Is Beijing Losing Control Of China's Collapsing Real Estate Sector?

Mortgage Boycotts Are Forcing Developer Bailouts

Last week I explored the potential for China’s metastasizing real estate developer crises to trigger a larger systemic banking crisis.

Events since are beginning to answer the question in the affirmative: Beijing is increasingly caught between a developer rock and a homebuyer hard place, and is once again being driven by events rather than asserting any semblance of control. A larger systemic crisis, while not as yet acknowledged, appears very much to be underway.

Crisis Not Contained

One key sign that events are moving faster than Beijing’s policies was the sudden (yet wholly unsurprising) suppressing of online “crowd-sourced” documents adding up the number of homebuyers that are protesting lengthy delays in completion of pre-sold homes by withholding mortgage payments.

Shared files managed on platforms including China’s Quora-equivalent Zhihu Inc. and on sites like Kdocs and Wolai have been banned following reports that the number of homebuyers refusing to pay mortgages surged in a span of days. GitHub, a popular file-sharing site for coders, remains as a source for people to post documents.

By targeting these documents, Beijing is apparently working to conceal the actual magnitude of the mortgage protest movement—as well as the movement’s rapid growth.

Yet while Beijing seeks to suppress this information, it is unable to simply ignore the mortgage protests, as the unpaid mortgages are adding to banks’ bad debts, threatening the stability of the banking sector overall.

Lenders have said the bad housing loans are controllable. But the spike in incidents is fueling concerns that the property troubles -- which have largely centered on developers following a government crackdown on excess leverage -- will engulf big banks and China’s middle class, who have an estimated 70% of wealth stored in real estate.

“This is a political protest,” Diana Choyleva, chief economist at Enodo Economics, said in an interview on Bloomberg Television. “It’s not going to be a banking crisis, they are not there. But it a crisis potentially of confidence and one that the Chinese Communist Party fears tremendously.”

Despite assurances that mortgage defaults as well as developer liquidity concerns are under control, the spread of the boycotts is also reflecting the growing problem of developers not being able to complete already-sold housing projects.

Private gauges are more alarming. Guangfa Securities analysts estimate about 5% of projects measured by floor area have stalled, translating to roughly 2 trillion yuan, about $300 billion, in mortgages, or 1% of total bank loans as of June. It is a substantial step up to the existing non-performing loan ratio at 1.8%. That damage assessment is probably conservative too considering some buyers borrowed for down payments and it is early days in the crisis.

The challenge for China’s banking and real estate regulators is that any regulatory response to the mortgage boycotts further constrains already tight developer liquidity, which would threaten still more housing project delays, which in turn could catalyze additional boycotts and mortgage defaults.

The wave of Chinese homebuyers not paying mortgages on stalled projects will add pressure to developers’ liquidity by weakening presales and restricting use of customers’ down payments, said Nomura International Hong Kong Ltd.

The refusals to pay will “likely drive stricter control over presales escrow accounts and hurt sales demand further,” credit desk analyst Iris Chen said in a note Thursday. “Mortgage issuance may also face a stricter approval process that will slow down cash collection.”

The mortgage boycotts are thus feeding into the developer crisis to create what could turn into a true “death spiral” for Chinese real estate.

The Solution: Bailouts And Forgiveness For All

In an effort to stave off a broader banking crisis spurred by a growing wave of mortgage defaults (the inevitable consequence of refusing to make payments), the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission has asked lenders to extend still more credit to embattled developers, in order to facilitate completion of housing projects and thus halt the boycott wave.

China’s banking regulator has asked lenders to provide credit to eligible developers so they can complete unfinished residential properties after home buyers stopped paying mortgages on at least 100 projects across 50 cities.

There is no small irony in Beijing making this move, as the developer crisis was catalyzed by the introduction in August of 2020 of the “Three Red Lines”, a set of financial metrics meant to curb debt growth among real estate developers.

