions in several major Chinese cities during the second have of 2023.

China’s National Financial Regulatory Administration, Beijing’s banking regulator, set up a task force to investigate debt and risk issues at Zhongrong Trust.

The People’s Bank of China recently issued a surprise 15bps cut on their one-year medium-term lending facility, lowering the rate from 2.65% to 2.5%. This was the second rate reduction in three months.

On top of the rate cut, the PBOC also injected 297 billion yuan into financial markets through the bank’s repo mechanisms.

China’s State Council promised more “targeted and forceful” macroeconomic controls to boost domestic consumption and meet Beijing’s annual economic growth targets.

While these measures may add up to substantial intervention at some point, by being rolled out in incrementalist fashion, they never deliver enough impact to alter the economic dynamics at play. Worse still, they show Beijing being merely reactive, enacting policy only after the emergence of some new negative data. Such reactivity is the worst of all possible stances, for there is no strategic cohesion to the reactions, nor is there the liberating effect to be had from standing aside and letting 1.3 billion Chinese sort out their personal economic circumstances to their own benefit. In order to realize any benefit at all from central planning of an economy there needs to be some actual planning, and what has emerged from Beijing thus far does not show that there is any planning taking place.

Paradoxically , while Xi pursues a passive, reactive economic strategy at home, abroad there are indications that his “wolf warrior” diplomats are still around, pushing a more aggressive economic posture internationally. At the ongoing BRICS summit in Johannesburg, South Africa, Chinese diplomats are advocating the BRICS group of nations work to establish economic rivalry with the G7/G20 groups of nations.

China will push the Brics bloc of emerging markets to become a full-scale rival to the G7 this week, as leaders from across the developing world gather to debate the forum’s biggest expansion in more than a decade.

Economic warfare is hardly the sort of foreign policy that is likely to result in restored economic growth and health. Yet it is increasingly the manner of foreign policy being embraced by Xi Jinping and the CCP. At a time when they need to increase exports and foster favorable trading relationships globally, they are choosing to be adversarial, raising geopolitical and economic tensions rather than reducing them. They are hardly the only country choosing to do this, but, given the parlous state of the Chinese economy and its heavy reliance on exports, they arguably have the most to lose and the least to gain from playing this particular geopolitical game.

This combination of continued confrontation in the geopolitical sphere and reactive, incrementalist monetary and fiscal policies argue against China’s leadership having a good grasp of the severity of their economic challenges. In just about every dimension, there exists an argument that, from Xi Jinping on down, Beijing just “doesn’t get it”.

Xi clearly failed to appreciate the economic ramifications of his “Three Red Lines” policy, which has triggered serial debt crises among China’s property developers.

Xi clearly failed to appreciate the extreme dislocations and stresses “Zero COVID” would impose on the country.

Arguably, Xi fails to appreciate that, if Beijing is going to continue to attempt to impose its will on the Chinese economy, Beijing needs to do more than just be reactive to the latest batch of economic bad news. Half measures are frequently worse than no measures at all.

Alternatively, if one wants to argue that the ending of Zero COVID and the abandonment of the “Three Red Lines” means that Xi has finally “seen the light” at least a little bit, Beijing has yet to articulate any strategy to contend with the fallout from these policies. The “Three Red Lines” helped precipitate the bursting of China’s real estate bubble, and Zero COVID completely roiled the economy, yet Beijing is making no real effort to clean up either of these messes.

At every significant milestone on the path to China’s current mix of economic dilemmas, we see Xi Jinping and the whole of the Chinese Communist Party influencing and directing economic outcomes. Far more than can be plausibly said to be the case in the US, Xi Jinping and his selected team of bureaucrats and administrators intervene directly in the Chinese economy almost on a daily basis. Unlike in the US, Xi Jinping does not have even a pale version of the electoral modes of accountability that the President of the United States and the Congress notionally do.

China’s subpar economic performance and subpar economic prospects are blunt testimonies to why such authoritarianism is a bad idea, why centralized government authority in the end must fail: no one is ever that good of an “expert”, and frequently those who presume to be the “experts” have the least expertise.

No good ever comes from having one man in charge of a country. China’s ongoing deflation proves that truism yet again in spades.

I know you and I disagree on this point, but Xi doesn't care about regular economic metrics and only about world domination. With the damage inflicted on the US by Russia, Ukraine, China itself, Biden, and Trump's exclusion, China looks set to rise to the top of what? The planet, that's what, at least until they have it out with Russia.

Xinnie the Pooh is a willy-nilly, silly old dictator.