Three Red Lines Criteria:

Liability to asset ratio of less than 70% (excl. advanced receipts)

Net gearing ratio of less than 100%

Cash to short-term debt ratio of at least 1

If all three criteria are passed (green), the company can increase its debt up to 15%. A breach of one (orange), two (yellow), and three (red) criteria will decrease the percentage to which debt can grow to 10%, 5%, and 0% in the following year respectively.

The problem the “Three Red Lines” revealed was that a sizeable number of developers violated at least one of the metrics, and large but highly indebted developers such as Evergrande were in violation of all three, as was noted shortly after the imposition of the new metrics.

Among the major players, Evergrande and Guangzhou R&F Properties fall short on all three metrics and face the most pressure to cut debt quickly. They may need to cut borrowing by 19 and 21 percentage points, respectively, under the new rule, based on their 2019 finances.

Sunac China Holdings, which meets only one metric, may need to pare back debt by 35 percentage points. Among China's 189 listed developers, 14 were in breach of the three red lines as at early this month.

Among the biggest by market capitalisation were Zhongtian Financial Group, Oceanwide and LVGEM China Real Estate Investment.

By advocating for more debt for developers, Beijing has effectively retreated from this policy and has begun bailing out property developers in a bid to salvage the sector.

At the same time, Beijing is contemplating extending a “grace period” to homeowners, so that their mortgages will not automatically fall into default as a result of intentional non-payment. In effect, Beijing is proposing to allow the boycotts to continue, potentially creating a new moral hazard in real estate, as there is the risk such forgiveness will encourage still more boycotts.

While a payment holiday could backfire if it encourages owners of completed properties to also protest for relief after home prices slumped, regulators are calculating the move is necessary to inject confidence into the market and buy time for developers to complete projects. Homeowner eligibility and the length of grace periods will be decided by local governments and banks, the people said.

To bolster China’s “village banks”, many of whom carry significant exposure to the mortgage boycotts, Beijing is working to shore up capital at these smaller banks.

To address rising public anger over frozen deposits at some rural banks in the country, the regulator on Sunday pledged to boost capital buffers for thousands of small banks, which are facing worsening balance sheets amid a weak economy and a slump in property market.

This bank bailout is being accomplished through special bonds authorized by Beijing and issued by local and regional governments.

To strengthen the capital of small and medium-sized banks, a combined quota of 103 billion yuan of special local government bond issuances was granted to the provinces of Liaoning, Gansu and Henan and the northern port city of Dalian in the first half of 2022, according to the newspaper.

In the near future, other local special bond issuance plans will be approved, and it is expected that the overall amount of 320 billion yuan will be distributed by the end of August, the newspaper added.

Beijing may also be moving towards a massive full-bore government bailout of real estate, in a move highly reminiscent of the US Government’s bailout of the banking sector during the 2008 Great Financial Crisis. Certainly China’s banks would welcome such a program.

Monetary easing alone cannot provide a quick fix to property sector problems, Xu Gao, chief economist at Bank of China International told local media. He floated the idea of a 1 trillion yuan ($148 billion) relief fund to buy non-controlling equity stakes in troubled developers. Once the builders are adequately capitalized with state-backed money, banks will be more willing to lend and the public will feel more assured of their new home purchases.

Depending on how one views certain remarks by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang during his annual work report in March, "TARP with Chinese characteristics” may already be in the works.

China plans to set up a financial stability fund and adopt measures to keep housing prices stable, as policy makers ramp up efforts to prevent systemic risks.

“A fund for ensuring financial stability will be established, and market- and law-based ways will be used to defuse risks and potential dangers,” Premier Li Keqiang said in his annual work report, without giving more details.

Markets Remain Unconvinced

China’s stock markets have had an uneven and mixed response to these moves. After having been on a downward trend in recent days—largely because of earnings woes at China’s banks and exposure to the real estate sector—stock indices reversed up after the announcements on Monday (July 18), only to trend down again on Tuesday.

Financial company shares, which have struggled throughout the second quarter and have been down sharply to start July, however, have so far staged a modest rebound since the government support efforts were announced.

Beijing has significant heavy lifting still to do before there is a clear market signal of confidence that the measures taken will turn out well. Very likely additional support for both banks and property developers will be required—and will most likely be forthcoming. Thus far nothing announced is likely to reverse the recent declines in new home prices—and won’t unless Premier Li’s “financial stability fund” becomes a reality.

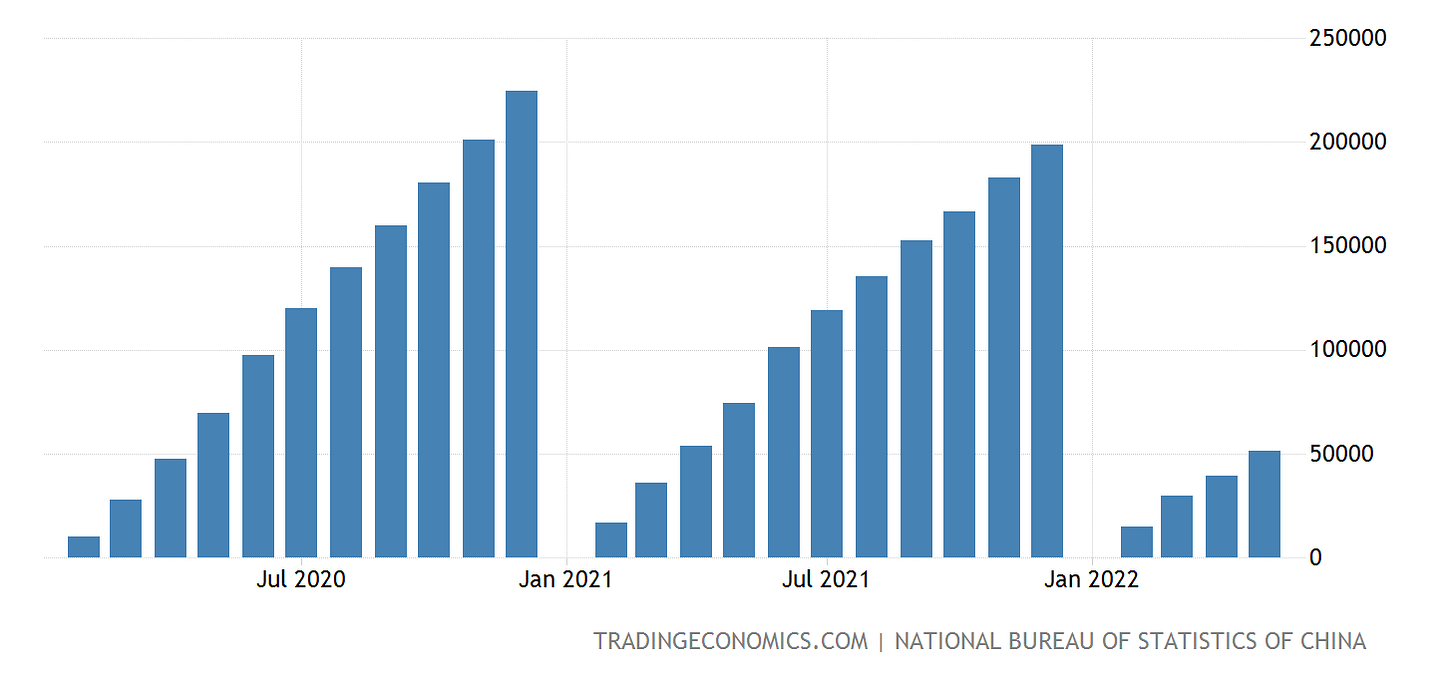

Beijing’s support measures also seem unlikely to reignite the pace of construction, which in May was little more than half of what it was a year ago.

The net effect of the bailouts thus far for both banks and real estate developers, coupled with the prospect of a broad “amnesty” for homeowners who cease making payments on their mortgages, has been to at most slow the ongoing collapse of the real estate sector and its inevitable stresses on China’s banks. Stopping that collapse is likely to require the more massive intervention Li teasingly hinted at in March.

The Core Problem: The Money Is Gone

In one key aspect, the current real estate woes in China do bear a certain resemblance to the 2008 financial crisis here in the US: the money is gone.

In 2008, homeowners, placed in financial straits by rising interest rates on mortgages and declining home prices, were unable to service their mortgages and began to default at an accelerated pace, which in turn catalyzed the drop in market value for a variety of mortgage-backed securities and a variety of derivative products built upon those mortgages.1 Homeowners and investors alike simply ran out of money.

In China today, it is the developers that are running out of money, before the homes they have pre-sold and committed to build are finished. This in turn is prompting the mortgage boycott, as homeowners rebel at the prospect of seeing their housing down payments vanish without a home to show for them. At the same time, developer defaults are adding to banks non-performing loans—which is toxic to any bank’s lending activity. Homeowners defaulting on their mortgages as a result of refusing to pay on them is exacerbating this problem. The developer liquidity problems are thus fueling a “contagion” effect, causing the real estate crisis to evolve into a systemic banking crisis as well.

Should China allow its real estate bubble to continue deflating without state intervention, the result will at a minimum be a broader mortgage boycott/homeowner rebellion. Further bank runs as were seen in Henan province earlier this year are also a likely consequence. Neither circumstance does much for the social stability President Xi Jinping needs in the run-up to this fall’s National Congress of the Communist Party.

If property developers are left to resolve their financial problems on their own, housing starts will likely continue to weaken. A growing uncertainty that pre-sold homes will actually be completed will have a continued depressive effect on housing prices—and that is the larger land mine within these unfolding crises: 70% of household wealth among China’s nascent middle class is tied up in housing. The wealth destruction effect of the bursting property bubble will be felt most keenly among homeowners, not among China’s investor class.

While the long-term economic resolution would be to allow the property bubble to fully deflate, and let the network effects of a crashing real estate sector work through the rest of the economy, allowing the economy to achieve a stable foundation in the end, the political consequences of such a “do nothing” approach are almost certainly more than the CCP is prepared to accept. The mere fact that the mortgage boycotts are likely to result in a measure of debt amnesty is testament to the CCP’s low tolerance for social instability. Allowing 70% of the average Chinese citizen’s wealth to evaporate can only fuel that instability.

To avoid that instability, Beijing is compelled to “something”. To prop up the real estate sector, insolvent developers must either be supported or suitable mergers with stronger firms must be arranged (which would be another parallel to events here in the US during the 2008 crisis). Ultimately, a larger rescue/bailout of property developers is all but inevitable.

Yet such a rescue eliminates what little credibility remains in the “Three Red Lines” imposed on developers in 2020. To stave off a broader systemic crisis, Beijing is being forced to back off from efforts to rein in developer debt—and indeed is likely to encourage developers to take on further debt, just to ensure housing projects are completed.

Despite its many assurances to the contrary, Beijing is being forced into a progressively narrower range of options, none of which align with previous domestic policy goals. While the situation in China lacks the media coverage the 2008 financial crisis had here in the US, China now—like the US then—is approaching a point of economic and regulatory singularity—a systemic crisis so far-reaching the ultimate consequences are simply incalculable.

When consequences are incalculable, it is foolish to prognosticate on what consequences will ultimately arise from whatever policy responses Beijing implements. However, it is not prognostication to recognize that there will be consequences, and that the reality of those consequences is that Beijing is losing even nominal control over the Chinese economy.

The next few years in China are promising to be the most “interesting” of times—for everyone.

This is a very generalized view of the 2008 financial crisis and ensuing recession, the particulars of which are still a matter of considerable debate. While a full exploration of that recession is beyond the scope of this article, the key element here is the mortgage default rate, which in every analysis is near the nexus of the financial disruptions in that event.

A China "TARP" and it couldn't happen to a nicer set of leaders.

The real question, Peter, is how much will this cost the US taxpayer?

If the Feds could just 'seize' the pension funds, 401s, and everything else, even the equity in our paid for homes or our not yet paid for homes, 'deem' us a UBI at retirement age, they could kick the worldwide PONZI scheme down the road for what, another 4 to 5 years?

For today: 👉(finger pointing right at Chiii-na) 😂🤣😂🤣😂🤣 Couldn't happen to a better communist!